The future is very dark in Europe, and to me it looks as if we were entering upon a period quite new in history. … Whether our period of economical enterprise, unlimited competition, and unrestrained individualism, is the highest stage of human progress is to me very doubtful; and sometimes when I see the existing conditions of European (to say nothing of American) social order, bad as they are for the mass alike of upper and lower classes, I wonder whether our civilization can maintain itself against the forces which are banding together for the destruction of many of the institutions in which it is embodied, or whether we are not to have another period of decline, fall, and ruin and revival, like that of the first thirteen hundred years of our era. It would not grieve me much to know that this were to be the case. No man who knows what society at the present day really is, but must agree that it is not worth preserving on its present basis.1

These were strong words—but they were not about the Europe of 1914. Disillusionment, disgust and the anticipation of disaster lend a sharply modern tone, but this was Charles Eliot Norton (1827–1908), editor, art critic, and educator, writing home to America in 1869 as he toured Britain, Italy, Germany, and France. Over sixty years later, as Europe yet again spiraled into unrest, T. S. Eliot would quote this passage in his lectures in honor of Norton at Harvard University in 1932. To Eliot, Norton stood for the viewpoint that culture was the mainstay of a decent society. Without it, everything came to ruin. As Eliot put it, “the people which ceases to care for its literary inheritance becomes barbaric; the people which ceases to produce literature ceases to move in thought and sensibility.”2

Henry James wrote to Edith Wharton in August 1914 that he felt “all but unbearably overdarkened by this crash of our civilization.”3 But this was a crash that had been a long time coming, and which would not prove to be final. Norton and Eliot’s comments, straddling several decades either side of the First World War, demonstrate that a sense of impending disaster for humanity, and the hope that culture might avert it, were longstanding concerns. In his Harvard lectures of 1932–33, Eliot carefully distanced both himself and Norton from Matthew Arnold’s mid-Victorian view of culture as a force for the propagation of good morals.4 Although he shared Arnold’s concern for “literary inheritance,” Eliot would place the value of literature not in what it taught but what it showed. Culture was not the cause but the product of a balanced society, one rich in “thought and sensibility.” Good writing was not a conduit for truths passed on from the old to the young, but an indicator of a healthy, individual curiosity about self and context. “We must write our poetry as we can,” Eliot concluded, “and take it as we find it”—a sentiment very much in line with Ralph Waldo Emerson’s delight in “Man Thinking” instead of parroting the traditions of the past.5

This habit of mental self-reliance, so prevalent in American literature from Emerson onward, was, and perhaps still is, counterbalanced by the potential consequences of its failure, the specter of the “barbaric” so vivid to Eliot in the 1930s.6 From the mid-nineteenth century, ideas of evolutionary progress derived from the work of Charles Darwin and Herbert Spencer were projected into the swiftly changing scenery of Gilded Age America by social theorists such as William Graham Sumner and Adna Weber, for whom urban life was an endless and vicious round of competition for space, work, food, and time. Darwin and Spencer had promised improvement toward perfection, but Weber’s generation projected bleaker outcomes. Failure in this daily battle for resources could lead to personal extinction in the greater cause of social refinement, or could result in the kind of degeneration forecast by Ray Lankester, and dramatized in the naturalistic fiction of Émile Zola and Theodore Dreiser, or in the dystopian romances of H. G. Wells.7 Success in the struggle, as Thorstein Veblen argued, led merely to interclass conflict and, through “conspicuous consumption” and “conspicuous waste,” to the atrophy of the leisure class—whose very existence was both the defining element of a “civilized” society and its most potent internal threat.8 Although these ideas did not all originate in America, they resonated strongly in the imagination of many early twentieth-century citizens, who inherited, or self-consciously adopted, a powerful but confused legacy from the nation’s Puritan past, in which the value of the individual, the power of the written word, a strong work ethic, the taint of materialism, the certainty of retributive judgment on society, and the hope of some ideal world beyond were haphazardly jumbled together. Even for those who rejected the religious framework which supported (and rationalized) such concepts, stubborn patterns of thought remained. The anticipation of destruction was perhaps the most enduring. James called it “the imagination of disaster.”9

So, the idea of “a war that will end war” was nothing new in 1914.10 Rumors of secret pacts and alliances between European nations from the beginning of the century had raised public expectations of conflict, which had been narrowly avoided in a series of diplomatic crises from 1908 onward.11 When war came, it shocked the world, but simultaneously fulfilled an expectation of an epic conflict between the great nations of the world, which would ultimately purge and strengthen the civilized and virtuous races of humankind. Wharton wrote to the American scholar Gaillard Lapsley in December 1914, “The only consoling thought is that the beastly horror had to be gone through, for some mysterious cosmic reason of ripening and rotting, and the heads on whom that rotten German civilisation are falling are bound to get cracked.”12 For others, the progress brought by war was not so much a bitter consolation as a positive objective. Cleveland Moffett would write in 1916 that the American union “born of war” proved that conflict was essential for peace: “And why not ultimately the United States of Europe, the United States of Asia, the United States of Africa, all created by useful and progressive wars? … ‘United we stand, divided we fall,’ applies not merely to states, counties and townships, but to nations, to empires, to continents. Continents will be the last to join hands across the seas (having first waged vast inter-continental wars) and then, after the rise and fall of so many sovereignties, there will be established on earth the last great government, the United States of the World!”13 From the sinking of the Pequod in Moby Dick (1851) to the freezing over of New York in The Day after Tomorrow (2004), the secular apocalyptic narrative is a powerful, recurring presence in American popular culture. Eliot’s poem The Waste Land (1922) both drew on and helped to define the genre. To Henry James, schooled in his father’s Swedenborgian conceptions of heaven and hell; to Edith Wharton, well-versed in the social theories of the early twentieth century; and to Grace Fallow Norton, raised in the evangelical fervor of small-town Minnesota, the apocalyptic habit of language and thought was a hard one to break.14 Each of these writers in their own way carried a deep sense of the precariousness of human civilization. When the war began, it seemed to them, as to many others, that something decisive was finally at hand. Whether judgment and destruction would be meted out by a vengeful deity or an indifferent nature, whether the end would be swift or slow, everyone had a theory and a secret fear.

Henry James, Grace Fallow Norton, and Edith Wharton were among many American exiles for whom London and Paris were irresistible points of cultural attraction and production, centers of the very “civilization” which appeared to be threatened by the political and military maneuvers of the European nation-states. As John Dos Passos would note decades later, American international perspectives in the early twentieth century were characterized by “a nostalgic geography of civilized and cultured Europe where existence was conducted on a higher plane than the grubby materialism of American business.” In the popular imagination, this was especially true of Paris, which seemed to many “the crossroads of civilization.”15 James, who had lived in Europe, mostly in England, for some forty years, was more shrewd than most people about the failings of European society. However, as the following pages show, the coming of war, and the threat which it offered to a social world which he had observed, admired, and mimicked for decades, forced a searching reappraisal of the value of that world, and raised sharp questions about how the writer should respond to conflict and distress: with actions or with words? Wharton, however, based permanently in Paris since the break up of her marriage in 1910, had quickly made herself at home in the elegant and exclusive circles of the Faubourg St. Germain, where the good conversation and sophisticated taste which she prized were recognized and maintained. As her friend Percy Lubbock noted in later years, “She had attained, and not without complacency she knew it, to a far closer intimacy with France than is often granted to an alien—with France of the French, the old and the traditional, which has never easily opened to a stranger’s knock.”16 However, in 1914, this process of assimilation was in its early stages, and Wharton’s passion for the integrity of France during the war had all the idealism and raw enthusiasm of the newcomer. At this stage, her attitude was not unlike that of the fictional American exiles in her postwar novel A Son at the Front (1923) who felt that, “If France went, western civilization went with her.”17 But, there was self-irony in this retrospective statement, and Wharton’s idealism would be tested and overhauled during the next four years. Nevertheless, in the political and ideological tussle for American popular sympathy during the early years of the war, the trope of France as a symbol of civilization was a recurrent one. Both Wharton and James would exploit it for practical, if charitable, purposes. Grace Fallow Norton, too, would subscribe to the apocalyptic vision of the war as a threat to social, political, even to geological, stability. However, her conception of civilization was more concerned with the rights of the common citizen than with the preservation of an elitist culture—even while she participated in that culture. France, to Norton, represented the possibility of personal freedom, both in terms of democratic governance and moral tolerance. If her concerns were less commonly voiced among the literary classes of the day, they were perhaps more representative of the attitudes of less privileged, and also younger, Americans. Norton’s views at the outbreak of the war certainly suggest that the later, more pronounced social perspectives of writers such as Cummings and Dos Passos were not kneejerk reactions to their experience of war, but rather extensions of deep-seated changes already in process in the fabric of American society. However, in August 1914, the most urgent question for each of these writers was how to define the boundary between the demands of artistic response with those of real life. Put more simply, if civilization was falling apart, what on earth were they supposed to do next?

