1 Introducing South Asia, Re-introducing ‘Religion’

‘South Asia’ is the name given to a region that includes the modern nation-states of Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and the Maldives. Together, these countries constitute an enormous area of the world, home to a population of roughly 1.6 billion people, about 23 per cent of humanity. It is an area that has, for centuries, been strategically significant in global geo-political terms, the site of many empires, and a critical global trade arena since at least the first millennium BCE. In the contemporary era, it is distinctive as a region where you will find, in the Republic of India, one of the fastest-growing and most powerful economies in the world. At the same time, it is one of the world’s poorest regions; World Bank figures indicate that in 2005 more than 40 per cent of the population across the region lived on less than $1.25 per day (World Bank 2011: 66). It also hosts two of the world’s nuclear powers (India and Pakistan).

South Asia is, then, a region of great significance in the contemporary world. Our objective in this book is to provide some insights into one important feature of the region: its religious traditions. It is a commonplace to say that South Asia is a region of great religious diversity (see Box 1.1). In this book we want to investigate what this well-worn phrase actually means, by exploring the development of its religious traditions in a range of social and political contexts.

Box 1.1 Enumerating Religion in South Asia?

These figures and quotations are drawn from the US Department of State’s (2010) ‘Annual Report to Congress on International Religious Freedom’. As you can see, the ability of the report to provide accurate figures is variable, as in some nation-states the exact religious identity of citizens or subjects has not been established. Where accurate figures are provided, they are generally based on 2001 census statistics gathered by the respective nation-states.

Even where census data has been gathered, the diversity that is hidden by labels such as ‘Hindu’ and ‘Muslim’ means that the language of accuracy and exactness can be misleading. As we shall see in this book, the way that religious identity is actually lived out can contradict the apparent order and stability that such figures seek to represent.

In the broadest sense, these contexts are configured by the region itself. Its seven independent nation-states define South Asia geographically by their position on or adjacent to the Indian subcontinent. South Asia has also been defined by its historical link to the British empire, dominant in this region during the nineteenth and first half of the twentieth centuries. On this view, we should include Burma (Myanmar) within South Asia, as it formed part of the administrative unit known as British India. We could, however, also exclude Sri Lanka, which was administered separately during the colonial period. Alternatively, if we included modern nation-states that have cultural continuities with an earlier Indian empire, the Mughal empire, we might look to the area of Persian influence and include modern Afghanistan and even Iran in our subject matter. Certainly Afghanistan has, in more recent years, been increasingly drawn into the region, as indicated by its membership since 2007 of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC). What these points demonstrate is that South Asia, rather than being a fixed entity, is a conceptual construct that changes according to the contexts in which it is located.1

As with the region, so with its religious traditions! They are also, we argue, constructed differently in different contexts. Under such circumstances, attempting comprehensive coverage of these traditions would appear a dubious enterprise; it is not one we will attempt in this book. Our intention, rather, is to supply you, the reader, with a range of perspectives and diverse examples and so, we hope, provide a critical and thought-provoking method for studying religious traditions in modern South Asia.

You may already have noted the play on ‘tradition(s)’ and ‘modernity’ in our title. This partly reflects our desire to trace the continuities as well as the changes that have shaped understandings of religion in the modern era. It is also a challenge, an initial encouragement to reflect on such categories. Religion is often presented as the traditional antithesis to the inexorable secularity of modernity. Our hope is that this book will question such neat assumptions, demonstrating, rather, that the categories through which we understand the world around us are continually and mutually constructed. ‘Tradition’ and ‘modernity’ are two such categories. ‘Religion’ is another.

So one of the tasks we have set ourselves in this first chapter is to ‘reintroduce’ religion within such a critical framework, as a prerequisite for our exploration of South Asian religious traditions.2 Before turning to this task, however, we want to provide some perspectives on the region itself, to situate it in space and time. As with our broader project in this book, we do not attempt to provide a sense of totality; rather, we give a series of specific ‘snapshots’, brief views of a vast, multi-dimensional (and indeed limitless) terrain.

Situating South Asia 1: Landscapes of Diversity

Fly then from the Himalaya mountains in the north down the west coast of India to the southern town of Kochi (Cochin) in the state of Kerala. Engaged in trade with the Mediterranean, Arabia and the Persian Gulf from Roman times onwards, and later used as a staging post for trade to China, this coast of southwest India has enjoyed cosmopolitan status for centuries. A swift look around the small district of Mattancheri in Kochi confirms this history and its impact upon religious traditions in South Asia. Just north of Jew Town Road stands the Paradesi Synagogue, founded in 1538 and rebuilt in the eighteenth century – the synagogue for ‘foreigner’ traders or White Jews as they were known. By contrast, the so-called Black Jews, long-time Indian Jews whose ancestors married Jewish traders from perhaps as early as the sixth century CE, were deemed in the Paradesi Synagogue to have lower status. This alerts us that issues of social status cross-cut religious allegiance here as elsewhere in the world. Since 1948, the majority of Cochin Jews have emigrated to the modern state of Israel, having lost their political privileges when the Princely State of Cochin became part of Kerala in 1947 (Gerstenfeld 2005). They do not show by religion on the 2001 census. In the past, though, local Hindu rulers acted as patrons to Jews (as well as Christians and others), giving financial support and guaranteeing their right to practise their own traditions. The ability of different groups to ‘slot’ into local social relations has been an important factor in shaping religious traditions in South Asia.

