“Now at first you’re going to think this is a silly story. It’s not even a workplace story. We’ll apply it to the workplace when we get a little more under our belts. Anyway, it’s just a simple little story — mundane even. But it illustrates well how we get in the box in the first place.

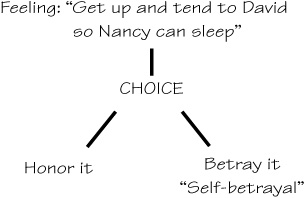

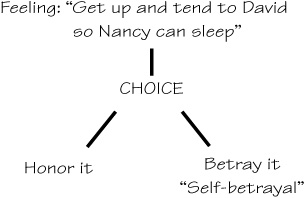

“One night a number of years ago, when David was just an infant, I was awakened by his wailing cries. He was probably four months old or so at the time. I remember glancing at the clock. It was around one in the morning. In the flash of that moment, I had an impression or a sense or a feeling — a thought of something I should do. It was this: ‘Get up and tend to David so that Nancy can sleep.’

“If you think about it, this sort of sense is very basic,” he continued. “We’re all people. And when we’re out of the box and seeing others as people, we have a very basic sense about others — namely that, like ourselves, they have hopes, needs, cares, and fears. And on occasion, as a result of this sense, we have impressions of things to do for others — things we think might help them, things we can do for them, things we want to do for them. You know what I’m talking about?”

“Sure, that’s clear enough,” I said.

“This was such an occasion — I felt a desire to do something for Nancy. But you know what? I didn’t act on it. I just stayed in the bed, listening to David wail.”

I could relate. I’d waited out Todd and Laura plenty of times.

“You might say I ‘betrayed’ my sense of what I should do for Nancy,” he said. “That’s sort of a strong way to say it, but I just mean that in acting contrary to my sense of what was appropriate, I betrayed my own sense of how I should be toward another person. So we call such an act ‘self-betrayal.’ ”

At that, he turned to the board to write. “Do you mind if I erase this diagram?” he asked, pointing at the diagram of the two ways of doing behavior.

“No, that’s fine,” I said. “I’ve got it.”

In its place, in the top left corner of the board, he wrote the following:

“Self-betrayal”

1. An act contrary to what I feel I should do for another is called an act of “self-betrayal.”

“Self-betrayal is one of the most common things in the world, Tom,” Kate added, in an easy manner. “It might help to hear a few more examples.” She looked at Bud. “Would you mind?”

“Please.”

“Yesterday I was at Rockefeller Center in New York,” she began. “I got into the elevator, and as the door started to close, I saw someone scurry around the corner and race toward the elevator. In that instant, I had a sense that I should catch the door for him. But I didn’t. I just let it close, my last view being that of his outstretched, lunging arm. Have you ever had that experience?”

I had to admit I had and nodded sheepishly. “Or how about these: Think of a time when you felt you should help your child or your spouse but then decided not to. Or a time when you felt you should apologize to someone but never got around to doing it. Or a time when you knew you had some information that would be helpful to a coworker, but you kept it to yourself. Or a time when you knew you needed to stay late to finish some work for someone but went home instead — without bothering to talk to that person about it. I could go on and on, Tom. I’ve done all of these, as I bet you have, too.”

“Pretty much, yeah.”

“They’re all examples of self-betrayal — times when I had a sense of something I should do for others but didn’t do it.”

Kate paused, and Bud stepped in. “Now think about it, Tom. This is hardly a monumental idea. It’s about as simple as it comes. But its implications are astounding. And astoundingly unsimple. Let me explain.

“Let’s go back to the crying-baby story. Picture the moment. I felt I should get up so that Nancy could sleep, but then I didn’t do it. I just stayed lying there next to Nancy, who also was just lying there.”

As Bud was saying this, he drew the following in the middle of the board:

“Now, in this moment, as I’m just lying there listening to our wailing child, how do you imagine I might’ve started to see, and feel about, Nancy?”

“Well, she probably seemed kind of lazy to you,” I said.

“Okay, ‘lazy,’ ” Bud agreed, adding it to the diagram.

“Inconsiderate,” I added. “Maybe unappreciative of all you do. Insensitive.”

“These are coming pretty easily to you, Tom,” Bud said with a wry smile, adding what I’d said to the diagram.

“Yeah, well, I must have a good imagination, I guess,” I said, playing along. “I wouldn’t know any of this for myself.”

