16 ~ The Edison laboratory, West Orange

1

During the boom times of the late 1880s in America, the frontier was vanishing, the settled territory of the country was expanding, the whole economy was growing at an unprecedented rate. Was there ever anything like the newly completed Brooklyn Bridge, or the young skyscrapers in Chicago, or Mr. Carnegie’s steelworks in Pittsburgh? Like a good American Mr. Edison, too, felt the urge to do things on a truly continental scale.

At this period, in 1886, the Edison Machine Works, which had been undergoing a sort of forced-draft expansion, and suffering, moreover, from labor troubles as well as growing pains, was moved from its location in New York City to vastly larger quarters at Schenectady, New York. One of Edison’s agents had found some locomotive works in this old Dutch community, on a tract along the Mohawk River near the Erie Canal, these works being then unoccupied because the several owners had quarreled and gone out of business. Schenectady’s Chamber of Commerce proved eager to invite in the Edison enterprise and helped to arrange for the sale of the property for $37,500, a sum far below its cost. The great presses and machine tools were then transported to Schenectady, and within a year all the Edison generator, motor, tubing, and insulation work was being carried on there by some eight hundred hired hands. A year later, the scientific journalist, T. Comerford Martin, described the Schenectady works as “a vast establishment of noble machine shops... where the prosaic and marvelous jostle each other... one of the greatest exemplifications of the power of American inventive genius.”493 The Schenectady works grew with the rapidity of a Western mining boom town, until they fairly overflowed with busy artisans and machines of every kind. Some referred to them as “the cathedral shops” because of their lofty ceilings which permitted the use of great cranes overhead.494

The next year there was the new laboratory to be built at a site in West Orange’s quiet Main Street, a half mile from Edison’s new home. His plans for this were on a scale that completely dwarfed the wooden “tabernacle” of Menlo Park. The new conception, the altered scale of his ideas at this period may perhaps be illustrated by an incident that occurred some years later, when a noted French inventor of electrical devices, Edouard Belin, came to visit Edison at the West Orange institution. After showing the visitor about the place, Edison, during a friendly discussion, advised him to center his inventive labors on products that would come into universal use, so that he could “make a lot of money out of them.” And what would he do with the money, the other asked, since he had enough for his needs? “You could build a fine laboratory, where you could have everything you desire and be able to hire the greatest technical experts as your assistants... a place in which you could invent anything that came into your head, regardless of expense.”

The French inventor mentioned that he had a small establishment and was content with it. “I already have a rather nice laboratory,” he said.

“But if you had unlimited money,” Edison insisted, “you could build a laboratory ten times as big... and you could do ten times as big things.”495

Such was the Edison of the middle years, after his marriage and the acquisition of Glenmont. He believed that with a larger scale of operations he could more easily make “useful things that every man, woman and child in the world wants,” and would buy “at a price they can afford to pay.”

The West Orange laboratory buildings, when completed after more than a year of construction work, aggregated ten times the size of the humble establishment at Menlo Park. They constituted then the largest and most complete private research laboratory in the world. In a notebook which he kept while construction was still in progress, Edison described his whole project with enthusiasm:

I will have the best equipped & largest Laboratory extant, and the facilities incomparably superior to any other for rapid & cheap development of an invention & working it up into Commercial shape with models patterns & special machinery. In fact there is no similar institution in Existence. We do our own castings forgings Can build anything from a lady’s watch to a Locomotive... Inventions that formerly took months & cost large sums can now be done 2 or 3 days with very small expense, as I shall carry a stock of almost every conceivable material.496

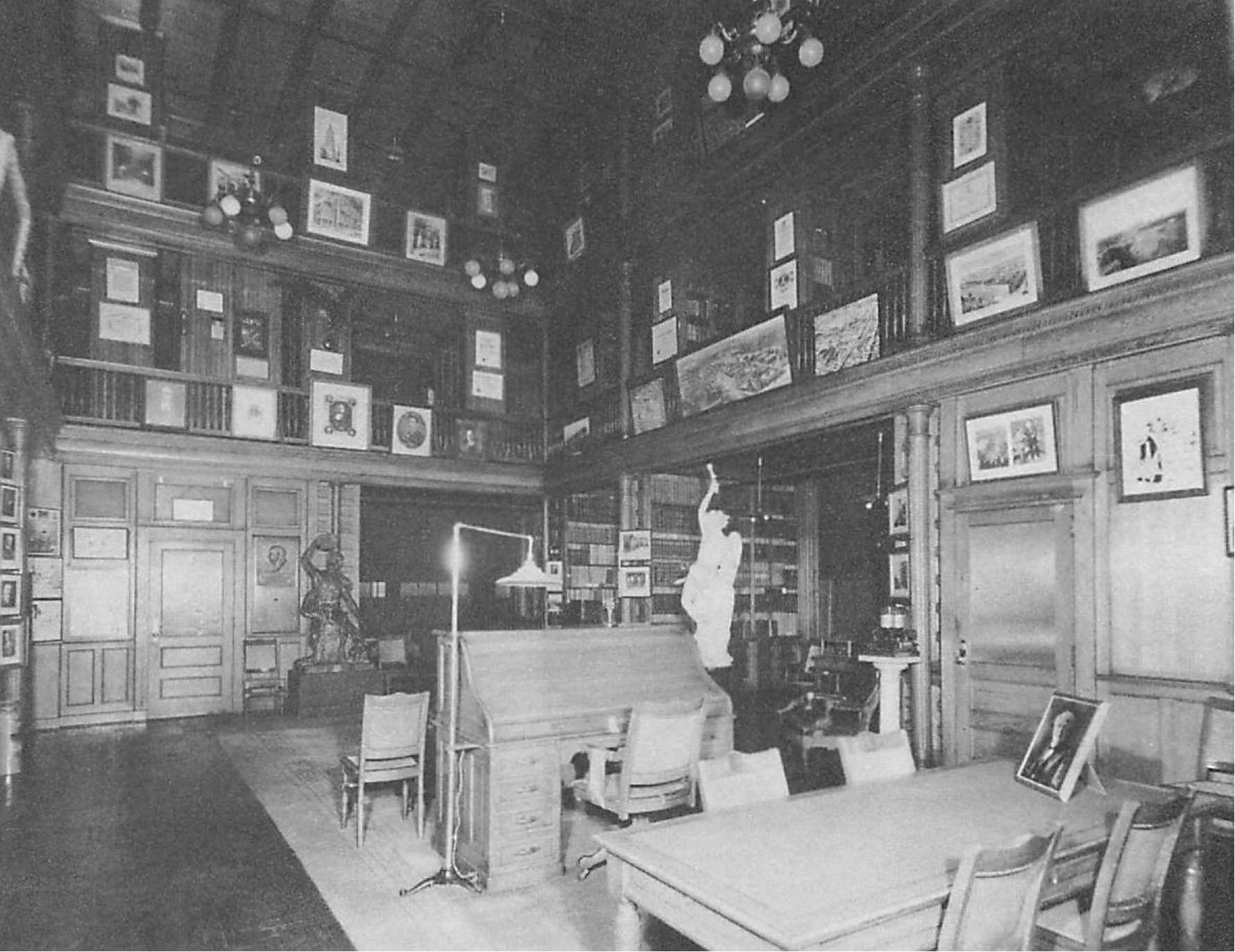

The main building was of brick construction, about 250 feet long, three stories high, and having 60,000 square feet of floor space. It contained large machine shops, an engine room, glass-blowing and pumping rooms, chemical and photographic departments, rooms for electrical testing, stockrooms, and in its main wing a spacious office and library. The library, a great hall with a thirty-foot-high ceiling and two tiers of galleries rising from its main floor, contained 10,000 volumes. With its stores of minerals and chemicals in glass cases it was a museum and sample room in one. At the same time, four more long, one-story structures were laid out adjacent to the main building and at right angles to it, the whole group making a yard, or quadrangle, enclosed by a high picket fence with a guard posted at the entrance gate. The work here was now carried on with a fair degree of secrecy, visitors being admitted only on invitation.

