1 ~ The Edisons

1

The village of Milan, Ohio, where Thomas A. Edison was born, with its old tree-shaded central square and its quiet lanes of white wooden frame houses, now seems to us a rural backwater, a relic of early nineteenth-century America. The main arteries of Ohio’s teeming traffic along the lake shore, like the railway, pass it by. Nonetheless, Milan in its heyday was one of the boom towns of the Middle West and stood for a time almost at the center of America’s westward-flowing population. For over twenty years a flood of “internal immigrants” from the East Coast, mainly Yankees, but also recent arrivals from Europe, had been moving up the Erie Canal and along the lake to settle on the virgin soil of the Western Reserve. This region quickly became one of the great granaries of the world. Its little lake ports, which had been villages a decade or two before, such as Toledo and Cleveland, were turned into veritable cities. With loud hammering and sawing the people of “New Connecticut” were putting up homes, shops, and even small factories, especially near the water sites. There was town-booming and canal-digging on every hand — for the canal was the favored medium of transport to the sites of navigable rivers and lakes. The new towns that were laid out by the migrant Yankees, with their white, belfried churches and green commons, and names such as Norwalk and Westport, were of distinctly New England appearance. Such was Milan, a frontier hamlet of a few cottages in the 1820s, but a thriving community of three thousand souls a decade or so later, where a man of energy might well grow up with the country.

Here Edison’s father, Samuel Ogden Edison, Jr., a native of Canada, had halted in the course of a season of wandering, in the summer of 1838, and decided to put down his stakes. Like a good many of his fellow immigrants he had left his troubles behind him, at home, and had journeyed to thriving Ohio in the hope of bettering his fortune.

Milan was situated on the Huron River, eight miles inland from Lake Erie; but the founding fathers had wisely exerted themselves to build a canal, forty feet in width, extending northward three miles to the navigable part of the river, and so giving access to Lake Erie’s broad waterway. At the time when Samuel Edison, Jr., came to Milan, construction work on the Huron Canal and its basin was going on full blast. Looking at the busy scene, Sam Edison, a man of enterprise himself, blessed with the commercial optimism of Mark Twain’s Beriah Sellers — hero of The Gilded Age — saw in imagination, not mountains of copper or coal, but certainly the shape of the growing local industries of the future, out of which he might turn many an honest penny. He saw Milan transformed almost overnight, once the canal was finished, into a strategic port on America’s inland sea. He saw long trains of oxcarts, laden with wheat, pork and wool, converging down all the dirt roads of the neighboring counties upon the new Huron Canal Basin, whence ships and barges of over one thousand tons’ capacity would carry freight to the lake, for transhipment via the Erie Canal across the Atlantic. What was more, he saw that warehouses and grain elevators would be needed at the canal terminal. Having had some experience of the lumbering trade, he resolved to take up the business of supplying timber and roofing material for the greater Milan that was to come.

Sam Edison had departed from Canada rather suddenly, about six months earlier, after having been involved in the political disorders of 1837. He was then still in his early thirties. Unhappily, he had been forced to leave his wife and four young children behind him in Ontario Province until he could establish himself in the States. With the help of his family he was able to raise a little money and for seven or eight months he worked zealously to set up his shingle mill. Some help was given him also by an American friend, Captain Alva Bradley (a future merchant prince), whose ships and barges plied Lake Erie between the Ohio lake towns, such as Milan, and Port Burwell, on the Canadian side, a few miles from the former home of Sam Edison. Bradley arranged for the shipment of Canadian lumber of good grade to be cut into shingles at Sam Edison’s mill.

By the spring of 1839 Edison had hired a few men and was ready for business. Now at last he was able to bring his wife and children across the lake on one of Bradley’s barges. After living in temporary quarters for about a year, the Edisons purchased, for the sum of $220, a town lot of an acre on Choate Lane, situated at the edge of the “hogback,” or bluff, about sixty feet in elevation, that overlooked the Huron Canal Basin where the shingle mill stood. Here, in 1841, Sam Edison, with his own hands built a tidy house of wood-frame and brick construction, using lumber from his own mill. It was to be the Edisons’ home for many years.

