SCIENCE brings about strange revolutions. Already, I suspect, that Thunder and Lightning in Poetry are in danger of becoming School-boyisms, like Phoebus and the Chariot of the Sun. The once tremendous celestial super-human force of Thunder, is audible not beyond 20 miles: the Evening Gun of George Town in Demerara is often heard at lake Batave on the west coast of Essequibo, a distance of about 40 miles, while the explosions during the volcanic eruption of Mount Soufrière were heard at the distance of from 6 to 700 miles.

Yet these changes as they ought not, so they do not, lessen our sense of the Sublime in the Works of the great Poets who wrote under another scheme of Beliefs and Associations—the Psalms for instance. But this supplies no ground of sanction for the repetition of the same—by poets of our times. They would ignorantly copy the sentences, when they ought to have imitated the Poet, and consequently, have composed, as he composed, in the light and with assurance of the Sympathy, of the Age, of which he was the Blossom. The vehement Belief of the Devil and his numberless Army of Rebel Angels was Heroism in Luther—a pitiful anility in Mr. Wilberforce.

MS.

Ideas may become as vivid and distinct, and the feelings accompanying them as vivid, as original impressions. And this may finally make a man independent of his Senses. One use of poetry.

MS.

Solomon’s Song. There was a time when I thought scorn of this charming Idyll, this prototype of whatever is most beautiful and affecting in Theocritus … and (as far as the few precious fragments allow the conjecture) in Sappho, having a spiritual Sense—in being more than an epithalamium on Solomon’s Marriage with a Princess of Egypt. But the more extensive my acquaintance has become with the Persian Poets—and the more attentively I have studied verse by verse the Song itself, and sought either to discover a plan and purpose in the whole, or to reduce it to a series of distinct Eclogues or Idylls—the more disposed I find myself to adopt the contrary judgement. The analogous passages in several of the Prophets, especially Isaiah Ch. V, and the Fact, that the Jewish Church before the Birth of Christ interpreted it spiritually, and that Rabbinical Comments which if not themselves of so high antiquity are evidently transcripts or echoes of Teachers before or contemporary with Christ, are in existence and (for we cannot suppose them to have borrowed a hated faith from the hated Christians) demonstrate what indeed Paul’s writings seem to me already to prove, that a Spiritual Conception of the Messiah, and of his Communion with the Soul, was entertained by some at least of the Doctors between the Return from the Captivity and the Birth of our Lord. In fact, the lovely Allegory of Cupid and Psyche shews that the Idea was spread among the Gentiles.

MS.

It is quite wonderful that Luther who could see so plainly that Judith was an Allegoric Poem should have been blind to the Book of Jonas being an Apologue, in which Jonas means the Israelitesh nation!

MS.

To perceive and feel the Beautiful, the Pathetic, and the Sublime in Nature, in Thought, or in Action—this combined with the power of conveying such Perceptions and Feelings to the minds and hearts of others under the most pleasurable Forms of Eye and Ear—this is poetic Genius. A gift of Heaven confined to no one Race or Period, a ray which penetrates to the Savage [man crossed out] in the [distant recesses of unplanted Forests crossed out] depth of Wildernesses, and throws a nobler Light, a glory beyond its own, on the splendor of the Palaces. [If then there exists no monopoly of poetry as little can there exist crossed out.] If then Poetry itself be a free and vital power which never wholly deserts any age or Nation unless it have previously deserted itself, [and abandoned its own best privilege, that of fighting up against the hourly influences of Custom and the pressure of anxieties without Love crossed out] that Criticism, which would bind it down to any one Model, and bid it grow in a mould is a mere Despotism of False Taste, [a usurpation of empty [Forms crossed out] Rules over Life and Substance] and would reduce all modern Genius to a state which (if it were not too ludicrous) might be justly compared to that of the Soldier Crabs on the Tropical Islands, which wander naked and imperfect till they creep into the cast off Shells of a nobler Race.

To counteract this Disease of long-civilized Societies, and to establish not only the identity of the Essence under the greatest variety of Forms, but the congruity and even the necessity of that variety, is the common end and aim of the present Course.

… Beauty, Majesty, Grace and Perspicuity, and before the Harmony we have described came to its perfection, Vehemence and Impetuosity—these are the constituents of the Greek Drama—and the great Rule was the separation, or the removal, of the Heterogeneous—even as the Spirit of the Romantic Poetry, is modification, or the blending of the Heterogeneous into an Whole by the Unity of the Effect. Such were the deeper and essential contra-distinctions—and to these we must add the more accidental circumstances, from the origin of the Drama, and the size, arrangement, and object of the Theatres.

MS.

Memoranda for a History of English Poetry, biographical, bibliographical, critical and philosophical, in distinct Essays—

1. English Romances—compared with the Latin Hexameter Romance on Attila—with the German metrical Romances &c.

2. Chaucer—illustrated by the Minnesänger, and as in all that follow an endeavour to ascertain, first, the degree and sort of the merit of the Poems comprized in his Works, and secondly, what and how much of this belonged strictly et sibi proprium to Chaucer himself, what must be given to his Contemporaries, and Predecessors. This will be abundantly inore interesting in Shakespere; yet interesting and necessary to a philosophical Critic in all.

3. Spenser—with connecting Introductions.

4. English Ballads, illustrated by the Translations of the Volkslieder of all countries.—Ossian—Welsh Poets—. Series of true heroic Ballads from Ossian.

7. Dryden and the History of the witty Logicians, Butler (ought he not to have a distinct tho’ short Essay?)—B. Johnson, Donne, Cowley Pope.—

8. Modern Poetry… with introductory (or annexes?) Characters of Cowper, Burns, Thomson, Collins, Akenside, and any real poet, quod real poet, and exclusively confined to their own. Faults and Excellencies.—To conclude with a philosophical Analysis of Poetry, nempe ens=bonum, and the fountains of its pleasures in the Nature of Man: and of the pain and disgust with which it may affect men in a vitiated state of Thought and Feeling; tho’ this will have been probably anticipated in the former Essay, Modern Poetry, i.e. Poetry=Not-poetry, ut lucus a non lucendo, and mons a non movendo, and its badness i.e. impermanence demonstrated, and the sources detected of the pain known to the wise and of the pleasure to the pleasures to the corrupted—illustrated by a History of bad Poetry in all ages of our Literature.——

Milton carefully compared and contrasted with Jerome [sic] Taylor—and on occasion perhaps of his Controversy with Hall introduce a philosophical Abstract of the History of English Prose—if only to cut Dr. J. ‘to the Liver.’.1

MS.

The heroic verse of the Italians has been regarded by all Grammarians and Lexicographers hitherto as Paniambic according to its Rule; the deviations from which are to be considered as poetic Licenses, or as Discords introduced into Harmony for Variety or particular Effect. In technical Language we are to describe it as Pan-iambic pentameter hyperacetalectic, in other words (and for those who have no passion for polysyllables or Greek compounds) we are, it seems, to deem the heroic Verse of Dante and Ariosto, as composed of five Iambics, the fifth having a superabundant unaccented Syllable. If this statement be indeed the true one, the loftiest and most learned Italians are licentious beyond all modern precedent, and even among the ancients, who can furnish no legitimate Authority to us, who do not, as they did, weigh our [metres crossed out] verses by any conscious attention to Quantity, who count them by the Beat, Pulse, or Accent—yet even among the ancients we shall scarcely find any instance of equal licentiousness, except in the loose Iambics of Latin Comedy, the metre [of] which forms the connecting Link between Verse and the Prose of lively conversation, both the pleasure of which, and the cause of the pleasure, were to be felt, not noticed.