It began for Henry James as a nightmare from which there was “no waking save by sleep.”18 On 5 August, through the balmy summer weather, news of Britain’s declaration of war in response to Germany’s invasion of Belgium reached James’s home in the little town of Rye, near the coast of Sussex on the English Channel. The change in James’s mood was immediate and electrifying—captured with photographic clarity in a letter to his friend Howard Sturgis. The first half, written the previous day, before papers arrived in Rye bearing the dramatic news, is relaxed and expansive, full of chatter about friends; the second half, written in full knowledge of events, is a darker, yet strangely energized text, passionate in its dismay and its condemnation of the German and Austrian rulers: “The taper went out last night, and I am afraid I now kindle it again to a very feeble ray—for it’s vain to talk as if one weren’t living in a nightmare of the deepest dye. … The plunge of civilization into this abyss of blood and darkness by the wanton feat of those two infamous autocrats is a thing that so gives away the whole long age during which we have supposed the world to be, with whatever abatement, gradually bettering, that to have to take it all now for what the treacherous years were all the while really making for and meaning is too tragic for any words.”19 Nevertheless, words were what James turned to, over the following days, as a means of ordering his intense reactions. Always richly articulate and self-conscious, his letters now took on an unfamiliar sense of urgency and scope. Treachery, nightmare, murder, abyss: these words flowed again and again from James’s pen as his powerful imagination struggled to accommodate the scale and the horror of the conflict. It was, he recognized at once, about much more than the immediate political objectives of the warring nations. James appeared to grasp instantly what many social commentators would take years to work out. The lasting impact of the approaching storm would be social and cultural, and the world he knew would not survive it. It was not just the fact that the old order was passing that grieved him; it was the suspicion that it had all been, as he wrote to Rhoda Broughton, a sham: “Black and hideous to me is the tragedy that gathers, and I’m sick beyond cure to have lived on to see it. You and I, the ornaments of our generation, should have been spared this wreck of our belief that through the long years we had seen civilization grow and the worst become impossible. The tide that bore us along was then all the while moving to this as its grand Niagara—yet what a blessing we didn’t know it.”20

In 1914, James was seventy-one years old. His health was not robust; he suffered from angina and bouts of nausea and depression. He was a foreign citizen of a neutral nation, and he had never involved himself much in public affairs. He was, as he admitted to Broughton, one of the “ornaments” of his generation. It must have seemed unlikely to anyone, even to himself, that he would take an active role in this crisis. Nevertheless, as the early days of the conflict stretched anxiously to weeks, and then to months, James found himself drawn into the war effort. Initially, he attempted to continue working on his two current writing projects: the contemporary American novel The Ivory Tower, and the third volume of his autobiography The Middle Years. But the depressing news from the front and the tension in the air made it difficult to concentrate. It did not seem possible to write about a world that was falling apart so violently.21 He wrote to his nephew William James Junior: “The extraordinary thing is the way that every interest and every connection that seemed still to exist up to exactly a month ago has been as annihilated as if it had never lifted a head in the world at all.”22 But, this was only how it seemed. In reality, James was being propelled by his past into the storm of the present moment.

“Civilization” was one of James’s recurring watchwords in his early letters about the war, but his own parameters for the meaning of the word are not easy to define. Henry F. May characterizes the American ideal of civilization before 1912 as a fragile, golden “triptych” of moralism, progress, and culture—a culture still heavily reliant on the British Victorian voices of Thomas Carlyle, John Ruskin, and Matthew Arnold.23 James had to an extent distanced himself from this triptych by his decision to settle among the complex social systems of Europe, and there to refine his sharp sense of the subjectivity of all human judgment—although he was hardly going to escape the legacy of Carlyle, Ruskin, and Arnold by moving to England. However, like Charles Eliot Norton, who traveled with the young James in Europe, published his early work in the North American Review, and introduced him to Ruskin in person in 1869, James was ready to form his own opinions about European civilization and its relationship to culture, especially to literary production. For James, “civilization” denoted something rich and precious and old—but it was not always, for him, a concept above censure. In his biography of Hawthorne (1879), James noted the lack of “items of high civilization” in American life in the 1840s: “No sovereign, no court, no personal loyalty, no aristocracy, no church, no clergy, no army, no diplomatic service, no country gentlemen, no palaces, no castles, nor manors, nor old country-houses, nor parsonages, nor thatched cottages nor ivied ruins; no cathedrals, nor abbeys, nor little Norman churches; no great Universities nor public schools—no Oxford, nor Eton, nor Harrow; no literature, no novels, no museums, no pictures, no political society, no sporting class—no Epsom nor Ascot!”24 It is a notorious list, but many of James’s readers forget that he had his tongue firmly in his cheek when he made it. James’s point was that Hawthorne did not need these things to write. No American author did: “The American knows that a good deal remains—that is his secret, his joke, as one might say.”25 It was a joke at Arnold’s expense. For Arnold, “civilization” consisted of the physical infrastructure of a highly developed society: institutions, architecture, and amenities.26 James admired Hawthorne’s rejection of European institutions and tropes, and celebrated his ability to observe, to think for himself, and to draw his own conclusions about American society. Elsewhere, the young James took an even sharper view of “civilization,” which seemed at times to signify little more than the fripperies and frivolities of Parisian life that he lampooned in his essays for the New York Tribune in 1875–76. Here, French civilization was characterized by consumption and display—extravagant clothes, light opera, and candy boxes. “The bonbonnière, in its elaborate and impertinent uselessness,” he wrote, “is certainly the consummate flower of material luxury; it seems to bloom, with its petals of satin and its pistils of gold, upon the very apex of the tree of civilization.”27

Forty years later, James had apparently changed his mind. Civilization seemed to him now to denote not just the trappings of a fair and cultured society, but also the abstract principles on which such a society was built. In his essay “France,” published in The Book of France, a fundraising venture edited by Winifred Stephens to raise money to support war refugees, he would write ardently that “the idea of what France and the French mean to the educated spirit of man” would be the most “general ground in the world, on which an appeal might be made, in a civilised circle.”28 He was no longer thinking about chocolate wrappers, or even social niceties. Civilisation now encompassed the complex social, personal, and artistic relationships within a community or a nation, the “good deal that remains” when artefacts and systems break down—or as he phrased it in 1915 “the life of the mind and the life of the senses alike.” Like so many of his countrymen, indeed like his own fictional characters, James had grown to see France as the place where these elements could be “taken together in the most irrepressible freedom of either.”29 Now it was under shell fire. After the initial disbelief and dismay, James reacted with fury, especially after the bombardment of Rheims Cathedral, which seemed to him “the most hideous crime ever perpetrated against the mind of man,” a turn of phrase which emphasized how he perceived even the brutally physical effects of the war, in its early days, in intellectual and historical terms. “There it was,” he wrote to Wharton, “and now all the tears of rage of all of the bereft millions and all the crowding curses of all the wondering ages will never bring a stone of it back!”30 Unknown to James, Wharton’s friend Alfred de Saint-André translated a long section of this passionate letter and read it to a session of the Académie Française on 9 October. It was also published in the Journal des Débats the following day. On receiving the news, James declared himself “honoured by such grand courtesy,” but this incident must also have alerted him to the possibility that he could have a public role in the crisis.31 This was, one suspects, an unfamiliar idea to this media-shy writer, who had found the reading public increasingly elusive over the past twenty years—unfamiliar, but not unwelcome.

