WHEN I WORKED for the newspapers I was fascinated by the other sports cartoonists. Burris Jenkins, Jr. worked for the New York Journal-American, and did these spectacular half-page sports cartoons, as well as court and political pieces. Willard Mullin worked for the New York World-Telegram, doing some terrific boxing cartoons and creating the “Brooklyn Bum” who caricatured the Brooklyn Dodgers.

But my favorite sports writer wasn’t a cartoonist at all. It was columnist Damon Runyon, who covered the New York Giants baseball team, the professional boxing circuit, and the Saratoga racetrack. He worked for the New York American, which was a Hearst paper, and instead of just writing about the events, he wrote about the boxers, the players, the promoters, and the people who went to see the games. Since those characters inhabited the nightclubs, the speakeasies, and the betting parlors, that’s where he went for stories. He was said to be a drinker, a heavy smoker, and a womanizer.

I was completely transformed by Runyon’s stories, his essays, and books. His stories were made into Broadway plays and movies, including Guys and Dolls, and his work inspired a lot of my creations, including the Newsboy Legion, Kid Adonis, and the Duke of Broadway. I loved his characters — gamblers, hustlers, and gangsters with names like Harry the Horse, Good Time Charley, Nathan Detroit, and The Seldom Seen Kid. I loved the way he wrote.

My son Jimmy always teased me that at different times in my life I would emulate different writers too much. Damon Runyon was the first, and Jimmy accused me of copying the style of Jimmy Breslin. I did admire both of those guys, and it might be true, but what’s wrong with that?

Everybody has inspirations.

I was in a sports box at all of the events, and I stood out as being pretty young in the crowd. But all of the reporters — even the national reporters there — were very nice to me, and respected my work. I used to have front-page cartoons, and front-page bylines. So I would go to all of the events on a free ticket.

Working on a newspaper was great.

The private golf clubs would give me free access and free food — all of the perks. I’d take my friends golfing with me, on the house, and I met the boxers Primo Carnera and Joe Louis there. I was a lousy golfer, but it didn’t stop me from trying — I’ve always been very competitive. I tried my hand at tennis, too, and was shooting for a local championship when my opponent had to bow out of a tournament.

I was constantly trying new techniques on the sports cartoons.

Max Baer with Joe Simon in Speculator, NY, circa 1933.

“You’ve got to list me as the winner,” I said, “or I won’t let you bow out.”

He did.

I wasn’t the best player in my group, but I wasn’t the worst.

I also used to cover the training camp for boxers in Speculator, New York — which I always refer to as “Spectacular” — where greats like Gene Tunney, Max Schmeling, and Max Baer trained. It’s in the Adirondack Mountains, where they had an outdoor ring set up. There were cabins where the fighters lived with their families, too.

Max Baer was the fighter who was accused of killing Frankie Campbell in the ring in 1930. He used to wear the Star of David on his trunks, and claimed he was Jewish. It made sense for him to do so, since there was a substantial Jewish audience for boxing. They were big fans, and they were big customers. He also defeated Max Schmeling — Hitler’s favorite — in 1933. They claim that while he was punching Schmeling, he said, “That one’s for Hitler,” and that made him even more popular. Baer knocked Schmeling out in the tenth round.

Baer once brought me into his cabin in Speculator. He had just married this woman, Mary Ellen Sullivan, and she was there. So were his parents. They were very nice, and treated me so well. I brought Abe Levitt with me — you know, like high school guys bringing their pals along — and after we left I said to Abe, “This guy’s not Jewish — he’s Irish as Irish can be.” But we never verified that, and he was inducted into the Jewish Sports Hall of Fame in 2009.

Baer went on to star in movies like The Prizefighter and the Lady and on his own TV variety show. His younger brother, Buddy, was also one of the boxing greats. Max’s son, Max Baer, Jr., played Jethro Bodine in the television show The Beverly Hillbillies, and went on to write, produce, and direct motion pictures.

When I went to Speculator, I always carried a big twin-lens 4×5 reflex camera, the kind where you looked down into the viewfinder. I remember once I went to the ringside. There was a very nice feeling in the air — the sun was shining down (it was outdoors) and Baer was in the ring, bouncing around on these inflated balls with his stomach rolling to keep his abs tight. He saw me with the camera, called me over, and stood in front of it in a dramatic pose, and I took the picture.

That shot was beautiful. It was perfect, with all that sun helping light up the ring.

That was when I met Damon Runyon.

Runyon was there as a writer for the New York American, and when he saw me take the picture he called me over.

“You’re with Hearst, right? With the Journal?”

I said that I was, and he wrote down his name and asked me to send the picture to him, in New York.