Since everything about Edison was “prodigious” to the newspapers of the time, the contents of his new laboratory were reported in the usual superlatives, as embracing

eight thousand kinds of chemicals, every kind of screw made, every size of needle, every kind of cord or wire, hair of humans, horses, hogs, cows, rabbits, goats, minx, camels... silk in every texture, cocoons, various kinds of hoofs, sharks’ teeth, deer horns, tortoise shell... cork, resin, varnish and oil, ostrich feathers, a peacock’s tail, jet, amber, rubber, all ores, metals. Of one jobber [so the inventor gaily told the reporter] he “ordered everything from an elephant’s hide to the eyeballs of a United States Senator.”497

Menlo Park, within its small compass, had provided the first center for organized “industrial research” in the world. For seven years it epitomized the romance and the ardors of pioneering in new fields of applied science. The new laboratory, a whole community of buildings dedicated to applied science, was huge indeed by comparison. It was not fated, however, that it should outshine the small place at Menlo Park in the quality and brilliance of inventive work performed.

For one thing, a staff of forty-five to sixty persons assisted the inventor at West Orange. They ranged from scientific specialists, like Dr. Arthur E. Kennelly and the well-known chemical consultant J. W. Aylsworth, down to draftsmen, mechanical assistants, “bottle-monkeys,” and unskilled laborers. Edison still kept a tight rein on everything being done in his laboratory, but inevitably the work had to be departmentalized; various persons or teams were constantly engaged in making tests or trials and writing detailed reports on different experiments going on concurrently. Edison therefore had to give an increasing part of his time to administrative work as the director of his staff.

At Menlo Park he was able to see at a glance what every one of his dozen assistants was doing in the one long room. Now, every morning after going through his mail, he would have the men in charge of different experiments come into the library one by one and report on the work in progress. He was always able, in a remarkable degree, to shift his attention quickly from one line of investigation to another that was entirely unrelated, asking questions rapidly, giving instructions, and making decisions as rapidly. It was also his habit, at least once a day, to make a tour of the different departments and with his own eyes study the work being done. Nevertheless, he was forced to depend more than before on specialists, such as Aylsworth in chemical studies, or J. W. Howell in electric-lamp research. These were very able men, who did fine things. But they were not Edison.

His own passion for experimentation never flagged. From conferences or supervisory work on matters pursued by his assistants, he often would escape to an upper room of the main building, a sparsely furnished place littered with instruments and materials of all sorts. Here he would remain alone, or with at most one mechanical assistant, engaged in lengthy studies of the favorite subject of the moment. Most of the time, however, he was to be found seated at his huge desk in the center of his library, near its great marble fireplace. After some years, with the addition of many sculptures, medallions, and paintings of the inventor, as well as mahogany and yellow-pine furnishings, the library acquired the cluttered character of most late-Victorian interiors; but it was always deeply stamped with Edison’s personality. One day someone planted ivy outside the laboratory walls; it climbed to the roof, spreading everywhere about the whole group of buildings, so that the place came to resemble an abbey.

The library at the West Orange laboratory. Edison’s roll-top desk is in the center. The bronze statue to the left of the desk portrays Orpheus laying aside his lute for a phonograph record. The statue to the right, with the uplifted light bulb, is called The Triumph of Light.

The strategic importance of Edison’s original model of the private research center, as handmaiden to technology, was quickly grasped by the masters of some of our large industrial corporations. In 1881, the inventor Alexander Bell, for example, on receiving a prize of $10,000 in honor of his telephone work, established a small general research laboratory of his own in Washington, D.C., in imitation of Menlo Park. Out of this first center grew up the vast Bell System Laboratories. Others also imitated Edison in pursuing invention systematically; the early ones were the Thomson-Houston Company and George Westinghouse, who were already competing in the electrical equipment field. In the 1890s and prior to World War I, however, research work in the corporate laboratories was largely subordinated to the owning company’s special needs; and despite the advantages in large staffs and elaborate instruments, their accomplishments in those years remained somewhat unimpressive. Until almost the turn of the century the Edison Laboratory continued to be unique among private industrial laboratories, as a center of “general research on inventions,” with a varied program that might include anything from electric locomotives to phonograph needles.

2

One of his major preoccupations in the spring of 1887 was with renewed experimental work on his own phonograph. For nearly ten years the primitive tin-foil phonograph had remained only a scientific toy, now forgotten even by the entertainment parlors and country fairs that had once exhibited it. It was a beautiful concept, nonetheless, that of the preservation and reproduction of sound, and one that continued to fascinate men. In such a case, the original inventor having apparently neglected to improve his invention, it was inevitable that other skillful hands would take it up.

At the laboratory of Alexander Bell, recently established in Washington, his cousin Chichester Bell, a chemist, together with Charles Sumner Tainter, an able technician, devoted themselves for several years to the task of perfecting Edison’s phonograph. In June, 1885, they applied for a patent on a talking machine which they named the “graphophone.” In place of tin foil, whose impressions were faint and easily effaced, they introduced wax as a recording substance, which they imposed on cardboard and mounted on a cylinder. Their recording stylus, like Edison’s, moved vertically up and down in the groove, but instead of indenting or embossing its vibrations, “engraved,” that is, cut them into the waxed record, which they claimed as a new process; and whereas Edison’s stylus was rigid, theirs was loosely mounted so that it floated along without scraping too much. After receiving the award of their patent in May, 1886, Bell and Tainter decided to approach Edison privately and seek to enlist his cooperation in promoting the improved talking machine as a joint undertaking. Theirs was still a crude affair, but it sounded distinctly better than the tin-foil instrument; they also contrived to turn the cylinder at a constant speed, either with a treadle or a motor, which was more reliable than Edison’s hand crank.

Edison’s secretary, Tate, describes the proposals they brought:

They said that they fully recognized the fact that Mr. Edison was the real inventor of the “talking machine”; that their work was merely the projection and refinement of his ideas, and that they now wanted to place the whole matter in his hands and turn over their work to him without any public announcements that would indicate the creation of conflicting interests. They were prepared to bear the costs of all experimental work... and provide all the capital essential for its exploitation. And for all this they asked to be accorded a one-half interest in the enterprise... Though they had tried to differentiate their instrument from his by calling it the Graphophone, if Mr. Edison would join them they would drop this name and revert to the original designation.498

Reasonable though this proposition seemed on the surface, it made Edison furiously angry. He declared roundly that he would not deal with Bell and Tainter on any terms, and called them “specalators” who were bent on stealing his invention. A model of their machine had been left with him, and aside from their improved stylus, he found nothing new. It was astonishing to him that the Patent Office had awarded them a patent.

In truth the model of the “graphophone” of 1885, when examined today in the Smithsonian Institution, shows a startling resemblance to Edison’s phonograph of 1877. When, several months later, Colonel Gouraud cabled Edison from London, saying that he had been invited to head a British agency for the Graphophone Company, and inquiring if Edison approved, the father of the phonograph dictated a thunderous dispatch in reply:

Have nothing to do with them. They are bunch pirates... Have started improving phonograph. Edison.499

He had been literally “shocked into action,” as Tate observed. The phonograph was his “baby.” After having neglected his paternal duties toward it, owing to the pressure of so many other, larger affairs, he went back to his laboratory table again to consecrate long hours through most of 1887 to the phonograph. It might have been profitable for him to join forces with the Bell group, which now had ample resources. They, on the other hand, would be driven to change their talking machine drastically in order to avoid infringement on his patent rights. But Edison was nothing if not competitive in the arena of invention. He would fight them to the death. Like that imperious old railroad magnate, Commodore Vanderbilt, in a similar emergency, he vowed that he would not bother to sue his adversaries, but would ruin them — by making a better machine.