Right next door to the synagogue is the Dutch Palace, first built by the Portuguese in 1555 for the Hindu Raja of Cochin. Now a museum, within its walls is the still-functioning Pazhayannur Bhagavati temple, to the Goddess of the rulers of Cochin, alerting us to the idea that state and religion may be closely connected. Another wall of the synagogue is shared with a temple to Krishna, a different deity. Later in the book, we shall ask about the relations between such temples and deities. Part of the answer may be to do with the places from which different groups have migrated. To the west and north of the synagogue is an area now largely inhabited by people from Gujarat and Kutch in northwest India, who have settled here again largely as the result of trade links. During the Navratri nine nights festival to the Goddess in September/October, the Dariyasthan temple is full of Gujaratis dancing the dandiya, a lively stick dance that they have brought with them and taught their children. They are probably mainly Lohana, belonging to a particular trading caste, temples (and deities) being sometimes linked with caste groups as well as regional leanings. This is the case with churches too. Following the road from there north, you will come across a Gujarati school, reminding us of the importance of retaining one’s own language* when surrounded by neighbours who speak a different one, here, Malayalam. Perhaps 400 metres along the same road, you will see the Cutchi Memon Hanafi Mosque, its name aligning its community with an area spanning the India/Pakistan border (Kutch), a particular group of Muslims (Memons) and one of the four main branches of Islamic law (the Hanafi). They will share a language (if not the exact dialect) with those who dance at the Gujarati temples nearby, as well as with worshippers at the big Jain temple lying between the mosque and the Gujarati school. This Bhagwan Shri Dharmanath Jain temple, built in 1904, represents another migration from Gujarat, going back perhaps to the early nineteenth century. Now its website proclaims proudly its place in the pluralistic microcosm of Mattancheri, ‘Mini-India’. We have started to see why.

The Ernakulam district in which Mattancheri lies is also diverse. It had as many Christians as Hindus according to the 2001 census. Although some churches in this area date back to the influence of Portuguese Catholics from the sixteenth century, there were Christian communities in this part of India from as early as the second century, as we know from Roman sources (even if there is no hard evidence for the story that St Thomas, one of Jesus’ twelve disciples, himself came to south India). The history of Christianity in India therefore predates that in, say, Britain by at least a couple of centuries, that in America by over a millennium. When we look at religious traditions in modern South Asia, we need to keep this history of diversity and change in mind.

Now fly over a thousand miles northeast. You will come to a sprawling megacity. Not Kolkata (Calcutta), in West Bengal, the colonial capital of British India until 1911, and fifth largest city in the world (13,217,000 population in the 2001 census), but Dhaka, the capital of modern Bangladesh, East Bengal, with a current population of over 10 million. In this great ‘City of Mosques’, straddling the banks of the River Baraganga, just over 10 per cent of its population are Hindus. Sometimes, major Muslim and Hindu festivals coincide, leading to extended celebrations in the city.3 In 2007, for example, Eid ul-Fitr fell in October. Each Eid, between 7:30 and 10:00 A.M., Dhaka’s 360 specified Eidgahs (Eid grounds) and mosques are packed with Muslims saying their Eid prayers, with special provision made for women. Dressed in colourful new clothes, people visit family and friends, and share Eid delicacies and sweets. In 2007, in the days that followed, Hindu neighbours celebrated Durga Puja, the biggest festival of the Bengali Hindu year. Visit Shakari Bazar and women are walking in brightly coloured saris just like those of their Muslim counterparts at Eid, twenty temples packed into the sixty metres or so of this old Hindu street with buildings three or four storeys high going back deep from the narrow road. Pandals (pavilions) for the Goddess Durga are set up, neighbours visited, sweets enjoyed. A Muslim writer, Fakrul Alam, remembers Eids and Durga Pujas in the 1960s of his childhood, when Hindu and Muslim friends and families would exchange sweets and share one another’s festivities in the Ramakrishna Mission area of Dhaka. Now his young nephew does not go inside puja pandals. ‘We aren’t supposed to’, he says (Alam 2007). But the government takes measures to ensure both festivals pass off peacefully, stressing that Bangladesh protects the religious rights of all.

Northwest a further thousand miles lies the village of Dadyal, Hoshiarpur District, Punjab, India (Figure 1.1). Affected, like Bengal, by the partition of India and Pakistan in 1947, the villages in this area are now Sikh and Hindu. Muslims fled over the border into Pakistani Punjab.4 Yet on a Thursday evening in this area, women, men and children from the villages will gather at Sufi shrines to offer their respects to the pir or holy man in the place where he was united in ‘marriage’ with Allah at death. Then they will stay for the langar (meal), sitting in rows on the ground, sharing food offered to all who come. Just outside Dadyal village itself is the shrine of Baba Hasan Das. He bears a Muslim name (Hasan), is worshipped by Sikhs and Hindus, offers cures to any who come to the place under a tree where he used to meditate, and now has his picture in the gurdwara, alongside the Guru Granth Sahib (Figure 1.2). Nearby, the village temple to the Hindu deity Shiva lists donations from both Hindus and Sikhs, many from the UK, especially from Leicester, where a blogger notes a langar for Baba Hasan Das is held in one of the Sikh gurdwaras (Randip-Singh 2007).

Figure 1.1 Dadyal village across the tank. Reproduced courtesy of Roger Ballard.

Figure 1.2 Inside the gurdwara: Baba Hasan Das (left of our picture) and Guru Gobind Singh (right) with Guru Granth Sahib and Dasam Granth on twin palkhis. Reproduced courtesy of Roger Ballard.

Our final port of call, a mere hop of around 300 miles southwest, is in the heart of the ‘cow-belt’, the area of Uttar Pradesh in north India where Hindu identity is particularly strongly emphasized. Mathura, on the river Yamuna, is renowned as the birthplace of Lord Krishna. In the holy area of Vraj (Braj), where Krishna played with the gopis (the girls who looked after the cows), he is believed to play still with those who have eyes to see. Yet in this area, different local traditions have jostled since the time of Gautama Buddha, who is supposed to have commented that Mathura was overrun with devotees of the Yakki (Yaksha) cult, semi-divine beings associated with the earth and trees. In Mahaban, for example, a village of largely low-caste people and Muslims, the cult of Jakhaiya is run by Sanadhya brahmins, but preserves some very non-brahmin Yaksha rituals, involving a rooster and a pig that in the past would have been sacrificed. Now the pig’s blood is offered to the earth from a cut made in its ear.

Local stories also bear testimony to contestation and negotiation between particular groups of brahmins who moved into the area from the sixteenth century onwards, when Krishna devotion really started to flourish here. Different sites and forms of devotion were legitimated from the mouth of Shree Nathji himself (Krishna), devotees of the Vallabha Pushtimarg tradition and the Bengali Chaitanya tradition telling the same story very differently (Sanford 2002). As in the other places we have visited, you can find in Mathura an imposing mosque among the many temples and wayside shrines. Yet alongside manifestations of Hinduism and Islam, the paths of ancient ritual, multiple traditions and renegotiated pilgrimage routes run deep.