In contrast, Wharton lost no time in stepping into the limelight. In July 1914, she had taken a three-week motoring trip to Spain with her intimate friend Walter Berry, the president of the American Chamber of Commerce. They had driven back to Paris, now thick with rumors and apprehension, at the month’s close. Her original plan had been to leave at once for England, where she had taken a two-month lease on Stocks in Buckinghamshire, the country mansion owned by her fellow novelist Mary Ward. But Wharton found herself caught up in the chaos of national mobilization on 1 August, which rushed away men of fighting age to the front but also immobilized the civilian population. It was not just that it was impossible to travel, all trains having been commandeered for military purposes; there was also a sense of emotional heaviness and helplessness that fell on the city with the momentous events of the war. It seemed to her like a “monstrous landslide” which had “fallen across the path of an orderly laborious nation, disrupting its routine, annihilating its industries, rending families apart, and burying under a heap of senseless ruin the patiently and painfully wrought machinery of civilization.”32 Civilization—it was the word of the moment, but no one seemed to be able to agree exactly what it meant. For Wharton, who used the term more generously than James, it encompassed the architecture and government of a nation, its history, its tradition, its artistic culture, its cuisine, its daily, domestic way of life. Having just selected France as her permanent home, these things currently seemed to Wharton to be infinitely more superior there than anywhere else in America or Europe. France and civilization seemed indivisible, and Wharton was ready to defend both.

Within a fortnight of the mobilization, she had joined the executive committee of the American Ambulance, and had opened an ouvroir for twenty seamstresses, laid off from the couture houses, which had closed as soon as war was announced. This workroom, supported by donations from Wharton’s wealthy friends, would quickly grow to accommodate ninety women, including refugees from Belgium and northern France, and would lead Wharton into a further series of charitable projects over the months and years ahead. As though to symbolize the two directions in which Wharton’s life was being pulled, the workshop produced French army uniforms to be worn at the front, alongside fine lingerie and couture dresses to be worn in the glamorous townhouses of Washington and New York. However, no sooner had she set this project going than Wharton was on the move again. Through Berry’s influence, she managed to secure a passage across the English Channel to Folkstone on 27 August, where James met her and took her back to Lamb House for the evening to hear the news from Paris, before she joined her servants at Stocks for her holiday as planned. Berry even pulled strings to allow Wharton’s car to be shipped to England, a remarkable feat at a moment when most vehicles and their drivers were being requisitioned by the army. But Wharton couldn’t relax. Restless and anxious for news, after only two weeks in the lush English countryside, she negotiated with the Wards for them to return to Stocks, while she moved up to stay at their London house in Grosvenor Square. In mid-September, James came up from Rye to visit her for four days, and found himself confronted with both the feverish atmosphere of the capital city and Wharton’s growing resolve to return to Paris—which she did a week later. James watched her go with a mix of admiration and concern. Her impulse was, he told her, “a very gallant and magnificent and ideal one,” but he also implored her, “for pity’s sake—if there be any pity in the universe now!—‘take care of yourself.’”33

When Wharton arrived back in Paris at the end of September, she found that she had missed momentous events, and that she had a tricky situation to resolve. While she had been away, the German army had advanced with breathtaking speed to within thirty miles of Paris, only to be halted by a combined French and British force at the First Battle of the Marne, a costly engagement on both sides in which nearly half a million men died. As the two great armies tried to outmaneuver each other along the line of the River Marne, the precarious balance of strength was tipped toward the Allies by General Maunoury’s inventive move of rushing six thousand extra troops to the front in Parisian motor taxi cabs, thus creating what was later hailed as “the first internal combustion-engined army in history.”34 After a week of vicious fighting, the Germans were driven back to the River Aisne, and the long stalemate of the next four years began to take shape. During the crisis, thousands of civilians had been evacuated south of Paris, including the “philanthropic lady” in whose house Wharton had established her workroom, and the manageress of the venture, who carried away all the operating funds, worth nearly two thousand dollars.35 The Red Cross intervened and the money was returned, but Wharton had to find the workshop a new home, which was eventually secured in a building owned by the Petit St. Thomas, a few blocks from her home at 53 Rue de Varenne, to assemble a new team of volunteers and to restore the confidence of her workers. She was not sure where to start, but two women who had heard about her difficulties came to her aid, and would prove invaluable over the coming months: Renée Landormy, who assumed responsibility for the workshop, and Elisina Tyler, the Italian wife of Royall Tyler, an American art critic living in Paris. Elisina Tyler would become Wharton’s right-hand woman in all of her charitable projects. Tyler, formerly the Countess Palamidessi di Castelvecchio, was energetic and charming, a woman of “inexhaustible resourcefulness”; she was not intimidated by committees, and knew how to soothe the impetuous and occasionally high-handed Wharton.36 Undoubtedly, Wharton’s wartime activities were an astonishing achievement, but she could not have done half of what she did without Tyler’s organizational flair and diplomacy.

In the autumn of 1914, Wharton formed a committee of her American, French and Belgian contacts to establish a new charity, the American Hostels for Refugees. This organization worked in collaboration with the Foyer Franco-Belge, which was founded in the opening weeks of the war by a group of French intellectuals including the writer André Gide and the critic Charles du Bos, but which was now overwhelmed by the numbers of refugees pouring into the capital after the fierce fighting around Ypres, which decimated the civilian population and left over ten thousand people homeless.37 The American Hostels for Refugees was in many ways a glamorous enterprise; it was based in a large, handsome building in the Champs Elysées owned by the Comtesse de Béhague, and financially supported by a glittering list of American literati and socialites, including Henry James, Wharton’s publisher Charles Scribner, her sister-in-law Mary Cadwaladar Jones, the new American ambassador to Paris William Graves Sharp, and other recognizable names from the East Coast upper classes: Adamses, Roosevelts, Chanlers, and Nortons. Hermione Lee finds it ironic that the social world which Wharton had abandoned, and which she satirized so ruthlessly in her fiction, was the main source of support for her aid work—so much so that the list of contributors to her charities “reads like the New York Social Register.”38 All the same, it worked. As Wharton’s biographer Shari Benstock notes, her fund-raising activities were “on a scale that in our time only corporations could undertake.”39 Her organization was committed to providing the basics of shelter and cheap food for the displaced arriving in Paris, until they could find jobs and homes of their own. The demand was daunting; in the first month alone, the two organizations working together lodged and clothed 878 refugees, found work for 153 of these, and served 16,287 free meals.40 But the numbers would only increase, and by the end of the war, the accueil (reception), as Wharton called it, was caring for five thousand refugees at a time. Wharton wrote appeal after appeal in the American press, shamelessly exploiting the most emotive stories she could find. As she wrote to Elisina Tyler: “I always get money by the ‘tremolo’ note, so I try to dwell on it as much as possible.”41 The committee soon realized that to operate effectively, they required support services such as cheap restaurants, coal supplies, a pharmacy, a nursery, and a hospital. Most of the new arrivals were hungry, exhausted, and ill. The small medical unit of thirty beds, for which Wharton launched an appeal in January 1915, would grow into a network of health services, a section of which developed as the Tuberculeux de la Guerre, a group of four large hospitals for civilian and military victims of tuberculosis. One of these, La Tuyolle, was taken over by the French government at the end of the war, and was still running when Wharton wrote her autobiography almost twenty years later.42

Just as this project was taking shape, in November 1914, Walter Berry left Paris to travel as a neutral observer to Germany and Belgium. His Chamber of Commerce position as the representative of a nation which both the Allies and the Central Powers were hoping to win over allowed him to move freely across Europe as few others could in those months. Wharton complained on his return that “his imagination seems less sensitive than it used to be” and that he had little to tell her in the way of “illuminating incident.”43 She did not consider that he may have been reluctant to describe to her in vivid detail all that he had seen. But even the “solid facts” that he did pass on gave Wharton a fascinating and disturbing glimpse of the world behind the front. The German army was in good order, prisoners’ camps were “fairly decent,” and the German people seemed to believe they were fighting to defend themselves. There was no chance of an early end to hostilities. Belgium on the other hand had been ripped apart, orphaned children roamed in devastated villages, and the great medieval library at Louvain had been burned to the ground—although Berry suspected the Germans of having carried off its treasures to Berlin before they set it alight. Wharton’s curiosity was fired, as was her sense that her own literary abilities would do more justice to the scene than Berry’s stolid account.