For most of two years experiment with the phonograph was given priority in the laboratory over many other affairs claiming his attention. And he was happier thus, as the engineers phrase it, with “his belly at the drawing table again”; for there were limits to his interest in purely commercial and industrial affairs, or in just “running wires” for one new lighting plant after another in different towns. In any case the light and power business was growing by itself in charge of his lieutenants, with Sam Insull, the sharpest of them, handling the business at Schenectady.

As was his practice, Edison began by establishing clearly in his own mind a concept of what the popular need and use of an improved phonograph would be, planning his line of development accordingly. The principal use of his invention, in his judgment, would still be as a business machine for dictating letters and commercial records. The “craze” of 1878 for recordings of fragments of popular music or vaudeville humor seemed to have passed off; and in any case, he disliked that business. Success would depend on accurate recording and faithful reproduction; he must find, principally, an improved material for his records, something much better than tin foil. He foresaw also that facilities for duplicating records in large volume would be of the utmost importance; it would also be necessary to find some means of re-using records if the machine were to be made practical for business dictation.

Having mapped out his campaign, he took steps to reorganize the old Speaking Phonograph Company of 1878, inviting its few shareholders to exchange their stock for shares in a new corporation which would take over the patents of the old concern. His new favorite, Ezra Gilliland, worked with him in experiments on the new machine. Gilliland told Edison that the new phonograph would be a splendid commercial affair some day, if a practical man were to promote it and give it all his time. He then pressed Edison to appoint him as the new company’s general sales agent, or executive manager. In a most generous spirit, and largely because he felt Gilliland was his trusted friend, the inventor granted him this key position, and signed a contract to this effect, which was executed by Gilliland’s friend, Tomlinson. This well-spoken young patent lawyer had become Edison’s personal attorney in 1884, in place of Lowrey. Afterward when trouble arose people would remember that Tomlinson was a man who “never seemed to be looking at you directly when you spoke to him,” perhaps because of a slight cast in one eye.500

In the many clauses of his basic phonograph patent of 1878 Edison had enumerated various materials that could be used for records, waxed substances among them. As a substitute for the old tin-foil sheet he now devised a hollow cylinder of a prepared wax compound, with walls about a quarter of an inch thick. The composition of this wax-compound record, or “phonogram,” as it was then called, demanded infinite pains and hundreds of trials, the chemist Aylsworth furnishing Edison more help than any other in this work. Wax permitted closer grooving. In place of the old recording needle Edison then introduced a much harder cutting tool, which made “hills and valleys” at the vibration of the diaphragm; and for reproduction he employed, after a while, a somewhat blunt sapphire stylus. In the old machine there had been crude adjustment screws to hold the needle in place; now he devised a quite ingenious “floating weight” or flexible pickup mechanism that held the stylus down with a light touch. His recording process was so skillfully adjusted that grooves in the wax record were only one thousandth of an inch deep. Thus persons putting his machine to use for business dictation could shave their records down with a cutting blade provided for that purpose and re-use their records many times.

The idea of the floating stylus, it has been observed by a later commentator, was in all likelihood borrowed from Sumner Tainter’s original device for his “graphophone.” Edison may have felt that, inasmuch as his adversaries were trying to take over his basic invention, turn about was fair play. In fact, Bell and Tainter soon dropped their waxed cardboard record and again appropriated one of Edison’s useful ideas, that of the solid wax record.501

A more original piece of mechanical invention involved a new process for duplicating records in large volume. The great trouble was that the wax mold used for the original, or “master” record, was a nonconductor and could not be electroplated. After many years of study, Edison and his assistants (in 1903) worked out an ingenious duplicating process which he called “vacuous deposit.” Under this system the original record mold of wax was placed in a vacuum chamber, with a piece of gold leaf suspended on either side of it; high tension electricity was then discharged between the two gold leaf electrodes, while the record mold revolved. The electric charges vaporized the gold leaf and deposited it on the record mold in a film of tissuelike thinness. Upon this gold film, which faithfully represented all the original record grooves, a heavier deposit of another metal was then electroplated, so that — once the original mold was taken out — you had a very solid and durable negative mold, with which almost any number of positive wax copies could be duplicated.502

In testing results on the improved phonograph Edison had the great problem of trying to hear distinctly despite his deafness, which was total in his left ear. He would place his right ear — whose hearing was limited — in contact with the instrument itself or at its horn; or at times he would bite into the horn with his teeth, thus permitting the sound vibrations to be carried through the bones of his head to his hearing nerve. “It takes a deaf man to hear,” he would say grimly. Batchelor and Gilliland also served as his ears, by reporting results under different conditions.

The laboratory notebooks show him compiling a long list of “complaints” against his evolving phonograph:

Crackling sounds in addition to continuous scraping due, either to blow-holes, or particles of wax not brushed off — poor recording — uneven tracking — dulling of the recorder point — breaking of glass diaphragm — knocking sound: chips in wax cylinder — humming sound, due to motor.

In painstaking fashion he worked to eliminate these defects one by one, inventing various new stratagems and devices by which the first simple talking machine became more responsive and lifelike. Whereas the original discovery of the phonograph principle had been accomplished in a short time, a few weeks at most, the process of refinement in the second phase stretched out tantalizingly into months and even years. All these changes in detail and in mechanical design were incorporated in a series of approximately a hundred more patents covering his later phonograph models.

After about six months of hard work, in October, 1887, Edison felt he was far enough along the road to hurry off some of his customary advance bulletins for the press, serving notice to all the world that he had never really abandoned his “favorite invention” and that his perfected phonograph would be making its debut almost any day now. Though forced to throw overboard everything for the electric business, he had borne the phonograph for ten years “more or less constantly in my mind.” In this case, the publicity was shrewdly timed to forestall, or at least to embarrass his adversaries, Bell and Tainter, who were reported to have made real progress in improving their own machine. But the snowy winter went by and further press notices that the new Edison phonograph would be ready “within two weeks” proved once more to be premature.503 Though the rival group had a year’s head start, they too had met with much difficulty in making their machine foolproof and also in promoting it, very likely because potential investors or customers were holding back to see what new miracle America’s Wizard might yet produce.

In the early spring of 1888 Edison thought he had improved his machine to a point that would permit him to raise capital and launch it as an industry. A delegation of financiers was therefore invited to visit West Orange and inspect the new phonograph, rumors of which had already whetted their financial appetites. In the group were Jesse W. Seligman, of the important New York banking firm of J. & W. Seligman, as well as D. O. Mills and Thomas Cochran. Unknown to the inventor, his assistant John Ott at the last moment had substituted for the original apparatus what he considered a superior diaphragm, recently perfected in the shop; he had also changed the recording stylus for a finer instrument, but neglected to change the old reproducing stylus, which was of the broad or blunt variety.

All unaware, Edison in his library opened the demonstration by making a speech into the machine in the low tones used in dictation, announcing the serious purposes he had in mind for the phonograph and describing its splendid business prospects. Then he switched diaphragms and needles and began to play it back. But the reproducing needle proved to be too broad to enter the groove that had just been made and merely scraped along its edges, so that the phonograph gave forth only a continuous hissing sound — which sounded positively derisive. “Edison looked astounded and perplexed. He examined the instrument carefully but could find no defect. He was bewildered,” as a witness of the scene wrote. The same machines had been working quite adequately an hour earlier. The group of financiers, after waiting about, politely made their departure, saying they would return when he had located the trouble; but they never came back.504

Meanwhile, in April, news came that Bell and Tainter had finally sold out their graphophone patent to a millionaire manufacturer named Jesse W. Lippincott, and that he was going to promote the sale of the machine with great vigor. Edison now spurred everyone in his laboratory to the utmost exertions. More than money, as we have seen, he loved to win a stiff “horse race” for the honor of an invention.