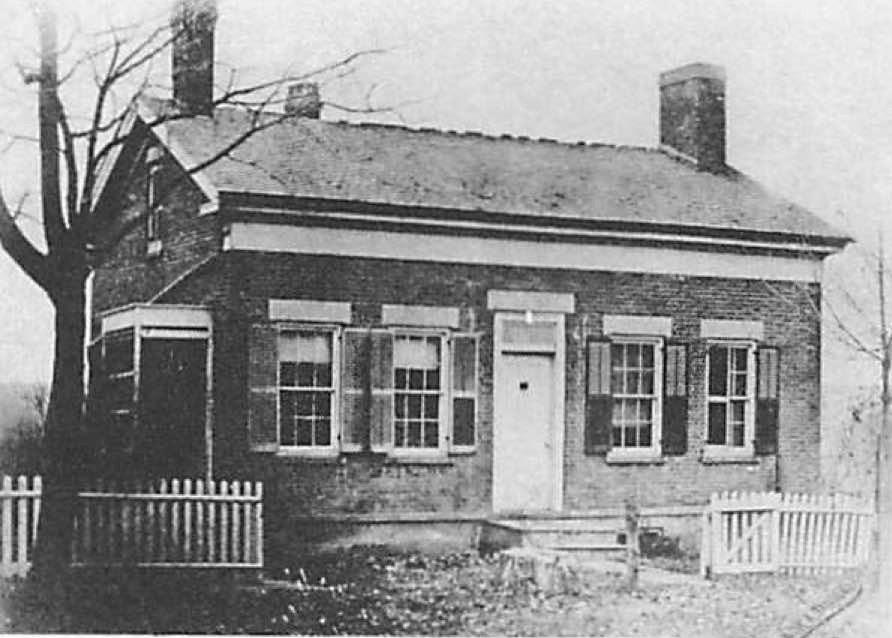

The house, built into the side of the bluff, still stands; it has the simple but pleasing lines of the Greek Revival dwellings of the first half of the nineteenth century. Made up of seven small rooms, its living room is at street level, the bedrooms are in the attic, while the large kitchen and pantry are set below the hill, at cellar level, but open on the sloping orchard behind the house and the view over the canal basin, once the busy scene of sailing ships and barges riding in and out of the roadstead across the flat, green prairie. It is a solidly built and comfortable dwelling, the home of a tradesman who enjoyed some seasons of good fortune.

2

Although Sam Edison was a Canadian by birth, his family had originally settled, more than a hundred years before, in what was then the Crown Colony of New Jersey. After the War of Independence was over, the Edisons, being stanch Loyalists, indeed most obstinate in their devotion to the King, were driven as exiles to Canada.

They were a hardy and restless clan, part Dutch, part English. As a family group they seemed disposed to boldness rather than to prudence; and, far from avoiding trouble or danger, they fairly courted it. Thus they endured periodic misfortunes and were uprooted more often than were most families in those times.

John Edison, the original of the Edison line in this country, according to family tradition was the descendant of peasants and millers living by the Zuyder Zee in the Netherlands. No direct connection, however, with Edisons, or Edesons, in Holland has ever been traced. Such incomplete records as we have show that a Netherlands widow named Edison arrived at Elizabethport, New Jersey, in 1730 with an only child of three named John, and that the widow, “who never married again, deceased and left her valuable estate to her son.” These facts come to us from the annals of the well-known Ogden family, of New Jersey, with which John became connected in 1765, upon his marriage with Sarah, daughter of Samuel Ogden.1 Thereupon he became the proprietor of a farm of seventy-five acres in the township of Caldwell, Essex County, New Jersey, and was possessed of a house, a Negro slave, one black mare worth twenty pounds, fifteen sheep, and other goods and chattels valued by him at a total of 288 pounds sterling.2 John Edison, almost a patroon in those days, might have prospered in the Passaic Valley; but the insurrection against the British monarch was spreading in America and by 1776 had reached the phase of open warfare.

In New Jersey the division of popular sentiment about the Revolution was extremely close, a large minority remaining loyal to the King. The Loyalists were usually people of property, such as the Ogdens and their relative John Edison, though such families were also often divided in their allegiance. On October 20, 1776, at a period when the Whigs, as the local patriots were called, had taken over in Essex County and were burning the barns and driving off the cattle of their Loyalist neighbors, the Tory John Edison, together with his family and several of the Ogdens, took flight across the Hudson River and found refuge in New York, which was within the King’s lines. But when Washington’s beaten troops retreated soon afterward southward through New Jersey, the British and Hessian forces followed them, and John Edison came back.

It would have been well if he had remained passive in this civil struggle, for John Edison was of middle age and burdened with a numerous family. But he was stanch in his monarchical principles; he took up arms and joined the forces of General Howe as a scout, to help the British deal with the Continental guerrillas in the wooded ridges of New Jersey. During the confused skirmishing between the two forces in 1777 — after Washington’s army had rallied at Trenton and moved up again — John Edison, with his brother-in-law Isaac Ogden and three other Loyalist fighters, fell into the hands of the revolutionary militia and was imprisoned in the wretched Morristown jail for more than a year.

