HORROR COMICS were a relatively new phenomenon. With costumed heroes losing steam, publishers had to find something new to keep the presses running, and horror movies had been pretty popular, so they decided to give that a try. About the time we were developing Young Romance, Avon put out a title called Eerie Comics. Timely also renamed Marvel Mystery Comics and called it Marvel Tales, with horror stories by a lot of their main talent, including Bill Everett, Syd Shores, and Carl Burgos. Under the imprint Atlas Comics, they would put out dozens of similar titles through the 1950s.

M.C. Gaines had been the editor at All-American Comics, the DC affiliate that put out Flash Comics and Green Lantern. He started life as Maxwell Ginzburg, but nobody ever kept their real name in this business. (Nobody but Joe.) A lot of people called M.C. “Max,” but we knew him as Charlie. The only work we ever did for him was those short Sandman features that appeared as part of the Justice Society stories in All Star Comics. Back then Charlie tried to convince Simon and Kirby to leave DC, despite the fact that they were his partners. But we had a good deal with Liebowitz’s side of the company, so we declined.

Even though he had sold his titles to DC when they became partners, Charlie managed to start a new company, EC Comics, to publish comics about history, science, and religion. His best-known title was Picture Stories from the Bible, which he tried to sell to churches.

When Max died in 1947, his son William took over. Bill Gaines had a different vision for the company, and launched into crime, war, and horror comics. Those featured some of the best artists in the business: Bernie Krigstein, Jack Davis, Al Feldstein, and Wally Wood. One of his best writers was Jack Oleck, who would play an important part in my world later on.

Jack Kirby and I were always looking for something new, so we went to Maurice Rosenfeld at Crestwood and proposed a title called Black Magic. He liked the idea and we put some of our best guys on it, including Mort Meskin, Bill Draut, and John Prentice. A couple of years into the run a young artist named Steve Ditko knocked on our door. As soon as I saw his work I gave him an assignment, and he did three stories for Black Magic. Jack and I produced a lot of the material ourselves — recently I added up the number of horror pages we had done, and it came to more than 300 pages. While everyone else was doing all sorts of lurid gore and violence, in Black Magic we focused on genuine stories.

It wasn’t the hit we’d had with the romance books, but it did well enough. Once we were confident that horror wasn’t going to be a flash in the pan, the series went from bi-monthly to monthly. Our second attempt in the genre was The Strange World of Your Dreams, from an idea suggested by Mort Meskin, whom we listed as associate editor. It came with a unique gimmick — right there on the cover we announced, “We Will Buy Your Dreams!” Inside the book, an advertisement explained the deal.

Black Magic focused more on story than gratuitous violence and gore.

The house in East Williston, and our new Lincoln Cosmopolitan, Ford’s equivalent to the Cadillac.

Richard Temple, student of dreams and fantasy, is a man who has delved into the mystery of this vast, subconscious jigsaw puzzle which affects even our waking hours — he fits the pieces together... Why don’t you join him on his many expeditions into unreality — tell him about your dream — You will receive $25 if your dream is chosen for dramatization!

Richard Temple was about as real as Nancy Hale, and the gimmick didn’t work. Strange World of Your Dreams folded after four issues. Any extra material we had lying around went into Black Magic, which survived for another eight years.

Bill Gaines’s first big horror book carried a cover date of April-May 1950. Black Magic came out with an October-November 1950 cover date. EC’s Tales from the Crypt also came out in October-November, and The Haunt of Fear was a month later. This would lead to something none of us could have anticipated.

While we were at Crestwood, Jack and I put our parents on the payroll. At last we were in good enough shape that we could make certain they were comfortable. Kirby and I each were taking home something like $1,000 a week, which would be more than $10,000 a week today.

On February 12, 1950, at about the time we moved to East Williston, Harriet and I welcomed our second son, Jimmy, into the world. Somehow she and I always managed to schedule each of our new arrivals three years apart.

Life with Harriet was wonderful. She was beautiful, and she was my best friend. We thought alike, we made plans together, and I admired everything about her. She had a likeability about her that everyone recognized. She always was very proud of me, proud of the fact that I was putting out these books from Young Romance to Sick magazine. When I became involved in politics, she thought that made me an intellectual. And in a romantic way, if I’d go somewhere, she always wanted to know where I was.

One time I went to the library to do some reading. While I was sitting there, the phone rang at the front desk. The librarian answered it, then put her hand over the mouthpiece and looked around.