Situating South Asia 2: Snapshots of History

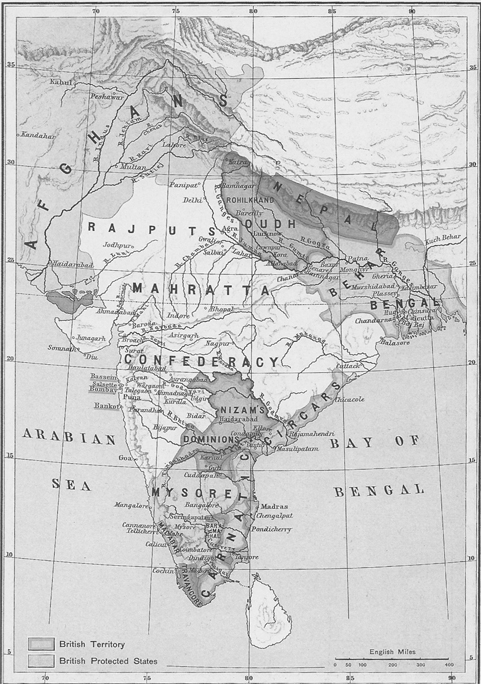

We now turn from space to an exploration of South Asia in time. In the course of this book, we will be looking at particular historical moments in some depth, especially in Part II. Here, we offer a series of snapshots of South Asian history. These help us to map our landscapes of diversity further. For maps, of course, exist in time as well as space. Consider, for instance, the two maps shown in Figures 1.3 and 1.4. The latter is a contemporary political map of the region, showing the independent nation-states of South Asia (although not their contested boundaries). The former is a map of the region in 1795, showing British territories and others. As you can see, the largest identifiable presence at this time was the ‘Mahratta Confederacy’, a network of federated states that during the eighteenth century had superseded the Mughal empire as the principal political authority in large areas of central India. The change over this period of just over 200 years is demonstrably dramatic. A map of India from a period in between – say, 1860 – would again show a dramatically different picture.

Figure 1.3 South Asia in the eighteenth century. Originally published in Charles Joppen (ed.) (1907) A Historical Atlas of India for the Use of High Schools, Colleges and Private Students, London: Longmans, Green and Co.

Figure 1.4 South Asia: modern nation-states (South Asia, UN Map No. 4140 Rev. 3, January 2004). Reproduced courtesy of the United Nations.

Examining these maps in time does not, then, provide us with a story of straightforward development. Rather, they seem to emphasize disjuncture and a multiplicity of narratives. This is a principle that we want to apply more widely. The temptation is always to bring order to history by demonstrating that one thing led to another, and that historical development has occurred in a series of eras. But there are always interests involved in such ordering. Most notoriously in South Asia, history has been seen as divided into Hindu, Muslim and British eras. This simplification springs originally from a nineteenth-century history of the region by the Scottish intellectual James Mill (1817). We can immediately see the political interest behind such a systematization, legitimizing the British era as ‘rational’ government by comparison with its predecessors. Our approach in this section aims to disrupt such narratives of development by presenting a series of snapshots from South Asian history. Each provides a different view, or narrative map, of this history. Continuities may or may not be apparent, but the snapshot form helps emphasize the need to be alert to the narrative processes that make such links. We also remind the reader that the snapshots themselves remain ‘interested’. Just like Mill, we do have an agenda. Because of the subject of the book, each of our historical snapshots is linked with particular portrayals of religion in modern South Asia. As you engage with them, you should remain alert to this interest, and ask questions about what sort of history is missing.

Snapshot One

Located in the northwest of our region, modern Pakistan, cities flourished from roughly 2600 BCE to form the Indus Valley civilization, one of the world’s oldest civilizations.5 Traces of the cities of Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa only started to be excavated in the 1920s. The evidence demonstrates that the Indus cities were established on an orderly grid pattern with effective water and sewage works, brick buildings and a range of public spaces and roads. There is also evidence of trade across central and western Asia, and of the production of finely worked artefacts in gold, copper and lead. In terms of evidence of religious practice, seals showing a horned god, and figures with large breasts have been found. These have been linked both with claims for the unbroken continuity of Vedic Hinduism from this period, and with opposing claims that indigenous south Indian Dravidian religion (supposedly evidenced in the goddesses) is older than north Indian Vedic forms. The reality seems both more complex and more elusive, and is likely to remain so until the script used by these people can be deciphered.

Snapshot Two

The Indus Valley civilization, the reasons for whose decline are still unclear,6 was superseded in the northwest by the so-called Vedic civilization.7 The theory that Vedic civilization spread as a result of invasion has now been refuted (see Chapter 3). The relation between the two civilizations has, however, been a subject of much (politically loaded) dispute, and remains important in understandings of religion in modern South Asia (for a range of views see Bryant and Patton 2005). On current knowledge, it seems likely that Vedic civilization emerged slowly through interactions and cultural fusions between some of the different peoples present and proximate to the remains of the Indus Valley culture after 1700 BCE. Largely nomadic rather than city dwelling, these pastoral people moved across the plains of northwest India, later moving down to graze cattle along the Gangetic plain, before settling to form a range of kingdoms (mahajanapadas) that dominated the northern part of the Indian subcontinent during the course of the first millennium BCE. Our knowledge of these people and their religious practices comes largely from the Vedic texts; unlike the Indus Valley, nothing in the way of objects and buildings has survived from this later period.

The orally transmitted Vedic texts (which have become seen as the sacred texts of Hinduism; see Chapter 3) give us a rather partial view of the structure of Vedic society through the eyes of its male brahmin transmitters. In particular, they introduce the idea of varna (ideal social group or class) and its relation to cosmic and ritual order (see Chapter 7A). The texts also portray links between the individual and the cosmos itself, links that can be manipulated in ritual chants or meditations. This key theme reappears in later Hindu epic and devotional traditions when these come under brahmin control (see Chapter 4). It also surfaces in Tantric traditions (Chapter 6) in different ways.