It is indeed curious to observe the Prosody invented by the Grammar-writers in order to reduce the Italian Verses to the Possibility of Iambic movement, a Prosody so perfectly arbitrary that whoever read a page of Ariosto according to it would be almost as unintelligible to an Italian, as if he had been reading Chinese. ‘Suo’, for instance, and ‘pria’, except at the end of a Line, form but one syllable, and tho’ it is admitted on all sides, that in fact the former always is two Syllables, and the latter cannot ever be pronounced otherwise than as two. True! it is answered—But such Dissyllables count only as one—a reply, which appears to me to mean neither more or less than this: It is not so, but according to the assertion of Grammarians, it ought to be so. In like manner, the whole doctrine of Elisions, except in the few instances in the Italian in which they actually occur and which in their Poetry are always noted in accurate Printing by the omission of the vowel and by an Apostrophe, is utterly hollow, and borrowed from the Ancient Versification by Quantity, by men of whom it is [not crossed out and no more unkind than unjust substituted] to say [more unkind than unjust to say?] that they had great and various Learning, but that their Skulls were Magazines, not Manufacturies, much less fields or gardens; Magazines sufficiently under the power of their Memory, and wholly undisturbed by any action of philosophic Thought. What indeed can be more incongruous than to admit that in one instance a Vowel shall not be pronounced at all, that in another a Vowel shall be distinctly pronounced, and yet that the latter is to count for as complete a nothing as the actually non-existent former? If this System could be proved false, not only by its inherent Absurdity but by the substitution of a rational System, I deem it more than probable that a nobler, a freer and more powerful Versification (the great menstruum and vehicle of poetic thought and feeling) would gradually [obtain in crossed out] win its way in Europe; and then we should feel how much [fragment incomplete].

[f. 52 may or may not be a continuation off 51.] How small effect faults have where there are great Beauties—but then of Beauties there are two senses. 1. mere scattered passages which being selected all is a Caput Mortuum—this can render a book valuable to literary men and to the curious in collection, and when a selection has been made and published, not even to them. [2]. But when the Beauties are diffused all over, when the faults as in Milton are only omittable passages—or at best a small part of the Plan—nay, even when they are woven thro’ warp and woof, if the Beauties are the same, and in a greater degree—perhaps if even in the same—yet the Book becomes a darling, and we scarcely think of the faults, except as pleasing us less, rather than displeasing.

MS.

The elder Languages fitter for Poetry because they expressed only prominent ideas with clearness, others but darkly——Therefore the French wholly unfit for Poetry; because [all] is clear in their Language, i.e. Feelings created by obscure ideas associate themselves with the one clear idea. When no criticism is pretended to, and the Mind in its simplicity gives itself up to a Poem as to a work of nature, Poetry gives most pleasure when only generally and not perfectly understood. It was so by me with Gray’s Bard, and Collins’ odes. The Bard once intoxicated me, and now I read it without pleasure. From this cause it is that what I call metaphysical Poetry gives me so much delight.

MS.

1. Concerning the comparative merit of the present generation (which we would extend to the last 40 or 50 years) and of the preceding period from the Revolution, in point of Genius or productive power, opinions may differ. But we think, that in point of Taste in the Fine Arts, and in first principles of Criticism, which can indeed neither create a Taste or supply the want of it but yet may conduce effectively to its cultivation and are perhaps indispensable in securing it from the aberrations of caprice and fashion, there can be little doubt that we have the advantage over our Forefathers. There are, to be sure, Heretics to be met with who would reverse the position in Music, and while in Haydn, Mozart, Cimarosa, and Beethoven, as the Magnates of a whole brilliant constellation, they acknowledge the spirit of Apollo, find in the multitude of musical Critics and dilettanti performers only the ears* and the taste of Midas. However, exceptio probat regulam, and in truth our present purpose would be answered, tho’ the position of our superior Taste were Taste in the appreciation of Poetry or even to yet narrower limits, the art of Poetry, or the requisite perfections of a Poem. But in proof of this, it might be sufficient to recall the Judgements of Critics of highest name and authority, who had formed their taste in that School, on which the Wartons first adventured a timorous attack, the censure so neutralized by compliments and half-retractions, that it might remind one of a Wasp staggering out of a Honey Pot, with both wing and sting sheathed in the clammy sweetness.

What should we think of a Critic of the present day, who instituting a comparison between the Latin Poems of Milton and Cowley to the advantage of the latter, should gravely assert, that ‘Cowley without much loss of purity or elegance accommodates the diction of Rome to his own conceptions’. Except the collections of the Italian Latinists of the 15th Century, it would not be easy to name any equal number of Poems by the same author that could be fairly preferred to those of Milton in classical purity on the one hand, or in weight of Thought and unborrowed imagery on the other; while for competitors in barbarism with Cowley’s Latin Poem De Plantis, or even his not quite so bad Davideid Hexameters, we must go I fear to the Deliciae Poetarum Germanorum or other [similar crossed out] Warehouses of Seal-fat, Whale Blubber and the like Boreal Confectionaries selected by the delicate Gruter.

We may question too with little risk of offence whether even the aweful name of Dr. Johnson will be powerful enough ten years hence to rescue the writer from contempt who should seriously repeat, that without knowledge of the author ‘no man could fancy that he read the Lycidas with pleasure’—that in its form it is easy, vulgar and disgusting; and in the whole poem neither nature nor art: or that the metre of the Par[adise] Lost is verse to the eye only; or that after half a century of forced thoughts and rugged metre some advances towards nature and harmony had been made by Waller and Denham; [and yet left to Dryden the honour of having first refined crossed out] yet not such as to interfere in any considerable degree with the claims of Dryden as the first who refined the language, improved the sentiments (!!) and tuned the numbers, of English Poetry; or lastly that the stanza of Prior in which two elegiac Quatrains are put atop a couplet ending with an Alexandrine, as compared with the Stanza of Spenser (that wonder-work of metrical Skill and Genius! that nearest approach to a perfect Whole, as bringing the greatest possible variety into compleat Unity by the never interrupted interdependence of the parts!—that ‘immortal Verse’, that ‘winding bout

Of linked sweetness long drawn out

Untwisting all the chains that tie

The hidden soul of Harmony’)

—that these ten-line Paragraphs into which Prior has divided his ode, and which have about the same claims to be stanzas, as the King and three Fidlers to enter solus, should not indeed have been called an imitation of the Stanza of the Fairy Queen, but had however avoided its difficulties without losing any of its powers of pleasing!

The revived attention to our elder Poets, which Percy and Garrick had perhaps equal share in awakening, the revulsion against the French Taste which was so far successful as to confine the Usurper within the natural limits of the French Language; the re-establishment of the Romantic and Italian School in Germany and G. Britain by the genius of Wieland, Goethe, Tieck, Southey, Scott, and Byron among the poets, and the Lectures of Coleridge, Schlegel, Campbell and others among the Critics; these, at once aided and corrected by the increased ardor with which the study of ancient literature and especially the Greek Poets and Dramatists, is pursued, esteemed and encouraged by the Gentry of the Country, and men of the highest rank and office, have given a spread and a fashion to predilections of higher hope and (what is still better) to principles of Preference at once more general and more just.

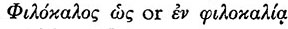

Still however this Improvement has hitherto, it must be confessed, revealed itself chiefly in the popularity acquired by those works, in which the effort to [extend and vary the measures crossed out] introduce into poetry a freer and more various scheme of Diction and Metre: as far as our own language is concerned. And with regard to the measures of the Ancients, we dare not disguise from ourselves, that the improvement is to be inferred from the tendency, as a datum of Hope rather than from any actual progress, if we may be allowed a play of words, rather by the succession than the success of the attempts, to bring the rhythm and metre of the Greek Lyrics into light and order. In the simpler forms of metre, that occur in the dramatic Dialogue, we owe to Porson all that could be achieved by an acute and exact Scholar gifted with a singular fineness of tact thoroughly at home with the [Greek crossed out] Attic Drama, and more widely and familiarly acquainted with the Lexicographers and Grammarians than any Philologist that could be said to come near him  , et cui flos nullus apud Ilissi ripas videlebatur, [sic] or something of that sort.…

, et cui flos nullus apud Ilissi ripas videlebatur, [sic] or something of that sort.…

MS.

De Boyer quotes Virgil’s panegyric on Marcellus from the Aeneid, Book VI, the 23 lines beginning:

Quis pater, ille virum qui sic comitatur euntem?

Filius, anne aliquis magna de stirpe nepotum?

Quis strepitus circa comitum! quantum instar in ipso est?

Sed nox atra caput tristi circumvolat umbra.

