15 ~ The middle years: second marriage

1

Four years after Edison had perfected his carbon filament lamp there were only twelve city stations, on the model of Pearl Street, in operation; in all America only 150,000 of his lamps were in use. Much more rapid progress had been made in selling isolated lighting plants for factories, stores and hotels; by January, 1884, these numbered about two hundred, and used from a few dozen to three hundred lamps each. But all of it amounted to almost nothing compared with the huge gaslight industry which he had sworn to supplant. After the original Pearl Street station reached its full load limit, no more generators were added for several years; no annex was built until 1886, and added business was simply turned away.

The trouble was obviously due to the extreme conservatism of his financial backers. But how could he expand the business when others controlled its policy?

Try as he would, Edison could not stir things up without the approval of the holding company which owned his lighting patents. At the formation of the Edison Electric Light Company in 1878 he had been the largest stockholder, owning 2,500 of the original 3,000 shares. But two years later, when the project promised to be successful, the capital of the company was increased about threefold; the Morgan partners and Western Union directors subscribed to the bulk of the new capital issue, while Edison was forced to sell part of his original holdings to finance the lamp and generator factories. Thus, as soon as the business showed promise — even Pearl Street was earning a modest profit by 1884 — he had lost control of the patent-holding company, which was the key controlling the whole enterprise.

“The importance of Morgan support to Edison’s electric lighting project can hardly be overemphasized,” remarks a historian of the electrical industry in America.456 Edison himself had told people he expected great benefits from this connection. The biographers of Pierpont Morgan (especially his son-in-law, Herbert Satterlee) have described him as enthusiastic for the electric light, and “intensely progressive.”457 He ordered one of the first isolated plants for his own home. Economists and social historians have cited Morgan’s interest in and support of Edison’s invention as an example of the innovative spirit that ruled in high capitalist circles after the Civil War.

Certainly the forehanded Morgan was interested in the potentialities of the Edison system from the beginning; it appealed to his imagination. One of his partners — at first Fabbri, and after his early death, C. H. Coster — regularly acted as treasurer of the Edison parent company and of its subsidiary, Edison Illuminating. If there was anything in this new project Morgan was going to keep his hand over it.

The situation cried out for an expansive strategy. But the banking group stolidly opposed Edison’s enthusiasm and insisted that he “go slow.” His three-wire invention of 1883, for example, offered great economies of distribution and, as he pointed out, made it possible to introduce lighting systems profitably even in small country towns where houses were far apart. But the directors firmly refused to finance such projects, and the inventor was forced to draw on his own capital to carry out the historic three-wire installation at Sunbury, Pennsylvania.

After Morgan had installed the Edison lighting plant in his redecorated house on Madison Avenue, in the autumn of 1883, he held a big reception for four hundred guests. One of them, Darius Ogden Mills, the famous gold mine operator and stock market plunger, was so impressed with all those brilliant new lights that on the following morning he walked into the office of Drexel, Morgan & Company and ordered the purchase of a thousand Edison shares. “Pierpont heard of this at once,” and before Mills could go out the door, caught him and asked him what he knew about the Edison light.

“I know all about it,” answered Mills.

“All right, we will take your order,” said Pierpont, “and any other orders of the same kind, but I am going to put a condition on my partners with respect to such orders... that for every share of Edison stock they buy for you they buy one for me.”458

This incident has been cited as showing Morgan’s enthusiasm for the Edison venture. What it suggests rather is that Morgan was serving notice that he would allow no one else to take control over this promising industry; and he was a most determined and formidable man. By the end of 1883, the meetings of the directors of the Edison Electric Light and of its two non-manufacturing subsidiaries, the Edison Illuminating of New York and Isolated Lighting, were regularly held in Morgan’s office.

Major Sherburne B. Eaton, a prominent member of the New York bar who in 1882 succeeded Dr. Norvin Green of Western Union as president of Edison Electric Light, reflected the Morgan policies when he admitted frankly that the banking group was “loath to make use of money to push the enterprise.”459

The new electrical industry intrigued Morgan; but he saw that it was as yet pretty small for him, and earned limited returns for the large capital it used. While refusing Edison some modest credits of a few thousand dollars, Morgan was raising millions to finance big railroad combinations like the New York Central and the Great Northern, which then yielded assured profits.

Of Edison’s financial patrons only Henry Villard seemed to “believe in the light,” as he said, with all his heart. Villard might have lent Edison powerful support at this stage of affairs, for he entertained grandiose ideas about the future Electrical Age. But in January, 1884, the newly arrived railroad king had a great fall; he had overextended things in expanding the Northern Pacific, exhausting its treasury, so that the big railway system was thrown into receivership. This affair caused a fair-sized panic in Wall Street and created much feeling against Mr. Villard, who was attacked in the press on the score of alleged mismanagement. Morgan, it was said, had always mistrusted Villard.460 At all events he was hors de combat — so far as being able to help Edison in his fight — at least until he could accumulate another war chest.

A few years earlier the railroad promoter had contributed $40,000 to Edison’s experiments with the electric locomotive. In Villard’s hour of need, the inventor had returned this sum; he recalled later:

When Mr. Villard was all broken down and in a stupor caused by his disasters in connection with the Northern Pacific, Mrs. Villard called for me to come and cheer him up. It was very difficult to rouse him from his despair and apathy, but I talked about the electric light to him, and its development, and told him that it would help him win it all back and put him in his former position.461

That was exactly what Villard did, after a while, in trying a “comeback.” He retreated to Europe, resumed his former connections with German banking interests, and persuaded them to invest large sums, under his direction, in the growing Edison companies in America, which brought in very handsome profits.

Edison’s impressions of Villard, not only on that unhappy occasion in 1884, but also in later, more fortunate, years, was that he was humorless like Jay Gould. “He was a very aggressive man with big ideas, but I could never quite understand him.” When Edison, with all his powers of invention, told his choicest stories, Villard “could not see a single point and scarcely laughed at all.”

Many of the big money men of that time impressed other observers besides Edison as cold fish, who knew only the icy pleasures of the market place in which they perpetually swam. Was the acquisitive instinct, then, incompatible with a sense of humor? By contrast, a creative being like Edison seems to us full of the joy of life.

