“Think about yesterday,” Lou continued. “You just said that it felt like something changed you. We need to think about that a little more carefully.”

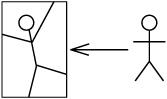

He moved toward the board. “I want to talk about self-betrayal and the box for a moment—to make something clear that may not have been made explicit yet.” He drew the following diagram:

“To begin with, here’s a picture of what life is like in the box,” he said, pointing at his drawing. “The box is a metaphor for how I’m resisting others. By ‘resisting,’ I mean that my self-betrayal isn’t passive. In the box, I’m actively resisting what the humanity of others calls me to do for them.

“For example,” he said, pointing to Bud’s story on the board, “in the story here about Bud’s failing to get up so that Nancy could sleep, that initial feeling was an impression he had of something he should do for Nancy. He betrayed himself when he resisted that sense of what he should do for her, and in resisting that sense, he began to focus on himself and to see her as being undeserving of help. His self-deception—his ‘box’—is something he created and sustained through his active resistance of Nancy. This is why it’s futile, as Bud was saying a few minutes ago, to try to get out of the box by focusing further on ourselves: In the box, everything we think and feel is part of the lie of the box. The truth is, we change in the moment we cease resisting what is outside our box—others. Does that make sense?”

“Yeah, I think so.”

“In the moment we cease resisting others, we’re out of the box—liberated from self-justifying thoughts and feelings. This is why the way out of the box is always right before our eyes—because the people we’re resisting are right before our eyes. We can stop betraying ourselves toward them—we can stop resisting the call of their humanity upon us.”

“But what can help me to do that?” I asked.

Lou looked at me thoughtfully. “There’s something else you should understand about self-betrayal—something that may give you the leverage you’re looking for. Think about your experience yesterday with Bud and Kate. How would you characterize it? Would you say that you were basically in or out of the box toward them?”

“Oh, out, for sure,” I said. “At least most of the time,” I added, giving Bud a sheepish grin. He smiled in return.

“But you’ve also indicated that you were in the box toward Laura yesterday. So there is a sense in which you were both in and out of the box at the same time—in the box toward Laura but out of the box toward Bud and Kate.”

“Yeah, I guess that’s right.”

“This is an important point, Tom. Toward any one person or group of people, I’m either in or out of the box at any given moment. But since there are many people in my life—some that I may be more in the box toward than others—in an important sense, I can be both in and out of the box at the same time. In the box toward some people and out toward others.

“This simple fact can give us leverage to get out of the box in the areas of our lives where we may be struggling. In fact, that’s what happened to you yesterday. Let me show you what I mean.”

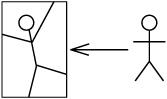

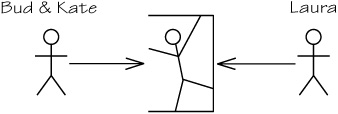

Lou walked to the board and modified his drawing.

“Here’s how we might depict what you were like yesterday,” he said, standing to the side of the board. “You were in the box toward Laura but out of the box as you engaged with Bud and Kate. Now notice: Although you were resistant to Laura’s needs because you were in the box toward her, you nevertheless retained a sense of what people generally might need because you were out of the box toward others—namely, Bud and Kate. This sense that you felt and honored regarding Bud and Kate, combined with the continual call of Laura’s humanity to you—which is always there—is what made getting out of the box toward Laura possible.

“So although it’s true that there is nothing we can think of and do from within the box to get ourselves out, the fact that we are almost always both in and out of the box at the same time, albeit in different directions, means that we always have it within our capacity to find our way to a perspective within ourselves that is out of the box. This is what Bud and Kate did for you yesterday—they supplied for you an out-of-the box environment from which you were able to consider your in-the-box relationships with new clarity. From the context of your relationships with Bud and Kate, you were able to think of a number of things you could do to help reduce your in-the-box moments and heal your in-the-box relationships. In fact, there is one thing in particular that you did while you were out of the box toward Bud and Kate that helped you to get out of the box toward Laura.”

My mind searched for the answer. “What did I do?”

“You questioned your own virtue.”

“I what?”