Turn pater Anchises lachrimis ingressus obortis.

O nate, ingentem luctum ne quaere tuorum.

Ostendent terris hunc tantum fata, neque ultra

Esse sinent. Nimium vobis Romana propago

Visa potens, superi, propria haec si dona fuissent.

Quantos ille virum magnam Mavortis ad urbem

Campus aget gemitus? Vel quae, Tyberine, videbis

Funera, cum tumulum praeterlabere recentem!

Nec puer Iliaca quisquam de gente Latinos

In tantum spe tollet avos: nec Romula quondam

Ullo se tantum tellus jactabit alumno.

Heu pietas, heu prisca fides, invictaque bello

Dextera! non illi quisquam se impune tulisset

Obvius armato: seu cum pedes iret in postem,

Seu spumantis equi foderet calcaribus armos!

Heu miserande puer! si qua fata aspera rumpas,

Tu Marcellus eris, manibus date lilia plenis:

Purpureos spargam flores, animamque nepotis.

His saltern accumulem donis et fungar inani Munere.

[Translation of J. Jackson, O.U.P., 1908.

Who is he my father, that thus attends the warrior’s path? A son, or one of the heroic strain of his children’s children? How the retinue about him murmurs praise! What majesty is in his port! Yet sable Night hovers round his head with mournful shade. Then father Anchises began, while his tears welled: ‘O my son, seek not to know the great agony of thy people! Him the fates shall but shew the earth, nor suffer longer to be. Too great in thy sight, O Heaven, the power of Rome’s children, had this thy guerdon endured! What moaning of men shall echo from the famed Field to Mavor’s queenly city! What obsequies, O Tiber, shalt thou see, when thou flowest by his new-raised grave! No child of Ilian blood shall raise his Latin ancestry so high in hope, nor ever again shall Romulus’s land so vaunt her in any that she fosters. Alas for piety, alas for old-world faith, and the land unvanquished in war! None scatheless had met his blade, whether on foot he marched against the foeman, or buried the spur in the flank of his reeking steed! Ay me, thou child of tears, if haply thou mayest burst the cruel barriers of fate, thou shalt be Marcellus! Give me lilies from laden hands; let me scatter purple blossoms, and shower these gifts—if no more—on the spirit of my child, till the barren service be so discharged.’]

Coleridge comments: That the lines are beautiful, especially in the metre and composition, singultus quasi numerorum, sobs of Harmony,—this I see and feel. But that they are wonderful, super-excellent, &c &c, I deny—for what is there that might not have been said of any other hopeful young Roman who had died in his youth—what one distinct Image? What one deep feeling that goes to the human heart? I see not one.

MS.

I take unceasing delight in Chaucer. His manly cheerfulness is especially delicious to me in my old age. How exquisitely tender he is, and yet how perfectly free from the least touch of sickly melancholy or morbid drooping! The sympathy of the poet with the subjects of his poetry is particularly remarkable in Shakespeare and Chaucer; but what the first effects by a strong act of imagination and mental metamorphosis, the last does without any effort, merely by the inborn kindly joyousness of his nature. How well we seem to know Chaucer! How absolutely nothing do we know of Shakespeare!

I cannot in the least allow any necessity for Chaucer’s poetry, especially the Canterbury Tales, being considered obsolete. Let a few plain rules be given for sounding the final è of syllables, and for expressing the termination of such words as ocean, and nation, etc. as dissyllables,—or let the syllables to be sounded in such cases be marked by a competent metrist. This simple expedient would, with a very few trifling exceptions, where the errors are inveterate, enable any reader to feel the perfect smoothness and harmony of Chaucer’s verse. As to understanding his language, if you read twenty pages with a good glossary, you surely can find no further difficulty, even as it is; but I should have no objection to see this done:—Strike out those words which are now obsolete, and I will venture to say that I will replace every one of them by words still in use out of Chaucer himself, or Gower his disciple. I don’t want this myself: I rather like to see the significant terms which Chaucer unsuccessfully offered as candidates for admission into our language; but surely so very slight a change of the text may well be pardoned, even by black-letterati, for the purpose of restoring so great a poet to his ancient and most deserved popularity.

Table Talk.

The object of Thucydides was to show the ills resulting to Greece from the separation and conflict of the spirits or elements of democracy and oligarchy. The object of Tacitus was to demonstrate the desperate consequences of the loss of liberty on the minds and hearts of men.

Table Talk.

I have already told you that in my opinion the destruction of Jerusalem is the only subject now left for an epic poem of the highest kind. Yet, with all its great capabilities, it has this one grand defect—that, whereas a poem, to be epic, must have a personal interest,—in the destruction of Jerusalem no genius or skill could possibly preserve the interest for the hero from being merged in the interest for the event. The fact is, the event itself is too sublime and overwhelming.

In my judgment, an epic poem must either be national or mundane. As to Arthur, you could not by any means make a poem on him national to Englishmen. What have we to do with him? Milton saw this, and with a judgment at least equal to his genius, took a mundane theme—one common to all mankind. His Adam and Eve are all men and women inclusively. Pope satirizes Milton for making God the Father talk like a school divine. Pope was hardly the man to criticize Milton. The truth is, the judgment of Milton in the conduct of the celestial part of his story is very exquisite. Wherever God is represented as directly acting as Creator, without any exhibition of his own essence, Milton adopts the simplest and sternest language of the Scriptures. He ventures upon no poetic diction, no amplification, no pathos, no affection. It is truly the Voice of the Word of the Lord coming to, and acting on, the subject Chaos. But, as some personal interest was demanded for the purposes of poetry, Milton takes advantage of the dramatic representation of God’s address to the Son, the Filial Alterity, and in those addresses slips in, as it were by stealth, language of affection, or thought, or sentiment. Indeed, although Milton was undoubtedly a high Arian in his mature life, he does in the necessity of poetry give a greater objectivity to the Father and the Son, than he would have justified in argument. He was very wise in adopting the strong anthropomorphism of the Hebrew Scriptures at once. Compare the Paradise Lost with Klopstock’s Messiah, and you will learn to appreciate Milton’s judgment and skill quite as much as his genius.

Table Talk.

The character and conduct of Judas would be an insolvable Enigma, if we had only the three first Gospels. The immediate Disciples of Christ seem indeed to have regarded his act and his whole proceeding with a revulsive horror which made them unwilling to speak of him more than by the hasty statement of the Fact. Even St John does but dart a gleam of Light into the obscurity of the Incident. From him we may probably infer, that Judas had permitted himself to be tampered with by the Pharisaic Faction, possibly from a strange confusion of motives of which he himself could have given no clear account—ex. gr. if he had not the power of rescuing himself, then the Pharisees were in the Right, and he was not sent by God—and his [miraculous crossed out] magical powers, according to the commonly received opinion, would not avail him after he had been once delivered into the hands of the lawful Authorities—but if he was, then this would only accelerate the open proof of his divine Power, and occasion him to display the Sign, which the Pharisees had before tempted him to give—i.e. the signal to a general insurrection against the Romans by the public declaration of his being King of the Jews. We are all too apt to forget the dark and fleshly state of all the Apostles during our Lord’s sojourn with them. What were the expectations and imaginations of the Sons of Zebedee when they were quarrelling about the places, they should hold in the new Court—Which should be the Grand Vizier? Hence the character of Judas appears to be far more incomprehensible and strange than in a fair view of all the circumstances it ought to do. But when Judas discovered that our Lord knew what had been going on within him, and the action, with which he had been dallying—then the vindictive anger of a base man unexpectedly detected, and the despair of ever recovering his Lord’s esteem and confidence—in short, a morbid chaos of bad and confused thoughts and impulses, a guilty state of somnambulism, supervened—or as St John says, Satan entered into him and he precipitated himself into Guilt as he afterward, as the sequel of the same frightful Dream flung himself headlong into Death. I object from principle to all fictions grounded on Scripture History—and more than all to any introduction of our Lord. Even the Paradise Regained offends my mind. Here what is not historic truth, is a presumptuous falsehood. But if I dared dramatize so aweful a part of the Gospel Narrative, I seem to feel that I could evolve the Judas into a perfectly intelligible character.