As 1915 approached, Wharton began to organize a series of fashionable concerts to raise money for out-of-work musicians, another category of Parisian worker with little means of making money in the general austerity of war. But she soon tired of making arrangements for refreshments, and ordering up programs: “I vaguely thought one had only to ‘throw open one’s doors’ as aristocratic hostesses do in fiction,” she wrote to her friend Mary Berenson in Italy. “Oh my! I’d rather write a three volume novel than do it again.”44 It was a telling remark; Wharton would much rather have been writing than organizing. Her comment also suggests that her models for activity were as much drawn from the world of fiction as from reality. She was not alone in this; many others, including those fighting at the front, had equally little idea of how to approach the new challenges facing them. There was also in Wharton’s deeply aristocratic mind a distaste for the crush and the crowd of such events and for throwing open one’s doors. She passed on the project to her friend Alice Garrett after half a dozen events. Nevertheless, she would find a use for these experiences later, when she came to write her fiction about Paris during the war.

Wharton, however, was not the only American who felt the need to support the Allied war effort. Upper-class American exiles swiftly endorsed and supported it, but also at times exploited it. Indeed, some of Wharton’s sharpest vitriol in her letters and fiction is reserved for the high-society volunteers who appeared to be enjoying themselves more than they were making any discernible contribution, for the large hotels which set aside some rooms as “hospitals” to be able to fly the Red Cross flag and thereby avoid shelling but without taking in patients, and for those bankers, businessmen, and their wives who seemed to regard the war as another curiosity of Europe. This charge could hardly be levied at Richard Norton, son of Charles Eliot Norton and former director of the American School of Classical Studies in Rome. Norton had been holidaying in England when war broke out, but traveled at once to Paris to see how he could help. At the American Hospital, hastily established at Neuilly in a new stone building intended as a boys’ school, Norton was struck by the number of needless deaths caused by the hopelessly slow process of getting the wounded to the operating table—a combination of hand stretcher, horse-drawn cart and railway train, which often took days. He also heard that American motorists trying to drive to the front to catch a glimpse of the fighting were getting in the way.45 He set to work to reverse this irony. A few days after leaving, he was back in London working with the British Red Cross to set up an independent ambulance unit, which would swiftly take shape as the American Volunteer Motor-Ambulance Corps. Later in the war, this would merge with the Morgan-Harjes unit to form a group that became known as the Norton-Harjes Section.46 This unit remained distinct from the larger American Field Ambulance Service organized by A. Piatt Andrew, until both were disbanded and subsumed into the U.S. Army Ambulance Service in August 1917. Richard Norton, refined, highly educated, and sporting a monocle, was an unlikely but charismatic leader. As the war unfolded, he organized scores of young volunteers, mostly Ivy League students and graduates, to serve at the front, many of whom paid their own expenses and brought their own valuable automobiles. Dos Passos, who joined the corps in 1917, described Richard Norton as an “aesthete, indomitable archaeologist, the man who smuggled half the Ludovici throne out of Italy, a Harvard man of the old nineteenth-century school, snob if you like, but solid granite underneath.”47 Well connected in the upper reaches of American society both in Europe and at home, he lost no time in mobilizing his contacts as donors and fund-raisers, including James, who within a few weeks had offered to act as a public spokesman for the corps. It was an unusual gesture for this deeply private, at times reclusive, writer, and it heralded a profound shift in James’s view of the role of the artist. From this point on, James’s reactions to the events on the Continent would be public as well as private. They would be political as well as artistic. James had abandoned the ivory tower in more ways than one.

On clear days, from his home, Lamb House in Rye, James could hear the rumble of artillery across the Channel, barely thirty miles away. But the war came even closer to home, sometimes in very tangible and personal ways. The day after Wharton sailed for France, the first group of Belgian refugees arrived in the town. James had promised them the use of the “studio” at Lamb House, a former chapel in the garden, as a day center. They came late in the evening, and as James stood at his doorstep to see the new arrivals come up the lane, he received an “unforgettable impression.” Over the old “grass-grown cobbles, where vehicles rarely pass,” came the little procession, eager and quiet, except for the weeping of one young woman carrying a small child. “The resonance through our immemorial old street of her sobbing and sobbing cry,” James wrote, “was the voice itself of history.”48 Refugees arrived and young friends left. Desmond McCarthy joined the Red Cross. Hugh Walpole, rejected from the army because of poor eyesight, went to Russia as a correspondent for the Daily Mail. Rupert Brooke and Wilfred Sheridan signed up for military service. This was not always an expression of patriotic fervor, but for some was simply an acceptance of a fate that seemed universal and inevitable. As Brooke expressed it: “Well, if Armageddon’s on, I suppose one should be there.”49 In early September, James’s “invaluable and irreplaceable” valet Burgess Noakes, who had worked for him since 1901, enlisted and left for training. It was, as James complained to Wharton, “like the loss of an arm or a leg.”50

James’s emotional reactions to the first few weeks of the war were characterized by the contrasting economies of scale and time in which he attempted to locate them. On the one hand, the tragedy was of biblical proportions, the failure of the civilized world, the climax of history; it was also a deeply personal wound, a keenly felt and permanent loss. James’s desire to identify with the pain and dismemberment of war is striking for many reasons—not least because of its similarity to his feelings about the American Civil War and the mysterious injury which prevented him from serving in the Northern Army. His two younger brothers Wilky and Robertson had enlisted, as did two of James’s cousins, Gus Barker and Will Temple. Both cousins were killed in action, leaving James with a complex emotional legacy of regret and relief. In the second volume of his autobiography, Notes of a Son and Brother, published only a few months before the First World War began, James describes—with a tantalizing lack of detail—how while helping to work a fire pump at a blaze in a Newport stable in 1861 he had done himself “in face of a shabby conflagration, a horrid if an obscure hurt.”51 The nature of this injury has been hotly debated. Many scholars have interpreted it as some form of physical or psychological castration—through it may simply have been a back strain.52 Whatever had actually happened to him, it seemed to James symbolic of the violence on the national battlefield: “One had the sense, I mean, of a huge comprehensive ache, and there were hours at which one could scarce have told whether it came most from one’s own poor organism, still so young and so meant for better things, but which had suffered particular wrong, or from the enclosing social body, a body rent with a thousand wounds and that thus treated one to the honour of a sort of tragic fellowship.”53

This incident and the language in which James describes it have been so heavily analyzed that it has become a critical commonplace to point out the sexual potency of the imagery; the fantasy of inclusion in the masculine community of military service; the artistic withdrawal to an observing rather than a participating role; and the eerie, generational repetition of the childhood accident in which his father, Henry James Senior, lost a leg after a fire in another stable.54 When James said that Noakes’s absence was “like the loss of an arm or a leg,” he used an image charged with a deep, familial echo—an image that must have seemed doubly resonant when Noakes returned from the front the following spring, with his hearing impaired and a permanent limp from a shrapnel wound. Adeline Tintner interprets James’s willingness to publish “propaganda” in order to “publicize the British war effort,” as a belated reaction to the repressed guilt he experienced for his nonparticipation in the Civil War, a guilt which he had finally overcome by relating the event to his readers in Notes of a Son and Brother.55 However, there are other ways of interpreting James’s own personal discomfort.