Snapshot Three

In the latter half of the first millennium BCE, we may detect emerging forms of resistance to a ‘Vedic view’ of the world. Vardhamana Mahavira and Siddhartha Gautama are cast as agents of change in this respect.8 The stories of their lives say they came from royal backgrounds in the mahajanapadas of northeast India, defied the conventions of their period by renouncing their position in the world and spoke out against the structures of society and cosmos established in Vedic texts. The anti-Vedic teachings of these two figures are better known today as Jainism and Buddhism. However, it is important to put this understanding in context. To present this just in terms of ‘Vedic’ and ‘anti-Vedic’9 worldviews oversimplifies. These were just two of many varying views of the world that were developing over this period, influenced by complex social, economic and political changes (Olivelle 1995). Both teachings did, however, emerge to gain varying degrees of influence over social relations and political structures. In particular, they were influential in the development of the enormous Mauryan empire, which grew during the late fourth century and by the mid-third century covered much of the subcontinent. Most famously, Siddhartha Gautama’s teaching was promoted vigorously by the Emperor Ashoka (reigned 269–232 BCE), who has become an icon of just rule. His symbol, the chakra (the wheel of dharma, or order/justice), features on the flag of the modern nation-state of India.

The Tamil country in the far south of the subcontinent around the first to fourth centuries CE was known as the country of the three kingdoms. It supported trade from the interior, along the coast, with southeast Asia and Rome, and sustained a thriving culture expressed in Tamil love and war poems, and in plays. These literary sources bear witness to the diversity of religious practices current at the time. In Maturai (Madurai), already the capital of the Pandiyan kings, temples to the deities Shiva, Vishnu, Murugan, Balarama and the goddess Pattini flourished, as did Jain temples. A Buddhist nunnery was an option for a woman who wished to renounce. Women became spokespeople for deities, ascetics of various kinds wandered, tribal hunters performed ceremonies, brahmins chanted the four Vedas; other brahmins turned from Vedic ritual and sang, perhaps to different deities, ornamented and worshipped with flowers. As Buddhists flourished with the growth of rice agriculture in the coming centuries, and Jains expanded and gained patronage through maritime trade, some brahmins sought to gain influence over devotional (bhakti) movements, drawing their poetic inspiration from early high-culture poems as a way to reassert and extend their power (see Chapters 4 and 5). As this suggests, devotional cults became engaged with the structures of established authority (kingly as well as brahminical).10

Snapshot Five

After the decline of the Mauryan empire in the second century BCE, different regions of South Asia were ruled by successions of kingdoms, including the short-lived Greco-Bactrian in the northwest. Key dynasties included the Gupta dynasty, a major power linked with brahminical strengthening in central and eastern India around the fourth to sixth centuries CE, and the Chola dynasty, another long-established power in southern India (mentioned in inscriptions from the Mauryan period), one of the ‘three kingdoms’. By the ninth century CE, this had expanded throughout the south and extended its influence up the eastern coast of the subcontinent into Bengal, as well as further south into Sri Lanka. This snapshot shows South Asia as a region of dynamic economic growth, trade links developing with many other parts of the world. The Indian Ocean trade had a significant impact on western India in particular, with different groups, including Christians, settling in coastal regions such as Kerala, establishing the kind of cosmopolitan culture we saw in Mattancheri. Part of this cosmopolitanism was generated by long-established trading links with Arab communities from across the Indian Ocean. These links provided the primary route for the spread of Islamic culture in southern and central India from as early as the eighth century.

The northwest was also the site of emerging Islamic influence, both through a range of invading forces and through economic and religious integration associated with Sufi Muslim shrines. In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, a range of Turk and Pathan armies pushed down through Punjab into northern India, establishing the Delhi Sultanate, a succession of unrelated dynasties that ruled over a fluctuating area of north and central India. Like contesting powers in other parts of the subcontinent, they used force and violence where necessary to establish their own superiority. Stories of these interactions, however, show huge variation in their attitude to and presentation of these encounters and subsequent social relations.11

The Delhi Sultanate was superseded by the Mughal dynasty, a major force that established paramountcy in much of the subcontinent from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century. Islam, although ever present in the culture and politics of the court, was by no means the defining factor in the governance of the empire. Largely, the Mughals ruled by the so-called ‘segmentary system’, whereby imperial authority was focused on the towns and cities of the Gangetic plain, Punjab and Bengal, whilst other areas were governed by client kingdoms of a range of different types. Many people in India became Muslims during this period, but for the most part their new practices were assumed through the influence of Sufi pirs and shaykhs (Eaton 2000), holy men who operated within the fabric of South Asian society, and whose influence we will refer to throughout this book.

Snapshot Seven

Regional rulers remained a significant factor in the administration of South Asia throughout the Mughal period. As the empire began to decline in the mid-eighteenth century, some of these regional administrations assumed a greater degree of power. Amongst these were the Mahratta Confederacy, established by Shivaji Bhosle in the late seventeenth century, the Hyderabadi kingdom ruled over by the Nizams, and the East India Company, a British trading company established by Royal Charter of Elizabeth I of England in 1600. The Company gradually expanded its influence in South Asia, in the first instance through coastal trading posts at Surat, Madras and Calcutta. Of course, the British were not the only European power interested in the trade possibilities opened up in South Asia (we noted both Portuguese and Dutch influence in Mattancheri), but by a combination of political alliance and military conquest they expanded their influence, winning political control of Bengal and Bihar after the Battle of Plassey in 1757. From here, the Company expanded its influence dramatically across the subcontinent. By 1857, it had direct control over much of the region. The great rebellion of that year, however, demonstrated the limitations of this commercial company’s ability to administer these vast territories, and in 1858 the Company was effectively nationalized, with the British Crown assuming administrative control. Hence began the period known as the British Raj, which ended in 1947 with the partition of the subcontinent into the independent nation-states of India and Pakistan.