28 Septr 1829. Monday Night. I will not even in respect of an inward intention hastily determine on such an attempt. But after writing the preceding page it did strike me, that it might be of use and for edification to compose a sacred Drama, for the purpose of elucidating the character of Judas, and without attributing to our Lord any act or even words not authenticated by the Gospels. One advantage would be, the presenting of a consistent whole by strict adherence to the narrative of John, and availing myself of the other Gospels so far only, as they were evidently consistent and of a piece with it. The first Scene might be a Dialogue between Judas and one of the Leading Pharisees. S. T. C.

MS.

‘For one person who has remarked or praised a beautiful passage in Walter Scott’s works, a hundred have said,—“How many volumes he has written!” So of Matthews: it is not “How admirable such and such parts are!” but “It is wonderful that one man should do all this!”’

Allsop.

Reviewers resemble often the English Jury and the Italian Conclave, that they [are] incapable of eating till they have condemned or crowned.

MS.

In the Paradise Lost—indeed in every one of his poems—it is Milton himself whom you see; his Satan, his Adam, his Raphael, almost his Eve—are all John Milton; and it is a sense of this intense egotism that gives me the greatest pleasure in reading Milton’s works. The egotism of such a man is a revelation of spirit.

Table Talk.

Shakespeare is the Spinozistic deity—an omnipresent creativeness. Milton is the deity of prescience; he stands ab extra, and drives a fiery chariot and four, making the horses feel the iron curb which holds them in. Shakespear’s poetry is characterless; that is, it does not reflect the individual Shakespeare; but John Milton himself is in every line of the Paradise Lost. Shakespeare’s rhymed verses are excessively condensed,—epigrams with the point every where; but in his blank dramatic verse he is diffused, with a linked sweetness long drawn out. No one can understand Shakespeare’s superiority fully until he has ascertained, by comparison, all that which he possessed in common with several other great dramatists of his age, and has then calculated the surplus which is entirely Shakespeare’s own. His rhythm is so perfect, that you may be almost sure that you do not understand the real force of a line, if it does not run well as you read it. The necessary mental pause after every hemistich or imperfect line is always equal to the time that would have been taken in reading the complete verse.

Table Talk.

A Maxim is a conclusion upon observation of matters of fact, and is merely retrospective: an Idea, or, if you like, a Principle, carries knowledge within itself, and is prospective. Polonius is a man of maxims. Whilst he is descanting on matters of past experience, as in that excellent speech to Laertes before he sets out on his travels, he is admirable; but when he comes to advise or project, he is a mere dotard. You see, Hamlet, as the man of ideas, despises him.

Table Talk.

I have often told you that I do not think there is any jealousy, properly so called, in the character of Othello. There is no predisposition to suspicion, which I take to be an essential term in the definition of the word. Desdemona very truly told Emilia that he was not jealous, that is, of a jealous habit, and he says so as truly of himself. Iago’s suggestions, you see, are quite new to him; they do not correspond with any thing of a like nature previously in his mind. If Desdemona had, in fact, been guilty, no one would have thought of calling Othello’s conduct that of a jealous man. He could not act otherwise than he did with the lights he had; whereas jealousy can never be strictly right. See how utterly unlike Othello is to Leontes, in the Winter’s Tale, or even to Leonatus, in Cymbeline! The jealousy of the first proceeds from an evident trifle, and something like hatred is mingled with it; and the conduct of Leonatus in accepting the wager, and exposing his wife to the trial, denotes a jealous temper already formed.

Table Talk.

The difference between the products of a well-disciplined and those of an uncultivated understanding, in relation to what we will now venture to call the Science of Method, is often and admirably exhibited by our great dramatist. I scarcely need refer my readers to the Clown’s evidence, in the first scene of the second act of Measure for Measure, or to the Nurse in Romeo and Juliet. But not to leave the position, without an instance to illustrate it, I will take the ‘easy-yielding’ Mrs. Quickly’s relation of the circumstances of Sir John Falstaff’s debt to her:—

FALSTAFF. What is the gross sum that I owe thee?

HOST. Marry, if thou wert an honest man, thyself and the money too. Thou didst swear to me upon a parcel-gilt goblet, sitting in my Dolphin chamber, at the round table, by a seacoal fire, upon Wednesday in Whitsun week, when the prince broke thy head for liking his father to a singing-man of Windsor; thou didst swear to me then, as I was washing thy wound, to marry me and make me my lady thy wife. Canst thou deny it? Did not goodwife Keech, the butcher’s wife, come in then and call me gossip Quickly?—coming in to borrow a mess of vinegar; telling us she had a good dish of prawns; whereby thou didst desire to eat some; whereby I told thee they were ill for a green wound, etc. Henry IV. 1st pt. Act ii. sc. 1.

And this, be it observed, is so far from being carried beyond the bounds of a fair imitation, that ‘the poor soul’s’ thoughts and sentences are more closely interlinked than the truth of nature would have required, but that the connections and sequence, which the habit of Method can alone give, have in this instance a substitute in the fusion of passion. For the absence of Method, which characterizes the uneducated, is occasioned by an habitual submission of the understanding to mere events and images as such, and independent of any power in the mind to classify or appropriate them. The general accompaniments of time and place are the only relations which persons of this class appear to regard in their statements. As this constitutes their leading feature, the contrary excellence, as distinguishing the well-educated man, must be referred to the contrary habit. Method, therefore, becomes natural to the mind which has been accustomed to contemplate not things only, or for their own sake alone, but likewise and chiefly the relations of things, either their relations to each other, or to the observer, or to the state and apprehension of the hearers. To enumerate and analyze these relations, with the conditions under which alone they are discoverable, is to teach the science of Method.

The enviable results of this science, when knowledge has been ripened into those habits which at once secure and evince its possession, can scarcely be exhibited more forcibly as well as more pleasingly, than by contrasting with the former extract from Shakespeare the narration given by Hamlet to Horatio of the occurrences during his proposed transportation to England, and the events that interrupted his voyage:—

HAMLET. Sir, in my heart there was a kind of fighting

That would not let me sleep: methought, I lay

Worse than the mutines in the bilboes. Rashly,

And praised be rashness for it—Let us know,

Our indiscretion sometimes serves us well,

When our deep plots do fail: and that should teach us,

There’s a divinity that shapes our ends,

Rough-hew them how we will.

HOR. That is most certain.

HAM. Up from my cabin,

My sea-gown scarf’d about me, in the dark

Grop’d I to find out them; had my desire;

Finger’d their packet; and, in fine, withdrew

To my own room again; making so bold,

My fears forgetting manners, to unseal

Their grand commission; where I found, Horatio,

A royal knavery; an exact command—

Larded with many several sorts of reasons,

Importing Denmark’s health, and England’s too,

With, ho! such bugs and goblins in my life—

That on the supervise, no leisure bated,

No, not to stay the grinding of the axe,

My head should be struck off!

HOR. Is’t possible?

HAM. Here’s the commission;—read it at more leisure.

Act v. sc. 2.

Here the events, with the circumstances of time and place, are all stated with equal compression and rapidity, not one introduced which could have been omitted without injury to the intelligibility of the whole process. If any tendency is discoverable, as far as the mere facts are in question, it is the tendency to omission: and, accordingly, the reader will observe in the following quotation that the attention of the narrator is called back to one material circumstance, which he was hurrying by, by a direct question from the friend to whom the story is communicated, ‘How was this sealed?’ But by a trait which is indeed peculiarly characteristic of Hamlet’s mind, ever disposed to generalize, and meditative if to excess (but which, with due abatement and reduction, is distinctive of every powerful and methodizing intellect), all the digressions and enlargements consist of reflections, truths, and principles of general and permanent interest, either directly expressed or disguised in playful satire.

I sat me down;

Devis’d a new commission; wrote it fair.

I once did hold it, as our statists do,

A baseness to write fair, and laboured much

How to forget that learning; but, sir, now

It did me yeoman’s service. Wilt thou know

The effect of what I wrote?

HOR. Ay, good my lord.