As the spring of 1888 advanced, the pace of activities at West Orange increased. Edison and Gilliland worked together over the development of a small motor that was to turn the phonograph cylinder at a constant speed. A governor and a flywheel for the regulation of speed were also devised.

In testing his approved apparatus, Edison was perhaps the first to make records by famous musical artists. For all his bad hearing and want of musical education, he had very decided opinions on this art. He detested Wagner, but loved Beethoven. Emmy Destinn, to his mind, had “no voice,” and Caruso he considered an indifferent singer. The tremolos of Italian tenors were profoundly annoying to him, and coloratura sopranos no less so. What he feared was that such tones would make his recording stylus jump over the ridge of the record groove. “I hate catcalls,” he said, referring to sudden changes of volume, “they are apt to call up the unknown.” Other emphatic remarks in his notes assailed the “quaver” in the Italian dramatic style, which he was determined to teach singers to renounce. An operatic singer, in his view, was not required to “yell at the villain to stop murdering Leonora, because the people who listen to the phonograph can’t see the villain murdering her anyway and are not holding their breath.” He also wrestled with the problem created by orchestral accompaniment, which seemed to him to be “booming the cannon around the cry of a singing mouse.”505

The boy prodigy, Josef Hofmann, then twelve, came and played the piano before Edison. After him came Hans von Bülow, the most famous pianist of his era, to perform a brief Chopin mazurka, and to listen through the tubes as it was played back. Many years later, Edison, recollecting the audition, claimed that he had actually accused Bülow of having played a false note! When the artist protested heatedly, Edison cried out to his assistant, “Put on the wax,” and they played the record over again. When Bülow heard the alleged wrong note he “fainted dead away.” Edison then threw water in his face; whereupon the famous executant, reviving, left the laboratory without a word — “and that was the last I ever heard of the great von Bülow.”506 Conceivably the pianist may have been moved by his sense of outrage at the poor reproduction of his playing. Though the talking machines of 1888 showed a considerable technical advance compared with the first phonograph, they had serious limitations and encompassed but a small part of the tonal spectrum.

Henry M. Stanley, of African fame, a sternly religious little man whom God had brought safely through the jungle, also visited the Edison Laboratory about this time and spoke a few grave words into the talking machine. Then he turned to the inventor and said, “Mr. Edison, if it were possible for you to hear the voice of any man... known in the history of the world, whose voice would you prefer to hear?”

“Napoleon’s,” replied Edison without hesitation.

“No, no, I should like to hear the voice of our Saviour,” said Stanley.

“Oh, well,” laughed Edison, “you know, I like a hustler!”507

But to return to the War of the Phonograph, affairs approached a crisis by June, 1888. The American Graphophone Company, under Lippincott, was already offering its wares on the market; the Edison organization made public charges that its patent had been infringed upon and announced that it would soon be ready to put its own superior machine on sale.

At this point, Edison apparently had some afterthoughts about his “perfected” phonograph. Calling together his veteran assistants, he informed them that they were expected to stay on the job with him day and night until the new machine had been brought up to certain standards he had set for it. Somehow, news was soon circulated in the metropolitan press of the herculean exertions being attempted at West Orange, and of the last wild charge of the Edison team upon the sound-producing problems of the phonograph. Although reporters were barred at the gate and told that no one could see him, not even his wife, the newspapers during five days carried regular bulletins describing the great inventor’s “frenzy” and the “orgy of toil” endured by his associates locked within the Edison Laboratory.

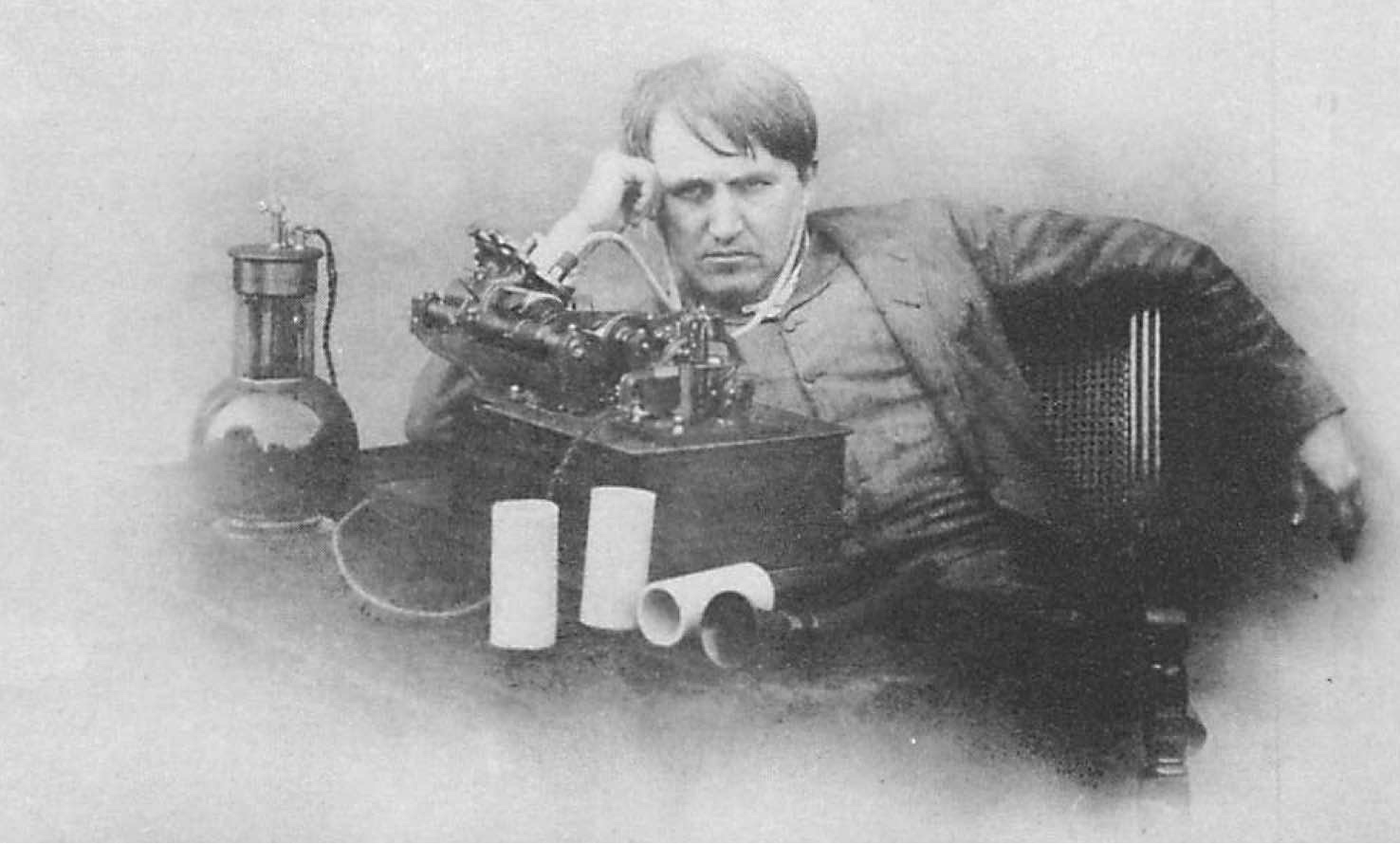

This famous endurance run was commemorated by a large photograph of Edison, said to have been taken “as he appeared at 5 a.m. on June 16, 1888, after five days without sleep.” It pictured him sprawling over his table, while listening to his finished phonograph through earphones, in an attitude of great fatigue, his head supported by one hand, his hair tousled, save for the long cowlick that fell habitually over his brow. The set of his jaw was thought to resemble the expression attributed to the most celebrated of modern military conquerors at the end of a victorious battle. An oil painting made after this photograph, in which the artist consciously tried to represent him as “the Napoleon of inventors,” was soon afterward widely distributed as an advertising poster by the Edison Phonograph Company.