“You questioned your own virtue. While you were out of the box, you listened to what Bud and Kate taught you about being in the box. And then you applied it to your own personal situations. The out-of-the-box nature of your experience with Bud and Kate invited you to do something that we never do in the box—it invited you to question whether you were in fact as out of the box as you had assumed you were in other areas of your life. And what you learned from the vantage point of that out-of-the-box space transformed your view of Laura.

“Now that probably didn’t happen right off the bat,” he continued, “but I’d bet there was a moment when it was as if the light came pouring in—a moment when your blaming emotions toward Laura seemed to evaporate, and she suddenly seemed different to you than she had the moment before.”

That was exactly how it happened, I thought to myself. I remembered that moment—when I saw the hypocrisy in my anger. It was as if everything changed in an instant. “That’s true,” I said. “That’s what happened.”

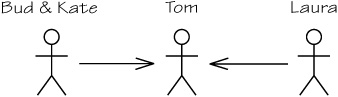

“Then we need to modify this drawing still more,” Lou said, turning to the board. When he finished, he backed away from the board and said, “This is how you looked when you left last night.”

“You were seeing and feeling straightforwardly. Laura seemed different to you because in the moment you got out of the box toward her, you no longer had the need to blame her and inflate her faults.”

Lou sat down. “In a way,” he said, “this is quite a miraculous thing. But in another way, it’s the most common thing in the world. It happens all the time in our lives—usually on very small matters that are quickly forgotten. All of us are both in the box and out of the box toward others. The more we can find our way to the out-of-the-box vantage points within us, the more readily we will be able to shine light on the in-the-box justifications we are carrying. All of a sudden, because of the presence of the people who continually stand before us, and because of what we know as we stand out of the box in relation to other people, our box can be penetrated by the humanity of those whom we’ve been resisting. When that happens, we know in that moment what we need to do: We need to honor them as people. And in that moment—the moment I see another as a person, with needs, hopes, and worries as real and legitimate as my own—I am out of the box toward him. What remains for me, then, is the question of whether I am going to stay out.”

“You might think about it this way,” Bud interjected. “Look again at this story,” he said, pointing to the diagram of his crying-baby story. “When I once again have a feeling of something I desire to do to help another, where am I in this diagram?”

I looked at the board. “You’re at the top again—back at the feeling.”

“Exactly. I’m back out of the box. I can now choose the other way. I can now choose to honor that sense rather than betray it. And that, Tom—acting on the sense or feeling I have recovered of what I can do to help another—is the key to staying out of the box. Having recovered that sense, I am out of the box; by choosing to honor it rather than betray it, I am choosing to stay out of the box.”

“In fact, Tom,” Lou added, “I bet you had a feeling as you left here yesterday that there were some things you needed to do for some people last night. Am I right?”

“Yes,” I said.

“And you did them, didn’t you?” Lou asked.

“Yes, I did.”

“That’s why your night went as it did,” he said. “You got out of the box toward Laura, and Todd for that matter, during your time with Bud and Kate. But your night went well because you stayed out of the box by doing for your family what you felt you should do.”

What Lou said seemed to explain my night with Laura and Todd well enough, but it left me feeling a little confused and overwhelmed about situations in general. How could people be expected to do everything they felt they should do for others? That didn’t seem right.

“Are you saying that in order to stay out of the box, I have to always be doing things for others?”

Lou smiled. “That’s an important question. We need to consider it with some care—maybe with a specific example.” He paused for a moment. “Let’s think about driving. What would you say is your standard attitude toward other drivers on the road?”

I smiled to myself as I recalled a number of characteristic commutes. I remembered waving my fist at a driver who wouldn’t slow down to let me merge, only to discover, after I’d forced my way in, that he was my neighbor. And I remembered glaring at the driver of a maddeningly slow car as I sped around him, only to discover, to my horror, that he was the same neighbor. “I suppose I’m pretty indifferent toward them,” I chuckled, unable to suppress my amusement. “Unless, of course, they’re in my way.”

“It sounds like we went to the same driving school,” Lou quipped. “But you know what? Occasionally I’ve had very different feelings toward other drivers. For example, it sometimes occurs to me that each of these people on the road is just as busy as I am and just as wrapped up in his or her own life as I am in mine. And in these moments, when I get out of the box toward them, other drivers seem very different to me. In a way, I feel that I understand them and can relate to them, even though I know basically nothing about them.”

“Yeah,” I nodded, “I’ve had that experience, too.”