Back then we would “wire” art and halftones to the Hearst flagship newspaper — it was like a fax machine, but the material was transmitted via an electromagnetic wave sent through a wire. The affiliate newspapers would pick up things we had produced if they were interested. They would send us stuff that they wanted us to print in our newspapers, or things we had requested.

So I sent the photo, and then the head editorial writer for the American used it to illustrate his column. The story he wrote was that Baer was “Posing like the great fighters and champions of old — but don’t get us wrong. He’s a bum.” The photo took up half of a page, and they credited it to the Rochester Journal-American.

The publisher of the Journal-American called me in. He had a reputation for being a mean son of a bitch, and I thought I was going to get a dressing down. I’m going to get fired for taking the camera out, I thought to myself.

But he surprised me.

“Congratulations on this picture getting to Hearst,” he said. “It gives us a great deal of credit. You did a great job, Simon.”

That may have been my finest hour. And I actually got to meet my idol, Damon Runyon. He was just a regular guy, and I loved his work, and he treated me like, y’know, just one of his business associates.

It was my shining moment.

I think my artwork helped my photography more than the photography helped my artwork. Yet when I was doing the sports cartoons, I observed how the body moved. If you look at the athletes in those drawings, they all have the superhero type of body. That experience had a profound effect on my layouts when I got into comic books.

After two years of working at the Rochester Journal-American, I received a job offer from the Syracuse Herald. They had heard about me. Retouching and layout work was a very special job, and there weren’t a lot of people who could do it. Even fewer had the kind of experience I had accumulated. I was offered $45 a week plus moving expenses.

So I said goodbye to Adolph and drove to Syracuse, NY, 90 miles east.

I was 20 years old.

The Syracuse Herald was an independent newspaper, competition for Hearst’s Syracuse American. I was hired to do exactly what I had done in Rochester.

On my first day at the Herald I was confronted by a young man about my age. He was dressed in a neat, dark, well-pressed suit with pointed black shoes and white spats. He appeared in the art department where I was working, and beckoned me to step into “his office.” He sat back in a leather chair, looked me up and down, and picked up a pen. Then he started scratching on a sheet of typing paper, looking very official.

“I’m James Miller,” he said, his expression serious. “Tell me something about yourself...”

Great, I thought. Another interview.

This went on for a few minutes, then loud shouts emanated from the city room, interrupting our conversation.

“Boy! Boy!”

James Miller dropped his pen and bolted out the door. I moved to the doorway and watched as a rewrite man thrust some typed pages into his hands.

“Where the hell you been, Jimmy?” the man growled. “We’re going to press in half an hour.” On his way to the pressroom, Jimmy passed me, grinning sheepishly. He was the copy boy!

Jimmy and I became close friends — he was my best friend at the Herald. Years later, when I applied for the editor position at Fox Comics, Jimmy contacted Victor Fox and claimed to be a newspaper executive. He gave me a glowing recommendation, and I got the job. I’ve forgiven him for that.

Drawing athletes prepared me for drawing superheroes.

He and I would pal around together, and go out on double dates, but I don’t think the girls liked me very much. I was in my early twenties; I had my own car and my own apartment for the first time. I had some romances and some unrequited love affairs, but the girls didn’t even know about those. I was too shy, too reserved. I don’t think they thought I was shy, but I was. I think when I went up to a girl she would think that I was with somebody else, or it seemed like I just didn’t have the confidence. I think if I had to do it over again I would exude confidence. That’s something you learn too late in life.

Tragically, Jimmy was killed in World War II. I think they have a veteran’s post named after him somewhere.

A night on the town in Syracuse, with Jimmy Miller (second from the left) and Joe Simon (center).

The Herald had a sports editor named Bob Kenefick who was a fixture in that town, a Harvard graduate and a celebrity who had been at the job for a long time. He thought I was great, I thought he was great, and we had a very good relationship between us — he used to send me out to those boxing matches, and got me beat up. He was an older man, and had a son about my age — a ne’er-do-well who stole a city bus once, and went driving around town with it. Despite things like that, I liked the kid.

We had football stars at Syracuse University, like Marty Glickman, who was a helluva runner on the football team, the Orangemen — an All-American as well as a track star. He was the guy they kicked off the 1936 Olympic team because they were playing in Berlin, in Nazi Germany, and Hitler didn’t want any Jews. Glickman and Sam Stoller were the only two Jews on the track and field team that went to Berlin, and at the last minute they were replaced — Glickman by Jesse Owens.

Owens is supposed to have objected.

“Coach, I have won my three gold medals,” he’s supposed to have said. “I have won the races I set out to win. I’ve had it. I am tired. Let Marty and Sam run. They deserve it.”