The period of Company and direct Crown rule is one to which we will refer consistently during the course of this book, as it is a period that had a great deal of influence on the development of modern religious traditions. This influence, however, should be viewed in perspective; it was always an influence that developed in dialogue with myriad existing traditions in South Asia. For example, it is important to remember that throughout this period British India existed side by side with a large number of what became known as Princely States. These states, such as that of the Nizam of Hyderabad (see Chapter 5), were tributary states that officially recognized the paramountcy of British power in the region. Nevertheless, they represented a longer history, which was reflected in their critical position in the negotiations towards independence in the first half of the twentieth century. Most of these states were absorbed into Pakistan and India in 1947, but one in particular has retained a major, explosive influence over the geo-politics of the region: Kashmir.

Snapshot Eight

The political problems in modern Kashmir are frequently presented as arising from friction between Hindus and Muslims in South Asia, the same friction that apparently led to partition in 1947. Although these identities are undoubtedly significant, it is important to take note of the complexities of political association and cultural development in this area. The Princely State of Kashmir was in fact formed only in the early nineteenth century, as a result of political negotiations resulting from the Anglo-Sikh Wars. The area covered is one of great diversity, with Hindu, Muslim and Buddhist traditions all being well established. More than this, the area is marked by influences of Sufi traditions and a Tantric form of the worship of Shiva, which take distinct Kashmiri forms. Such interactions show that the stark divisions between Hindu and Muslim invoked in the Kashmiri conflict emerge more through very modern social and political processes than through any ancient enmity.

In this way, our snapshot of Kashmir represents a broader point: notions of traditional enmity between monolithic religious identities need to be treated with caution, as even their projections of tradition are likely to have been fashioned in the context of modernity. Having said this, at the same time we should be wary of presenting the pre-modern period as a panacea of religious tolerance. Such a view would in itself be something of an a-historical representation, as the forms of religious identity that we associate with the idea of religious tolerance are, we argue, as much a part of our modern idea of religion as are those associated with religious antagonism.

However such faultlines have developed, it is undeniable that the partition which created India and Pakistan in 1947 was a defining moment in the history of modern South Asia. Millions of people were killed during this period. Many more millions were displaced. The antagonisms that have led to three outright wars and one proxy war between India and Pakistan since this date cannot be divorced from this history, recently described as ‘a nightmare from which the subcontinent has never fully recovered’ (Bose and Jalal 2004: 164). Bangladesh was also fashioned in this crucible, emerging out of the 1970 war as an independent nation-state, no longer tied to Pakistan under the pretext of religious commonality. (On the process, experience and ramifications of partition, see Hasan 1993; Khan 2007; Butalia 1998; Pandey 2001; a good summary is provided in Bose and Jalal 2004: chs 16 and 17.)

Snapshot Ten

A final contemporary snapshot of the region has to take account of these threads of history, and also acknowledge again the diversity that we have emphasized throughout. The formal forms of government in the region, for example, range from secular republics (India, Nepal), through republics defined by religion in various ways (Pakistan, Bangladesh, Maldives, Sri Lanka), to religiously defined monarchy (Bhutan). As this suggests, democracy has been the dominant political principle in the region during the postcolonial period, although all the republics have had periods when democratic rule has been compromised in one way or another, and Nepal has only recently turned to this system, having been a monarchy before 2008.

Some of the most dramatic changes in the region in recent years can be attributed to various effects of globalization. In the 1990s, the Indian economy was radically opened up to world markets through a process known as liberalization, having previously been dominated by a form of protectionist state control under the aegis of the Congress Party.12 The Indian economy has grown rapidly since this time, with multiple ramifications in Indian society. The Indian middle class has expanded enormously, now numbering hundreds of millions.13 Some groups have undoubtedly been left behind, creating sharp divisions in social relations, a scenario graphically described in the recent novel The White Tiger by Aravind Adiga (2008). India’s urban environments have changed rapidly, with discourses of consumerism and some strident forms of nationalist and religious identity becoming prominent features.

Another major impact of globalization has been the involvement of the region in the politics of militancy and counter-militancy associated with Islam. Since the attacks on the USA in 2001, Pakistan in particular has become a major launch pad for the propagation of what has become known as the ‘war on terror’ in Afghanistan. The growth of US influence in Pakistan has had its ramifications, with a strain of militant Islamic resistance flourishing on the basis of institutions and ideologies previously promoted during the 1980s, partly by the Islamizing Pakistani military dictator Zia ul-Haq, and partly, ironically, by the same US influence which was at that time geared towards combating the Russian invasion of Afghanistan. Militancy in the twenty-first century has had its effects over the whole region, with the Indian nation-state in particular demonstrating a sensitivity to the threat, and a tendency to relate it to its post-Independence antagonism towards Pakistan.

These snapshots of history and landscapes of diversity have provided us with some glimpses of our region. We hope they have indicated that the constantly adapting practices and ideas of South Asia’s religious traditions are deeply embedded in the politics, social and economic relations, and cultural discourses of South Asian life. In the next section we turn to situating the concept of ‘religion’ more explicitly, and show how we intend to use that concept in relation to the ‘religious traditions’ of our title.

Situating Religion: The Growth of a Concept

We began this book by noting the common assertion that South Asia is an area of the world that is marked by the presence of many different religious traditions. It is often presented as the ‘home’ of Hinduism, Sikhism, Jainism and Buddhism, and the ‘host’ to other religions – Zoroastrianism, Judaism, Bahai, Christianity and especially, of course, Islam. Indeed, this is a model used by one recent introduction to the religions of South Asia (Mittal and Thursby 2006). Using this model, we could say that different elements of our landscapes of diversity represent the presence of these different religions: that, for example, the different institutions we have referred to in Mattancheri represent the presence of Judaism, Hinduism, Christianity, Islam and Jainism in this small area. Although we see value in acknowledging this range of traditions, we want at the same time to signal a sense of caution about seeing the diversity apparent in a place like Mattancheri as the proximate presence of five different religions, two of them indigenous and three of them imported. Our caution relates to what we see as the sense of organizational coherence and organic growth implied in such a picture, attributes that need to be critically examined in the light of other evidence from our landscapes, which might challenge this picture.