HAM. An earnest conjuration from the king,—

As England was his faithful tributary;

As love between them, like the palm, might flourish;

As peace should still her wheaten garland wear,

And many such like As’s of great charge—

That on the view and knowing of these contents,

Without debatement further, more or less,

He should the bearers put to sudden death,

No shriving time allowed.

HOR. How was this seal’d?

HAM. Why, even in that was heaven ordinant.

I had my father’s signet in my purse,

Which was the model of the Danish seal:

Folded the writ up in the form of the other;

Subscribed it; gave’t the impression; placed it safely,

The changeling never known. Now, the next day

Was our sea-fight; and what to this was sequent,

Thou know’st already.

HOR. So Guildenstern and Rosencrantz go to’t?

HAM. Why, man, they did make love to this employment.

They are not near my conscience: their defeat

Doth by their own insinuation grow.

’Tis dangerous when the baser nature comes

Between the pass and fell incensed points

Of mighty opposites.

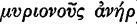

It would, perhaps, be sufficient to remark of the preceding passage, in connection with the humorous specimen of narration,

Fermenting o’er with frothy circumstance,

in Henry IV, that if, overlooking the different value of the matter in each, we considered the form alone, we should find both immethodical,—Hamlet from the excess, Mrs. Quickly from the want, of reflection and generalization; and that Method, therefore, must result from the due mean or balance between our passive impressions and the mind’s own re-action on the same. Whether this re-action do not suppose or imply a primary act positively originating in the mind itself, and prior to the object in order of nature, though co-instantaneous with it in its manifestation, will be hereafter discussed. But I had a further purpose in thus contrasting these extracts from our ‘myriad-minded bard’, ( ). We wished to bring forward, each for itself, these two elements of method, or, to adopt an arithmetical term, its two main factors.

). We wished to bring forward, each for itself, these two elements of method, or, to adopt an arithmetical term, its two main factors.

Instances of the want of generalization are of no rare occurrence in real life: and the narrations of Shakespear’s Hostess and the Tapster differ from those of the ignorant and unthinking in general by their superior humour, the poet’s own gift and infusion, not by their want of method, which is not greater than we often meet with in that class, of which they are the dramatic representatives. Instances of the opposite fault, arising from the excess of generalization and reflection in minds of the opposite class, will, like the minds themselves, occur less frequently in the course of our own personal experience.…

Thus exuberance of mind, on the one hand, interferes with the forms of Method; but sterility of mind, on the other, wanting the spring and impulse to mental action, is wholly destructive of Method itself. For in attending too exclusively to the relations which the past or passing events and objects bear to general truth, and the moods of his own thought, the most intelligent man is sometimes in danger of overlooking that other relation, in which they are likewise to be placed to the apprehension and sympathies of his hearers. His discourse appears like soliloquy intermixed with dialogue. But the uneducated and unreflecting talker overlooks all mental relations, both logical and psychological; and consequently precludes all Method that is not purely accidental. Hence the nearer the things and incidents in time and place, the more distant, disjointed, and impertinent to each other, and to any common purpose, will they appear in his narration: and this from the want of a staple, or starting-post, in the narrator himself; from the absence of the leading thought, which, borrowing a phrase from the nomenclature of legislation, I may not inaptly call the initiative. On the contrary, where the habit of Method is present and effective, things the most remote and diverse in time, place, and outward circumstance, are brought into mental contiguity and succession, the more striking as the less expected. But while I would impress the necessity of this habit, the illustrations adduced give proof that in undue preponderance, and when the prerogative of the mind is stretched into despotism, the discourse may degenerate into the grotesque or the fantastical.

With what a profound insight into the constitution of the human soul is this exhibited to us in the character of the Prince of Denmark, where flying from the sense of reality, and seeking a reprieve from the pressure of its duties in that ideal activity, the overbalance of which, with the consequent indisposition to action, is his disease, he compels the reluctant good sense of the high yet healthful-minded Horatio to follow him in his wayward meditation amid the graves!

HAM. To what base uses we may return, Horatio! Why not may imagination trace the noble dust of Alexander till he find it stopping a bung-hole?

HOR. ’Twere to consider too curiously, to consider so.

HAM. No, faith, not a jot; but to follow him thither with modesty enough, and likelihood to lead it; as thus; Alexander died, Alexander was buried, Alexander returneth to dust; the dust is earth; of earth we make loam: And why of that loam whereto he was converted, might they not stop a beer-barrel?

Imperious Caesar, dead, and turnd to clay,

Might stop a hole to keep the wind away!

But let it not escape our recollection, that when the objects thus connected are proportionate to the connecting energy, relatively to the real, or at least to the desirable, sympathies of mankind; it is from the same character that we derive the genial method in the famous soliloquy, ‘To be, or not to be’ which, admired as it is, and has been, has yet received only the first-fruits of the admiration due to it.

We have seen that from the confluence of innumerable impressions in each moment of time the mere passive memory must needs tend to confusion; a rule, the seeming exceptions to which (the thunder-bursts in Lear, for instance) are really confirmations of its truth. For, in many instances, the predominance of some mighty Passion takes the place of the guiding Thought, and the result presents the method of Nature, rather than the habit of the Individual. For Thought, Imagination, (and I may add, Passion), are, in their very essence, the first connective, the latter co-adunative: and it has been shown, that if the excess lead to Method misapplied, and to connections of the moment, the absence, or marked deficiency, either precludes method altogether, both form and substance; or (as the following extract will exemplify) retains the outward form only.

My liege and Madam, to expostulate

What majesty should be, what duty is,

Why day is day, night night, and time is time,

Were nothing but to waste night, day and time.

Therefore—since brevity is the soul of wit,

And tediousness the limbs and outward flourishes,—

I will be brief. Your noble son is mad:

Mad call I it; for to define true madness,

What is’t, but to be nothing else but mad!

But let that go.

QUEEN. More matter with less art.

POL. MADAM, I swear, I use no art at all.

That he is mad, ’tis true: a foolish figure;

But farewell it, for I will use no art.

Mad let us grant him then: and now remains,

That we find out the cause of this effect,

Or rather say the cause of this defect:

For this effect defective comes by cause.

Thus it remains, and the remainder thus Perpend.

Does not the irresistible sense of the ludicrous in this flourish of the soul-surviving body of old Polonius’s intellect, not less than in the endless confirmations and most undeniable matters of fact of Tapster Pompey or ‘the hostess of the tavern’ prove to our feelings, even before the word is found which presents the truth to our understandings, that confusion and formality are but the opposite poles of the same null-point?

It is Shakespeare’s peculiar excellence, that throughout the whole of this splendid picture-gallery (the reader will excuse the confest inadequacy of this metaphor), we find individuality every where, mere portrait no where. In all his various characters, we still feel ourselves communing with the same nature, which is everywhere present as the vegetable sap in the branches, sprays, leaves, buds, blossoms, and fruits, their shapes, tastes, and odours. Speaking of the effect, that is, his works themselves, we may define the excellence of their method as consisting in that just proportion, that union and interpenetration, of the universal and the particular, which must ever pervade all works of decided genius and true science. For Method implies a progressive transition, and it is the meaning of the word in the original language. The Greek  is literally a way or path of transit. Thus we extol the Elements of Euclid, or Socrates’ discourse with the slave in the Menon of Plato, as methodical, a term which no one who holds himself bound to think or speak correctly, would apply to the alphabetical order or arrangement of a common dictionary. But as without continuous transition there can be no Method, so without a preconception there can be no transition with continuity. The term, Method, cannot therefore, otherwise than by abuse, be applied to a mere dead arrangement, containing in itself no principle of progression.

is literally a way or path of transit. Thus we extol the Elements of Euclid, or Socrates’ discourse with the slave in the Menon of Plato, as methodical, a term which no one who holds himself bound to think or speak correctly, would apply to the alphabetical order or arrangement of a common dictionary. But as without continuous transition there can be no Method, so without a preconception there can be no transition with continuity. The term, Method, cannot therefore, otherwise than by abuse, be applied to a mere dead arrangement, containing in itself no principle of progression.

Friend.

Hartley Coleridge writes in his life of Thomas, Lord Fairfax: It was a most ungentlemanlike act of the weekly-fast-ordaining Parliament or their agents to open Charles’s letters to his wife, and all historians who make use of them to blacken his character ought to forfeit the character of gentlemen.