James’s sense of the interplay between the individual and the nation governs his response to war both in 1861 and in 1914. Physical pain is always a lonely experience—a fact thrown into sharp relief by the inability of scholars to fathom the nature of James’s own isolating injury. Nevertheless, his image of the nation as a wounded body highlights his sense that in wartime the normal boundaries between self and society are realigned, and the pain of the individual, whether soldier or civilian, takes on a broader political significance than at other times, as do other kinds of sensation and action (or inaction). In James’s description of his “obscure hurt,” as is so often the case in his fiction and letters, suffering becomes an opportunity not to recoil into the self, but to make contact with others, to feel a part of a wider system of relationships—one sympathetic observer, a circle of friends, a community, a nation. It is the cry of the single, sobbing woman in the street that is “the voice of history,” but only because she reenacts the experience of so many other grieving women down through the ages. That solitary cry and James’s experience of it, disseminated through writing, take on a richer significance and become expressive of a collective experience both of anguish and of empathy. So, when he made a claim for the validity and commonality of his own experience within that of the American nation during the Civil War, James also determined how he would position himself in 1914—as a register of the feelings of society, and as a conduit of impressions across some liminal zone between reality and published text. As Thomas Otten points out, James’s own pain during the Civil War allows him not to take sides, but to occupy “some place in between.”56 In 1914, this place was between participant and reader, between France and Britain, between Europe and America. In many ways this was, of course, exactly what he felt he had been doing for the last fifty years by observing and analyzing the experience of the individual, and aiming to communicate these to the reader. The role of the writer, as James defines it in “The Art of Fiction” (1884), is to move from the single to the general, or as he puts it “to guess the unseen from the seen, to trace the implication of things, to judge the whole piece by the pattern.”57

Despite the basic optimism of this approach to the role of the writer in wartime, many of James’s readers have found the extent of this desire to speak for others solipsistic or “self-aggrandizing.”58 However, these readings both exaggerate and underestimate the place of the Civil War in James’s imagination. In casting the old conflict and the “obscure hurt” as suppressed events in his psyche, it is all too easy to overlook the fact that it is James himself who first articulates and analyzes these complex connections. In his essay about the early stages of the war, “Within the Rim,” written in February 1915, James muses on the uncanny overlap of sensations with that earlier conflict. He felt that he knew “by experience” what the early excitement of war would bring: “The sudden new tang in the atmosphere, the flagrant difference, as one noted, in the look of everything, especially in that of people’s faces, the expressions, the hushes, the clustered groups, the detached wonderers, and slow-paced public meditators, were so many impressions long before received and in which the stretch of more than half a century had still left a sharpness.”59 This sense of recognition, he felt, saved him from any illusions about what might happen in northern France. Anyone who had lived through that earlier conflict “had known, had tremendously learnt, what the awful business is when it is ‘long,’ when it remains for months and months bitter and arid, void even of any great honour.” But he knew very well that the two wars were not the same, and the past is invoked in this essay not as a totem of security, but only to highlight the contrast with the present. All too swiftly, he felt, there was a moment “at which experience felt the ground give way and that one swung off into space, into history, into darkness, with every lamp extinguished and every abyss gaping.”60

Nevertheless, James’s own tendency to view the First World War through the lens of his experience of the Civil War does raise tricky questions about how he saw the balance between past and present and between the private and the public. It is tempting to trace a neat parallel between James’s resurgence of memories about the Civil War in 1914 with his decision to abandon work on The Ivory Tower, and restart work on his time-travel novel The Sense of the Past, as though James like his protagonist Ralph Pendrel had experienced some strange warping of linear time. Yet James’s ostensible jolt back to 1861 at the outbreak of the First World War is better understood as evidence of his continual sense of connection with the past. The Civil War was always with him. James had just spent two years reworking childhood recollections for his autobiography, patiently mapping out the mechanisms by which early experiences, including his impressions of that war, had formed his adult consciousness. There were also physical reminders of the old war. Every day in his study James worked to the rattle of the typewriter which bore the name of the Union Army’s rifle maker, Remington. Burgess Noakes recalled that even James’s trousers “were held up by an old belt from the American Civil War. His cuff-links were miniature cannons.”61 These unexpectedly military accessories were probably inherited from James’s younger brother Wilky, who, serving as an officer in the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts, was critically wounded in the disastrous attack on Fort Wagner in 1863. Brought home to Newport by the father of a fallen fellow officer, Wilky, barely eighteen years old, hovered close to death for days, lying in the hallway of the family house on the stretcher which had carried him home. The doctor pronounced him too ill to be moved. He struggled back to action, but his health never fully recovered, and he died in 1883, in his late thirties. James had not forgotten. Like the severed limb, the image of the wounded body was a powerful one for him, not glibly employed.

As the glorious late summer of 1914 waned into October, Rye suddenly felt lonely, and James shifted camp to his flat in Chelsea, where he usually spent the winters. He found London “agitating but interesting,” at times even “uplifting,” but he was frustrated by the limited range of things he could do. “To be old and doddering now,” he wrote to Rhoda Broughton, “is for a male person not at all glorious.”62 He did a little writing, but unusually James felt that the drama was outside these days, not in the imagination, and he was finding it compelling to watch. He wrote to his childhood friend Thomas Sargeant Perry that there was something “that ministers to life and knowledge” in the “collective experience, for all its big black streaks.”63 He found small but meaningful activities. He wrote anxiously to Noakes, sending chocolate and socks. He visited Belgian refugees at Crosby Hall, in Cheyne Walk where he lived. This grand, old, fifteenth-century building had been moved from its original site at Bishopsgate in 1910 to save it from demolition, and to James’s mind there was a poetic symmetry in the way that this salvaged, dislocated construction should offer shelter to those in such a similar position. He was also empathetic enough to wonder what it must be like to find oneself in “some like exiled and huddled and charity-fed predicament.”64 He visited wounded soldiers at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital—at first the Belgians, to whom he could speak French, but increasingly the wounded British, whom he found “even more interesting.” They struck him as “quite ideal and natural soldier stuff of the easy, the bright and instinctive, and above all the, in this country, probably quite inexhaustible kind.”65 But even this immediate confrontation with the consequences of the modern conflict raised ghosts from the Civil War. He remembered how with Perry he had visited a vast, tented hospital in Portsmouth Grove, Rhode Island, and had mused then, as he did again now, on the “alternative aspect” of the soldier lying helpless in a bed, “the passive as distinguished from the active” side of the fighting man.66 When he had recorded this visit some months before in Notes of a Son and Brother, he had rejoiced in the way his own youthful experience coincided with that of Walt Whitman, moving tenderly among the wounded of the war, armed “with oranges and peppermints.”67 At St. Bart’s in 1914, as an old man talking to the stricken young, the comparison with Whitman must have struck James even more forcefully. What the soldiers felt about the great novelist’s slow and solicitous conversation no one will ever know.