But what do we mean by ‘organizational coherence’ and ‘organic growth’? By the first we refer to the sense that different religions each have a kind of systematic, internal logic that entails a distinct mode of being and thinking. So:

Such statements almost suggest that religions have their own personalities, and that adherence to them will ‘naturally’ lead one to act and think in coherent and predictable ways. ‘Organic growth’ invokes along with this the idea of singular development. So:

Here, we get a sense of Sikhism and Christianity developing at slower or faster rates from ‘birth’ or ‘importation’ but always, as it were, following parallel paths towards their contemporary status. Both ideas imply that these religions have a distinct, objective existence of their own, and that together they make up ‘the religions of South Asia’.

This book seeks to challenge this view of South Asian religious traditions as a normative view. That final phrase is important, as it signals that we are not trying to deny that this view has value; rather, we are trying to de-centre it, to encourage you to see it not as the only or ‘natural’ way to think about religion in South Asia, but rather as one of several valuable models for understanding the many practices that make up these landscapes of diversity.

Our reasons for doing this are several. First, as we intimated above, we are concerned that such a model does not adequately encompass the range of practices, ideas and objects operating in these landscapes. The residents of Dadyal, for example, seem to defy expectations, with practices that ride roughshod over the idea of religions as coherent, discrete entities. Various authors have commented on this apparent incongruity. For example, in the introduction to his book The Construction of Religious Boundaries (discussed in Chapter 9), Harjot Oberoi describes the process of researching religion in nineteenth-century Punjab, commenting:

I was constantly struck by the brittleness of our textbook classifications. There simply wasn’t any one-to-one correspondence between the categories that were supposed to govern social and religious behaviour on the one hand, and the way people actually experienced their everyday lives on the other.

(Oberoi 1994: 1–2)

For Oberoi, then, there is a kind of lack of fit between these ‘textbook classifications’ and the realities of his research data.

One way to explain this is to take a step backwards and think about the idea of religion itself. You may have come across the idea that there is no equivalent word to ‘religion’ in any of the languages that are prevalent in South Asia. In particular, the classical Indian language, Sanskrit, has no such word, although the terms dharma and parampara are often adopted nowadays for this purpose.14 Languages, of course, are critical components in the construction of social reality (Hall 1997). What this might suggest, then, is that the social realities of South Asia do not ‘have’ religion, and that consequently we should not use this term when talking about South Asian ideas and practices.

In one sense this is a ludicrous statement.15 It certainly goes against the popular understanding of this region as uniquely spiritual and ‘driven by religion’. The argument against the use of religion, however, is grounded in an objection to just such exoticization. ‘Religion’ (as we understand it today) is recognized in this line of argument specifically as a category that has developed in Europe (and to a certain extent America), and been brought to other areas of the world through European expansion and colonialism. Authors such as Tim Fitzgerald (2000) and Roger Ballard (1996) identify it as a kind of instrument of oppression that has functioned since the colonial era (and especially the nineteenth century) to discipline certain elements of South Asian culture and society. Subversive practices and ideas that defy classification or threaten particular types of social order have been pushed to the margins. In addition, the economic vitality of the region has been implicitly devalued by its identification as uniquely spiritual or religious. Such ‘otherworldliness’ provided a convenient justification for colonial rule, with its promise of ‘material progress’. In an era in which the Indian economy is growing at a faster rate than that of any in the so-called First World, this seems particularly inappropriate. There is, then, a certain postcolonial logic to the rejection of the idea of religion in a South Asian context.

Various authors have, however, argued against this. Some argue that, despite its ‘brittleness’, it is a category which has to be deployed in order to construct valid comparative analyses (Fuller 1992; Sweetman 2003a). Others argue that denying religion to South Asia is little more than another Western power game, through which South Asian practices and ideas will be marginalized further as ‘folk practices’, not ‘proper’ religion (Viswanathan 2003). A related and interesting line of argument is that the ‘Western imposition’ model is a rather simplistic understanding of the dynamics of power relations. Complex social and political processes are erased in the invocation of ‘Western power’, ironically marginalizing oppressed people yet again by denying them any agency in the construction of their own social realities (Lorenzen 2005). In addition, there is a further danger that the Western imposition argument places too much emphasis on the changes of the nineteenth century. As we will demonstrate in this book, the traditions we are dealing with have long and intricate histories, informed by complex political and social relations developed over centuries, and the intervention of charismatic figures, movements of resistance and philosophical insights into the nature of the world in which we live. All these aspects should be acknowledged as critical factors in the development of modern South Asian religious traditions.

At the same time, there is a persuasive argument to suggest that the modern period has had a major influence on the way in which these traditions have come to be organized and understood. We acknowledge that the idea of ‘the modern period’ is contestable, just like the category of modernity itself. Nevertheless, the last 300 years or so have seen a period of rapid and dramatic change in the world. Enormous social mobility and conceptual exchange have been fuelled by economic integration and technological advances. For our purposes, we take such processes of mobility to represent the onset of modernity (a similar argument is made in Appadurai 1996: 28), and it seems undeniable that the concept of religion, as a facet of human practice and experience, has developed through them. Roughly from the Enlightenment (early and mid-eighteenth century), ideas about how to understand the concept of religion and its place in social and political life were transformed in many parts of Europe and North America. The emergence of self-consciously non-religious approaches towards science and reason was accompanied by the development of newly powerful social groups and opportunities for political association. Religion came to be considered beside science and reason, simply one aspect of social existence, rather than interwoven throughout (Asad 1993). This transition is sometimes known as ‘objectification’ – understanding religion as self-contained, having an objective reality, identifiable as religion.16

Geo-political expansion was also a feature of the transformation of these societies. European powers increasingly fought over and acquired control of territories across the globe. In this context, an objectivized Christianity-asreligion was brought into contact with other ‘religions’, perceived as similarly self-contained, objective realities. Increasingly, the notion of World Religions emerged through such processes.17 Perhaps the clearest example of this is the modern idea of ‘Hinduism’. Many scholars have noted the introduction of this specific term in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries (see, for example, Oddie 2006), in missionary and other traveller accounts. The term derives from the older term ‘Hindoo’. There is much debate between scholars as to whether (and when) this term itself had a religious meaning, or was used primarily to signify geographically located people (for a good account of these debates, see Pennington 2005). The suffix ‘-ism’, however, is undeniably new in this period, and indicates the kind of shift in thinking about ‘religion’ to which we are referring. Hinduism is characterized at least paradigmatically as a ‘system’, comparable to others apparent in the South Asian landscape. A similar ‘constructivist’ history has also been told about Jainism (Flügel 2005) and Sikhism (Oberoi 1994). In the context of global historical developments, these categories began to emerge as discrete social realities, major or minor instances of the general phenomenon known as ‘World Religion’ or ‘the World’s Religions’.