At all events, he was forced to give battle alone against the financial conservatives. He tried prodding them, though it helped little. From Florida, during the winter, he would dash off letters that crackled with impatience.

What is Eaton doing about putting agents all over the country to get the towns started? How about Louisville, Auburn, Haverstraw, Hudson & other towns? Any prospects?462

According to financial gossip in the newspapers there were now two parties in the Edison organization —

one slow and conservative, the other, including the inventor, energetic and willing to spend money for the sake of making money... The result has been, as Mr. Edison himself put it, that his light has not been used on anything like the scale he might reasonably expect.463

In his view, it would be good business to set up local power stations in many small towns, show that they could be operated profitably, and then induce local capitalists to take them over. But it would need much capital to initiate such a spreading movement; and this the majority of Edison Company directors refused, holding that the local capitalists ought to raise funds themselves, in the first place, and pay for lighting plant equipment in cash, within thirty days.

At length Edison grew thoroughly fed up with the directors of his company, and especially with President Eaton, who seemed much more suited to the law than to industry. Samuel Insull described him as a pompous little man of military bearing, who strutted about his office at 65 Fifth Avenue, “holding forth like a great mogul” — but bringing in no business. Edison, however, had his champions on the Board of Directors, especially Edward Johnson, who protested at the inroads being made in their business by competitors who were infringing upon the company’s incandescent lighting patents, and urged that vigorous legal action should be instituted against them. But the attitude of Eaton and Grosvenor Lowrey, who had lately joined the conservative group, was to avoid such action for the present, in accordance with the policy announced in the Directors’ annual report of 1883:

The Edison patents, as a matter of law, not only endow our Company with a monopoly of incandescent lighting, but aside from the patents, our business has obtained such a start, one so far in advance of all competitors... that the business ascendancy is of itself sufficient to give us a practical monopoly. The one or two... competitors have thus far failed to make it worth while for our Company, in the opinion of your Board... to go to the expense of bringing suits for infringement... Our Company, from the enormous start and business advantage it has already acquired, will be able not only easily to keep at the head but also to maintain a practical business monopoly... However we still have our patents in reserve, and are free to bring suit upon them at any time that the Company may think best.464

It must be remarked that Edison himself had a horror of being involved in lawsuits over patent rights, as a result of unpleasant experiences on the witness stand in earlier suits over telegraph inventions. Sawyer and Maxim had begun to infringe on his lamp patents two years earlier. There had also been a potential contest with Swan, in England, in 1880. But Edison had written then:

My views are strongly in favor of not sueing [sic] either Swan or Maxim. My reasons are the same as advanced over a year and a half ago, when it was urged with great persistence that the directors sue Maxim.465

He had little faith in the power of the courts to protect an inventor under the public patent laws. Such litigation usually became snarled up in a web of legal technicalities introduced by the opposing lawyers, so that the ends of justice were usually defeated. Meanwhile, an ingenious rival could easily find methods of copying an original invention by introducing insignificant variations which involved no change in principle. “A lawsuit is the suicide of time,” Edison wrote in his diary of 1885.466

It was far better to depend on improving techniques and on “trade secrets,” he maintained, than to lose time and money on lawsuits. If this position seems inconsistent with his own practice of applying for patents on the hundreds of devices or processes he invented, it must be remembered that commercial usage, no doubt, accounted for a good deal of that.

The Edison lamps, in early years, surpassed all others by a wide margin in tests conducted at various expositions of 1884 and 1885 to determine life, efficiency, and economy in number of light units per horsepower. More and more talented technicians were appearing in this field, however, and the policy of the Edison Company was perhaps too complacent. Patent infringers, though only a small cloud on the horizon in 1882-1884, would become a formidable threat a few years later.

There were other issues in dispute between Edison and his patrons. Though, in truth, he had some excellent ideas about business management, his methods were decidedly informal. For example, on his own initiative he engaged a new manager to oversee the first power station in New York, which had been running at a loss for the first year or two. Edison personally guaranteed that if the man brought the business at Pearl Street up to the point where it earned 5 per cent on its $600,000 capital, he would give him $10,000 out of his own pocket. “He took hold, performed the feat and I paid him the $10,000.”

But President Eaton rightly objected that such expenditures, when not authorized by the official head of the company and its treasurer, were irregular, and the directors refused to honor them. As Edison remarked, “They said they ‘were sorry’ — that is, ‘Wall Street sorry’ — and refused to pay it. This shows what a nice, genial, generous lot of people they have over in Wall Street.”467

There were also instances of Edison’s laying claims against the E.E.L. Co. for out-of-pocket expenditures made in order to insure the success of their project. In one case he had authorized certain agents to carry on lobbying activities before the New Jersey legislature in behalf of a favorable electric lighting act. Reflecting the easy political morals of the time (and other times too) Edison promised certain legislators one thousand dollars “payable after the passing of the Act.”468

But when it came to submitting clear records of such transactions to the executive officers of the company Edison usually did not have them. What Insull called “his habitual contempt for bookkeeping,” and his informal or impulsive ways of doing business forbade keeping such accounts. It needed, in fact, much patient pleading by President Eaton before Edison was persuaded that he must make no expenditures without the authority of the parent company’s officers.

A more serious issue, however, arose from a real conflict of interest within the group of Edison companies that had been so hastily thrown together. The manufacturing group were usually at loggerheads with the holding company, Edison Electric Light, which controlled the Edison patents, the New York power station, and the Isolated Lighting Company — in short, the patent-owning and utility-operating end of the business. Edison and his private partners — mainly Johnson, Batchelor, Upton and Bergmann — manufactured accessories: lamps, dynamos, motors, conducting mains, and other appliances needed for lighting plants using the Edison system. On these products royalties were usually paid to the parent company; and they were supplied under contract with the parent company.