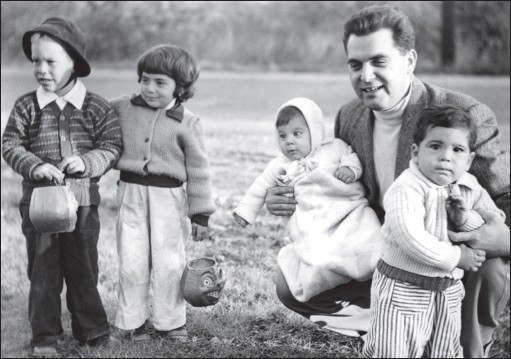

Left to right: Dorian Fliegel, Susan Kirby, Neil Kirby, Jack Kirby, Jon Simon.

Everybody got into the act when we posed for Ken Riley. That’s our sun deck behind the wall.

“Is Joe Simon here?” she said loudly, so everybody could hear. “The creator of Captain America?”

Harriet was always advertising.

She was a real sun worshipper, too. At the East Williston house, we built an addition that extended into our second lot next door. It was a sun deck with a wall all around it. She was always working on her tan. She loved to clean house, but hated to cook. We always had beautiful, spotless houses, as opposed to what I have today. Now I live in what might be generously called an “artist’s studio,” with projects and piles of paper stacked everywhere. I think she would kick me out if she came back now.

We weren’t party people, but we always had plenty of company. Almost all of them were comic book related in some way. The Kirbys were often at our place, and Roz and Harriet got along very well. About that time Jack and Roz had their second child, Neil, so the kids were often playing together. Ben Oda brought Nishi over, and we had a friend named Bernie Fliegel who frequently brought along his son, Dorian.

Ken Riley would visit, but his visits were more than social.

Ken’s career as an illustrator had really taken off. Top publications from The Saturday Evening Post to National Geographic were clamoring for his work. But like the old days, the magazines still demanded that the artist send in photographic reference with the paintings. So Ken would come over and we would all get into whatever costumes were needed. We would pose for photographs which Ken would submit to the art directors. I set up a darkroom in the basement, which meant we could develop the photos on the spot. It helped Ken out, cost a lot less than a professional photo studio, and it was great fun.

There was one time when Ken had me lie in a plastic sun chair wearing my bathing suit. By the time he was done, I was an amateur astronomer reclining in a dilapidated treehouse with a telescope in my lap. My only company was an opossum. That one was definitely for The Saturday Evening Post. I know that because Ken gave it to my daughter Gail, and it has the “Curtis” stamp on the back, identifying the publisher.

A few years later we did the very same thing for Jack Davis, the artist who became famous through his work for EC Comics. I took a Springfield rifle and crouched on the ground behind a rock. The next thing you knew Jack’s pencil had transformed me into a cowboy or a Confederate soldier fighting in the Civil War.

My problem was that I liked to work at home, but at Crestwood, I had this office full of people coming in every day, and I had to keep them busy. So Jack and I had to make our way into Manhattan. We’d commute by train, drive, or ride with one of our friends. Often it was Bernie Fliegel, the legal eagle, who did the driving. Bernie was a lawyer who had been in the Army. When he got out he bought the house a couple of doors up the street from us. Bernie was also an ex-basketball player who had been an All-American center for The City College of New York. Bernie had an office in Manhattan, and one of his clients was a group of very successful black singers. They owned a limousine large enough to hold all of them, but they only used it occasionally. So Bernie kept the limo at his place, and he’d use it to drive us all into the city.

We’d all take turns driving — all except Kirby. The other guys would grumble about that, and I told them, “Just forget about it. He doesn’t know any better.” They didn’t know about his history of road rage, and it was just as well.

Despite the problems we’d run into with Stuntman and Boy Explorers, I remained close to Alfred Harvey, and would work with him on and off for much of my career. I was even godfather to his youngest son, Eric. He always knew he could count on me, and I felt the same about him. So it was only natural that I would offer him one of the best things ever to come out of the Simon and Kirby Studio.

There is a 1938 movie called Boys Town, starring Spencer Tracy as Father Flanagan, a Catholic priest who builds a home for boys in trouble. Mickey Rooney plays one of those boys. The movie was based on a real place in Omaha, Nebraska, and there was a real Father Flanagan. Few people remember that there was also a Boys Ranch, built by a steel tycoon in New Mexico during World War II. It had the same mission.