But the coach wouldn’t listen, Jesse Owens ran, and the United States team won with a world record time.

Syracuse was one of the first colleges to include black players on their football teams. We had a guy named Wilmeth Sidat-Singh. His parents were African American, but when his father died his mother married a medical student from India who adopted him and gave him his last name. Most of the time people assumed Wilmeth was Indian, but guys used to walk around the dressing room and say, “Hey, don’t say anything, but this guy’s from Harlem.” So we had one of the first black guys in college football at the time, and he was a terrific, terrific player.

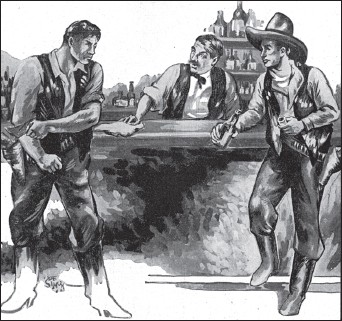

In addition to the sports work, I did courtroom drawings and I covered the court stories. I did a lot of political cartoons, and even story illustrations. Newspapers ran fiction in the Sunday editions, and I used to read the stories and give them illustrations. I did everything — I was the whole damn art department.

In Syracuse, however, I got a little smart at the time, like somebody grew a brain in me, and I began getting work from the advertising department. The advertising paid a lot more money than the editorial departments, and they didn’t have the commercial illustrators available like they did in New York, where you could just go through the yellow pages and pick one out. It wasn’t as interesting, drawing pots and pans and hidden garages and stuff like that, but I was paid by the illustration, and for each one I got more than I’d make in a week in the editorial department.

Fiction in the newspaper gave me the chance to try something different.

In the 1990s, there was a court case to decide whether or not I would be able to reclaim the rights to Simon and Kirby’s greatest character, Captain America. The proceedings involved a lot of questions, and the first one they asked when they sat me down was, “Did you go to college?”

My answer was, “No.” I was going to say, “Not really,” but I figured that would bring a torrent of other questions, and shrieks from the lawyers on both sides as they tried to figure out what I meant by that.

I never told people that I went to college. Jack Kirby used to tell everybody that I went to college, and then other people would pick it up. I’ve read where both Kirby and Stan Lee say, “Joe Simon came in, wearing a suit, and he was educated.” Those guys actually have more education than I do, but I did very, very well in high school. I say that if you came out of high school when I did, you learned more than you do in college today.

Of course, I couldn’t lie about it. I got my first job when I was 18 years old.

“No, I didn’t go to college,” I said.

What happened was that when I was in Syracuse, I used to go to Syracuse University to take some evening classes in life drawing — the kind that had live models. The guys who ran those classes knew who I was because of my cartoons in the Syracuse papers, and they asked me to lecture there.

So the point is, I didn’t go to college, but I taught at college. Nevertheless, I didn’t want to get into all of that nonsense in the deposition.

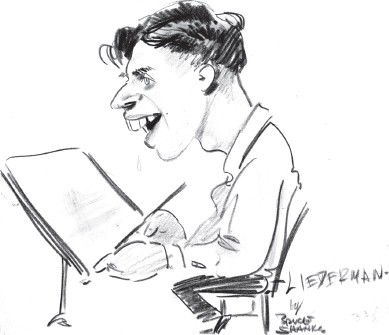

Al Liederman was in Syracuse, too, working for Hearst’s Syracuse Journal-Telegram and the Sunday paper the American. We were friendly rivals, competing to outdo each other with editorial and sports cartoons. While Al was still bloody but unbowed in the ring, I thought I could be a good match for him in print. But the competition didn’t last long, because Al received a telegram from Bruce Shanks, one of the nation’s leading editorial cartoonists, who offered Al a job at the Buffalo Evening News.

So it was like a game of musical chairs when the Syracuse Journal-Telegram offered me Al Liederman’s job at $65 a week. I accepted without hesitation, and in 1937 I was back in the Hearst stable.

Al Liederman, the Fighting Cartoonist, caricatured by Bruce Shanks.

That was where I met someone with whom I would have a decades-long relationship. One in which I would work for him, then he would work for me, then I would work for him, and so on. Martin Burstein was the police correspondent for the Journal-Telegram, stationed at police headquarters. He was one of the guys who graduated from the Syracuse University Forestry School, and he got a job for the newspaper. He loved that work.

Marty also told me he was a photographer, but he was a lousy photographer. To establish this claim, he had bought a 5×7 Speed Graphic, the same camera used by the news photographers. He told me that when he had applied for the job, he had toted the camera with him, along with a large leather-covered wooden camera case slung over his shoulder. The case was filled with film holders, flashguns, and other items that gave him the appearance of being a photographer.

