Leadership and Self-Deception was the introduction. The Anatomy of Peace goes beyond, deepening the solutions and extending the ideas to all aspects of life. Just two weeks after the “March Meltdown” described in Leadership and Self-Deception, Lou and Carol Herbert enroll their son, Cory, in a treatment program and there encounter ideas and people that change them forever. Read the first two chapters of The Anatomy of Peace.

“I’m not going!” The teenage girl’s shriek pulled everyone’s attention to her. “You can’t make me go!”

The woman she was yelling at attempted a reply. “Jenny, listen to me.”

“I’m not going!” Jenny screamed. “I don’t care what you say. I won’t!”

At this, the girl turned and faced a middle-aged man who seemed torn between taking her into his arms and slinking away unnoticed. “Daddy, please!” she bawled.

Lou Herbert, who was watching the scene from across the parking lot, knew before Jenny spoke that this was her father. He could see himself in the man. He recognized the ambivalence he felt toward his own child, eighteen-year-old Cory, who was standing stiffly at his side.

Cory had recently spent a year in prison for a drug conviction. Less than three months after his release, he was arrested for stealing a thousand dollars’ worth of prescription painkillers, bringing more shame upon himself and, Lou thought, the family. This treatment program better do something to shape Cory up, Lou said to himself. He looked back at Jenny and her father, whom she was now clutching in desperation. Lou was glad Cory had been sent here by court order. It meant that a stunt like Jenny’s would earn Cory another stint in jail. Lou was pretty sure their morning would pass without incident.

“Lou, over here.”

Carol, Lou’s wife, was motioning for him to join her. He tugged at Cory’s arm. “Come on, your mom wants us.”

“Lou, this is Yusuf al-Falah,” she said, introducing the man standing next to her. “Mr. al-Falah’s the one who’s been helping us get everything arranged for Cory.”

“Of course,” Lou said, forcing a smile.

Yusuf al-Falah was the Arab half of an odd partnership in the Arizona desert. An immigrant from Jerusalem by way of Jordan in the 1960s, he came to the United States to further his education and ended up staying, eventually becoming a professor of education at Arizona State University. In the summer of 1978, he befriended a young and bitter Israeli man, Avi Rozen, who had come to the States following the death of his father in the Yom Kippur War of 1973. At the time, Avi was flunking out of school. In an experimental program, he and others struggling with their grades were given a chance to rehabilitate their college careers and transcripts during a long summer in the high mountains and deserts of Arizona. Al-Falah, Rozen’s elder by fifteen years, led the program.

It was a forty-day course in survival, the kind of experience Arabs and Israelis of al-Falah and Rozen’s era had been steeped in from their youth. Over those forty days, the two men made a connection. Muslim and Jewish, both regarded land—sometimes the very same land—as sacred. Out of this shared respect for the soil gradually grew a respect for each other, despite their differences in belief and the strife that divided their people.

Or so Lou had been told.

In truth, Lou was skeptical of the happy face that had been painted on the relationship between al-Falah and Rozen. To him it smelled like PR, a game Lou knew from his own corporate marketing experience. Come be healed by two former enemies who now raise their families together in peace. The more he thought about the al-Falah/Rozen story, the less he believed it.

If he had examined himself at that moment, Lou would have been forced to admit that it was precisely this Middle Eastern intrigue surrounding Camp Moriah, as it was called, that had lured him onto the plane with Carol and Cory. Certainly he had every reason not to come. Five executives had recently left his company, putting the organization in peril. If he had to spend two days away, which al-Falah and Rozen were requiring, he needed to unwind on a golf course or near a pool, not commiserate with a group of despairing parents.

“Thank you for helping us,” he said to al-Falah, feigning gratitude. He continued watching the girl out of the corner of his eye. She was still shrieking between sobs and both clinging to and clawing at her father. “Looks like you have your hands full here.”

Al-Falah’s eyes creased in a smile. “I suppose we do. Parents can become a bit hysterical on occasions like this.”

Parents? Lou thought. The girl is the one in hysterics. But al-Falah had struck up a conversation with Cory before Lou could point this out to him.