Much-publicized photograph of Edison, “as he appeared at 5 a.m. on June 16, 1888, after five days without sleep,” working on the improved model of the phonograph. Actually the vigil lasted seventy-two hours.

Never before or afterward did Edison’s capacity to dramatize his career in the public mind, and to generate myths about himself, work to better effect. Before the coming of the famous American public relations counselors (of the type of Ivy Lee) Edison was a master of free publicity, received as much of it as he could possibly use, and, whatever he might say to the contrary, remained avid for it, generally avoiding spending money for paid advertising space as long as he could.508

The “five-day vigil” was a slight case of exaggeration. The laboratory notebooks do, however, furnish evidence of a “stretch of seventy-two hours” ending June 16, long enough by any standards.

On May 31, 1888, at a time when the inventor still seemed overborne by the problem of the new phonograph, excitement of a different sort centered at Glenmont, for on that day, the first of the three children Edison was to have by his second wife was born. It was a girl and was named Madeleine. Edison had interrupted his work to await the arrival of the child, remained for a time at his wife’s bedside, then hurried back to his laboratory. A few days later he had gone into his all-night sessions with the talking machine.

By now Mina Edison was more fully aware of what kind of great man she had married. Accustomed to a cheerful home, in which she played a leading part in a large family of eleven children, and to a busy social life, she must now spend her days and nights much alone in the big mansion on the hill at Llewellyn Park. There were few diversions, no games, and almost never any social gatherings here; only the servants, and some of the Miller relatives visiting her occasionally. She would be better off when she had more children of her own. The children by Edison’s first marriage did not enjoy staying at Glenmont. Marion, only a few years younger than her stepmother, was at a difficult age and attended boarding school or traveled in Europe with a governess. The two boys after a while spent much of their time in the home of their aunt, Mrs. Holzer, at Menlo Park, or at the farm of Uncle Pitt Edison in Michigan, when they were not away at school.

As Mina Edison said in later years, the conditions of her marriage constituted a great challenge. With her deeply imbued sense of duty she recognized that her husband’s career always came first. Such efforts as she made to soften or control him soon found their limits, for as he had once said, no woman could ever “manage” him. Evening after evening she would wait in vain for him to come home to dinner, then send him some warm food by the coachman.

A more resolute woman than his first wife, Mina is described as having forced her way into the laboratory and faced Edison down, on one occasion, when she discovered that the tray of tempting food she had sent him was untouched. “Now, Thomas Edison, you have just got to sit down and eat your dinner!” she exclaimed. She was loyal, and he, despite his teasing habit, was most affectionate with her. But when they were grown old, she did not shrink from admitting publicly that he was “difficult.” In a very apt phrase she once called him “my impatient patient one.”

Around the time of the coming of the new daughter and the new phonograph, Colonel Gouraud, Edison’s English impresario, arrived in West Orange for a business conference with the inventor. Shortly after he returned to London, he received from Edison, in place of the letter or cablegram he had expected, a dictated “phonogram,” reporting with great satisfaction the safe arrival of both “babies”:

In my Laboratory in Orange, N.J.

June 16, 1888, 3 o’clock a.m.

Friend Gouraud: This is my first mailing phonogram. It will go to you in the regular U.S. mail via North German Lloyd steamer Eider. I send you by Mr. Hamilton a new phonograph, the first one of the new model which has just left my hands.

It has been put together very hurriedly and is not finished, as you will see. I have sent you a quantity of experimental phonogram blanks, and music by every mail leaving here...

Mrs. Edison and the baby [Madeleine] are doing well. The baby’s articulation is quite loud enough but a trifle indistinct; it can be improved but it is not bad for a first experiment.

With kind regards,

Yours, Edison509

In England, at the time, the father of the phonograph was probably the best known American in civilian life. At his offices in London, now called Edison House, Gouraud gave demonstrations of the new apparatus that made a tremendous impression. These would begin with an introductory speech by Edison himself followed by records giving the silvery voice of Mr. William Gladstone, the Prime Minister; of Robert Browning reciting his verses (but forgetting his lines); and of Sir Arthur Sullivan showing his wit — but also, in serious vein, prophesying the horrors of mass entertainment:

I am astonished and somewhat terrified at the results of this evening’s experiments — astonished at the wonderful power you have developed, and terrified at the thought that so much hideous and bad music may be put on record forever!510

Edison said, “I don’t want the phonograph sold for amusement purposes. It is not a toy. I want it sold for business purposes only.” Nevertheless it was the entertainment side of his invention that the world wanted most. When this was perceived, the Edison organization later sold many music records, but did nothing to raise the standard of the music it chose to reproduce. Others applied the machine to the distribution of grand opera airs and vocal or instrumental music by serious artists. When, after several years, Edison learned that such things were being attempted in Germany, he at first refused to believe it.

The wax records of the new phonograph ran all of two minutes in those days, and could carry the volume of a brass band, or the warblings of a mockingbird. A typical picture of the Phonographic Age, often appearing in illustrated newspapers, was of two bearded gentlemen, each holding one tube of a talking machine to his ear, while gazing at the other with a rapturous expression. They were listening to “Home, Sweet Home.”

3

The circle of Edison’s old laboratory associates was evidently much agitated at the promotion of his new favorites, Gilliland and Tomlinson, to a dominant position in the reorganized phonograph company. The minority shareholders had been asked to exchange their shares for stock in the new company, but Edward H. Johnson and several others protested at the decision to place its management in the hands of Gilliland. “It is not a matter of money, but of wounded pride,” wrote Johnson. Edison, he said, was forsaking those who had shown their loyalty to him through long years and was giving his trust to persons who, for their selfish advantage, kept close watch over him, spied on him, and even intercepted messages sent to him by his old partners.511 In the end, Edison paid Johnson and several others cash to induce them to turn in their stock. He ascribed Johnson’s complaints to jealousy of Gilliland.

He himself felt a growing resentment at Johnson, who, having recently become the president of the Edison Electric Light Company, seemed bent on feathering his own nest as much as possible. In 1884 Frank J. Sprague and Johnson had set up, on a shoestring, the Sprague Electric Railway and Motor Company, in which Edison had no interest, for he had his own Electric Railway Company. Sprague had designed an excellent stationary motor used principally for elevators; his partner Johnson, through his connection with the Edison organization, pushed the sales of the Sprague motors, which were manufactured by the Edison Machine Works in Schenectady, as subcontractor. Then Sprague entered the traction field by inventing a motor specially designed for streetcars. Here he competed, in some measure, with the Edison-Field company, which, in contrast with Sprague’s, was then almost moribund. By his successful installation of a modern electric streetcar line in Richmond, Virginia, in the autumn of 1887, Sprague set the whole pattern for large-scale electric traction development — a field which Edison had tried to cultivate earlier. In temperament, Edison and the brilliant younger man proved to be incompatible. Sprague had the impression that Edison, at about this period, ceased to be progressive in matters of electrical science; while Edison held that the other tended to create dissension in the once “happy family” of his associates. At length, in 1889, the first Sprague company was bought out and merged with the Edison manufacturing organization, Sprague departing to organize another successful electrical manufacturing company of his own. Johnson also departed not long afterward. Edison said at the time that the whole Sprague-Johnson venture into motors and traction had been “a galling thorn among all the boys, and as I told you, would break up the old association.”512

In Ezra Gilliland, however, Edison saw the devoted business manager and promoter he, as an inventor, needed so badly. With the help of this trusted friend, he hoped that he might be permitted to give up many of his present business cares and go back to purely inventive research.