For example, by an agreement of March 8, 1881, the Edison Lamp Company sold lamps to the parent company and its licensees for thirty-five cents each, the lamps selling at retail for one dollar each during the first few years. But as volume and production methods improved, and retail prices were reduced somewhat, this business became highly profitable for the lamp company, and the E.E.L. Co. urged that the wholesale contract price be lowered. Generally, the more profits Edison and his manufacturing partners made on lamps, dynamos, and other equipment, the more the holding and utility companies, in the view of the banking group, were disadvantaged. On the other hand, if the banking group resisted the expansion of the lighting business, the manufacturing companies were held back.

“I have always deplored the circumstances which placed you in double, and somewhat antagonistic, relations with the [Edison Electric Light] Company,” one of the directors wrote him at this period.469

In the spring of 1884, C. H. Coster, partner of Morgan, and Grosvenor Lowrey, who also wore the “Morgan collar” these days, proposed that the holding company be given “a suitable interest in, and large influence over, the manufacturing business...” It was further proposed that this be accomplished by the exchange of stock which in effect would give the holding company 40 per cent control of the Edison Machine Works, the Edison Lamp Company, and Bergmann and Company, makers of appliances, fixtures, and other “small deer.” But Edison and his chief partners, Johnson, Batchelor, and Bergmann, were unwilling to part with so much of their ownership in the going manufacturing shops which gave them a means of livelihood, in exchange for the parent company shares which as yet offered no regular income. The inventor and his laboratory assistants had launched these manufacturing firms with their own limited means, as pioneering ventures in which the banking group at first had absolutely refused to invest money. Now that the lamp company (which lost heavily the first year) and the other electrical-equipment concerns showed themselves increasingly profitable, the Morgan group were quite willing to take stock in them.

Edison was so indignant at such proposals that at one point he threatened to terminate his contract with the parent company, declaring that he had no confidence in its executive officers’ will or ability to carry out the expansion program he had in view. He also insisted that Major Eaton be supplanted as president by Edward H. Johnson.

A lively stockholders’ fight flared up during the summer of 1884. Edison and Insull spent several weeks “working like Trojans getting proxies.” Though the inventor was now a minority holder in his company, his glory was then at its zenith; a good many stockholders gave his party their proxies, one of them remarking to him that the company “seemed to have been managed with imbecility, or worse.”470

A former friend and supporter, Professor Barker, however, wrote the inventor in a tone of anxiety: “I am sorry at this collision. If you win, your capitalists are alienated, and if they win you are dissatisfied.”471

Insull worked hard for the Edison party, and he was beginning to show ambitions of his own. He seems to have regarded President Eaton as the big stumbling block. “There is no one more anxious after wealth than Sam Insull,” he wrote to a friend in reporting the battle, “but there are times when revenge is sweeter than money.”472 When the day of the annual directors’ meeting arrived, October 28, 1884, the Edison faction had won about half the stockholders’ proxies, and, as Insull announced triumphantly, everything was settled to their satisfaction. Major Eaton was to be demoted to the position of corporation counsel; and one Eugene Crowell, an elderly and inactive figure, was to succeed him as nominal president of the Edison Company, while Edison’s man, Edward H. Johnson, was to be executive vice-president. As Insull summed it up, “Drexel & Morgan have... in the face of this support which we have obtained come to the conclusion that the most graceful thing to do is to give Edison what he wants.”473

The inventor was described as having been wrought up to a high pitch of excitement and belligerency during the conflict, but felt in better humor when it was over and settled, as Henry Villard urged, “in a spirit of mutual concession.” However, a majority of the directors were now Edison’s personal adherents. At this time Edison parted company with his friend and patron Lowrey, who was dropped from the board of directors for having allied himself with the conservative faction.

Pierpont Morgan, however, continued to watch over this young enterprise. One of his partners, J. Hood Wright, became a director; and in place of Villard, who resigned (after the Northern Pacific crash), C. H. Coster also was elected to the board of directors and made treasurer. The Morgan firm continued to be banker to Edison and his companies, and remained as financially conservative as ever, especially when the inventor tried to borrow money on his anticipations — no matter how alluring — instead of sound and sufficient collateral.

In the autumn of 1884, Manhattan residents were diverted by the sight of an evening parade down Fifth Avenue, the like of which had never been seen before. Several hundred men advanced in a hollow square formation, each caparisoned in a helmet surmounted by a little glow lamp; within the square a steam engine and Edison dynamo on wheels rolled along, supplying current through a cable connected by flexible wire to each of the marchers. At the head of the column rode a gaily uniformed commander on a war charger, bearing before him a baton tipped with light. The parade signalized the arrival of Ed Johnson in power. Another of his publicity schemes was the “Edison Darky,” a dancing performer wired for light, who appeared at many expositions and fairs that season. Johnson was promoting the Edison system strenuously, and after his own circuslike fashion.

In more serious mood, on May 23, 1885, he issued a formal warning in behalf of Thomas A. Edison and his companies, that vigorous defensive measures would be taken against all infringers of Edison’s patents for incandescent lamps. Suits had lately been instituted against the United States Electric Lighting Company (manufacturing the Maxim lamp), the Consolidated Electric Light Company (having the Sawyer-Man patents), and several other manufacturers. Potential customers were now guaranteed that all who made and sold incandescent lamps not authorized by the Edison company would be prosecuted and punished to the full extent of the law.474 Hitherto no such policy had been made public, and competitors had entered the field in growing number. The first suits encountered some initial difficulties in the courts; appeals then dragged them out for almost four years longer, before the status of the contested patents was determined.

Meanwhile Johnson expanded the facilities of the Pearl Street station by adding an annex and then began building two “uptown” power stations, at Twenty-sixth Street and Thirty-ninth Street, which were completed in 1886 and 1887.