It must have been convincing, because somehow he got the job. Once he was hired, though, all Marty needed to do was learn how to use the camera, and learn how to be a police reporter. To cover his ass, he would come to me with the worst pictures he had taken.

“Joe save my life,” he would say. “Retouch this, fix it up. I can’t turn it in this way.” And I would take out my airbrush and work on the photo, adding contrast and detail, until it was acceptable. I couldn’t make them good, but I could keep them from being rejected.

Marty was five-feet-ten-inches and heavyset, with a head of thick brown curly hair. He and I decided to get an apartment together, and he found one near the Syracuse University campus. The setting was ideal — there was a bar across the street that was frequented by students. But we weren’t entirely comfortable.

You see, we were about the same age as the kids who surrounded us, yet we were newspaper professionals. We didn’t want people to think we were just students, so we had to find something that would set us apart.

“We should hire Jamason,” he said.

Jamason (spelled with an “a”) was a 17-year-old delivery boy for the neighborhood grocery store. He often bragged to us that he was an excellent short order cook, and his specialty was soul food. (Not that we knew what that was.) So Marty told him about our idea, and Jamason took the job with delight. We had two stipulations, however: He had to tell all of the co-eds that he was our butler. And he had to dress like a butler. (He never managed to get the uniform right.)

For $10 a week Jamason cooked our meals. With lots of rice and meat and strange vegetables, the food was spicy and delicious. His duties included taking our clothes to the Chinese laundry down the street, and shopping for groceries and supplies. However, he wasn’t just taking the laundry out — he was taking it home, along with the food and sundries with which we had entrusted him to fill our cupboards.

Jamason (along with his “a”) was quickly dismissed.

As a police reporter, Marty often phoned his stories in. That was fortunate for him, since they then fell into the hands of a rewrite man — someone who could make certain they were readable. Reporters in those days rode along with the police in their squad cars, and occasionally there was action. This allowed Marty to play up his image as a man of mystery, and he made the most of it by dressing like James Cagney or Humphrey Bogart. He became a celebrated character at the precinct, where the cops all wanted him to write about them.

He also took every opportunity to write stories about politicians. They were all Republicans, since Syracuse was distinctly “red state” territory, and that would serve him well later on.

Marty also was best friends with Michael Stern, a steady writer for the detective magazines — the ones that featured “true crime” stories. They were buddies at Syracuse University, after which Michael had written for the New York Journal in New York City, then for the Middletown Times Herald in Middletown, NY. Michael also worked for a while in the district attorney’s office in Kings County in Brooklyn, where he was part of a prostitution investigation (and conviction) that he used in one of his books. He also wrote for Macfadden magazines. His work appeared regularly in titles like True Detective Mysteries. Little did I know that just a couple of years down the road I would do a lot of work for magazines like that.

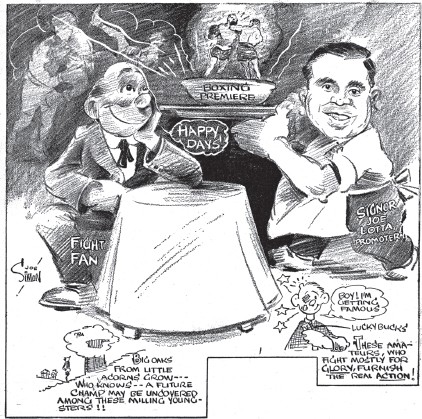

STEALING ALL-AMERICAN SPOTLIGHT.. By Joe Simon

A cartoon for the Syracuse American.

The three of us were close. Both of them appreciated what I did, and I was fascinated by what they did, too.

When Al Liederman moved to the Buffalo Evening News and I moved into his spot at the Syracuse Journal-Telegram, it felt like I was rapidly climbing to fortune and fame. However, my jubilation was to be short-lived. Radio was coming in, and taking a lot of the advertising dollars away from newspapers, a lot like the situation today with the Internet. Newspapers staggered from the loss of revenue and we learned a new word — attrition.

William Randolph Hearst had tried to run for president, he had been screwing around with the actress Marion Davies, and he had built the Hearst Castle in San Simeon, California, but the Great Depression hit him hard. He was suffering from financial reversals, and his empire was crumbling. By 1937 he had to shut down his motion picture company, sell some of his art collection, and close a bunch of newspapers.

We were saddened to learn that the Rochester Evening Journal had shut down and, soon after, we were devastated when the Newhouse chain came to Syracuse, bought out the three local dailies, and consolidated them into one morning and one afternoon paper. The Syracuse Journal-Telegram closed its printing plant.

I was out of a job.