“That would be me,” Cory said flippantly. Lou registered his disapproval by digging his fingers into Cory’s bicep. Cory flexed in response.

“I’m glad to meet you, Son,” al-Falah said, taking no notice of Cory’s tone. “I’ve been looking forward to it.” Leaning in, he added, “No doubt more than you have. I can’t imagine you’re very excited to be here.”

Cory didn’t respond immediately. “Not really. No,” he finally said, pulling his arm out of his father’s grasp. He reflex-ively brushed his arm, as if to dust off any molecular fibers that might have remained from his father’s grip.

“Don’t blame you,” al-Falah said as he looked at Lou and then back at Cory. “Don’t blame you a bit. But you know something?” Cory looked at him warily. “I’d be surprised if you feel that way for long. You might. But I’d be surprised.” He patted Cory on the back. “I’m just glad you’re here, Cory.”

“Yeah, okay,” Cory said less briskly than before. Then, back to form, he chirped, “Whatever you say.”

Lou shot Cory an angry look.

“So, Lou,” al-Falah said, “you’re probably not too excited about being here either, are you?”

“On the contrary,” Lou said, forcing a smile. “We’re quite happy to be here.”

Carol, standing beside him, knew that wasn’t at all true. But he had come. She had to give him that. He often complained about inconveniences, but in the end he most often made the inconvenient choice. She reminded herself to stay focused on this positive fact—on the good that lay not too far beneath the surface.

“We’re glad you’re here, Lou,” al-Falah answered. Turning to Carol, he added, “We know what it means for a mother to leave her child in the hands of another. It is an honor that you would give us the privilege.”

“Thank you, Mr. al-Falah,” Carol said. “It means a lot to hear you say that.”

“Well, it’s how we feel,” he responded. “And please, call me Yusuf. You too Cory,” he said, turning in Cory’s direction. “In fact, especially you. Please call me Yusuf. Or ‘Yusi,’ if you want. That’s what most of the youngsters call me.”

In place of the cocksure sarcasm he had exhibited so far, Cory simply nodded.

A few minutes later, Carol and Lou watched as Cory loaded into a van with the others who would be spending the next sixty days in the wilderness. All, that is, except for the girl Jenny, who, when she realized her father wouldn’t be rescuing her, ran across the street and sat belligerently on a concrete wall. Lou noticed she wasn’t wearing anything on her feet. He looked skyward at the morning Arizona sun. She’ll have some sense burned into her before long, he thought.

Jenny’s parents seemed lost as to what to do. Lou saw Yusuf go over to them, and a couple of minutes later the parents went into the building, glancing back one last time at their daughter. Jenny howled as they stepped through the doors and out of her sight.

Lou and Carol milled about the parking lot with a few of the other parents, engaging in small talk. They visited with a man named Pettis Murray from Dallas, Texas, a couple named Lopez from Corvallis, Oregon, and a woman named Elizabeth Wingfield from London, England. Mrs. Wingfield was currently living in Berkeley, California, where her husband was a visiting professor in Middle Eastern studies. Like Lou, her attraction to Camp Moriah was mostly due to her curiosity about the founders and their history. She was only reluctantly accompanying her nephew, whose parents couldn’t afford the trip from England.

Carol made a remark about it being a geographically diverse group, and though everyone nodded and smiled, it was obvious that these conversations were barely registering. Most of the parents were preoccupied with their kids in the van and cast furtive glances in their direction every minute or so. For Lou’s part, he was most interested in why nobody seemed to be doing anything about Jenny.

Lou was about to ask Yusuf what he was going to do so that the vehicle could set out to take their children to the trail. Just then, however, Yusuf patted the man he was talking to on the back and began to walk toward the street. Jenny didn’t acknowledge him.

“Jenny,” he called out to her. “Are you alright?”

“What do you think?” she shrieked back. “You can’t make me go, you can’t!”

“You’re right, Jenny, we can’t. And we wouldn’t. Whether you go will be up to you.”