Coleridge comments: How could a faithful historian avoid it? The Parliament had acted ab initio on their convictions of the King’s bad faith, and of the utter insincerity of his promises and professions; and surely the justification or condemnation of their acts must depend on, or be greatly modified by the question—were these convictions well grounded, and afterwards proved to be so by evidence, which could without danger to the state be advanced? What stronger presumption can we have of the certainty of the evidences which they had previously obtained, and by the year after year accumulation of which their suspicions had been converted into convictions, and justifying grounds of action? And was Henrietta an ordinary wife? Was Charles to her as Charles of Sweden to his spouse? The Swedes’ Queen was only the man’s wife, but Henrietta was notoriously Charles’s queen, or rather the He-queen’s She-king—a commander in the war, meddling with and influencing all his councils. I hold the Parliament fully justified in the publication of the letters; much more the historian. S.T.C.

MS.

Don Quixote is not a man out of his senses, but a man in whom the imagination and the pure reason are so powerful as to make him disregard the evidence of sense when it opposed their conclusions. Sancho is the common sense of the social mananimal, unenlightened and unsanctified by the reason. You see how he reverences his master at the very time he is cheating him.

Table Talk.

Rabelais is a most wonderful writer. Pantagruel is the Reason; Panurge the Understanding,—the pollarded man, the man with every faculty except the reason. I scarcely know an example more illustrative of the distinction between the two. Rabelais had no mode of speaking the truth in those days but in such a form as this; as it was, he was indebted to the King’s protection for his life. Some of the commentators talk about his book being all political; there are contemporary politics in it, of course, but the real scope is much higher and more philosophical. It is in vain to look about for a hidden meaning in all that he has written; you will observe that, after any particularly deep thrust, as the Papimania, for example, Rabelais, as if to break the blow, and to appear unconscious of what he has done, writes a chapter or two of pure buffoonery. He, every now and then, flashes you a glimpse of a real face from his magic lantern, and then buries the whole scene in mist. The morality of the work is of the most refined and exalted kind; as for the manners, to be sure, I cannot say much.

Swift was anima Rabelaisii habitans in sicco,—the soul of Rabelais dwelling in a dry place.

Yet Swift was rare. Can any thing beat his remark on King William’s motto,—Recepit, non rapuit,—‘that the Receiver was as bad as the Thief?’

Table Talk.

The Pilgrim’s Progress is composed in the lowest style of English, without slang or false grammar. If you were to polish it, you would at once destroy the reality of the vision. For works of imagination should be written in very plain language; the more purely imaginative they are the more necessary it is to be plain.

Table Talk.

In the story of Lady Melville of Colville and her three hours prayer—with the sufficient specimen of the ‘Gentilwoman in Culross’ Muse, I can find nothing but what is elevating and affecting in the former and in the latter a really striking specimen of smoothness with strength in the metre, and of propriety in the Thoughts, so much beyond the average as to surprize a reader unacquainted with the fact of the superior purity and sweetness of the Language used by Women of Rank in ages of Barbarism, whether from immaturity (as in England and Scotland) or from degeneracy, as in Constantinople under the later Greek Emperors, when the Ladies still used a Language which Xenophon and Menander would have acknowledged. Reducing the words to the present fashion of Spelling, and with the alteration of one monosyllable, the application of which in the Lines is now obsolete, I transcribe them, not disguising the wish, I feel, to see the whole Poem.

Tho’ Waters great do compass you about,

Tho’ Tyrants fret; tho’ Lions rage and roar;

Defy them all and fear not to win out—

Your Guide is near to help you evermore.

Tho’ point of Iron do pierce you wond’rous sore,

And Lusts more noisome seek your Soul to slay,

Yet cry on Christ, and he shall go before;

The nearer Heaven, the harder is the Way.

Rejoice in God! Let not your Courage fail,

Ye chosen Saints! that are afflicted here:

Tho’ Satan rage, he never shall prevail

Fight to the end, and stoutly persevere!

Your God is true: your Blood to him is dear:

Fear not the way since Christ is your Convoy:

When Clouds are past, the weather still grow[s] clear:

Ye sow in tears, but ye shall reap in Joy!

Common-place! Yes! So are the gales of Heaven, yet to the man who after long toiling up the rocky path has just reached the Brow of the Mountain, they are as delightful as tho’ they had been prepared by an especial Fiat at that moment.

MS.

Did not the Life of Arch[bishop] Williams [by the same divine] prove otherwise. I should have inferred from these Sermons that H[acket], from his first Boyhood had been used to make themes, epigrams, copies of verses, &c. on all the Sundays, Feasts and Festivals of the Church; had found abundant nourishment for this humour of Points, Quirks, and Quiddities in the study of the Fathers and Glossers; and remained an Under-Soph all his life long.

I scarcely know what to say. On the one hand, there is a triflingness, a Shewman or Relique-hawker’s Gossip, that stands in offensive Contrast with the momentous nature of the subject, and the dignity of the ministerial office, as if a Preacher, having chosen the Prophets for his theme should entertain his congregation by exhibiting a traditional Shaving Rag of Isaiah’s with the Prophet’s stubble hair on the dried up soapsuds. And yet on the other hand there is an innocency in it, a security of Faith, a fullness evinced in the play and plash of its overflowing that at other times give me the same sort of pleasure as the sight of Blackberry Bushes, and Children’s Handkerchief Gardens on the slopes of a rampart, the Promenade of some peaceful old town, that stood its last siege in the 30 Years War.

MS.

Crashaw seems in his poems to have given the first ebullience of his imagination, unshapen into form, or much of, what we now term, sweetness. In the poem, Hope, by way of question and answer, his superiority to Cowley is self-evident. In that on the name of Jesus equally so; but his lines on St. Theresa are the finest.

Where he does combine richness of thought and diction nothing can excel, as in the lines you so much admire—

‘Since ’tis not to be had at home,

She’l travel to a matyrdome.

No home for her confesses she,

But where she may a martyr be.

She’l to the Moores, and trade with them For this invalued diadem,

She offers them her dearest breath

With Christ’s name in’t, in change for death.

She’ll bargain with them, and will give

Them God, and teach them how to live

In Him, or if they this deny,

For Him she’ll teach them how to die.

So shall she leave amongst them sown,

The Lord’s blood, or, at least, her own.

Farewell then, all the world—adieu,

Teresa is no more for you:

Farewell all pleasures, sports and joys,

Never till now esteemed toys—

Farewell whatever dear’st may be,

Mother’s arms or father’s knee;

Farewell house, and farewell home,

She’s for the Moores and martyrdom.’

These verses were ever present to my mind whilst writing the second part of Christabel; if, indeed, by some subtle process of the mind they did not suggest the first thought of the whole poem.—Poetry, as regards small poets, may be said to be, in a certain sense, conventional in its accidents and in its illustrations; thus Crashaw uses an image:—

‘As sugar melts in tea away’;

which, although proper then, and true now, was in bad taste at that time equally with the present. In Shakespeare, in Chaucer there was nothing of this.

Allsop.

What a master of composition Fielding was! Upon my word, I think the Oedipus Tyrannus, the Alchemist, and Tom Jones the three most perfect plots ever planned. And how charming, how wholesome, Fielding always is! To take him up after Richardson, is like emerging from a sick room heated by stoves, into an open lawn, on a breezy day in May.

Table Talk

The difference between the composition of a history in modern and ancient times is very great; still there are certain principles upon which a history of a modern period may be written, neither sacrificing all truth and reality, like Gibbon, nor descending into mere biography and anecdote.