The autumn of 1885, in contrast with the preceding year of financial panic and depression, saw business humming for the Edison electrical manufacturing companies. After moving to a larger factory space at Harrison, New Jersey, the lamp company steadily reduced the number of manual operations and the labor time required. This factory was always Edison’s “baby.” With the help of Upton, its manager, and the engineer J. W. Howell, he worked out improved methods of pumping air quickly out of the vacuum bulbs and preparing carbonized bamboo filaments on a large scale. From an initial cost of $1.21 per lamp, when manufacture was started in 1880, the company lowered the production cost to about 30 cents in 1885, when it turned out as many as 139,000 lamps. Though not the first to think along these lines, Edison had very clear conceptions of mass production techniques to be contrived for this technically complex product. In the late eighties the lamp company’s output at last approached a million lamps annually, as Edison had prophesied in the beginning, and costs per unit were down to 22 cents.475

Bergmann & Company, in which the inventor held a third interest, swiftly expanded its production of fixtures, sockets, and a whole variety of light electrical goods. Edison’s old mechanic, Sigmund Bergmann, showed the commercial instinct to an unusual degree, and his concern proved to be highly profitable from the start. The bigger machine works, at Goerck Street, now employed eight hundred workers; it encountered more difficulty in its early years in producing heavy equipment and raising the larger capital needed.

The business of the Isolated Lighting Company also grew by leaps and bounds from 1885 on. Johnson sent out a whole team of salesmen, typified by the breezy Sidney Paine of Boston, who sold isolated lighting plants to nearly all the textile mills in New England. The new Edison lights going up in dreary factory towns always made a great sensation; and it was widely reported that millworkers felt more comfortable and became more efficient under their cheery glow.

Sometimes there were alarming accidents, however, as when a large hotel at Sunbury, Pennsylvania, which had just been wired for lights, suddenly began to emit huge sparks and vivid lightning flashes from all its fixtures during a storm. The insulation and wiring, tied to old gas outlets, had obviously leaked static electricity on a large scale. Edison’s representatives were often nimble-witted and ready with some explanation, true or otherwise, to calm the spirits of those who were frightened by such fireworks. To the hotel manager, who demanded the next day that the wires be ripped out, one of these agents said, “You may not realize it, but your hotel was struck by lightning yesterday. If it hadn’t been for us you’d be the proprietor this morning of... a heap of ashes. Those sparks were the lightning being shunted into the ground on our wires.”

“Well!... We’ll let the wires stay, of course,” the proprietor conceded hastily.476

By October 1, 1886, the combined Edison organization, with assets approaching 10 million dollars, amounted to a big business for those days. More than five hundred of its isolated lighting plants were in operation at various points throughout the country, using over 330,000 lamps. Central stations in large cities had risen from only twelve, in 1884, to a total of fifty-eight two years later. Similar facilities were being sold and installed in the great cities of Europe, South America and Japan. Now revenues flowed from all over the world, literally, to the man who had created the practical incandescent-lighting system. Millions were made happy by the usefulness and great convenience of the carbon filament lamp and blessed the name of Edison. His affairs were now so prosperous that at last he could look forward to relinquishing most of his purely business cares to other hands and going back to his laboratory table, like the incorrigible experimenter he was. Everything he touched, people said in those days, turned to gold. He could not but be aware of the broad change in his circumstances. It followed naturally that his tastes and interests, his whole way of life, changed gradually to suit his altered circumstances.

2

Six months had passed since the death of Mary Edison; more and more the widower of thirty-eight felt the difficulty of his position. He was left with three motherless children whom he could not properly look after; in any case, he had not the temperament to do it.

Marion, who attended a boarding school in New York for a while, was nearest to him and much in his company during the wifeless interval. At thirteen she was almost full-grown, and went out with him a good deal to theaters, restaurants, or on Sunday carriage drives. That he should want to see her often, that he should show an interest in her clothes or in the fanciful things she wrote in her diary was a delight to her.

“Why don’t you come down to my shop to see me? You’re not studying anyway,” he would say, for he seemed lonely then. And she would leave her lessons and come to the machine works on the East Side, bringing him his favorite five-cent cigars. She tried to appear as grown-up as possible and be his companion in leisure moments.

My father’s idea of my education was that I shouldn’t have any [she has said]. Or, at any rate, that I should get it by reading everything, as he did, perhaps beginning with Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, or Watts’ Encyclopedia.477

The two boys, however, he saw much less of; Tom and Will, at this period, lived at Menlo Park with their Aunt Alice. Having formed strong prejudices against formal or academic education, Edison saw to it that his sons, as well as his daughter, had as little as possible of it. He would have liked the boys to acquire the training of a mechanic or an artisan, according to the principles expounded in Rousseau’s Émile, which he had read with approval. The results in the long run were not such as to have gratified either Rousseau or Edison, America’s own “child of nature.” The sons by the first marriage now had no mother and knew their father very little.

In his friendships, it was observed, Edison was given to “sudden personal enthusiasms... impatience and impulsiveness.”478 At times different favorites, like new satellites, revolved around his sun. Where Johnson had formerly reigned, the stout Gilliland now sat as the master’s first “apostle.” It was probably true, as was often said of Edison’s intimates, that they often dreamed of becoming rich in his service; somehow, the Old Man would come through with a pot of gold for them all. But Johnson, nowadays, seemed more avid than any of the others to “pick up something on the side” — something more than the minor shares or bonuses Edison gave his associates — and joined with the young engineer Frank J. Sprague in forming the Sprague Electric Railway and Motor Company, a small business which grew out of the Edison enterprises.

Gilliland seemed different. The jovial man with the handle-bar mustaches was not only sympathetic, he was deferent to Edison; in experimental work he showed an intelligence attuned to the inventor’s. A deep fellow, yet humorous, and always quick with a pun. Though Gilliland often came to New York to work with Edison, his home was then in Boston, for he had some profitable business of his own in telegraph and telephone patents. Then there was his accomplished and beautiful wife, like her husband a native of Ohio, presiding gracefully over their home, which Edison visited often in the winter of 1885 on his trips to New England. One of the new friends he often saw at the Gillilands was a handsome young lawyer named John Tomlinson, who soon became Edison’s trusted personal attorney.

Under the civilizing influence of the Gillilands and Tomlinson the formerly unsocial man of the laboratories is found going out to buy a sixty-five-dollar coat (very dear then) and dressing for the evening. “For fear that Mrs. Gilliland might think I had an inexhaustible supply of dirty shirts, I put on one of those starched horrors procured for me by Tomlinson,” he confesses. He was used to shuffling about in oversized boots, but now admits that he has bowed to fashion and purchased “premeditatedly tight shoes.” They look nice, he concedes; but, he asks himself, “Is it not pure vanity, conceit and folly to suffer bodily pains that one’s person may have graces [that are] the outcome of secret agony?”