In the book we will be referring to this idea of a ‘World Religions model’ as a significant factor in modern South Asia. But as we made clear earlier, it is not the only way of looking. By briefly historicizing its development, our intention here has been to demonstrate that this is just one intellectual history (albeit a very influential one). Others are also significant.

The problem arises, however, as to how to locate these alternative histories, without reference to the religion concept. One possibility is to deploy apparently indigenous categories. This has been the approach taken by the anthropologist Roger Ballard (1996), who has developed a four-dimensional approach to Punjabi religion based on the key concepts of panth, kismet, dharm and qaum.18 These refer to commitment to a spiritual teacher (panth); ideas or practices designed to deal with adversity and the unexpected (kismet); divine norms variously understood, to which all should conform (dharm); and forms of community identity (qaum). Ballard’s argument is that one can identify these different dimensions operating in Punjabi religious practice in a way that frequently contradicts the logics of the World Religions model. A person who might qaumically identify as a Hindu, for example, might have values (dharm) related to honour that are shared with his Sikh neighbour, and might turn for panthic and kismetic inspiration to the shrine of a Muslim pir, as we saw in Dadyal.

It is important to realize that what Ballard is suggesting is not a model of syncretism. Syncretism implies a merging or combination of elements of existing discrete traditions (an approach that, ironically, seems to reinforce the World Religions model).19 Rather, he suggests that these dimensions enable a different way of understanding the organization of everyday religious practice, which has not been governed by, or organized on, the basis of religion as such. There are some problems with this somewhat schematic model (see Suthren Hirst and Zavos 2005), but it does help us to see that there are other ways of looking that can make sense of, and help us to understand more fully, the way religious traditions play out in South Asia.

Looking at Religious Traditions

We wish to take a lead from this general observation, and move from it to explore not so much an alternative way of looking at religion, but rather a whole range of ways of looking at religious traditions that may be deployed selectively and critically as a means of developing a multi-perspectival approach to our field. In presenting this approach, we aim to provide not only ways of looking that may be more appropriate to different ideas and practices, but also a range of ways of looking at the same sets of ideas and practices. This multiple approach is based on our understanding that the world of social actors (i.e. people) is always constituted through layers of discourse – what the anthropologist Peter Gottschalk (2000: 3–4) describes as ‘temporal, spatial and social maps’ through which people make sense of and understand the world around them.

To establish a sense of this multiplicity, our approach is heavily engaged with context, or rather with investigating the many different factors that effectively operate within and constitute those networks of contexts critical to the social construction of knowledge. The emphasis of this book is on placing religious phenomena within these networks. Responding to this dynamic social reality, we differentiate the terms ‘religion’, ‘religions’ and ‘religious traditions’ as follows. We use ‘religion’ to refer to that modern category whose development we have outlined above, and which different ‘religions’ – Christianity, Hinduism, Islam and so on – are held to exemplify. These terms will enter consistently into our analysis, deployed as one of the ways we address our subject matter. At the same time, we employ the term ‘religious traditions’ to denote something different. We use it in a pragmatic attempt to represent the panoply of ideas, practices and objects that today are commonly recognized as belonging to a religion, but which we wish to signify could be understood through a range of different ways of looking. These traditions may have old roots, but they may also be recently invented (Hobsbawm 1992). We are, then, emphatically not proposing ‘religious traditions’ as a pre-modern alternative to the modernity of ‘religion’. Our intention is rather to demonstrate how continuities have come to form a significant feature of modern social formations, often alongside and indeed woven into, and becoming, modern articulations of religious identity. In pursuing this approach, we apply different ways of ‘cutting across the available data’, to use Will Sweetman’s (2003a: 50) phrase. These include looking at teacher traditions as key social formations in South Asia, but ‘religious traditions’ are not to be reduced to this formal notion of parampara (teacher–pupil succession). Rather, the term indicates our open, multi-layered approach, based on different ways of looking. Distinguishing this from the idea of religion as one particular way of looking is critical, and we ask you, as our reader, to hold this distinction with us, to commit at least temporarily to our construction of reality, as you would if you were attending a play.

The Shape of the Book

In what we might then imagine as the prologue to this play, you may have noted a range of metaphors associated with looking. Snapshots, maps, glimpses have all helped us to explain our approach to our field. But there is a loaded history in such metaphors. In particular, the look or ‘gaze’ of colonialism has been implicated in the construction of colonized societies as exotic, other, ripe for political domination (Mitchell 1988, and also Chapter 8). Under such circumstances our use of such metaphors to explore religious traditions in a region of postcolonial nation-states may be considered rather risky. Our objective, however, is to subvert the power of dominant ways of looking by producing, as it were, new perspectives on the gaze. So our interest is always on many ways of looking, rather than on the acceptance of a single, authoritative view. As Gottschalk (2000: 4) says, ‘If we find that only one map is enough, then we should suspect ourselves of oversimplification.’ What we need instead is ‘a set of maps that we shuffle occasionally according to the questions we ask’.