Lou turned to the van hoping Cory hadn’t heard this. Maybe you can’t make him go, Yusi, he thought, but I can. And so can the court.

Yusuf didn’t say anything for a minute. He just stood there, looking across the street at the girl while cars occasionally passed between them. “Would you mind if I came over, Jenny?” he finally called.

She didn’t say anything.

“I’ll just come over and we can talk.”

Yusuf crossed the street and sat down on the sidewalk. Lou strained to hear what they were saying but couldn’t for the distance and traffic.

“Okay, it’s about time to get started everyone.”

Lou turned toward the voice. A short youngish-looking man with a bit of a paunch stood at the doorway to the building, beaming what Lou thought was an overdone smile. He had a thick head of hair that made him look younger than he was. “Come on in, if you would,” he said. “We should probably be getting started.”

“What about our kids?” Lou protested, pointing at the idling vehicle.

“They’ll be leaving shortly, I’m sure,” the man responded. “You’ve had a chance to say good-bye, haven’t you?”

They all nodded.

“Good. Then this way, if you please.”

Lou took a last look at the vehicle. Cory was staring straight ahead, apparently paying no attention to them. Carol was crying and waving at him anyway as the parents shuffled through the door.

“Avi Rozen,” said the bushy-haired man as he extended his hand to Lou.

“Lou and Carol Herbert,” Lou replied in the perfunctory tone he used with those who worked for him.

“Pleasure to meet you, Lou. Welcome, Carol,” Avi said with an encouraging nod.

They filed through the door with the others and went up the stairs. This was to be their home for the next two days. Two days during which we better learn what they’re going to do to fix our son, Lou thought.

Lou looked around the room. Ten or so chairs were arranged in a U shape. Lou sat in the first of these. Jenny’s father and mother were sitting across from him. The mother’s face was drawn tight with worry. Blotchy red patches covered the skin on her neck and stretched across her face. The father was staring vacantly at the ground.

Behind them, Elizabeth Wingfield (a bit overdressed, Lou thought, in a chic business suit) was helping herself to a cup of tea at the bar against the far wall of the room.

Meanwhile, Pettis Murray, the fellow from Dallas, was taking his seat about halfway around the semicircle to Lou’s right. He seemed pretty sharp to Lou, with the air of an executive— head high, jaw set, guarded.

The couple just to the other side of Pettis couldn’t have been more in contrast. Miguel Lopez was an enormous man, with tattoos covering almost every square inch of his bare arms. He wore a beard and mustache so full that a black bandana tied tightly around his head was the only thing that kept his face from being completely obscured by hair. By contrast, his wife, Ria, was barely over five feet tall with a slender build. In the parking lot, she had been the most talkative of the group, while Miguel had mostly stood by in silence. Ria now nodded at Lou, the corners of her mouth hinting at a smile. He tipped his head toward her in acknowledgment and then continued scanning the room.

In the back, keeping to herself, was a person Lou hadn’t yet met—an African American woman he guessed to be somewhere in her midforties. Unlike the others with children in the program, she had not been outside to see them off. Lou wondered whether she had brought a child, worked for Camp Moriah, or had some other reason for being there.

Lou turned to the front of the room, arms folded loosely across his chest. One thing he hated was wasting time, and it seemed they had been doing nothing but that since they’d arrived.

“Thank you all for coming,” Avi said as he walked to the front. “I’ve been looking forward to meeting you in person and to getting to know your children. First of all, I know you’re concerned about them—Teri and Carl, you especially,” he said, glancing for a moment over at Jenny’s parents. “Your presence here is a testament to your love for your children. You needn’t trouble yourself about them. They will be well taken care of.

“In fact,” he said after a brief pause, “they are not my primary concern.”

“Who is, then?” Ria asked.

“You are, Ria. All of you.”

“We are?” Lou repeated in surprise.

“Yes,” Avi smiled.