Capital was always desperately needed for the promotion of the Edison inventions. Gilliland undertook to raise the money needed for the production of the new phonograph, and promised to protect Edison’s interests in any transactions entered upon. One day in the spring of 1888 the bland, paunchy man turned up with a veritable angel, the same Jesse W. Lippincott of Pittsburgh who had recently bought the Bell and Tainter patent rights for $200,000. Formerly a successful manufacturer of glass tumblers, Lippincott had sold out his business for a cool million to one of those “trusts” that were then taking over almost every going industry in America, from barbed wire to mortuary caskets. The phonograph appealed to him as something new, in which he could put his money to work again. But on learning that there were prospects of a lawsuit with Edison, he had concluded that it would be better to combine forces peacefully than to go to war. Why not a Phonograph Trust? A proper venture in those days before the passage of the Sherman Act of 1890.

Impressed, no doubt, by the widely publicized “five-day vigil” at the Edison Laboratory, Lippincott approached Gilliland with an offer to buy the Edison phonograph rights in America. The inventor allowed Gilliland and Tomlinson to negotiate as his authorized representatives with the Pittsburgh entrepreneur.

About ten years before, during the 1870s, Edison had had a disastrous experience as a result of having put his trust completely in a certain patent lawyer of Washington, to whom he had sent papers covering numerous patent applications for minor telegraphic devices. When some time had gone by, he discovered that the lawyer had sold the numerous patent applications for small sums of cash to other parties, executing the patents in their names; then the man had disappeared, and it was hard to track him down. As Edison told the story long years afterward, the lawyer had been driven to commit these frauds because he was in desperate money straits, owing to the serious illness of his wife; and so Edison had done nothing about the matter. With equal innocence of heart he gave his trust entirely to Gilliland, the kind friend through whom he had first met Mina Miller and whose charming wife was Mrs. Edison’s closest friend.

The new phonograph had come of age, in its inventor’s view; it was to create a large new industry. Hence he hoped to receive in return for exclusive patent rights something like a million dollars at the least. But Gilliland and Tomlinson, after repeated conferences alone with the “angel,” reported that the best they could get from Lippincott was $500,000, as well as a contract for Edison to manufacture the machines exclusively for the new company. For ten days the inventor, somewhat disappointed, considered the matter. In the end he did as they urged.513

And what of Gilliland’s agreement with Edison for an exclusive selling agency? Gilliland and Tomlinson said that they had arranged to assign this contract also to Lippincott in return for a payment of “only $50,000.”

The thought evidently passed through Edison’s mind that his devoted friend and personal attorney were making a pretty good thing out of his phonograph invention. But more than one of his close associates, like Johnson, had become passing rich through working with him; and he had no objection to that. The contracts between Edison and Lippincott were drawn up by Tomlinson and signed that summer, while a separate contract for the American sales agency passed between Lippincott and Gilliland and Tomlinson, the actual terms of which Edison was not told about. Moreover, the two men asked Lippincott not to reveal them to Edison for fear that he would think they were getting too much.514

Final arrangements, and payments of securities and cash, were completed on August 31, 1888. The next day Gilliland and Tomlinson were to leave for Europe (with their families) to negotiate the sale of Edison’s phonograph patent rights in Europe. Just before departing, Tomlinson brazenly appealed to Edison for cash with which to meet the expense of his journey, pretending that he had worked hard on the big Lippincott deal for but small fees. Edison kindly handed over $7,000 more. Thus, as it turned out, he had even paid for Tomlinson’s getaway. It was the last he ever saw of that precious pair.

Ten days later, Jesse Lippincott, the would-be founder of a phonograph trust, the North American Phonograph Company, had some second thoughts about his dealings with Gilliland and Tomlinson. He came to the Edison Laboratory and made a complete revelation of how both he and the inventor had been gulled. On the understanding that these trusted agents of Edison were covertly helping him, Lippincott, to buy the Edison phonograph patents cheaply, or at half of what the inventor thought they were worth, Lippincott had made a secret bargain by which he agreed to pay Gilliland the enormous commission of $250,000 in cash and securities for the Gilliland sales agency contract. That was half of what Edison himself was to receive; and yet Gilliland had never put a penny into the enterprise and had never sold anything as yet. Moreover, the lawyer, Tomlinson, had made a bargain with Gilliland by which he was to receive a third of the other swindler’s share.515

When Edison learned of all this, he was heartsick; he realized he had been deceived and betrayed by his friend Gilliland and by his own personal attorney. As he said at the time, it was his custom to trust his intimate associates, and this habit of his was well known. When the affair was reported in the newspapers, a while later, it was rather widely remarked that the inventor “had no pretensions to business sagacity.”516 But Lippincott was no wiser. It was only after thinking over the matter that he decided the two men had acted in fraudulent fashion, and thought that he might somehow avoid paying them the rest of the large sums he had promised them by making a clean breast of his secret dealings. His own hands, however, were scarcely clean.

The lawyer in the case, by acting as attorney for both sides of a contract and deceiving Edison, his original client, had behaved in so unethical a manner that it could have led to his disbarment. His connection with the Edison companies would be terminated, his reputation would be ruined. As for Gilliland, Edison sent him a cablegram:

I have just learned that you have made a certain trade with Lippincott of a nature known to me. I have this day abrogated your contract and notified Mr. Lippincott of the fact and that he pay any further sum at his own risk. Since you have been so underhanded I shall demand refunding of all money paid you and I do not desire you to exhibit phonographs in Europe.517

Usually Edison laughed off his heaviest reverses, but this time, as his wife and eldest daughter Marion perceived, he was deeply wounded. He had truly cared for Gilliland as a friend; now, he said, he “would never trust anyone again.” In his later years he had many close business and scientific associates and old retainers whom he was evidently fond of, but he allowed himself no intimate friendships — save that with Henry Ford, the Croesus of the automobile world.

When Gilliland and Tomlinson refused to consider repaying any part of the money, suit was instituted against them, in January, 1889, and the wretched affair became public, much to Edison’s regret. The defendants were able to show, however, that they had full authorization to act as Edison’s agents and that a breach of ethics, rather than provable fraud, was involved. A demurrer was entered by their attorneys, and litigation was dropped by Edison’s lawyers.518 It was, after all, only a minor scandal in a period notorious for business corruption on a large scale.

Wealth sometimes dripped from the great inventor’s hands into those of men with superior cunning. At any rate, Edison’s phonograph was reborn after ten years; with its clear, if thin, voice, it created renewed wonder and amusement for the public of the gay nineties. Being under contract to supply Lippincott’s North American Phonograph Company with many thousands of phonographs, Edison erected a large factory for this purpose adjacent to his laboratory at West Orange and employed hundreds of workers. Soon afterward he engaged more factory space in a nearby town for the production of wooden phonograph cabinets. Within a few years the well-loved phonograph was the source of employment for many thousands of workers, in Edison’s and in other plants. Its rapid growth as a large new industry, however, was attended with an incredible amount of business and legal trouble.