I don’t recall being aware of the ranch down in New Mexico, but I do remember always being fascinated with westerns. As a kid I used to go to the Saturday matinee movies whenever I could. Tom Mix was my favorite actor. My first comic book story was a western, and I had always loved everything that had to do with horses, from Forest Park to the Coast Guard shore patrol. Kirby didn’t ride — I think he only tried it once, and regretted it — but he had produced features like “Wilton of the West” and “Lightnin’ and the Lone Rider.” Put that together with Young Allies and our other kid gangs, and it was inevitable that we would come up with The Kid Cowboys of Boys’ Ranch.

The series had a great cast: Dandy, an orphan who had survived the Civil War, Wabash, the hillbilly with his gran’pappy’s rifle, and Angel. The latter was my favorite, with the looks of an angel, but a quick temper and a quicker draw. He shot first and asked questions later. Located near the Old West town of Four Massacres, the ranch was run by Clay Duncan, an Indian scout and the book’s answer to Father Flanagan — but with a rifle. Wee Willie Weehawken was the cook and comic relief.

If you asked either Jack or me what our favorite series was, there’s a good chance you got the answer “Boys’ Ranch.” We put everything we had into it — action and gunplay, beautiful full-page pin-ups and double-page vistas. Mort Meskin joined us on the art, and did a spectacular job. We had backup features by Ken Riley, John Severin, and Marvin Stein, like “How to Spin a Rope” and “How to Ride a Horse.” Years after the comic book ended, we cut a deal with Marvel Comics to reprint the entire series in a beautiful hardcover book.

I was up at Marvel one time, and was approached by a young woman.

“Are you Mr. Simon?” she asked.

“That’s me,” I said.

She introduced herself as someone who worked in the production department.

“I just wanted to thank you,” she said. “I read your book Boys’ Ranch, and really enjoyed it. Especially those lessons for riding a horse. I went out and tried them.”

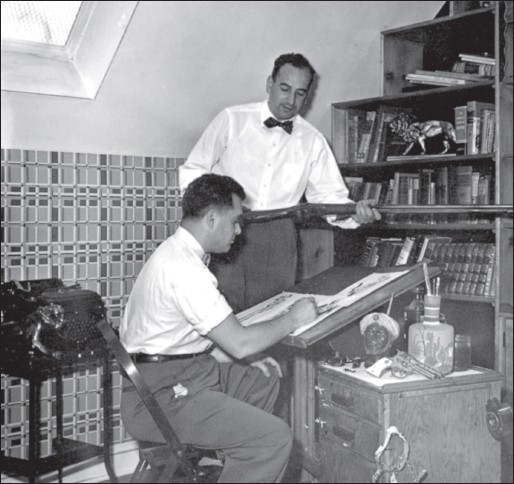

Jack and I did a lot of the Boys’ Ranch work in our studios on Long Island. Note the pistol and the spurs hanging from the taboret.

That worried me, but she had said “thank you.”

“How did that work out?” I asked cautiously. “Did you have a good time?”

“It was great,” she replied, much to my relief. “Everything worked exactly as it was supposed to.”

Unfortunately, when the series first came out, it wasn’t as much of a hit with the audience. Sales were lackluster, and we only released six issues.

A short time after the end of Boys’ Ranch, however, Alfred came back to us with one of the strangest proposals he would ever make. It was for Captain 3-D.

“Stereoscopic” photographs had been around since long before I was born, and the first 3-D movie had been released back in the 1920s, but nothing much came of the process until the motion picture Bwana Devil appeared in theaters in 1952, followed by House of Wax in 1953. Suddenly we had a craze. St. John Publications jumped on the bandwagon with a Mighty Mouse comic book, which was a huge success. They followed it with Joe Kubert’s dinosaur book, Tor. About the same time someone brought Harvey Comics a 3-D process that involved drawing the artwork on layers of acetate — an extremely labor-intensive proposition. Alfred knew he had to produce something quickly, so he called us. He offered good money, and we took a shot at it.

Kirby penciled the entire comic book. The inking was split between me, Mort Meskin, and Steve Ditko — this was mid-1953, right when we had Steve doing his Black Magic stories. The project was exhausting, and took a couple of weeks of around-the-clock effort to complete. Nevertheless, we launched right into a second issue, which Mort was going to pencil.

But before the first issue even hit the newsstands, the craze was over. Returns came in, and they were huge.

After the fact, a lawyer for EC Comics contacted Alfred. They claimed that the guy who had brought in the 3-D process had stolen it from Bill Gaines. Apparently they could prove it by comparing our books with their process. Harvey received that tried-and-true legal favorite, a cease-and-desist letter demanding that they stop publishing 3-D comics. Al was only too happy to oblige.