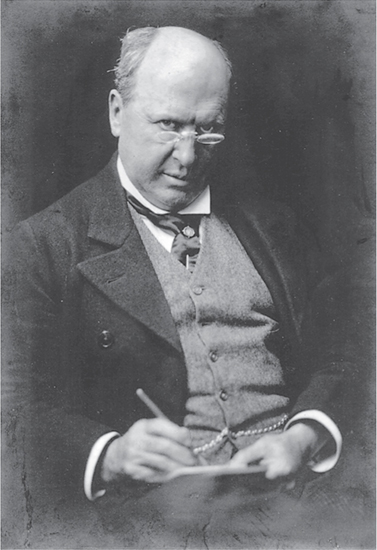

1. Henry James in the years before the war. Photograph by Katherine McClellan, courtesy of Smith College.

Tintner cites James’s “growing homoeroticism,” evident in his admiration for the young men around him, as one of the reasons for “exposing himself and his feeling to public scrutiny” during the war, and this has become a widely accepted reading of James’s war history.”68 However, it seems a faulty use of logic to present this latent desire, whether conscious or suppressed, as the root motive of James’s political and literary response to the war. He did enjoy the sight of handsome youths in uniform, and he did believe in the war effort, but that one was the cause of the other is questionable. In his study of touch and intimacy in the war zone, Santanu Das cautions against the “anachronistic” tendency to mark as definitively homoerotic those statements and actions—even apparently explicit actions such as the same-sex kiss—which, when restored to their wartime context, overlap with other deep human instincts such as “sentimentalism, tenderness and aestheticism.”69 James’s devotion to his wounded soldiers is similarly difficult to decode. It is perhaps safer to say that James’s sexuality, mysterious as this question remains to scholars of his life and work, was only one factor among the many forces propelling him into the public eye in 1914.

James’s motives are difficult to fathom. Knowing what we now know about the First World War, his enthusiasm for action and his ever-increasing desire for America to join forces with the Allies seem profoundly out of character for this thoughtful, tolerant, often hesitant man. In 1914, however, social attitudes to war, as to sexuality, were very different to those of the present day. Patrick Devlin notes that “international morality” (a phrase that in another context might sound like the stuff of James’s transatlantic fiction) accepted war as a means of settling political differences, but also strictly governed the terms of engagement, protecting the rights of civilians and of neutral nations.70 The full horror of a “total war” in which civilians and conscripts were the hapless victims of large-scale tactical experiments had not yet been unleashed upon the world, and with his limited access to information about the reality of the front, James was neither unreasonable nor hysterical in imagining during the early phases of the conflict that military force was a workable and noble response to events. Most people in Britain thought the same. Nor was James’s response to the war as fixed as it is often portrayed; in truth, his opinions swung around from week to week, and varied subtly in response to different correspondents. As Chapter Two discusses, his essays and letters reveal a mind moving swiftly to accommodate new ideas as they emerge, to employ his imagination and his powers of empathy, to face up to the bewildering scale of the human loss involved, and to find possibilities of creativity in the darkest elements of the conflict. For James, the First World War was about much more than his own emotional baggage.

Through his friends in the political class, such as Edmund Gosse, who was a close friend and advisor to H. H. Asquith, and Edward Marsh, currently private secretary to Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty, news of James’s enthusiasm for the British cause reached Downing Street. Margot Asquith, the prime minister’s wife, invited James to lunch, where he found himself suddenly immersed in the inner circle of British leadership. He became a regular guest, but as he wrote to Thomas and Lilla Perry, it was “idiotic” to imagine that lunching with Asquith would allow him “the chance to catch some gleam between the chinks” of the tight controls on public information about the war, “because it’s mostly in those circles that the chinks are well puttied over.”71 Nevertheless, he quickly became a close friend of the Asquiths, and was invited to spend a weekend with them at Walmer Castle in Kent in January 1915. Winston Churchill was also present—young, impatient, and sardonic. As James left, he told Violet Asquith, the prime minister’s daughter, that it had been “a very interesting experience to meet that young man.” It had, he said, brought home to him “very forcibly—very vividly—the limitations by which men of genius obtain their ascendancy over mankind.” Reaching for a phrase that Churchill himself might have used, James added, “It bucks one up.”72

There were other experiences that he found equally stimulating, experiences that balanced against the horrors of war and the moods of depression that increasingly swept over him. To a man who had dedicated much of his literary life to dramatizing pluralized viewpoints, his new-found sense of moral and political conviction was oddly exhilarating. Britain seemed to be in “so magnificent a position before the world, in respect to the history and logic of her action,” that it came as a surprise to him “to find one can be on a ‘side’ with all one’s weight.”73 He went often to visit Walter Hines Page, the American ambassador to London, in the afternoon, and they had long talks together about the issue of American neutrality. He wrote to Elizabeth Norton that he found himself “sickened to the very soul” by the “louche and sinister figure of Mr Woodrow Wilson, who seems to be aware of nothing but the various ingenious ways in which it is open to him to make difficulties for us.” It was not at all clear whether by “us” James meant those Americans who believed military action was justified or the Allied nations. Swept up as he was in the “rightness” of the Allies’ cause, appalled by the loss of “such ranks upon ranks of the finest young human material,” and convinced that America held the power to shorten the war by intervention, James had little patience with Wilson’s diplomacy, which projected “the meanness of his note as it breaks into all this heroic air.”74

But politics was never James’s métier. He was fascinated by the drama and the intensity of the relationships between the men of power, but it was the question of the personal significance of the war, and how the artist could possibly respond to this which taxed his imagination most.75 In early August 1914, he had written to Esther Sutro, wife of the dramatist Alfred Sutro, that he intended to keep writing throughout the conflict, despite the smell of blood and gunpowder in the inkpot. James asked her to tell Alfred, “that I hold we can still, he and I, make a little civilization, the inkpot aiding, even when vast chunks of it, around us, go down into the abyss.”76 By October, as his own work schedule began to flag, and he became aware of the imaginative difficulties of forming fiction in wartime, he wrote to his American publisher Charles Scribner, with another military metaphor, to explain that it was all he could do to “pretend just to keep in the saddle, sitting as tight as ever I can.” Nevertheless, James was beginning to sense that the destructive force of the war also held a strange new kind of creative potential. As he told Scribner, “Those of us who shall outwear and outlast, who shall above all outlive, in the larger sense of the term, and outimagine, will be able to show for the adventure, I am convinced, a weight and quality that may be verily worth your having waited for.”77 Of course, this may merely have been James’s eloquent way of negotiating an extension to his deadline, but, by December, he was writing to Scribner once more, explaining that however horrible the conflict was, there was something “infernally inspiring” about it. James felt that “after the first horror and sickness, which are indeed unspeakable, Interest rises and rises and spreads enormous wings,” like a great vulture circling in search of the “terrible human meaning” of the war. “It is very dreadful,” he wrote, “but after half dying with dismay and repugnance under the first shock of possibilities that I really believed had become extinct, I began little by little, to feel them give an intensity to life (even at my time of it) which I wouldn’t have passed away without knowing.” He added, “Such is my monstrous state of mind.”78

As 1914 drew to a close, James felt ready to publish some of his thoughts on the war. He had done little polemical writing in his long and prolific career, and had not written on international politics since the late 1870s, but he felt it was now time to make a public gesture. In November, over lunch with Richard Norton, he offered to write a fund-raising letter for the ambulance unit, describing its work in France and appealing for funds from the public on both sides of the Atlantic.79 Five days later it was finished, and was published in London as a pamphlet by Macmillan with the sober title The American Volunteer Motor-Ambulance Corps in France: A Letter to the Editor of an American Journal. However, it appeared in New York World, on 4 January 1915, with the more dashing heading: “Famous Novelist Describes Deeds of US Motor Corps.” James may have been appalled or flattered at this decision to trade on his literary reputation—possibly both—but it demonstrated, as the letter read to the Académie Française had done, that his name still carried enough cache to draw some public attention. It is an unusual piece of writing in James’s oeuvre. It was clearly produced at speed, and compared to much of his late work, the tone is raw and unfamiliar, although his distinctive intellectual signature is there in his satisfaction at the idea that “the unpaid chauffeur, the wise amateur driver and ready lifter, helper, healer, and, so far as may be, consoler, is apt to be an University man,” trained to assimilate and appreciate “the beauty of the vivid and palpable social result.”80 This may have sounded snobbish, but as the following chapters will show, it demonstrated just how shrewd James was about where and how literary responses to the war would originate. The university men of the ambulance services would turn out to be some of the finest writers of their generation. Even when considering the harsh realities of life behind the front, James was determined to see the war in terms of its aesthetic and cultural impact. In reviewing this pamphlet, the British Medical Journal paid tribute to what it called “the testimony of a neutral” in corroborating stories of the German army firing on ambulances in contravention of the Geneva Convention—although, to describe James as “neutral” would not, by this stage, be strictly accurate.81 The most startling feature of this article is the way in which James again experiments with his use of the third-person plural: “we nevertheless pushed on,” he writes, as though he was riding in the passenger seat of a converted Model-T through the fields of northern France.82 He did so in his imagination only, but his sense of who “we” were, and how one could shift one’s identity with so small a word was evolving apace.