“No, of course you wouldn’t,” said Kate. “Nor would you either, would you, Bud? The two of you are probably too busy sleeping to be aware of any of this,” she said, chuckling.

“Aha, the battle is joined,” laughed Bud. “But thank you, Kate. You raise an interesting point about sleeping.” Turning back to me, he asked, “What do you think, Tom? Was Nancy really asleep?”

“Oh … maybe, but I doubt it.”

“So you think she was faking it — pretending to sleep?”

“That’d be my guess,” I said.

Bud wrote “faker” on the diagram.

“But hold on a minute, Bud,” Kate objected. “Maybe she was asleep—and probably, from the sound of it, because she was so worn out from doing everything for you,” Kate added, obviously happy with the jab.

“Okay, good point,” Bud said with a grin. “But remember, whether she actually was asleep is less important right now than whether I was thinking she was asleep. We’re talking now about my perception once I betrayed myself. That’s the point.”

“I know,” Kate said, settling back into her chair. “I’m just having fun. If it were my example, you’d have plenty to pile on about.”

“So from the perspective of that moment,” Bud continued, looking at me, “if she was just feigning sleep and letting her child wail, what kind of mom do you suppose I thought she was being?”

“Probably a pretty lousy one,” I said.

“And what kind of wife?”

“Again, pretty lousy — inconsiderate, thinks you don’t do enough, and so on.”

Bud wrote both of these on the diagram.

“So, here I am,” he said, backing away from the diagram and reading what he had written. “Having betrayed myself, we can imagine that I might’ve started to see my wife in that moment as lazy, inconsiderate, taking me for granted, insensitive, a faker, a lousy mom, and a lousy wife.”

“Wow, Bud. Congratulations,” said Kate, sarcastically. “You’ve managed to completely vilify one of the best people I know.”

“I know. It’s scary, isn’t it?”

“I’ll say.”

“But it’s worse than that, even,” Bud said. “That’s how I started to see Nancy. But having betrayed myself, how do you suppose I started to see myself?”

“Oh, you probably saw yourself as the victim — as the poor guy who couldn’t get the sleep he needed,” Kate replied.

“That’s right,” Bud said, adding “victim” to the diagram.

“And you would’ve seen yourself as hardworking,” I added. “The work you had to do the next morning probably seemed pretty important to you.”

“Good, Tom — that’s right,” Bud said, adding “hardworking” and “important.”

“How about this?” he asked after a pause. “What if I’d gotten up the night before? How do you suppose I would’ve seen myself if that had been the case?”

“Oh, as ‘fair,’ ” Kate answered.

“Yes. And how about this?” he added. “Who is sensitive enough to hear the child?”

I had to laugh. All of this — the way Bud saw Nancy and the way he saw himself — seemed on the one hand so absurd and laughable but on the other hand so common. “Well, you were the sensitive one, obviously,” I said.

“And if I’m sensitive to my child, then what kind of dad do I think I am?”

“A good one,” Kate answered.

“Yes. And if I’m seeing myself as all of these,” he said, pointing to the board — “if I see myself as ‘hardworking,’ ‘fair,’ ‘sensitive,’ a ‘good dad,’ and so on — then what kind of husband do I think I am?”

“A really good husband — especially putting up with a wife like the one you were thinking you had,” Kate said.

“Yes,” Bud said, adding to the list. “So look what we have.”

“Let’s think about this diagram. For starters, look at how I started to see Nancy after I betrayed myself — as lazy, inconsiderate, and so on. Now think of this: Do these thoughts and feelings about Nancy invite me to reconsider my decision and do what I felt I should do for her?”

“Not at all,” I said.

“What do they do for me?” Bud asked.

“Well, they justify your not doing it. They give you reasons to stay in bed and not tend to David.”

“That’s right,” Bud said, turning to the board. He added a second sentence to his description of self-betrayal:

“Self-betrayal”

1. An act contrary to what I feel I should do for another is called an act of “self-betrayal.”

2. When I betray myself, I begin to see the world in a way that justifies my self-betrayal.

“If I betray myself,” Bud said as he backed away from the board, “my thoughts and feelings will begin to tell me that I’m justified in whatever I’m doing or failing to do.”

He sat back down, and I thought of Laura.

“For a few minutes,” he said, “I want to examine how my thoughts and feelings do that.”