The inept Lippincott, who headed the abortive talking-machine trust in its early years, soon showed himself wanting both in commercial sense and in vision. Edison had contemplated selling phonographs outright at $85 to $100 apiece; Lippincott, in imitation of the successful Bell Telephone Company, followed the plan of issuing licenses to local dealers in cities and territories and, through them, renting the machines at $40 to $60 a year. The results, however, were extremely disappointing.519

The early business phonographs, moreover, with their two diaphragms for recording and reproducing, often broke down; their stylus points grew dull, and their motors proved balky and had to be replaced, after several years, with clock springs. The short, two-minute cylinder records had a capacity for only about four hundred words, which was inconvenient. To stop the machines for correction was well-nigh impossible. Stenographers in those days were usually male, and they tried to boycott the phonograph, as a machine that threatened their livelihood.

Although there was a growing interest and trade in phonographs, Lippincott seems to have managed things at the distributing end so poorly that Edison formed a very low opinion of him. On the occasion of some difference between them, he addressed a sharp note to Lippincott saying, “I shall send a civil engineer with a theodolite to see if your head is really level.”520

With but few exceptions local distributors who had taken up licenses to sell the phonograph as a business machine soon went out of business. One of the exceptions was the Columbia Phonograph Company of Washington, D.C., which began by providing a good repair service and sold many instruments to government bureaus. In addition to that, this company, the forerunner of the present-day Columbia Broadcasting Company, was among the first to undertake the sale of duplicated music records for entertainment purposes.

The great success of the phonograph was to be not as a business machine but in the entertainment field, when, toward 1892, it was introduced into popular nickelodeons as a coin-in-the-slot machine, grinding out light music and comic dialogues for the multitudes. The brass bands, the music-hall tenors, and sopranos resounding in thousands of the tinny 1888 models offered nothing to be admired as art, but at all events they pointed the way to the future, to the rightful role of the phonograph as purveyor of music to the masses.

After a while the unfortunate Lippincott found himself unable to meet his business obligations, and at the same time became seriously ill, suffering a stroke of paralysis. His largest creditor was Edison, to whom he owed money for thousands of phonographs that had been delivered and not paid for — these debts, however, being secured by collateral, the controlling stock of the North American Phonograph Company. By the autumn of 1893, a time of profound business depression, Edison, as both principal creditor and largest stockholder of the tottering North American Phonograph Company, was its de facto head. While working constantly at the technical improvement of his machine, he also shaped plans to rebuild the whole enterprise. To this end he had a survey made of the whole phonograph trade, which showed its condition to be perfectly chaotic. While some local firms, the Columbia company especially, had already built up a mass market in duplicated popular music records, North American itself had never produced a single record that was fit to sell.521

During the 1890s rival inventors also appeared on the scene, a short time before Edison’s basic patent was due to expire; the most skillful of these was Emile Berliner, who had developed the flat-disk record, and a stylus making a lateral cut, instead of the vertical or “hill-and-dale” cut of the Edison and the Bell-Tainter instruments. Berliner’s machine, known as the “gramophone” in England, was the ancestor of the Victor Talking Machine, whose trade-mark was the faithful little terrier listening to “his master’s voice.”

Edison’s new plans, as they matured, called for the development of a simplified phonograph at a popular price, designed primarily for musical entertainment. He also contemplated making and selling popular music records. But before launching such a program he decided to put the North American Phonograph Company into friendly receivership, so that he could take back full rights in his invention. When he did this, in 1894, he was obliged to take on the liabilities of Lippincott’s ruined phonograph “empire” and thus was involved in suits of various kinds directed at Lippincott’s company, during which, by court order, he was prohibited from selling phonographs in the United States for a period of about three years. (His growing export sales, however, were unaffected.)

Henceforth, he resolved to keep the phonograph business in his own hands. When the unhappy interlude of the North American Company’s receivership ended, he would reenter the field with an instrument whose sound recording was vastly superior to the second model’s, and one that was remarkably cheap as well.

4

In pursuing the story of the phonograph and bringing it to a convenient stopping place we have, perforce, run ahead of important inventive work by Edison going on simultaneously in other fields. It is breath-taking even to attempt to follow him as he moves restlessly from one type of investigation to others wholly different. In 1888, for example, one would find him patenting a new incandescent lamp, in which the carbonized bamboo filament is replaced with “squirted” cellulose, making it both more efficient and more economical. At the next moment we find him at work on a revolutionary type of mining machinery. Then there is a secret dark room, upstairs in the laboratory building, where only two chosen assistants are permitted to work with the master. Doubtless there are fabulous goings-on in that room, which none as yet will disclose. Thus, even in what is for him a relatively unproductive period, full of business headaches, the Edison Laboratory at West Orange fairly boils with its varied activities.

A group of scientists arriving to visit him in the spring of 1889 find him, to their alarm, with head and face swathed in bandages. It is nothing serious, he explains; simply that a crucible happened to explode while he stood close by. The press reported the affair under the headline:

EDISON BURNED BUT BUSY522

In the winter and spring of 1889 he had felt more tired than ever. His young wife, attempting to minister to his health, tried for a long time to persuade him to rest. Then at last, to her great delight, he agreed to take a long holiday, and in fact to go to Europe with her.

The vacation trip turned into a triumphal tour. They sailed on the French liner La Bourgogne on August 3, 1889, their first destination being Paris. Putting the Gillilands and Lippincotts and all the growing pains of the electrical industry as well, out of his mind, Edison once more was as carefree as a boy. He was to visit the great Universal Exposition in France, see the new Eiffel Tower and all the contrivances of the nineteenth-century inventors, including his own electrical, telegraph, telephone, and phonograph inventions.

Nothing could have made Mina Edison happier, after the years of relative seclusion in her country house. She was a young matron of only twenty-two, in her full beauty, and she loved to shine in society. In Paris she would share in all the public honors that the world nowadays lavished on her husband wherever he made his appearance. On their very arrival at the dock in Le Havre an official delegation representing the French Republic was on hand to meet them; reporters from newspapers of many European countries were there to interview them, and crowds cheered them on their way to the train. In Paris there were more and bigger crowds, and more government dignitaries to bid them welcome.

A crew of Edison men, headed by William J. Hammer, had arrived several months earlier to prepare a display of Edison products that would cover a whole acre of the Fair grounds. Here a complete central lighting station had been erected, and was surmounted by one of Hammer’s brilliant electric signs, made up of colored bulbs representing the flags of both France and the United States. There were also “fountains of light.” Indeed, the Edison system provided a thrilling picture of the world’s future illumination. But the longest lines of people, an estimated 30,000, were drawn to the new phonographs, which ranked only second to the Eiffel Tower as an attraction.

The fêtes for Edison seemed unending and often wearied him, though he observed that his wife apparently could never have her fill of them. Shortly after his arrival, King Humbert of Italy named him a Grand Officer of the Crown of Italy, and sent him impressive decorations at the same time, thus, as the newspapers said, “making Mr. Edison a Count and his wife a Countess.”523 The next day the inventor and his wife were received at the Elysée Palace by President Sadi Carnot, who, in a formal ceremony, decorated Edison with a red sash and named him a Commander of the French Legion of Honor. At a banquet given him by the City of Paris, and at another by the newspaper Figaro, the official speakers paid homage to him as “the man who tamed the lightning.” “Edison est un roi de la république intellectuelle; l’humanité entière lui est reconnaissante!” it was said.

Well he might be a “king of the intellectual republic” to whom the entire world was indebted; and presidents, (Bonapartist) dukes and duchesses, and even Oriental sultans might do him honor; but Edison could neither hear nor understand what they were all saying.

“Dinners, dinners, dinners,” he said in recollection, “but in spite of them all they did not get me to speak.” Refusing to speak in public, he had the American Ambassador, Whitelaw Reid, reply for him when a retort courteous was in order.

