“So what’s this something deeper?” I asked curiously.

“What I’ve already introduced to you—self-deception,”

Bud replied. “Whether I’m in or out of the box.”

“Okay,” I said slowly, wanting to know more.

“As we’ve been talking about, no matter what we’re doing on the outside, people respond primarily to how we’re feeling about them on the inside. And how we’re feeling about them depends on whether we’re in or out of the box concerning them. Let me illustrate that point further with a couple of examples.

“About a year ago, I flew from Dallas to Phoenix on a flight that had open seating. While boarding, I overheard the boarding agent say that the plane was not sold out but that there would be very few unused seats. I felt lucky and relieved to find a window seat open with a vacant seat beside it about a third of the way back on the plane. Passengers still in need of seats continued streaming down the aisle, their eyes scanning and evaluating the desirability of their dwindling seating options. I set my briefcase on the vacant middle seat, took out that day’s paper, and started to read. I remember peering over the top corner of the paper at the people who were coming down the aisle. At the sight of body language that said my briefcase’s seat was being considered, I spread the paper wider, making the seat look as undesirable as possible. Do you get the picture?”

“Yeah.”

“Good. Now let me ask you a question: On the surface, what behaviors was I engaged in on the plane—what were some of the things I was doing? ”

“Well, you were being kind of a jerk, for one thing,” I answered.

“Now that’s certainly true,” he said, breaking into a broad smile, “but it’s not quite what I mean—not yet, anyway. I mean, what specific actions was I taking on the plane? What was my outward behavior?”

I pictured the situation. “You were … taking two seats. Is that the kind of thing you mean?”

“Sure. What else?”

“Uh … you were reading the paper. You were watching for people who might want to sit in the seat next to you. To be very basic, you were sitting.”

“Okay, good enough,” said Bud. “Here’s another question: While I was doing those behaviors, how was I seeing the people who were looking for seats? What were they to me?”

“I’d say that you saw them as threats, maybe nuisances or problems—something like that.”

Bud nodded. “Would you say that I considered the needs of those still looking for seats to be as legitimate as my own?”

“Not at all. Your needs counted, and everyone else’s were secondary—if that,” I answered, surprised by my bluntness.

“You were kind of seeing yourself as the kingpin.”

Bud laughed, obviously enjoying the comment. “Well said, well said.” Then he continued, more seriously, “You’re right. On that plane, if others counted at all, their needs and desires counted far less than mine. Now compare that experience with this one: About six months ago, Nancy and I took a trip to Florida. Somehow there was a mistake in the ticketing process, and we weren’t seated together. The flight was mostly full, and the flight attendant was having a difficult time trying to find a way to seat us together. As we stood in the aisle trying to figure out a solution, a woman holding a hastily folded newspaper came up behind us, from the rear of the plane, and said, ‘Excuse me—if you need two seats together, I believe the seat next to me is vacant. I’d be happy to sit in one of your seats.’

“Now think of this woman. How would you say that she saw us —did she see us as threats, nuisances, or problems?”

“No,” I said, shaking my head. “It seems like she just saw you as people in need of seats who would like to sit together. That’s probably more basic than what you’re looking for, but—”

“On the contrary,” said Bud, “that’s a terrific way to put it. She just saw us as people—we’re going to come back to that in a moment. Now let’s compare the way this woman apparently saw others with the way I saw those who were loading onto the plane in my story involving the briefcase. You said that I saw myself as kind of the kingpin—more important than others, with needs that were greater.”

I nodded.

“Is that the way this woman seemed to see herself and others?” he asked. “Did she, like me, seem to privilege her own needs and desires over the needs and desires of others?”

“It doesn’t seem like it, no,” I answered. “It’s sort of like from her point of view, under the circumstances, your needs and her needs counted about the same.”

“That’s how it felt,” Bud said, nodding. He got up and walked toward the far end of the conference table. “Here we have two situations in which a person was seated on a plane next to an empty seat, evidently reading the paper and observing others who were still in need of seats on the plane. That’s what was happening on the surface—behaviorally.”

He opened two large mahogany doors in the wall at the far end of the table, revealing a large whiteboard. “But notice how different this similar experience was for me and for this woman. I minimized others; she didn’t. I felt anxious, uptight, irritated, threatened, and angry, while she appeared to have had no such negative emotions at all. I sat there blaming others who might be interested in my briefcase’s seat— maybe one looked too happy, another too grim, another had too many carry-ons, another looked too talkative, and so on. She, on the other hand, seemed not to have blamed but to have understood—whether happy, grim, loaded with carry-ons, talkative, or not—they needed to sit somewhere. And if so, why shouldn’t the seat next to her—and in her case, even her own seat—be as rightly theirs as any others?