Lou was never one to back down from a perceived challenge. In Vietnam he had served as a sergeant in the Marine Corps, and the gruesome experience had both hardened and sharpened him. His men referred to him as Hell-fire Herbert, a name that reflected both his loud, brash nature and his consequences-be-damned devotion to his unit. His men both feared and revered him: for most of them, he was the last person on earth they would want to spend a holiday with, but no other leader in the Marines brought more men back alive.

“And why are we your primary concern?” Lou asked pointedly.

“Because you don’t think you should be,” Avi answered.

Lou laughed politely. “That’s a bit circular, isn’t it?”

The others in the group, like spectators at a tennis match, looked back at Avi, anticipating his reply.

Avi smiled and looked down at the ground for a moment, thinking. “Tell us about Cory, Lou,” he said finally. “What’s he like?”

“Cory?”

“Yes.”

“He is a boy with great talent who is wasting his life,” Lou answered matter-of-factly.

“But he’s a wonderful boy,” Carol interjected, glancing warily at Lou. “He’s made some mistakes, but he’s basically a good kid.”

“ ‘Good kid’?” Lou scoffed, losing his air of nonchalance. “He’s a felon for heaven’s sake—twice over! Sure he has the ability to be good, but mere potential doesn’t make him good. We wouldn’t be here if he was such a good kid.”

Carol bit her lip, and the other parents in the room fidgeted uncomfortably.

Sensing the discomfort around him, Lou leaned forward and added, “Sorry to speak so plainly, but I’m not here to celebrate my child’s achievements. Frankly, I’m royally pissed at him.”

“Leave the royalty to me, if you don’t mind,” Mrs. Wing-field quipped. She was seated two chairs to Lou’s right, on the other side of Carol.

“Certainly,” he said with a smile. “My apologies to the crown.”

She tipped her head at him.

It was a light moment that all in the room could throw themselves into heavily, as heaviness was what had characterized too much of their recent lives.

“Lou is quite right,” Avi said after the moment had passed. “We are here not because our children have been choosing well but because they have been choosing poorly.”

“That’s what I’m saying,” Lou nodded in agreement.

Avi smiled. “So what, then, is the solution? How can the problems you are experiencing in your families be improved?”

“I should think that’s obvious,” Lou answered directly. “We are here because our children have problems. And Camp Moriah is in the business of helping children overcome their problems. Isn’t that right?”

Carol bristled at Lou’s tone. He was now speaking in his boardroom voice—direct, challenging, and abrasive. He rarely took this tone with her, but it had become the voice of his interactions with Cory over the last few years. Carol couldn’t remember the last time Lou and Cory had had an actual conversation. When they spoke, it was a kind of verbal wrestling match, each of them trying to anticipate the other’s moves, searching for weaknesses they could then exploit to force the other into submission. With no actual mat into which to press the other’s flesh, these verbal matches always ended in a draw: each of them claimed hollow victory while living with ongoing defeat. She silently called heavenward for help, as she had been taught to do by her churchgoing parents. She wasn’t sure there was a heaven or any help to be had, but she broadcast her need all the same.

Avi smiled good-naturedly. “So Lou,” he said, “Cory is a problem. That’s what you’re saying.”

“Yes.”

“He needs to be fixed in some way—changed, motivated, disciplined, corrected.”

“Absolutely.”

“And you’ve tried that?”

“Tried what?”

“Changing him.”

“Of course.”

“And has it worked? Has he changed?”

“Not yet, but that’s why we’re here. One day, no matter how hard a skull he has, he’s going to get it. One way or the other.”

“Maybe,” Avi said without conviction.

“You don’t think your program will work?” Lou asked, incredulously.

“That depends.”

“On what?”

“On you.”

Lou grunted. “How can the success of your program depend on me when you’re the ones who will be working with my son over the coming two months?”

“Because you will be living with him over all the months afterward,” Avi answered. “We can help, but if your family environment is the same when he gets home as it was when he left, whatever good happens here is unlikely to make much of a difference later. Yusuf and I are only temporary surrogates. You and Carol, all of you with your respective children,” he said, motioning to the group, “are the helpers who matter.”

Great, Lou thought. A waste of time.