After the war, Percy Lubbock would write that in those early days Henry James had provided what everyone lacked: “a voice; there was a trumpet note in it that was heard nowhere else and that alone rose to the height of the truth.”83 But James’s voice was speaking with an increasingly British accent. Although still an American citizen, there was no escaping the fact that James, over his many long years in London and Rye, had fallen out of step with many of the changes and demographic shifts in American cultural life—a disjunction that he himself had recognized so vividly during his American tour of 1904–5, and analyzed so minutely in The American Scene (1907). Partly as a result of James’s own work, and that of others in his generation such as Mark Twain and William Dean Howells, American literary life had acquired a depth and variety by 1914 that would have been hard to imagine even twenty years before. In the 1890s, Boston stood unrivaled as the publishing and intellectual hub of the nation, but by the early years of the new century its intimate, educated atmosphere, which James had found so stifling as a young novelist, was already giving way to new subjects, new styles, new names on flyleaves—many of them foreign-sounding to old New England ears: Theodore Dreiser, Kate Chopin, Gertrude Stein, W. E. B. Du Bois. New publishing houses and new literary and political journals sprang up apace in New York, Chicago, and San Francisco. Midwest and West Coast lifestyles began to feature in the work of writers such as Willa Cather, Ellen Glasgow, Frank Norris, and Upton Sinclair. It was a very different world from that of James’s youth—a world of railroads and telephones, of industrial-scale farming, meat packing, sweat shops, sharp business, theatrical glamor, and political unrest. This too was America.

Like personal motives, however, changes in culture are complex, and are often characterized by interfusion as much as by opposition. Many writers of this new generation were a curious blend of convention and experiment, of hesitation and daring—none more so than the poet Grace Fallow Norton (1876–1962). Norton’s life story has never been told outside of her family circle, and her work is not well known. Much of it belongs to the pre-war tradition of “genteel” verse—a style rarely appealing to present critical tastes. However, this was the predominant mode of poetic consumption in prewar America, by a readership that still revered the rhythms and abstractions of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, read the lyrics of Julia Ward Howe and Josephine Peabody with delight, and found the formal innovations of Emily Dickinson—let alone Walt Whitman—something of a puzzle. As Van Wienen notes, “genteel” has slipped into critical usage as a term which encompasses all “nonmodernist” verse from the early decades of the twentieth century and elides the variety and caustic intensity of these texts, which often provided powerful vehicles for political debate and dissent throughout a turbulent period of American’s history.84 In reality, the use of traditional forms and diction by such poets was often contrasted with unconventional perspectives, daring material, and very un-genteel judgments on society. Norton deserves more attention than she gets for a number of reasons. As a Midwestern, middle-class, college-educated American who had by 1914 traveled widely in Europe, developed liberal views, and immersed herself in the cultural life of bohemian New York, she offers a valuable view of the reactions of the intellectual and creative communities to the war. Caught in Brittany when the fighting broke out, like many other American visitors she fled home, watching events in Europe unfold from a distance with a frustration that found an outlet mostly through words. There are flashes of structural daring in Norton’s poems about the war, challenges to the traditional forms of rhyme and meter, which point forward to the innovations of later poets such as Cummings, Borden, and MacLeish. However, her work, like that of the soldier-poet Alan Seeger, more often shows what was possible (and sometimes what was not) within the boundaries of conventional verse.

James might have provided a voice that offered a “trumpet blast.” Norton, on the other hand called the American reader’s attention to the eerie quiet that the war created in French provincial life. Her long, moving two-part poem about the outbreak of war, “The Mobilization in Brittany,” both begins and ends in silence:

It was silent in the street.

I did not know until a woman told me,

Sobbing over the muslin she sold me.

Then I went out and walked to the square

And saw a few dazed people standing there.85

After the drums and the bells and the shouting and the crying, and the troops at the station singing the Marseillaise, there is silence again and a question that no one can answer:

The train went and another has gone, but none, coming, has brought word.

Though you may know, you, out in the world, we have not heard,

We are not sure that the great battalions have stirred—

Except for something, something in the air,

Except for the weeping of the wild old women of Finistère.

How long will the others dream and stare?86

The poem’s speaker concludes in resignation, “So this is the way of war.” Here, it is not the battlefield that defines war, but the quiet despair of ordinary lives disrupted. The irregular lines, the interrupted metrical patterns and the uncomfortable juxtaposition of harsh contemporary detail and dreamy idealism in her work, show Norton to be a poet working hard to adapt the rules of her craft to the unsettled, distressing mood of what she has witnessed. This is poetry with a backstory.

Norton’s wartime experience—especially the chain of events by which the publication of her anthology What Is Your Legion? (1916) became caught up with the campaign by many in the intellectual classes for American intervention—illuminates the means by which writers, and their publishers and distributors, used their work to attempt to shape events around them. This attempt has often led to such work, like James’s essays, being characterized as propaganda. However, this term—which in 1914 did not carry such strong overtones of deliberate political deception as it does now—oversimplifies the relationship between literary and political activity, particularly before April 1917. When one considers that much material now labeled as “propaganda” was written in criticism of the U.S. government, and distributed (as Norton’s anthology was) in defiance of obstructions to the expression of public opinion about the war, this issue suddenly seems less straightforward.

Grace Norton was born on 29 October 1876 in Northfield, Minnesota, and grew up in a family of strict Congregationalists affluent with money made in local banking. Orphaned by the age of ten, Grace was raised by a succession of aunts and uncles until her older sister Gertrude married Fred Schmidt, an Episcopalian from nearby Faribault, regarded by Norton’s family as something of a “mythical sin-city,” who banished the censorial relatives from the family home.87 Gertrude and Fred embraced new ideas—a few years later, they would buy the first automobile in Northfield—and they encouraged Grace in her musical and literary enthusiasms. She was sent to Abbot Academy in Andover, and took piano lessons in Boston in defiance of her Norton and Scriver uncles, who thought classical music a dangerous worldly pastime. The Schmidts, however, arranged for Grace to travel in Europe, staying with Fred’s relatives in Switzerland, visiting Norway, and studying piano in Berlin.88 She returned to America in the spring of 1899, and settled in New York City, struggling to make a living as a piano accompanist, and trying to get her poetry published. She once confessed that during this time she was so poor that her main source of income was making marbled endpapers for publishing houses.89 But life was vivid and full of new contacts. She mixed with writers, painters, academics, and activists, and her friends ranged from the respected publisher Thomas Bird Mosher to the anarchist Emma Goldman. By 1909, she was married to Herman de Fremery, a curator at the Natural History Museum, and living uptown in 177th Street. In 1911, she traveled to France to stay with her husband’s relatives. Here, she read avidly, soaking up Guy de Maupassant, Paul Bourget, and Théophile Gautier, “trying to learn the secrets of French poetry.”90 She began to write in earnest, and around this point also changed her name, not to Mrs. de Fremery, but to Grace Fallow Norton, adding the middle name partly for the sound, and also to distinguish herself from Grace Norton of the Cambridge Nortons, whose book Studies in Montaigne was published in 1904.