During the ten days in Paris the American inventor, with his big head, expressive features, and youthful bearing, became familiar to the people in the streets, who besieged the entrance of his hotel in the Place Vendôme to see him — among them being many would-be inventors, desperately anxious to consult him on their own discoveries. No American in civil life, saving perhaps Buffalo Bill, of the Wild West Show (then playing in Paris), was more renowned in Europe.

At the Opera House, as he entered a box — the guest of the President of the Republic — the orchestra played “The Star-Spangled Banner,” while the audience cheered and called on him to speak. He seemed overcome with emotion, merely rose to his feet, bowed, and sat down.524

After I had been there an hour [Edison relates] the manager came around and asked me to go underneath the stage, as they were putting on a ballet of 300 girls, the finest ballet in Europe. It seems there is a little hole on the stage with a hood over it, in which the prompter sits... I was given the position in the prompter’s seat and saw the whole ballet at close range.525

Marion Edison, who had been studying at Geneva in the charge of a friend of Mrs. Edison, joined her parents in Paris. She recalls that her father disliked the crowds and social life, but that her stepmother insisted that he come out with her to meet all the distinguished people who wanted to see him. “Oh they make me sick to my stomach!” he would exclaim on returning from those long dinners.

It was plain to see that the youthful Mrs. Edison and her high-spirited stepdaughter of seventeen agreed in “everything save their opinions.” It is not unusual for a young wife to find difficulty in asserting her authority over the grown-up children of a middle-aged widower, and, at that, children who have been reared in a way quite different from her own upbringing. Marion was clearly “jealous” of the beautiful young woman who had taken not only her mother’s place, but as she may have felt, her own place as well in her father’s affections. But, then, Edison himself used to indulge in little pleasantries about his wife’s taste for “socials” and for pomp and circumstance. For example, he would refuse to appear in public wearing his impressive decorations, such as the red sash of the Legion of Honor, saying, “I could not stand for that... My wife had me wear the little red button, but when I saw Americans coming, I would slip it out of my lapel, as I thought they would jolly me for wearing it.”526

More agreeable to him was his visit to the Eiffel Tower, and the luncheon high in the sky, of which he partook as the guest of the famous engineer, Alexandre Gustave Eiffel, who had designed the great tower. Then Buffalo Bill, Colonel William F. Cody himself, was in Paris with his Wild West Show encamped in its outskirts, which, as a popular attraction, rivaled the Exposition itself. Edison could think of no finer diversion than to go there, eat an American “grubstake” breakfast of pork and beans with the famous Indian scout, and ride at top speed in a “Deadwood coach” around the enclosure, together with Senator Chauncey M. Depew and other dignitaries, while a “savage horde of howling redskins” pursued them fiercely and poured volleys of blank shot at them.527

In more serious mood, Edison dutifully toured the Louvre with his wife and saw its old treasures, which he did not enjoy. Though he possessed a great imagination in practicing his own mechanical arts, he said, “To my mind the Old Masters are not art, their value is in their scarcity and in the vanity of men with lots of money.” On the other hand he did enjoy the painters of the nineteenth century and the great Impressionists whose works were then consigned to the Luxembourg Palace.

A noteworthy event was his visit, at the invitation of Louis Pasteur, to the famous Pasteur Institute. Edison’s own notes show that he deeply respected the inspiring French scientist and considered his “germ” theory to be one of the greatest discoveries of all time. He had a good talk with Pasteur, then watched how he inoculated crowds of persons, hour after hour, with his marvelous vaccine. There was hidden drama here too; for example, a handsome boy was brought to him too late, after being infected with hydrophobia. “He will be dead in six days,” Pasteur whispered to Edison, after the boy had been duly inoculated and had left.

How different, how contrasting were the careers of these two men: Pasteur, preeminently the scientific discoverer; Edison “the most famous inventor of his time.” To be sure, certain discoveries of Pasteur were of immense commercial benefit to all agriculture and to the production of wine. A good many years before, in 1865, Napoleon III, in the course of an audience with the scientist, had expressed surprise that Pasteur had never used any of his discoveries as a source of commercial profit. Pasteur had replied that a true scientist would consider he “lowered himself by doing so.” To make money by his discoveries, “a man of pure science would complicate his life and risk paralyzing his inventive faculties...”528 Pasteur, in fact, deeply enjoyed seeing the immediate, practical effect of his ideas on men and things, but nothing must be permitted to draw him away from experimentation.

From Paris the Edison party went on to Berlin, and the inventor met Hermann von Helmholtz, one of the greatest and most imaginative physical scientists of his century. Like Pasteur, Helmholtz showed esteem for Edison because his resourcefulness in applied science opened new avenues to scientific knowledge itself. But there could not have been much meeting of minds with Helmholtz, who, in any case, spoke no English. With the foremost German electrical inventor Werner von Siemens, who did understand English, communication was more possible, and more worldly. Together they traveled from Berlin to Heidelberg, in a private railway compartment, to attend a scientific convention there, Edison regaling Siemens all the while with his fund of American stories.

Late in September he arrived in London, which he had last visited in 1872 as an obscure young inventor of telegraph devices. Now the tycoons of the electrical industry were most eager to talk with him and entertain him in their big country houses. In London he had occasion to inspect the Edison central station at Holborn Viaduct, which was run with direct-current generators, at 110 volts. But the dawn of alternating-current usage had come; Gaulard and Gibbs converters had already been invented several years earlier, opening the way to the distribution of more powerful currents. Edison also met S. Z. Ferranti, who was just then building a gigantic a-c dynamo designed to send currents of ten to fifteen thousand volts over long distances into the central district of London for electric lighting. The Edison d-c power station had a radius of only a mile and a half at most. On being asked for his opinion of these innovations, Edison declared that he deemed direct current the only safe medium for distribution of power, and held Ferranti’s ideas to be “too ambitious.” Nevertheless heavy current engineering was now advancing with great rapidity — though the man who had done so much, by his practical work, to stimulate progress in electrodynamics would have no part in it.

On the return voyage, Edison was thoroughly relaxed, having traveled and loafed for two months on end. He was a good sailor, and his humor was as unfailing and “aggressive” as usual. During the Channel crossing to England, a rough passage, when his family and all the passengers became ill and were forced to go below deck, he stationed himself in the saloon and there enjoyed one of his foul cigars. Whenever any of the wretched passengers came up for air, Edison, as he admitted, deliberately “would give a big puff and they would go away and begin again.”

Immediately on his arrival in New York (October 6, 1889) he hurriedly crossed the harbor in a launch to the Jersey shore, then rode by carriage to the laboratory at West Orange. He was burning to know the results of certain secret experiments that had been going on during his absence behind the locked door of Room 5. But Batchelor and W. K. L. Dickson had meanwhile put up a small new building in the laboratory “compound” for these new purposes. Proudly Dickson showed his chief into the “studio” and prepared to demonstrate what had been accomplished, in accordance with Edison’s instructions, during his stay in Europe.

Edison sat down; the big room was darkened; Dickson went to a bulky apparatus at the back of the room that resembled a large optical lantern. Next to it, and attached to it, was a phonograph. Against the wall, facing Edison, there was a projection screen. Dickson turned a crank, and a vague flickering image of Dickson himself “stepped out on the screen, raised his hat and smiled, while uttering the words of greeting: ‘Good morning, Mr. Edison, glad to see you back. I hope you are satisfied with the Kineto-phonograph.’”529

So Dickson wrote in 1894, not long after the event. The development of the first operable motion picture camera — invented but not yet patented by Edison, and hence unknown to the world — was well under way. Connected with it, though rather rudely synchronized, was a model of his improved phonograph. Thus the first motion pictures were not silent, but were talking pictures.