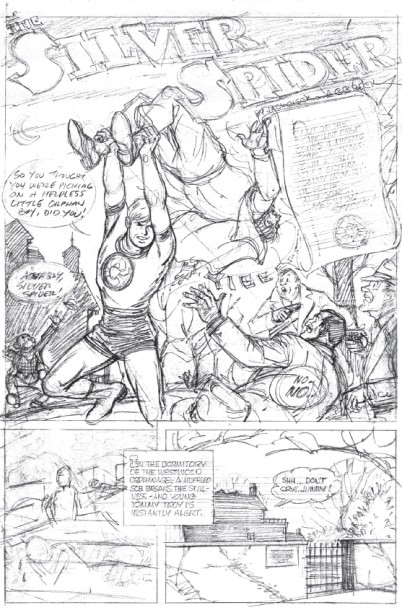

We proposed another superhero project to Alfred, as well. At first I called it “Spiderman,” and I planned to turn it over to writer Jack Oleck and artist C.C. Beck. Jack Oleck was my brother-in-law, having married Harriet’s sister Dorothy. He was one of the best and most prolific writers on the Crestwood titles. Beck was most famous as the artist on Fawcett’s Captain Marvel. Despite the work Jack and I did on Captain Marvel Adventures, and my participation in the DC-Fawcett trial, he and I didn’t meet until he contacted me in 1953.

Oleck and I ran through some story ideas, and I asked him to take a shot at a script. When he brought it back, I had some reservations about the character’s name, and changed it to The Silver Spider. Beck took the script and penciled a number of pages, and those are what we sent to Harvey. The materials were given to a young editor named Sid Jacobson, who recommended that they pass on the project. They did and I retrieved the pages.

In the 1950s, Congress was looking for communists under every bed. At the same time, they were searching for delinquents and deviants in the pages of the comics.

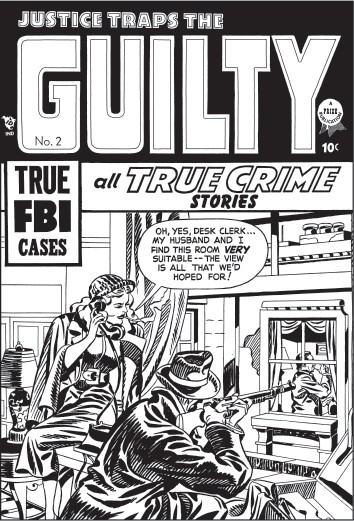

It started when the Senate launched an investigation into organized crime. That was in 1950, and the investigating committee was headed by Carey Estes Kefauver of Tennessee. The hearings were televised in living black-and-white on early television. They were so popular that Kefauver became a celebrity in his own right, appearing on the game show What’s My Line. Many of his witnesses were the sort of guys who were appearing in Headline and Justice Traps the Guilty — mobsters like Frank Costello, head of the Luciano crime family.

Then in 1954, Kefauver was a member of the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency. Even though Senator Robert Hendrickson of New Jersey was the chairman, it was called the Kefauver Committee. By this time I was living in Old Westbury, Long Island. Our first daughter had been born on June 28, 1953, so she wasn’t even a year old. Harriet and I sat in front of the television with the Kirbys and some other friends, watching the proceedings as they played out like a bad dream.

Wednesday, April 21, 1954 was the first day of the hearings. (All of the testimony you see here is exactly as it appears online.) Dr. Fredric Wertham was called to testify. He was a psychiatrist who had written a book called Seduction of the Innocent that supposedly established the link between comic books and juvenile delinquency. I hadn’t read it, but a lot of people had, and it was great fodder for the newspapers. That book was the thing that had prompted the government to hold the hearings in the first place.

First Wertham had to identify the enemy.

“We have come to the conclusion that crime comic books are comic books that depict crime,” he said, belaboring the obvious. “And we have found that it makes no difference whether the locale is western, or Superman or space ship or horror, if a girl is raped she is raped whether it is in a space ship or on the prairie.”

He went on to say, “As long as the crime comic books industry exists in its present forms there are no secure homes.”

In his testimony, he was very specific about the effects of comics on children.

“Now, as far as the effects on juvenile delinquency are concerned, we distinguish four groups of delinquency,” he said. “Delinquencies against property; delinquency associated with violence; offenses connected with sex; and then miscellaneous, consisting of fire setting, drug addiction, and childhood prostitution.”

Wertham had one theory that was particularly bizarre.