“Good. So you know what I’m talking about. With that kind of experience in mind, let’s consider your question. You’re worried that in order to stay out of the box, you have to do everything that pops into your head to do for others. And that seems overwhelming, if not foolhardy. Am I right?”

“Yes. That’s one way to put it.”

“Well,” said Lou, “we need to consider whether being out of the box creates the overwhelming stream of obligations you’re worried about. Let’s consider the driving situation. First of all, think of the people in the cars far ahead and far behind me. Is my being out of the box likely to make much of a difference in my outward behavior toward them?”

“No, I suppose not.”

“How about toward drivers who are nearer to me? Would my being out of the box change my outward behavior toward them?”

“Probably.”

“Okay, how? What might I do differently?”

I thought of seeing my neighbor in my rearview mirror. “You probably wouldn’t cut people off as much.”

“Good. What else?”

“You’d probably drive more safely, more considerately. And who knows?” I added, thinking of the glare I shot at the man who turned out to be my neighbor, “you might even smile more.”

“All right, good enough. Now notice—do these behavioral changes strike you as overwhelming or burdensome?”

“Well, no.”

“So, in this case, being out of the box and seeing others as people doesn’t mean that I’m suddenly bombarded with burdensome obligations. It simply means that I’m seeing and appreciating others as people while I’m driving, or shopping, or doing whatever it is I am doing.

“In other cases,” he continued, “getting out of the box may mean that I relinquish a prejudice that I have held toward those not like myself—people of a different race, for example, or faith, or culture. I will be less judgmental when I see them as people than when I saw them as objects. I will treat them with more courtesy and respect. Again, however, do such changes seem burdensome to you?”

I shook my head. “On the contrary, they seem freeing.”

“That’s the way it seems to me too,” Lou said. “But let me add one more point.” He leaned forward and folded his arms on the table. “On occasion, there are times when we have specific impressions of additional things we should do for others, particularly toward people we spend more time with—family members, for example, or friends or work associates. We know these people; we have a pretty good sense of their hopes, needs, cares, and fears; and we’re more likely to have wronged them. All of this increases the obligation we feel toward them, as well it should.

“Now, as we’ve been talking about, in order to stay out of the box, it’s critical that we honor what our out-of-the-box sensibility tells us we should do for these people. However—and this is important—this doesn’t necessarily mean that we end up doing everything we feel would be ideal. For we have our own responsibilities and needs that require attention, and it may be that we can’t help others as much or as soon as we wish we could. In such cases, we will have no need to blame them and justify ourselves because we will still be seeing them as people that we want to help even if we are unable to help at that very moment or in the way we think would be ideal. We simply do the best we can under the circumstances. It may not be the ideal, but it will be the best we can do— offered because we want to do it.”

Lou looked at me steadily. “You’ve learned about self-justifying images, haven’t you?”

“Yes.”

“Then you understand how we live insecurely when we’re in the box, desperate to show that we’re justified—that we’re thoughtful, for example, or worthy or noble. It can feel pretty overwhelming always having to demonstrate our virtue. In fact, when we’re feeling overwhelmed, it generally isn’t our obligation to others but our in-the-box desperation to prove something about ourselves that we find overwhelming. If you look back on your life, I think you’ll find that that’s the case—you’ve probably felt overwhelmed, over-obligated, and overburdened far more often in the box than out. To begin with, you might compare your night last night with the nights that came before.”

That’s true, I thought. Last night—the first time in a while that I’d actually gone out of my way to do something for Laura and Todd—was the easiest night I’d had in I don’t know how long.

Lou paused for a few moments, and Bud asked, “Does that help with your question, Tom?”

“Yeah. It helps a lot.” Then I smiled at Lou. “Thanks.”

Lou nodded at me and settled back in his chair, apparently satisfied. He looked past me, out the window. Bud and I waited for him to speak.

“As I sat there those many years ago in that seminar room in Arizona,” he said finally, “learning from others just as you’ve learned here from Bud and Kate, my boxes started to melt away. I felt deep regret at how I’d acted toward the people in my company. And in the moment I felt that regret, I was out of the box toward them.

“The future of Zagrum depended,” he continued, “on whether I could stay out of the box. But I knew that in order to stay out, there were certain things I had to do. And fast.”