“You said you want Cory to change,” came a voice from the back, yanking Lou from his thoughts. It was Yusuf, who had finally joined the group.

“Yes,” Lou answered.

“Don’t blame you,” Yusuf said. “But if that is what you want, there is something you need to know.”

“What’s that?”

“If you are going to invite change in him, there is something that first must change in you.”

“Oh yeah?” Lou challenged. “And what would that be?”

Yusuf walked to the whiteboard that covered nearly the entire front wall of the room. “Let me draw something for you,” he said.

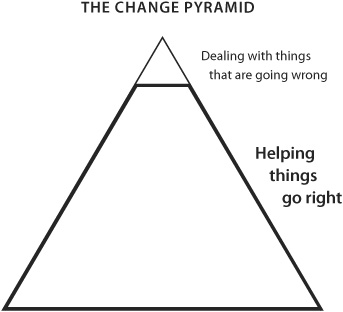

“By the end of the day tomorrow,” Yusuf said, turning to face the group, “we will have formulated a detailed strategy for helping others to change. That strategy will be illustrated by a diagram we call the Change Pyramid. We aren’t yet ready to consider the pyramid in detail, so I’ve drawn only its basic structure. This overall structure will help us to discover a fundamental change that must occur in us if we are going to invite change in others.”

“Okay, I’ll bite,” Lou said. “What fundamental change?”

“Look at the two areas in the pyramid,” Yusuf invited. “Notice that the largest area by far is what I have labeled ‘Helping things go right.’ In comparison, the ‘Dealing with things that are going wrong’ area is tiny.”

“Okay,” Lou said, wondering what significance this had.

Yusuf continued. “The pyramid suggests that we should spend much more time and effort helping things go right than dealing with things that are going wrong. Unfortunately, however, these allocations of time and effort are typically reversed. We spend most of our time with others dealing with things that are going wrong. We try fixing our children, changing our spouses, correcting our employees, and disciplining those who aren’t acting as we’d like. And when we’re not actually doing these things, we’re thinking about doing them or worrying about doing them. Am I right?” Yusuf looked around the room for a response.

“For example, Lou,” he said, “would it be fair to say that you spend much of your time with Cory criticizing and challenging him?”

Lou thought about it. This was no doubt true in his case, but he didn’t want to admit to it so easily.

“Yes, I’d say that’s true,” Carol admitted for him.

“Thanks,” Lou mumbled under his breath. Carol looked straight ahead.

“It’s certainly far too true of me as well,” Yusuf said, coming to Lou’s rescue. “It’s only natural when confronting a problem that we try to correct it. Trouble is, when working with people, this hardly ever helps. Further correction rarely helps a child who is pouting, for example, or a spouse who is brooding, or a coworker who is blaming. In other words, most problems in life are not solved merely by correction.”

“So what do you suggest?” Lou asked. “If your child was into drugs, what would you do, Yusuf? Just ignore it? Are you saying you shouldn’t try to change him?”

“Maybe we should begin with a less extreme situation,” Yusuf answered.

“Less extreme? That’s my life! That’s what I’m dealing with.”

“Yes, but it’s not all that you are dealing with. You and Carol aren’t on drugs, but I bet that doesn’t mean you’re always happy together.”

Lou thought back to the silent treatment Carol had given him on the flight the day before. She didn’t like how he had handled Cory, and she communicated her displeasure by clamming up. Tears often lay just below the surface of her silence. Lou knew what her silence meant—that he, Lou, wasn’t measuring up—and he resented it. He was having enough trouble with his boy; he didn’t think he deserved the silent, teary lectures. “We’re not perfect,” Lou allowed.

“Nor am I with my wife, Lina,” Yusuf said. “And you know what I’ve found? When Lina is upset with me in some way, the least helpful thing I can do is criticize her or try to correct her. When she’s mad, she has her reasons. I might think she’s wrong and her reasons illegitimate, but I’ve never once convinced her of that by fighting back.” He looked at Lou and Carol. “How about you? Has it helped to try to change each other?”