Gibbon’s style is detestable, but his style is not the worst thing about him. His history has proved an effectual bar to all real familiarity with the temper and habits of imperial Rome. Few persons read the original authorities, even those which are classical; and certainly no distinct knowledge of the actual state of the empire can be obtained from Gibbon’s rhetorical sketches. He takes notice of nothing but what may produce an effect; he skips on from eminence to eminence, without ever taking you through the valleys between: in fact, his work is little else but a disguised collection of all the splendid anecdotes which he could find in any book concerning any persons or nations from the Antonines to the capture of Constantinople. When I read a chapter in Gibbon, I seem to be looking through a luminous haze or fog:—figures come and go, I know not how or why, all larger than life, or distorted or discoloured; nothing is real, vivid, true; all is scenical, and, as it were, exhibited by candlelight. And then to call it a History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire! Was there ever a greater misnomer? I protest I do not remember a single philosophical attempt made throughout the work to fathom the ultimate causes of the decline or fall of that empire. How miserably deficient is the narrative of the important reign of Justinian! And that poor scepticism, which Gibbon mistook for Socratic philosophy, has led him to misstate and mistake the character and influence of Christianity in a way which even an avowed infidel or atheist would not and could not have done. Gibbon was a man of immense reading; but he had no philosophy; and he never fully understood the principle upon which the best of the old historians wrote. He attempted to imitate their artificial construction of the whole work—their dramatic ordonnance of the parts—without seeing that their histories were intended more as documents illustrative of the truths of political philosophy than as mere chronicles of events.

The true key to the declension of the Roman empire—which is not to be found in all Gibbon’s immense work—may be stated in two words:—the imperial character overlaying, and finally destroying, the national character. Rome under Trajan was an empire without a nation.

Table Talk.

The title is modest enough—Some Memorials—but they are a meagre Substitute for a Life of Mr. S. J.—a worthier Subject of Biography than Dr. S. Johnson—and this without denying the worth of the latter—but more thanks to Boswell than to the Dr’s own Works. S. T. C.

Among my countless intentional Works, one was—Biographical Memorials of Revolutionary Minds, in Philosophy, Religion, and Politics. Mr. Sam Johnson was to have been one. I meant to have begun with Wickcliff, and to have confined myself to Natives of Great Britain—but with one or two supplementary Volumes, for the Heroes of Germany (Luther and his Contemporaries) and of Italy (Vico).

MS.

Samuel Johnson, whom to distinguish him from the Doctor, we may call the Whig, was a very remarkable writer. He may be compared to his contemporary Defoe, whom he resembled in many points. He is another instance of King William’s discrimination, which was so much superior to that of any of his ministers. Johnson was one of the most formidable advocates for the Exclusion Bill, and he suffered by whipping and imprisonment under James accordingly. Like Asgill, he argues with great apparent candour and clearness till he has his opponent within reach, and then comes a blow as from a sledge-hammer. I do not know where I could put my hand upon a book containing so much sense and sound constitutional doctrine as this thin folio of Johnson’s Works; and what party in this country would read so severe a lecture in it as our modern Whigs!

A close reasoner and a good writer in general may be known by his pertinent use of connectives. Read that page of Johnson; you cannot alter one conjunction without spoiling the sense. It is a linked strain throughout. In your modern books, for the most part, the sentences in a page have the same connection with each other that marbles have in a bag; they touch without adhering.

Asgill evidently formed his style upon Johnson’s, but he only imitates one part of it. Asgill never rises to Johnson’s eloquence. The latter was a sort of Cobbett-Burke.

Table Talk.

Dr. Johnson’s fame now rests principally upon Boswell. It is impossible not to be amused with such a book. But his bowwow manner must have had a good deal to do with the effect produced;—for no one, I suppose, will set Johnson before Burke,—and Burke was a great and universal talker;—yet now we hear nothing of this except by some chance remarks in Boswell. The fact is, Burke, like all men of genius who love to talk at all, was very discursive and continuous; hence he is not reported; he seldom said the sharp short things that Johnson almost always did, which produce a more decided effect at the moment, and which are so much more easy to carry off. Besides, as to Burke’s testimony to Johnson’s powers, you must remember that Burke was a great courtier; and after all, Burke said and wrote more than once that he thought Johnson greater in talking than in writing, and greater in Boswell than in real life.

Table Talk.

Dr. Johnson seems to have been really more powerful in discoursing viva voce in conversation than with his pen in hand. It seems as if the excitement of company called something like reality and consecutiveness into his reasonings, which in his writings I cannot see. His antitheses are almost always verbal only; and sentence after sentence in the Rambler may be pointed out, to which you cannot attach any definite meaning whatever. In his political pamphlets there is more truth of expression than in his other works, for the same reason that his conversation is better than his writings in general.

Table Talk.

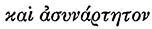

Timeless All Time.

Eolian Harp  Single Drum.1

Single Drum.1

Hence the E.H. pours forth delicious tones, and surges of Tone but which can be neither measured nor retained—the faintest of all memories, the memory, not of, but about a past sensation, broadly particularized by the wide general, delightful, sweet, tender, aerial &c. &c.——

Query. As Conversationists is not S. T. C.  Dr J. as Eol[ian] Harp to Single Drum. Hence the stores of remembered Sayings of the latter—while S. T. C. sparks

Dr J. as Eol[ian] Harp to Single Drum. Hence the stores of remembered Sayings of the latter—while S. T. C. sparks

Sparks that fall upon a River,

A moment bright, then lost for ever.

MS.

Pope like an old Lark who tho’ he leaves off soaring and singing in the heights, yet has his Spurs grow longer and sharper, the older he grows.

MS.

I think Crabbe and Southey are something alike; but Crabbe’s poems are founded on observation and real life—Southey’s on fancy and books. In facility they are equal, though Crabbe’s English is of course not upon a level with Southey’s, which is next door to faultless. But in Crabbe there is an absolute defect of the high imagination; he gives me little or no pleasure: yet, no doubt, he has much power of a certain kind, and it is good to cultivate, even at some pains, a catholic taste in literature. I read all sorts of books with some pleasure except modern sermons and treatises on political economy.

I have received a great deal of pleasure from some of the modern novels, especially Captain Marryat’s ‘Peter Simple’. That book is nearer Smollett than any I remember. And ‘Tom Cringle’s Log’ in Blackwood is also most excellent.

Table Talk.

Before I had ever seen any part of Goethe’s Faust, though, of course, when I was familiar enough with Marlowe’s, I conceived and drew up the plan of a work, a drama, which was to be, to my mind, what the Faust was to Goethe’s. My Faust was old Michael Scott; a much better and more likely original than Faust. He appeared in the midst of his college of devoted disciples, enthusiastic, ebullient, shedding around him bright surmises of discoveries fully perfected in after-times, and inculcating the study of nature and its secrets as the pathway to the acquisition of power. He did not love knowledge for itself—for its own exceeding great reward—but in order to be powerful. This poison-speck infected his mind from the beginning. The priests suspect him, circumvent him, accuse him; he is condemned, and thrown into solitary confinement: this constituted the prologus of the drama. A pause of four or five years takes place, at the end of which Michael escapes from prison, a soured, gloomy, miserable man. He will not, cannot study; of what avail had all his study been to him? His knowledge, great as it was, had failed to preserve him from the cruel fangs of the persecutors; he could not command the lightning or the storm to wreak their furies upon the heads of those whom he hated and condemned, and yet feared. Away with learning! away with study! to the winds with all pretences to knowledge! We know nothing; we are fools, wretches, mere beasts. Anon I began to tempt him. I made him dream, gave him wine, and passed the most exquisite of women before him, but out of his reach. Is there, then, no knowledge by which these pleasures can be commanded? That way lay witchcraft, and accordingly to witchcraft Michael turns with all his soul. He has many failures and some successes; he learns the chemistry of exciting drugs and exploding powders, and some of the properties of transmitted and reflected light: his appetites and his curiosity are both stimulated, and his old craving for power and mental domination over others revives. At last Michael tries to raise the Devil, and the Devil comes at his call. My Devil was to be, like Goethe’s, the universal humorist, who should make all things vain and nothing worth, by a perpetual collation of the great with the little in the presence of the infinite. I had many a trick for him to play, some better, I think, than any in the Faust. In the meantime, Michael is miserable; he has power, but no peace, and he every day more keenly feels the tyranny of hell surrounding him. In vain he seems to himself to assert the most absolute empire over the Devil, by imposing the most extravagant tasks; one thing is as easy as another to the Devil. ‘What next, Michael?’ is repeated every day with more imperious servility. Michael groans in spirit; his power is a curse: he commands women and wine; but the women seem fictitious and devilish, and the wine does not make him drunk. He now begins to hate the Devil, and tries to cheat him. He studies again and explores the darkest depths of sorcery for a receipt to cozen hell; but all in vain. Sometimes the Devil’s finger turns over the page for him, and points out an experiment, and Michael hears a whisper—‘Try that, Michael!’ The horror increases; and Michael feels that he is a slave and a condemned criminal. Lost to hope, he throws himself into every sensual excess,—in the mid career of which he sees Agatha, my Margaret, and immediately endeavours to seduce her. Agatha loves him; and the Devil facilitates their meetings; but she resists Michael’s attempts to ruin her, and implores him not to act so as to forfeit her esteem. Long struggles of passion ensue, in the result of which his affections are called forth against his appetites, and, love-born, the idea of a redemption of the lost will dawns upon his mind. This is instantaneously perceived by the Devil; and for the first time the humorist becomes severe and menacing. A fearful succession of conflicts between Michael and the Devil takes place, in which Agatha helps and suffers. In the end, after subjecting him to every imaginable horror and agony, I made him triumphant, and poured peace into his soul in the conviction of a salvation for sinners through God’s grace.