“Now here’s a question for you,” Bud continued. “Isn’t it the case that the people getting on both planes were people with comparable hopes, needs, cares, and fears, and that all of them had more or less the same need to sit?”

That seemed about right. “Yes. I’d agree with that.”

“If that’s true, then I had a big problem—because I wasn’t seeing the people on the plane like that at all. My view was that I somehow was entitled or superior to those who were still looking for seats. Which is to say that I wasn’t really seeing them as people at all. They were more like objects to me in that moment than people.”

“Yeah, I can see that,” I agreed.

“Notice how my view of both myself and others was distorted from what we agreed was the reality,” Bud said. “Although the truth was that all of us were people with more or less the same need to sit, I wasn’t seeing the situation that way. So my view of the world was a systematically incorrect way of seeing others and myself. I saw others as less than they were—as objects with needs and desires somehow secondary to and less legitimate than mine. But I couldn’t see the problem with what I was doing. I was self-deceived—or, in the box. The lady who offered us her seat, on the other hand, saw others and the situation clearly, without bias. She saw others as they were, as people like herself, with similar needs and desires. She saw straightforwardly. She was out of the box.

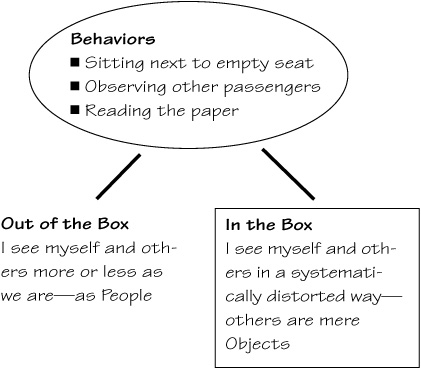

“So the inner experiences of two people,” he went on, “although they exhibited the same outward behaviors, were entirely different. And this difference is very important. I want to emphasize it with a diagram.” At this, he turned to the board and spent a minute drawing the following:

“It’s like this, Tom,” Bud said, stepping to the side of the board so that I could see. “Whatever I might be ‘doing’ on the surface—whether it be, for example, sitting, observing others, reading the paper, whatever—I’m being one of two fundamental ways when I’m doing it. Either I’m seeing others straightforwardly as they are—as people like me who have needs and desires as legitimate as my own—or I’m not. As I heard Kate put it once: One way, I experience myself as a person among people. The other way, I experience myself as the person among objects. One way, I’m out of the box; the other way, I’m in the box. Does that make sense?”

I was thinking about a situation that had occurred a week earlier. Someone in my department had made herself into a terrible nuisance, and I couldn’t see how this in-the-box and out-of-the-box distinction applied. In fact, if anything, the situation seemed to undercut what Bud was talking about. “I’m not sure,” I said. “Let me give you a situation and you tell me how it fits.”

“Fair enough,” he said, taking his seat.

“I have a conference room around the corner from my office where I often go to think and strategize. The people in my department know that the room is like a second office to me and are careful now, after a few altercations over the last month, not to schedule it without my knowing. Last week, however, someone in the department went in and used it. Not only did she use the room without scheduling it, but she erased all my notes from the whiteboard. What do you think of that?”

“Under the circumstances, I’d say that it was pretty poor judgment on her part.”

Nodding, I said, “I was peeved, to say the least. It took me a while to reconstruct what I had done, and I’m still not sure that I have everything right.”

I was about to tell more—about how I immediately had her called into my office, refused a handshake, and then told her without even asking her to sit down that she was never to do that again or she would be looking for a new job. But then I thought better of it. “How does self-deception fit into that scenario?” I asked.

“Let me ask you a few questions,” Bud answered, “and then maybe you can tell me. What kinds of thoughts and feelings did you have about this woman when you found out what she’d done?”

“Well … I guess I thought she wasn’t very careful.”

Bud nodded with an inquisitive look that invited me to say more.

“And I suppose I thought it was stupid of her to do what she did without asking anybody.” I paused, and then added, “It was pretty presumptuous of her, don’t you think?”

“Certainly not very wise,” Bud agreed. “Anything more?”

“No, that’s about what I remember.”

“Let me ask you this, then: Do you know what she wanted to use the room for?”

“Well, no. But why should that matter? It doesn’t change the fact that she shouldn’t have been using it, does it?”

“Perhaps not,” Bud answered. “But let me ask you another question: Do you know her name?”