In this connection, we introduce one further metaphor that we will deploy throughout this book. It is suggested on the front cover. This is the metaphor of the kaleidoscope. We are indebted to the scholar Diana Eck, from whom we have drawn this idea. As you will see in Chapter 2, she has used it to describe the relative position of deities in Hindu traditions (Eck 1998: 26). We would like to move outwards from this to deploy the metaphor as a critical method of looking. Twisting the kaleidoscope delivers ‘a constantly changing pattern of … reflections as the observer looks into the tube and rotates it’ (SOED 1993: 1470). This twist of the kaleidoscope will be our way of referring to that multi-perspectival approach towards our subject matter described above, enabling, we hope, a range of such reflections, or understandings, to emerge. As with the kaleidoscope, so with these twists: the same data will be viewed in different ways, each a construction itself, yet allowing us to develop a more nuanced view of our subject than a single perspective could give.20

The book is divided into two parts. The chapters in Part I are structured around some fairly standard concepts associated with the study of religion. We begin with the idea of the divine in Chapter 2, before moving to explore texts, myths and ritual in the following chapters, and then turn to two issues that apparently relate more particularly to the religious traditions of South Asia, the teacher–pupil relationship and the concept of caste. With each of these chapters, however, our approach will move outwards from this initial identification of a core concept to disrupt notions of how it should be approached. In particular, we want to disrupt the idea that the specificity of these concepts in a South Asian context is always best interpreted through the World Religions model. We will then explore continuities that appear to cross the boundaries between different religions in relation to notions of ritual practice. We will also problematize the idea that each religion is tied to one particular way of approaching these key concepts. Our approach to the divine, for example, explores the many ways of understanding the idea of divinity, which are apparently encompassed by that which we commonly recognize as Hinduism. These chapters inhabit landscapes of diversity; they demonstrate from modern examples, and, by drawing on the historical development of diverse traditions, how our settled notions of religious identity, Oberoi’s ‘brittle categories’, are transgressed by practices and ideas in context.

If Part I of the book is focused on disrupting these settled yet ‘brittle’ ideas of how religion is organized, Part II is focused more on understanding the ways in which the category ‘religion’ has come to be part of, and has influenced, the shaping of South Asian religious traditions. Our focus here is initially the nineteenth century, when the radical encounter between different knowledge systems influenced ways of looking at and representing religious identities in profound ways. In Chapters 7–9, we will explore in particular the emergence of modern ideas about what constitutes Hinduism, Islam, Sikhism as South Asian religions. This is not necessarily to say that definite notions of religious identity were not apparent in the region before the nineteenth century. Rather, our argument is that it is not possible to understand the ways in which religion operates in contemporary South Asia without taking account of the complex historical processes that marked this period. In Chapters 10 and 11, we move from this focus to consider some further key factors in the broader modern period that have impacted on ways in which religions are understood and acted upon. In particular, notions of public and private space, and political activism at a variety of levels, have been very influential in the articulation of modern religious identities. In Chapter 11, we also return to the idea of different ways of looking, to show how the contrasting approaches in Parts I and II help develop a critical, multi-layered understanding of religious practices and ideas in modern South Asia.

As well as the contrast between the two parts of the book, we hope you will also see continuities. In particular, there is a continuity in the structure of each chapter. Each begins by focusing on a case study, a particular event or text intended to provoke questions to deepen understanding. We hope to encourage a questioning approach throughout the book. From questions raised, we work outwards from the case study to explore how different contexts provide us with new ways of looking and understanding, to develop answers to questions raised. This strategy is deployed in both parts, as our approach stresses the constant need to ground the phenomena studied in a range of interconnected contexts.

Sometimes these contexts are straightforwardly historical. It is necessary, for example, to understand something of the historical background of particular figures such as Anandamayi Ma and Rammohun Roy in order to understand the texts associated with them in Chapters 5 and 2. In addition, however, these contexts may be more discursive or theoretical. In Chapter 8, for example, we explore the issue of Orientalism and postcolonial theory as one context for understanding the work of Sayyid Ahmad Khan and others. This is because events and texts are always affected by a range of broader ideas, as well as more immediate elements of cultural, social, economic and political life. As Kim Knott (2005: 119) explains, religion operates as ‘a dynamic and engaged part of a complex social environment or habitat, which is itself criss-crossed with wider communications and power relations’.

In each chapter in Part I of the book, this concern will be reflected not just in an examination of a range of broader contexts to the case study, but also by three consistent ‘twists of the kaleidoscope’, helpful for exploring the wider power relations associated with each chapter’s conceptual theme. These three twists will focus respectively on issues of gender, politics and religion, in relation to the examples used in the chapter. The final one of these twists, religion, is similarly deployed in Part II of the book, where the focus is more clearly on the specific significance of this idea in shaping the modern realities of South Asian religious traditions. We hope that these continuities will enable you to make interesting connections across the material available in this book. Questions, tasks and suggested further reading are there to help you develop your own research beyond it.

Encouraging further research is an important objective for us. As we have emphasized, our treatment of the region, and religion within it, is not and cannot be comprehensive. At a pragmatic level, our main focus is on – even then necessarily limited – examples from the Indian subcontinent and the modern nation-states of Pakistan, India and Bangladesh. For Bhutan, the Maldives, Nepal and Sri Lanka, other sources will provide perspectives on their history and religious traditions, doing them more justice than we can here.21 Carrying out research will enable you to follow up your own particular interests. At a methodological level, you will already realize that we are intent on encouraging you to develop a critical approach to the conceptual categories through which understandings of South Asian ‘religion’ have been constructed. There are no fixed boundaries to these traditions (as with the region itself) – they are negotiated, developed, contested in a range of historically grounded contexts, and so necessarily resist any idea of total coverage. Our hope, rather, is that the range of examples and different ways of looking explored in the following chapters will help you to develop your own critical and nuanced approach, both to the examples of the landscapes of diversity explored within, and to the far wider landscapes you will discover beyond.

* The language diversity of the South Asian region is immense. There are no fewer than eighteen official state languages in India, in addition to the national official languages, Hindi and English. Overall there are twenty-nine languages in the country with over a million speakers. Over the rest of the region, the main languages are Bengali (the main language spoken in Bangladesh), Punjabi, Pashto, Sindhi, Seraiki, Urdu and Balochi (each with more than 6 million speakers at the very least), and Sinhala and Tamil (the main languages in Sri Lanka). Nepali is spoken by about 40 per cent of the population of Nepal, but there are recognized to be about 120 different languages spoken in this country. The three main languages spoken in Bhutan are Dzongkha, Tshangla and Nepali, and the main language in the Maldives is Dhivehi, although English is increasingly the language of commerce and education there.