He who was always formerly so pressed for time, night and day, now sits for hours on end in a drawing room with elegant but idle ladies and gentlemen, enjoying light talk, listening to music, and even playing parlor games! One of the games is “mind reading,” which yields poor results. The ladies insist on talking about “love, Cupid, Apollo, Adonis, ideal persons. One of the ladies said she had never come across her ideal.” And Edison quips that she had better “wait until the Second Advent.”

A more rewarding pastime to which he was introduced, during a holiday with the Gillilands on the North Shore of Boston Bay, involved writing a diary. Each person in the party undertook to put down the truth, and only the truth, in his or her diary and then read it to the others. It is thanks to this that we have a precious fragment in Edison’s own hand covering ten days of the summer of 1885 in which he sets forth his thoughts of the moment, his emotions, his inventive fantasies.479

Here are snatches of his daydreams, of his uncontrollable imaginings: gigantic demons “with eyes four hundred feet apart”; hideous crawling insects or monsters; a preposterous machine to be inserted into some unnaturally thin woman’s joints to provide them with automatic lubrication, as with one of his steam generators. Then there are notes of jokes, more or less salty, such as Edison liked to produce on suitable occasions, and humorous speculations on recent developments in electrical science. The abandoned laboratory at Menlo Park, he learns, is now to be used for experiments in hatching chickens in an electric incubator. Edison exclaims to himself in mock indignation, “Just think of electricity employed to cheat a poor hen out of the pleasures of maternity. Machine-born chickens! What is home without a mother?”

His favorite relaxation, however, is to retreat to his room and get into bed with a miscellaneous assortment of books: Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister; Rousseau’s The New Héloise; Lavater’s Human Physiognomy; The Memoirs of Madame Récamier (“I would like to meet such a woman”); Hawthorne’s English Notebooks (too many ruined abbeys in them — “Perhaps I’m a literary barbarian?”); and finally, best of all, the Encyclopaedia Britannica (“To steady my nerves”).

With his new friends he also goes off to one of Boston’s old music halls, a form of entertainment he has always liked, sits in the “bald-head row,” and enjoys a display of “the usual number of servant girls in tights.” After the chorus has completed its long military maneuvers, the junoesque Lillian Russell makes her appearance. “Beautiful woman, beautiful voice,” is Edison’s appraisal. But with a touch of prudery he also remarks that the lady is said to have been married more than once.

Then there are sedate yachting and fishing parties in which he must join, the men clad in white duck, the ladies in long white dresses. But on one occasion the ocean spray blows hard, the ladies’ long dresses are thoroughly soaked, and they turn back to shore without any fish.

What has become of the Thomas A. Edison we knew, the man who labored like a Titan, chewing tobacco and spitting on the floor? How could he pass whole days in such politely frivolous diversions? Was he corrupted, bewitched? Certainly the charm of the Gilliland home and its circle held him at this period and distracted his mind. His hostess, as he writes, would greet him “with a smile as sweet as the cherub that buzzed around the bedside of Raphael.” But in truth there was another woman in the case, younger, even more beautiful, whose image would not leave his mind, as the diary reveals by many artless passages.

The thought that for all his fortune, he lacked such a home as the Gillilands’, with its cheerful talk and laughter, and such a homemaker as its mistress to care for his children and himself, was present in his friends’ minds as well as Edison’s. He was certainly one of America’s most eligible widowers. At news of the death of his wife, scores of unknown ladies wrote him letters expressing their pity at his bereavement and freely offering him their hearts and their fortunes. Sam Insull, in fact, was kept busy answering these fair correspondents, often sending them photographs of the inventor by way of solace.

The Gilliland couple, evidently with the tacit approval of Edison, now undertook to invite to their home a flock of marriageable females for the widower’s inspection. By ones and twos they arrived in Boston from as far off as Ohio and Indiana during the winter and spring of 1885 and marched into the Gilliland parlor, while Edison examined them one after the other. The game grew more and more engrossing, though Edison remained coy.

“Come to Boston,” he wired Sam Insull, who liked this sort of thing. “At Gill’s house there is lots of pretty girls.”480 There were, for instance, “two Hoosier Venuses,” one of them a blonde, like his late wife. Finally there appeared a striking brunette from Ohio, whom Mrs. Gilliland knew well, and whose visit was carefully planned. She was Mina Miller, the daughter of Lewis Miller, of Akron, Ohio, a wealthy manufacturer of farm tools. Mr. Miller was well known as an active and philanthropic churchman, for he was the cofounder — with Bishop John Vincent of the Methodist Church — of the Chautauqua Association. A colorful man in his own right, he had begun his career as a plasterer, educated himself to be a schoolteacher, and afterward became a successful inventor and manufacturer of agricultural implements. Samuel Smiles had made Mr. Miller’s career the subject of one of his essay-sermons on self-help.

As was so often the case in American families of recent fortune, Lewis Miller’s daughter Mina was sent to a finishing school in Boston, and then, for further improvement, on the “grand tour” of Europe, whence she had lately returned. She is described as having been in her youth “accomplished and serious, with a liking for charity and Sunday school work” — but also a veritable belle, with an imposing figure, “rich black hair and great dazzling eyes.”481

The first meeting of Edison and Miss Miller took place in the early winter of 1885; by prearrangement the girl was visiting with Mrs. Gilliland, whom she had known well in Ohio, when the inventor arrived from New York. The Gillilands had told him all about her.

Edison was talking to several men in the parlor, when Gilliland, who had left the room, came back and said to him, “Mina Miller is here and she is going to play and sing for you.” In a few minutes he returned accompanying the beautiful young woman, who swept into the drawing room like a great lady. It was well known that Edison would be annoyed when women, on first being presented to him, expressed wonderment and rapture at the honor, or paid him exaggerated compliments. The eighteen-year-old Miss Miller, however, greeted the great man with dignity, and, while he stared at her, returned his gaze with the utmost composure. On being asked to sing, she went at once to the piano and performed for the guests. She was far from being an accomplished musician, according to one witness, but what was impressive was the self-assurance and aplomb with which Miss Miller did everything.