From 1910 until the late 1930s, Grace Fallow Norton’s poetry appeared in respected literary journals such as the Atlantic Monthly and the Century Magazine, Scribner’s Magazine, Harper’s Monthly Magazine, McClure’s Magazine, Poetry Journal, and Poetry. She struck up a good working relationship with the Boston publishers Houghton Mifflin, especially the editor and author Ferris Greenslet, who would remain her contact at the firm until 1927. In 1912, Houghton Mifflin published Norton’s first anthology, Little Gray Songs from St. Joseph’s, a series of poems about a young girl dying in an American convent. According to the New York Times, the little book was “a revelation of what genius can do with the ordinary and every-day things of life.”91 Modern readers find these poems sentimental and static. But there was something that caught the public imagination in Norton’s selection of pain as a subject for verse, and there is a haunting, Dickinson-like quality in her plain vocabulary and in the simplicity of structure. This volume established Norton as a rising writer of promise, someone to watch in the coming years. Amy Lowell would list her in a group of noteworthy poets including Ezra Pound and Nicholas Vachel Lindsay: “poets with many differing thoughts and modes of thought,” whose work demonstrated “the great vitality of poetry at the moment.”92 Houghton Mifflin quickly commissioned a second volume of verse.

However, just as Norton’s career seemed to be blossoming, her personal world collapsed. No sooner had she dedicated Little Gray Songs to “H. de. F.,” than their marriage broke down. In the spring of 1912, de Fremery began a relationship with Henrietta Rodman, a high school English teacher. Sometime in the same year, Norton also began a new romance with the young, controversial painter George Herbert Macrum. Divorce proceedings followed, and in February the following year de Fremery and Rodman were secretly married.93 Macrum, an art student from Pittsburgh, two years younger than Norton, had already caused a stir by daring to exhibit a painting of a nude woman at a students’ art exhibition in 1906.94 He would later make his mark as a specialist in landscapes and urban scenes and would exhibit at a number of distinguished galleries and exhibitions, including the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Pennsylvania Academy, the Corcoran Gallery, and the Appalachian Expo at Knoxville, Tennessee, where he took a gold medal in 1911. His paintings nowadays change hands for up to ten thousand dollars—money that would have been bewilderingly welcome to Norton and Macrum during the coming years.

After the marriage, Norton completed The Sister of the Wind (1914), a substantial, second collection of poems, many of which dealt with the emotional upheaval of the previous months, and which also included her best-known poem “Love Is a Terrible Thing.” Like so many of her works, this lyric concludes with a cry for personal freedom: “Oh, would I were free as the wind on the wing;/Love is a terrible thing.”95 By the time this book was in print, however, Norton and Macrum, now married and traveling as Mr and Mrs. Macrum, had left America. In May 1914, they sailed to Hamburg on the Pennsylvania, with plans to visit Paris and Brittany. Norton wrote to Greenslet from the boat: “Such a chance at France! I intend the most thorough intoxication. Anything less would be utterly ungrateful. … All repressed, strangled and mangled ex-Puritans should take the French bath.”96 Associated on the one hand with treasured rebellions from her family upbringing, and on the other with the sense of release and rejuvenation that accompanied her new relationship with Macrum, France appeared to Norton a haven of style and creativity. As she wrote to Mosher, “It’s in the Touraine or in Bretagne that I’m hoping my tongue will blossom without thorns.”97 She arrived with plans for a third volume of verse, and in July, the couple took a house for three months in Plomarche, near Finistère, where Macrum could paint in the clear light of the Brittany coast. Like most other travelers in France that summer, they had very little warning of what was about to happen next.

When mobilization was announced on 1 August, Norton was stunned out of her creative reverie, into sharp observation of the situation of the French people around her. Watching the grim enthusiasm for war and the overnight militarization of what had seemed a peaceful and placid corner of provincial France, Norton was both appalled and fascinated at the transformation. It prompted a series of nine poems, which initially seemed to her a distraction from the set of lyrics about moods and colors which she was working on for Greenslet: “Is This the End of the Journey?”; “The Mobilization in Brittany”; “The French Soldier and His Bayonet”; “The Journey”; “In This Year”; “The Volunteer”; “Cutting, Folding and Shaping”; “On Seeing Young Soldiers in London”; and “O Peace, Where Is Thy Faithful Sentry?” These poems would later find their ways into that same anthology, Roads, as a section on the conflict entitled “The Red Road.” It contains some of her strongest work. All trace of sentimentality drops away from her poetic style as she adopts the rough rhythms of the ancient ballad form in an uncompromising portrait of the husband-turned-fighter:

The French Soldier and His Bayonet

Farewell, my wife, farewell, Marie,

I am going with Rosalie.

You stand, you weep, you look at me—

But you know the rights of Rosalie,

And she calls, the mistress of men like me!

I come, my little Rosalie,

My white-lipped, silent Rosalie,

My thin and hungry Rosalie!

Strange you are to be heard by me,

But I keep my pledge, pale Rosalie!

On the long march you will cling to me

And I shall love you Rosalie;

And soon you will leap and sing to me

And I shall prove you Rosalie;

And you will laugh, laugh hungrily

And your lips grow red, my Rosalie;

And you will drink, drink deep with me,

My fearless flushed lithe Rosalie!

Farewell, O faithful far Marie,

I am content with Rosalie.

She is my love and my life to me,

And your lone and my land—my Rosalie!

Go mourn, go mourn in the aisle, Marie,

She lies at my side, red Rosalie!

Go mourn, go mourn and cry for me.

My cry when I die will be “Rosalie!”98

This uncompromising poem gives a sophisticated reading of many of the racial and gender stereotypes which fuel the business of war. Not only does Norton step into the shoes of the male combatant speaker of the poem, thus abandoning a passive, observing, traditionally feminine perspective; she also appropriates that most phallic of weapons, the bayonet, and personifies it in female form. Here, Norton plays on the name of “Rosalie,” the soldier’s nickname for the bayonet issued by the French army, a slim, cruel, stiletto-like blade, designed for hand-to-hand fighting in the trenches. The form of the poem carries military echoes too. Its four-foot line with the mix of iambic and anapestic rhythms mimics the relentless tramp of a traditional marching song, driven forward by direct speech and repetition. However, Norton is not only appealing to the patterns of the past. “The French Soldier and His Bayonet” is also a response to the contemporary French song “Rosalie,” by Théodore Botrel, a popular singer of the belle époche. Botrel’s lyrics, which came to prominence in the fall of 1914, celebrate the French “cult of the bayonet,” eroticizing the relationship between soldier, bayonet, and victim in complex and disturbing ways:99

Rosalie est élégante

Sa robe-foureau collante,

Verse à boire!

La revêt jusqu’au quillon

Buvons donc!

Rosalie is elegant

Her sheath-dress tight-fitting,

Pour a drink!

Adorns her up to the neck.

Let us drink, then!100

The many verses of this song, which Botrel performed regularly through the war at French military camps during government-sponsored entertainments, explore the sexual connotations of wielding such a weapon: as a rape, as a seduction, as the release of the heady red wine of the victim’s blood. Botrel’s song plays on the French verb piquer, which means both to pierce and to excite or stimulate, but under the surface, there is also a cultural anxiety about the seductive power of women, and a need to distance the soldier psychologically from the act of killing; through this metaphor, the grisly, intimate act of stabbing can be displaced and seen as the action of the personified, female blade instead. Regina M. Sweeney notes that Botrel’s song was much imitated during the war, leading to a whole subgenre of “Rosalie” songs, matched by similar lyrics about “Mimi” the machine gun, or “Catherine” and “Nana” the field guns.101 Yet, the bayonet appears to have had a particularly vivid place in the French imagination. It was referred to as “the soldier’s wife,” perhaps because it stood by him when all else had failed. La Baionette was also the title of a French wartime journal, which published reports and polemics about the war, designed to rouse national feeling against Germany. Rosalie the bayonet was a powerful symbol of French patriotism, defiance, and hot-headed gallantry.