The intended theme of the Faust is the consequences of a misology, or hatred and depreciation of knowledge caused by an originally intense thirst for knowledge baffled. But a love of knowledge for itself, and for pure ends, would never produce such a misology, but only a love of it for base and unworthy purposes. There is neither causation nor progression in the Faust; he is a ready-made conjuror from the very beginning; the incredulus odi is felt from the first line. The sensuality and the thirst after knowledge are unconnected with each other. Mephistopheles and Margaret are excellent; but Faust himself is dull and meaningless. The scene in Auerbach’s cellars is one of the best, perhaps the very best; that on the Brocken is also fine; and all the songs are beautiful. But there is no whole in the poem; the scenes are mere magic-lantern pictures, and a large part of the work is to me very flat. The German is very pure and fine.

The young men in Germany and England who admire Lord Byron, prefer Goethe to Schiller; but you may depend upon it, Goethe does not, nor ever will, command the common mind of the people of Germany as Schiller does. Schiller had two legitimate phases in his intellectual character:—the first as author of the Robbers—a piece which must not be considered with reference to Shakespeare, but as a work of the mere material sublime, and in that line it is undoubtedly very powerful indeed. It is quite genuine, and deeply imbued with Schiller’s own soul. After this he outgrew the composition of such plays as the Robbers, and at once took his true and only rightful stand in the grand historical drama—the Wallenstein;—not the intense drama of passion,—he was not master of that—but the diffused drama of history, in which alone he had ample scope for his varied powers. The Wallenstein is the greatest of his works: it is not unlike Shakespeare’s historical plays—a species by itself. You may take up any scene, and it will please you by itself; just as you may in Don Quixote, which you read through once or twice only, but which you read in repeatedly. After this point it was, that Goethe and other writers injured by their theories the steadiness and originality of Schiller’s mind; and in every one of his works after the Wallenstein you may perceive the fluctuations of his taste and principles of composition. He got a notion of re-introducing the characterlessness of the Greek tragedy with a chorus, as in the Bride of Messina, and he was for infusing more lyric verse into it. Schiller sometimes affected to despise the Robbers and the other works of his first youth; whereas he ought to have spoken of them as of works not in a right line, but full of excellence in their way. In his ballads and lighter lyrics Goethe is most excellent. It is impossible to praise him too highly in this respect. I like the Wilhelm Meister the best of his prose works. But neither Schiller’s nor Goethe’s prose style approaches to Lessing’s, whose writings, for manner, are absolutely perfect.

Although Wordsworth and Goethe are not much alike to be sure, upon the whole; yet they both have this peculiarity of utter non-sympathy with the subjects of their poetry. They are always, both of them, spectators ab extra,—feeling for, but never with, their characters. Schiller is a thousand times more hearty than Goethe.

I was once pressed—many years ago—to translate the Faust; and I so far entertained the proposal as to read the work through with great attention, and to revive in my mind my own former plan of Michael Scott. But then I considered with myself whether the time taken up in executing the translation might not more worthily be devoted to the composition of a work which, even if parallel in some points to the Faust, should be truly original in motive and execution, and therefore more interesting and valuable than any version which I could make;—and, secondly, I debated with myself whether it became my moral character to render into English—and so far, certainly, lend my countenance to language—much of which I thought vulgar, licentious, and blasphemous. I need not tell you that I never put pen to paper as a translator of Faust.

I have read a good deal of Mr. Hayward’s version, and I think it done in a very manly style; but I do not admit the argument for prose translations. I would in general rather see verse attempted in so capable a language as ours. The French can’t help themselves, of course, with such a language as theirs.

Table Talk.

Tuesday Night, 13 Octr 1830.

Sir W. S., a faithful Cosmolater, is always half and half on the subject of the Supernatural in his Novels. The Ghost-seer and the Appearances are so stated as to be readily solved on the commonest and most obvious principles of Pathology; while the exact coincidence of the Events, and thus as in Guy Mannering, a complexity of Events with two perfectly coincident predictions so far exceeds our general experience, is so unsatisfactorily accounted for by the doctrine of Chances, as to be little less marvellous than the appearance itself would be, supposing it real. Thus by the latter he secures the full effect of Superstition for the Reader, while by the former he preserves the credit of unbelief and philosophic insight for the Writer—i.e. himself. I said falsely, the full effect: for that discrepance between the Narrator and the Narrative chills and deadens the Sympathy.

MS.

Mem.

In poetry, whether metrical or unbound, the super-natural will be impressive and obtain a mastery over the Imagination and feelings, will tend to infect the reader, and draw him to identify himself with, or substitute himself for, the Person of the Drama or Tale, in proportion as it is true to Nature—i.e. when the Poet of his free will and judgement does what the Believing Narrator of a Supernatural Incident, Apparition or Charm does from ignorance and weakness of mind,—i.e. mistake a Subjective product (A saw the Ghost of Z) for an objective fact—the Ghost of Z was there to be seen; or by the magnifying and modifying power of Fear and dreamy Sensations, and the additive and supplementary interpolations of the creative Memory and the inferences and comments of the prejudiced Judgement slipt consciously into and confounded with the Text of the actual experience, exaggerates an unusual Natural event or appearance into the Miraculous and supernatural.

The Poet must always be in perfect sympathy with the Subject of the Narrative, and tell his tale with ‘a most believing mind’; but the Tale will be then most impressive for all when it is so constructed and particularized with such [traits?] and circumstances, that the Psychologist and thinking Naturalist shall be furnished with the Means of explaining it as a possible fact, by distinguishing and assigning the Subjective portion to it’s true owner/—The Cobold of the Mine.…/—

MS.

The merit of a novellist is in proportion (not simply to the effect but) to the pleasurable effect which he produces. Situations of torment, and images of naked horror, are easily conceived; and a writer in whose works they abound, deserves our gratitude almost equally with him who should drag us by way of sport through a military hospital, or force us to sit at the dissecting table of a natural philosopher. To trace the nice boundaries, beyond which terror and sympathy are deserted by the pleasurable emotions, to reach those limits, yet never to pass them, hie labor, hie opus est. Figures that shock the imagination, and narratives that mangle the feelings, rarely discover genius, and always betray a low and vulgar taste.… The romance writer possesses an unlimited power over situations; but he must scrupulously make his characters act in congruity with them. Let him work physical wonders only, and we will content to dream with him for a while; but the first moral miracle which he attempts he disgusts and awakens us.… The extent of the powers that may exist, we can never ascertain; and therefore we feel no great difficulty in yielding a temporary belief to any, the strangest of things. But that situation once conceived, how beings like ourselves would feel and act in it, our own feelings sufficiently instruct us: and we instantly reject the clumsy fiction that does not harmonise with them.

Review of Lewis’s The Monk in the

Critical Review for February 1797.

Would to heaven I were with you! [Allsop] In a few days you should see that the spirit of the mountaineer is not yet utterly extinct in me. Wordsworth has remarked (in the Brothers, I believe),

The thought of death sits light upon the man

That has been bred, and dies among the mountains.