The inventor, who was twice her age, on first exposure to Miss Miller’s charms and virtues, felt, as he himself said, “staggered.” Why this was so, just what was the nature of the electrochemical reaction that took place he could never explain. “Ask me nothing about women,” he wrote on a later occasion, “I do not understand them. I do not try to.” Not long after meeting Miss Miller, he sent an urgent telegram to Insull, in New York, asking that two photographs of himself be sent to Miss Miller in Boston.

Mina Miller Edison, Edison’s second wife.

Later that winter he was in Chicago, in connection with Edison Company business; the weather was bitter, he caught cold, and then became quite ill, staying in bed at his hotel for a week. Gilliland, who had accompanied him on this trip, thought his condition so serious that he sent for Edison’s daughter Marion. When Edison arose from bed, he was still extremely weak. It was then agreed that a winter vacation in Florida was indicated if he would restore his strength quickly. Mrs. Gilliland joined them, and Edison proceeded with his party directly from Chicago to St. Augustine.

He would have returned North within a few days, but that someone spoke to him of the tropical region of southwest Florida, of the Everglades and the Keys, then still a frontier zone. When he was told of the jungles down there, he thought he would surely find vegetable fiber that would be perfect for his incandescent lamp. Off he went, with his two friends and his daughter, for a journey of some four hundred miles on a rickety train, which on one occasion jumped the tracks in the deep pine woods and could not be moved for two days. At length they reached Punta Rassa, on the Gulf Coast, a tiny harbor for the cattle trade, with an old iron lighthouse facing it across the bay from Sanibel Island. Here he was told of plantations along the Caloosahatchee River, near the village of Fort Myers, where tropical fruit and palm trees grew, and even bamboo sixty feet tall!

Bamboo! Had he not sent agents to the Far East and Brazil in search of it? In a small sloop the Edison party pushed eighteen miles up the river, lined with moss-covered live oaks, to the exotic paradise of Fort Myers, then a hamlet with one general store and a wretched inn. In this sun-drenched scene of royal palms, mangoes, and giant tropical flowers, Edison, who had felt himself near death in Chicago, revived wonderfully. After prowling about the place for two days he determined to take an option on a site of thirteen acres along the Caloosahatchee and build a winter home there for himself.482

Wherever he went that season, he spoke of the perfections of Mina Miller. So much so that, as he noticed, it made his daughter Marion fierce with jealousy. “She threatens to become an incipient Lucretia Borgia!” he wrote in his diary. On his return to New York, he found that the thought of Miss Miller permitted him no sleep. He wrote in his jocular manner, “Saw a lady who looked like Mina. Got thinking about Mina and came near being run over by a streetcar. If Mina interferes much more will have to take out an accident policy.”

He had worked while others slept, and had become far more ill and exhausted than he realized. In the Floridian jungle Edison, like so many other weary travelers before and after him, had felt his strength and youth return. Like the suddenly awakened Faust, he felt he must now live in the sun and enjoy the love of a young maid. He decided that he must marry Mina Miller, bring his bride there, and build not only a winter home but a new laboratory to be placed in that fabulous setting of tropical flowers and palms. His beloved friend Gilliland must also live there and share his life. Gilliland enthusiastically agreed. Edison’s diary shows him, in the summer of 1885, buzzing with romantic schemes for his castles in the Everglades; he even attempts a flight of poetic prose, then mocks at himself:

Studying plans for our Floridian bower... within that charmed zone of beauty, where wafted from the table lands of the Orinoco and the dark Carib Sea, perfumed zephyrs forever kiss the gorgeous florae — RATS.483

Determinedly he wooed the young lady “via the post office,” a novel experience for him. Though he was uncommonly busy again that year with new lighting plant installations and space telegraphs for railroads and ships, he made prodigious efforts to see her. Her home was in Ohio; but in the summer the Millers regularly migrated to Jamestown, New York, to attend the gathering of the Chautauqua Association. Though Edison was “not much for religion,” as he said, he determined to visit that repair of evangelists in order to see her whom he now called “the Maid of Chautauqua.”

On arriving at Lake Chautauqua and meeting one of many ministers assembled there, Edison is reported to have said, “I am afraid we do not belong to the same denomination.” His outspoken irreverence posed something of a problem for his sweetheart’s father. “My conscience seems to be oblivious of Sundays. It must be incrustated with a sort of irreligious tartar,” he wrote.484 It was useless for him to go to church, since he was so deaf. In fact he jested that if he chose any church at all it would be the Roman Catholic, “because there you paid your money, and the priest whose business it was, looked after the rest.”485

Now, Mr. Lewis Miller had been so long and closely associated with Bishop Vincent, the head of the Chautauqua Association, that their children had virtually grown up together. There was a rival suitor on hand, a younger man than Edison, the bishop’s son George, who later became a distinguished educator himself. George Vincent, in fact, was considered to be destined for Mina since boyhood — until the middle-aged but impassioned inventor appeared upon the scene. It was Edison who was at her side during a crowded afternoon steamer excursion on Lake Chautauqua. The throng surrounded them closely, they could not be alone; and he could not hear her save when he was very close to her. But the inventor was once more equal to the emergency. As he related:

My later courtship was carried on by telegraph. I taught the lady of my heart the Morse code, and when she could both send and receive we got along much better than we could have with spoken words, by tapping our remarks to one another on our hands.

On another occasion soon afterward, he managed to take her out alone with him in a small rowboat. Mina Miller feigned resistance to her magnetic and ardent lover for a while, though with steadily weakening resolve.