“I would like to point out to you one other crime comic book which we have found to be particularly injurious to the ethical development of children, and those are the Superman comic books. They arouse in children fantasies of sadistic joy in seeing other people punished over and over again while you yourself remain immune. We have called it the Superman complex,” he explained. “In these comic books the crime is always real and the Superman’s triumph over good is unreal. Moreover, these books, like any other, teach complete contempt of the police.”

Justice Traps the Guilty made its television debut during the Senate hearings.

As weird as it all sounded, the committee ate it up.

The worst damage, however, came from one of our own. William Gaines of EC Comics was called to testify. His books were some of the most outrageous publications of the time. Bill wasn’t equipped for this event. His testimony has become famous over the years.

He actually started out strong.

“My father was proud of the comics he published, and I am proud of the comics I publish. We use the best writers, the finest artists; we spare nothing to make each magazine, each story, each page, a work of art.”

Black Magic received special attention.

But as the questioning continued, his defenses crumbled.

Senator Kefauver held up a copy of Crime SuspenStories — the famous one.

“Here is your May 22 issue,” the senator said. “This seems to be a man with a bloody axe holding a woman’s head up which has been severed from her body. Do you think that is in good taste?”

“Yes, sir, I do, for the cover of a horror comic,” Bill replied. “A cover in bad taste, for example, might be defined as holding the head a little higher so that the neck could be seen dripping blood from it and moving the body over a little further so that the neck of the body could be seen to be bloody.”

We knew we were in trouble.

After Gaines, the comic strip artists joined the inquisition, with Milton Caniff (of Steve Canyon) and Walt Kelly (of Pogo) using the opportunity to proclaim how squeaky clean and wonderful their work was in comparison to the comic books. At one point Kelly said to the committee, “I decided I would help clean up the comic book business at one time, by introducing new features, such as folklore stories and things having to do with little boys and little animals in red and blue pants and that sort of thing.”

He went on to say about comic books, “These are not in themselves the originators of juvenile delinquency so much as juvenile delinquency is there and sometimes these are the juvenile delinquents’ handbooks.”

Unfortunately, Simon and Kirby didn’t get away unscathed. When they showed a group of the crime comics, Justice Traps the Guilty was right in the middle for everyone to see. And when Richard Clendenen, the executive director of the committee, spoke, Black Magic was singled out.

“You will note that this shot shows certain inhabitants of this sanctuary which is really a sort of sanitarium for freaks where freaks can be isolated from other persons in society,” Clendenin said. “You will note one man in the picture has two heads and four arms, another’s body extends only to the bottom of his rib. But the greatest horror of all the freaks in the sanctuary is the attractive looking girl in the center of the picture who disguises her grotesque body in a suit of foam rubber.

“The final picture shows a young doctor in the sanitarium as he sees the girl he loves without her disguise,” he continued. “The story closes as the doctor fires bullet after bullet into the girl’s misshapen body. Now, that is an example of a comic of the horror variety.”

They say, “There’s no such thing as bad publicity.” But they always forget the second half of the quote: “Except your own obituary.” For those of us sitting in front of the television, it felt more like an obituary.

At Crestwood we were being distributed by Independent News. Harold Chamberlain was Independent’s circulation director, and he responded to the comments about the various comics they distributed.

“When this first investigation came to New York... we sat down and discussed the entire matter, and it was decided at that time that we would eliminate through the news company any magazines that we felt bordered on the type that you were investigating,” he said. “We do not feel that even these magazines are the worst in the field, but they do border on your weird, fantastic group that you are investigating, and we have eliminated them and they are off the market, or will be in the next 30 days. Titles such as ‘Frankenstein,’ ‘Out of the Night,’ ‘Forbidden Worlds,’ and one which you do not have there, ‘Clutching Hand,’ have been killed.

“They no longer will be published or distributed on the newsstands.” Translation: Independent caved under pressure.

Then he continued. “In the case of Adventures Into the Unknown, the editorial content of that is to be changed to bring it entirely out of the realm of the present editorial content. The title will remain the same for the time being. They will gradually try to work the title off.” Then he got to the part we were waiting to hear. “The same holds true for Black Magic, wherein the editorial content will be changed completely.”

So, did Chamberlain ever talk to us about it?

No, he never talked to us. Never even mentioned it.

The hearings into comic books only lasted three days, April 21 and 22, and June 4. Kefauver didn’t release the findings until March 14, 1955, and by that time they were pretty much irrelevant. It’s ironic that they singled out Black Magic, since our books never had the sex and gore of the EC comics. Nevertheless, we had to deal with the fallout. At times people would come up to Harriet or Roz just to tell them how horrible comics were. They were tough enough to deal with it, and eventually things calmed down. But the industry would never again be the same.