Lou chewed tentatively on the inside of his cheek as he remembered rows he and Carol had gotten into over her silent treatment. “No, I suppose not,” he finally answered. “Not generally, anyway.”

“So for many problems in life,” Yusuf said, “solutions will have to be deeper than strategies of discipline or correction.”

Lou thought about that for a moment.

“But now for your harder question,” Yusuf continued. “What if my child is doing something really harmful, like drugs? What then? Shouldn’t I try to change him?”

“Exactly,” Lou nodded.

“And the answer to that, of course,” Yusuf said, “is yes.”

This caught Lou by surprise, and he swallowed the retort he’d been planning.

“But I won’t invite my child to change if my interactions with him are primarily in order to get him to change.”

Lou got lost in that answer and furrowed his brow. He began to reload his objection.

“I become an agent of change,” Yusuf continued, “only to the degree that I begin to live to help things go right rather than simply to correct things that are going wrong. Rather than simply correcting, for example, I need to reenergize my teaching, my helping, my listening, my learning. I need to put time and effort into building relationships. And so on. If I don’t work the bottom part of the pyramid, I won’t be successful at the top.

“Jenny, for example,” he continued, “is currently outside on a wall refusing to join the others on the trail.”

Still? Lou thought to himself.

“She doesn’t want to enter the program,” Yusuf continued. “That’s understandable, really. What seventeen-year-old young woman is dying to spend sixty days sleeping on the hard ground and living on cornmeal and critters they can capture with homemade spears?”

“That’s what they have to do out there?” Ria asked.

“Well, kind of,” Yusuf smiled. “It’s not quite that primitive.”

“But it’s close,” Avi interjected with a chuckle.

Ria widened her eyes and rocked backward into her seat, trying to imagine how her boy would do in this environment. By contrast, her husband, Miguel, nodded approvingly.

“So what do we do?” Yusuf asked rhetorically. “Any attempt to discipline or to correct her behavior is unlikely to work, wouldn’t you agree?”

“Oh, I don’t know,” Lou said, arguing more out of habit now than conviction. “If it were me, I would have gone over to her and told her to get her backside over to the vehicle.”

“Right gentlemanly of you, Lou,” Elizabeth quipped.

“And what if she had refused?” Yusuf asked.

Lou looked at Elizabeth. “Then I would have made her go,” he said, carefully articulating each word.

“But Camp Moriah is a private organization with no authority of the state,” Yusuf responded, “and no desire to create additional problems by trying to bully people into doing what we want them to do. We do not force children to enroll.”

“Then you have a problem,” Lou said.

“Yes, we certainly do,” Yusuf agreed. “The same problem we each have in our families. And the same problem countries have with one another. We are all surrounded by other autonomous people who don’t always behave as we’d like.”

“So what can you do when that’s the case?” Ria asked.

“Get really good at the deeper matters,” Yusuf answered, “at helping things to go right.”

“And how do you get good at that?” Ria followed up.

“That is exactly what we are here to talk about for the next two days,” Yusuf answered. “Let’s begin with the deepest matter of all, an issue I would like to introduce by going back some nine hundred years to a time when everything was going wrong.”

The bestselling sequel to Leadership and Self-Deception

Available from your favorite bookseller, from Arbinger www.arbinger.com or from Berrrett-Koehler Publishers, www.bkconnection.com 800-929-2929

“The Anatomy of Peace could change the face of humanity.”

—Marion Blumenthal Lazan, Holocaust survivor and bestselling author

“A can’t-put-it-down, enthralling story of peacemaking.”

—The Reverend Victor de Waal, former Dean of Canterbury Cathedral

“A book with the potential to completely change our personal lives and the world itself.”

—Rabbi Benjamin Blech, Professor of Talmud, Yeshiva University

“I loved Leadership and Self-Deception, and The Anatomy of Peace takes it to the next level, personally and professionally.”

—Adel Al-Saleh, President, IMS Europe, Middle East and Africa

“The most powerful tool I’ve seen for fInding real, lasting peace—in families, organizations, communities, and nations.”

—Pamela Richarde, Past President, International Coach Federation