By dint of much persuasive effort he then gained her parents’ consent to have her join him in a long excursion by carriage through the White Mountains of New Hampshire, the Gilliland couple acting as her chaperones, while his daughter also accompanied them. It was during this drive through the mountains that Marion saw her father tap out his proposal on Miss Miller’s hand, as he too testified:

I asked her thus in Morse code if she would marry me. The word ‘yes’ is an easy one to send by telegraphic signals, and she sent it. If she had been obliged to speak she might have found it much harder. Nobody knew anything about our many long conversations... If we had spoken words others would have heard them. We could use pet names without the least embarrassment, although there were three other people in the carriage.486

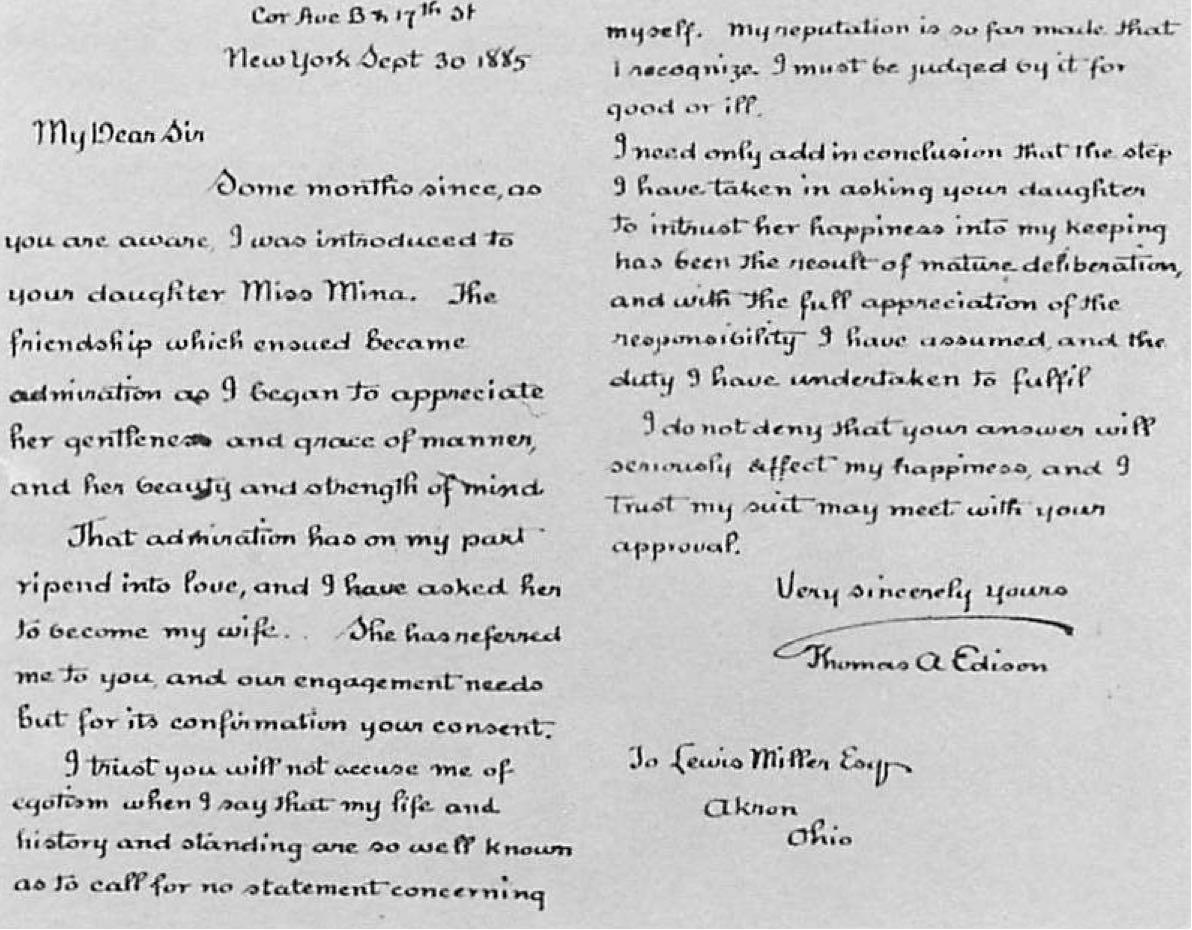

Mina’s consent was conditional upon her parents’ approval. Therefore Edison, upon his return to New York on September 30, sent off a formal application for her hand to Mr. Miller, which he evidently composed by dint of much labor and thought. Part of the letter, done in his manuscript hand, sounds as if written with the help of his secretaries (who may have drawn upon contemporary manuals of etiquette); but part is unmistakably and inimitably his own.

I trust you will not accuse me of egotism when I say that my life and history and standing are so well known as to call for no statement concerning myself. My reputation is so far made that I recognize I must be judged by it for good or ill...

Edison had made his proposal after mature deliberation; and he declared in conclusion that he had learned to love Mina, and that his future happiness depended upon Mr. Miller’s answer. The reply brought assurance of such happiness.487

Edison’s letter to Lewis Miller, asking his consent to Edison’s marriage to Mina. Courtesy Charles Edison.

The news of Edison’s forthcoming marriage to Mina Miller, the daughter of the Akron philanthropist, was soon out. In the autumn of 1885 it was perceived by his associates that the inventor was making extraordinary preparations for this new phase of his life. He was busy with plans for building a winter home in Fort Myers, Florida, and having lumber shipped for his projected laboratory. In order to land there and unload building material and equipment a pier extending some distance into the river must also be constructed. Since it was not easy to reach Fort Myers overland, he would go by boat; and soon he advertised for a sixty-five-foot steam yacht with two staterooms (though he gave up the idea when he saw what it would cost).

To his agents in Florida he sent instructions covering every exigency:

We will erect two dwellings [one was for the Gillilands] on the riverfront and place the laboratory and dwellings for workmen on the other side of the street... Our buildings are being made in Maine and will be loaded aboard ship at Boston. We will send four of our employees to superintend the work...488

Another matter that engrossed him that autumn was the purchase of a home magnificent enough to be the setting for such a bride as was Mina, and for his own improved station in life. The simple house at Menlo Park was out of the question now. He made two hurried visits to Akron to see her (though he never seemed fully at his ease in the parsonical circle of the Millers) and saw her again in New York when she visited the city in December, just before their marriage. He had given her the option of living in a big town house in the city, or in the country, and she had expressed a preference for a country house.