The question caught me by surprise. I thought for a moment. I wasn’t sure I’d ever heard her name. Had my secretary mentioned it? Or did she say it herself when she extended her hand to greet me? I searched my memory, but there was nothing.

But why should that matter, anyway? I thought to myself, emboldened. So I don’t know her name. So what? Does that make me wrong or something? “No, I guess I don’t know it, or I can’t remember,” I said.

Bud nodded. “Now here’s the question I’d really like you to consider. Assuming that this woman is, in fact, careless, stupid, and presumptuous, do you suppose that she’s as careless, stupid, and presumptuous as you accused her of being when all this happened?”

“Well, I didn’t really accuse her.”

“Not in your words, perhaps, but have you had any interaction with her since the incident?”

I thought of the ice-cold reception I gave her and the offer of her hand rebuffed.

“Yeah, just once,” I said meekly.

Bud must have noticed the change in my voice, for he dropped his voice slightly and lost his matter-of-fact tone. “Tom, I want you to imagine that you were her when you met. What do you think she felt from you?”

The answer, of course, was obvious. She couldn’t have felt worse if I’d hit her with a two-by-four. I remembered the tremor in her voice and her uncertain yet hurried steps as she left my office. I wondered now for the first time how I must have hurt her and what she must be feeling. I imagined that she must now be quite insecure and worried, especially since everyone in the department seemed to know about what had happened. “Yeah,” I said slowly, “looking back on it, I’m afraid I didn’t handle the situation very well.”

“Then let me come back to my prior question,” Bud said. “Do you suppose that your view of this woman at the time made her seem worse than she really was?”

I paused before answering, not because I wasn’t sure, but because I wanted to collect my composure. “Well, maybe. But that doesn’t change the fact that she did something she shouldn’t have, does it?” I added.

“Not at all. And we’ll get to that. But right now, the question I want you to consider is this: Whatever she was doing— be it right or wrong—was your view of her more like my view of the people on the plane or more like the view of the woman I told you about?”

I thought about that for a moment.

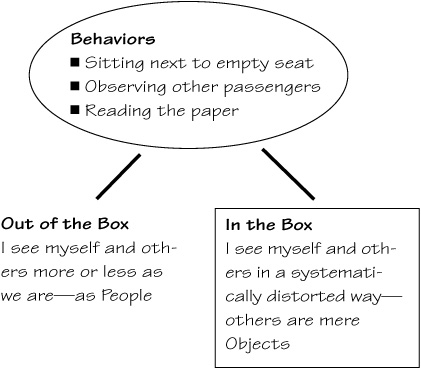

“Think of it this way,” Bud added, pointing at the diagram on the board. “Were you regarding her as a person like yourself, with similar hopes and needs, or was she just an object to you—as you said, just a threat, a nuisance, or a problem?”

“I guess she might’ve been just an object to me,” I said finally.

“So now, how would you say this self-deception stuff applies? Would you say you were in or out of the box?”

“I guess I was probably in it,” I said.

“That’s worth thinking about, Tom. Because this distinction,” he said, pointing again at the diagram, “reveals what was beneath Lou’s success—and Zagrum’s, for that matter. Because Lou was usually out of the box, he saw straightforwardly. He saw people as they were—as people. And he found a way to build a company of people who see that way much more than people in most organizations do. If you want to know the secret of Zagrum’s success, it’s that we’ve developed a culture where people are simply invited to see others as people. And being seen and treated straightforwardly, people respond accordingly. That’s what I felt—and returned— to Lou.”

That sounded great, but it seemed too simplistic to be the element that set Zagrum apart. “It can’t really be that simple, can it, Bud? I mean, if Zagrum’s secret were that basic, everyone would have duplicated it by now.”

“Don’t misunderstand,” said Bud. “I’m not minimizing the importance of, for example, getting smart and skilled people into the company or working hard or any other number of things that are important to Zagrum’s success. But notice— everyone else has duplicated all of that stuff, but they’ve yet to duplicate our results. And that’s because they don’t know how much smarter smart people are, how much more skilled skilled people get, and how much harder hardworking people work when they see, and are seen, straightforwardly—as people.

“And don’t forget,” he continued, “self-deception is a particularly difficult sort of problem. To the extent that organizations are beset by self-deception—and most of them are— they can’t see the problem. Most organizations are stuck in the box.”

That claim hung in the air as Bud reached for his glass of water and took a drink. “By the way,” he added, “the woman’s name is Joyce Mulman.”

“Who … what woman?”

“The person whose hand you refused. Her name is Joyce Mulman.”