On a day when the snow covered the ground he drove with her to suburban West Orange to see a large estate he considered purchasing. It was called “Glenmont,” and had been built on a high ridge by a former millionaire merchant of New York at the staggering cost of $200,000. It was not a house, but a veritable castle of brick and wood in a style loosely called American Romantic, with spacious rooms, numerous outbuildings and greenhouses, and broad, landscaped gardens. Glenmont apparently suited Miss Miller’s ideas exactly. There was the further advantage that it could be purchased at a fourth of its original cost, since the improvident owner, a notorious absconder, had skipped the country with all his movable wealth, leaving the disposal of his house to defrauded creditors.

All this, and the bride’s jewels too, meant spending money like water, yet nothing daunted the inventor. Though not yet forty in 1886, he saw himself as one who was rising to the status of America’s ruling industrial barons, one who stood at the head of a great industry he himself had created. Henceforth, all that he undertook must be planned on the grand scale; his mode of life itself was to be transformed. There was to be not only the great mansion in suburban New Jersey, but also a vastly enlarged new laboratory to replace Menlo Park, furnished with the finest equipment in the world, and to be situated on the acres he had purchased in West Orange, within a half mile of his future home and his new wife.

In February, 1886, Edison’s friends gave him a last, very jovial bachelor’s dinner at Delmonico’s Restaurant in New York. Ed Johnson, Batchelor, Bergmann, Gardiner Sims, and others were present; hearty toasts were drunk, the party breaking up with the understanding that its members were to meet again on the twenty-fourth of the month, at the wedding ceremony in Akron.

All northern Ohio seemed to be agog over the event, as Edison arrived there to be wedded to an acknowledged belle of the region. From the entrance of the big Miller house in Akron Mr. Miller literally rolled out a red carpet extending several hundred feet to a knoll on the grounds that overlooked the city. By every train crowds of guests arrived, the spanking Miller carriages with their high-stepping horses meeting and bearing them away swiftly to the Miller home. The big front parlor was ablaze with flowers and resounded with the music of an orchestra; a whole corps of waiters had been brought from Chicago to serve the wedding lunch. The ceremony was performed under an arch of roses by a leading minister of the Methodist Church. Later that afternoon the couple drove around Akron, cheered by crowds along their way, and had their picture taken before boarding the train for Florida in the early evening.

The winter home in Fort Myers was not ready for them; conditions, at first, must have been rugged. But nothing whatever was heard from Edison for three weeks; he seemed to have vanished from sight like one enchanted. A secretary said:

We have written to him; we have telegraphed him. We get no response... We ask him questions requiring his immediate attention and that is the last of it. We are running the concern without him. He ignores the telegraph and despises the mail.489

In April they came back from Florida and Edison brought Mina to their new home in West Orange, that sprawling, red-painted chateau with its many gables, carved balconies, and stained-glass windows over which the second Mrs. Edison was to reign for many years as proud chatelaine. In character Glenmont was similar to those spacious residences of mixed architectural styles erected by the new rich of the 1870s and 1880s in Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Chicago, and along the Hudson River in New York — homes signalizing the status and power of the princes of oil, pork, iron, coal, railroads, and (now) electricity. It had a porte-cochere and a broad vestibule, vast living rooms, rich chandeliers, wide staircases, heavy red-damask-covered furniture, and masses of bad statuary, oil paintings by the yard, and bric-a-brac collected by its former owner. To be sure, an isolated lighting plant was promptly installed in it; and Mina Edison was to make it as bright as possible with flowers and pictures. To her this place was the appropriate setting for genius.

In speaking of the house at the time Edison said that he had intended to look for a country home costing no more than $20,000.

“But when I entered this I was paralyzed. To think that it was possible to buy a place like this, which a man with taste for art and a talent for decoration had put ten years of enthusiastic study and effort into — too enthusiastic in fact — the idea fairly turned my head and I snapped it up. It is a great deal too nice for me, but it isn’t half nice enough for my little wife here,” and he laid his hand on the arm of the beautiful young woman at his side. “So that secures the fitness of things.”490

Upstairs sitting room at Glenmont, Edison’s home in Llewellyn Park, as it appeared in 1907.

Many years later a famous European writer called at Glenmont to interview Edison and, in the course of their conversation, likened him to Faust.

“Faust!” exclaimed the inventor; then drawing his arm affectionately around his wife, he added with a twinkle in his eyes, “Ah, yes, Faust, and she is my Margaret.”491 But Mina Edison was, in reality, very different from the peasant maiden of Goethe’s drama. Her predecessor, Mary Edison, in her innocence and simplicity, more nearly suited the part.

Some pains had been taken with Mina’s upbringing so that she might be fit to play her part in good society. She was a young woman of indubitable strength of character and will, and entered upon the adventure of marriage with full awareness that her mate was one of the most noted of living men and of the duties she owed him. There was a good deal in her husband that she intended, nevertheless, to improve — if she could possibly do so. Under her sway his rough exterior would be gradually smoothed a little here and there, though it was a slow and difficult process. No power on earth could really turn this man into a tame parlor lion; to Mina’s regret he continued to shun the kind of social life she would have enjoyed.

“You have no idea,” she said on one occasion in later years, “what it means to be married to a great man.”

Life itself, the changing focus of his interest, his very different preoccupations, nowadays worked to bring about a change in his ideas and in his aspirations.

In his middle years the worker risen from the ranks of the poor was the lord of Glenmont and its handsome acres and possessed of a good and beautiful young wife of proper breeding. His ambitions nowadays were unlike those of the typical man of science and bore a resemblance rather to those of the Carnegies and Rockefellers, the ruthless captains of industry who were his contemporaries. He spoke, at about this time, to J. Hood Wright, a partner of Morgan, of his purpose of building up a whole series of new industries. To A. O. Tate, who became his private secretary after Insull’s promotion to an executive post, he also remarked, while gazing out of the windows of Glenmont, “Do you see that valley?”

“Yes, it’s a beautiful valley,” the other replied.

“Well, I’m going to make it more beautiful. I’m going to dot it with factories.”492