John Edison might have won his freedom by taking the oath of allegiance to the Continental Congress. This, however, he and Ogden refused to do. In January, 1778, they were tried by New Jersey’s Council of Safety on the charge of high treason, convicted, and sentenced to be hanged, though execution, fortunately, was delayed.3

Meanwhile, Sarah Edison in New York moved heaven and earth to win the release of her husband and brother. Through the influence of members of her family who served in the Continental Army — among them her own father — the lives of John Edison and Isaac Ogden were spared. Later in 1778 they were paroled and sent back through the British lines to New York.

The successful outcome of the Revolution was a complete disaster for the Edisons. After having flourished in New Jersey for many years, they saw all their property confiscated and were forced to sail from New York Harbor in 1783 as émigrés in the gloomy British fleet that transported 35,000 American Loyalists to the West Indies and to Canada.

Many of the United Empire Loyalists who could prove they had suffered loss of property because of their devotion to His Majesty’s Government during the late war were given grants of land to aid their resettlement. After several months of painful delay, the Edisons were awarded some lots in the Hatfield Grant in Nova Scotia, a strip of bleak wilderness adjoining Digby, on the east coast of the Bay of Fundy. Here for a quarter of a century they strove against the inhospitable forest and marshland; marriages, childbirths, and deaths followed in succession. But they were a virile race. The numerous sons and grandsons of Tory John, bearing names like Samuel, David, Moses, and Isaac, were very tall and sinewy men with pale blue eyes and big noses. The eldest son, Samuel Ogden, was married in 1792 to Nancy Stimpson of Digby; eight children came to them, the sixth, who was born in August, 1804, being named Samuel Ogden, Jr. Even the aged patriarch of the clan had more children; and soon there was a tribe of nineteen Edisons, counting grandchildren and daughters-in-law, and scarcely enough land to sustain them. After twenty-eight years, the family decided to give up the struggle in fogbound Nova Scotia and move on to some new frontier.

Upper Canada now clamored for pioneers; as in the United States, a stream of immigrants moved westward along the Great Lakes, to clear the forests of what is now Ontario Province. The Edisons received an award of a section of six hundred acres of pineland along the Otter River, about two miles inland from Lake Erie. In the spring of 1811 they were all on the move, old and young; proceeding by ship to New York, they continued overland by ox team and wagon for eight hundred miles, the journey lasting all summer. On arriving at their new homesite, a point in the wilderness twenty-one miles from their nearest white neighbor, the sturdy Edison men set to work at once cutting down trees and hewing logs, throwing up cabins, and uprooting stumps, as they had done in the Nova Scotia forest a generation before. The Indians here were friendly; the woods abounded with game; the Edison women preserved and stored food, and made divers preparations against the coming of winter.

The much-traveled Edisons had just dug themselves in at their “settlement” when, on a January night in 1812, a runner came over the snow from St. Thomas to give warning that war with the United States was at hand. Volunteers were called for; and Samuel, the eldest son, responded by offering to raise a company from among the recent arrivals in the region. Samuel Edison, Sr., fully shared his father’s feelings of loyalty to the Empire. As captain of a company of the First Middlesex Regiment under Colonel Thomas Talbot, he acquitted himself well in the strange war that was waged on the lakes and in the forest — which saw Detroit quickly surrendered to the British-Canadian forces. After that victory, in November, 1812, Captain Samuel Edison and his volunteers were released from service so that they might go home to provide for their families in the deep Ontario woods.

With the coming of peace, immigration along the lakes was greatly swelled; in the 1820s the “Edison settlement” became a village, named, oddly enough, Vienna. It boasted a main street, a schoolhouse, a Baptist church, a cemetery — for which the Edison family donated land — and even a tavern, in fact all the amenities of rural civilization.

While the forests were being cut down the region flourished, pine logs in quantity being floated downstream to nearby Port Burwell for shipment to England. The numerous sons of the local war hero worked at the lumbering and carpentry trade as well as on the farm. Captain Edison’s own means improved enough to permit him to build a neat clapboard house overlooking the Otter River and having real glass windows and iron nails. In their neighborhood the Edisons were known as hospitable folk whose latchkey was always left hanging out when they were away, so that strangers passing by might enter and take food or shelter.

A simple, hardy, pioneering people, the Edisons labored all their lives in the forests and the fields. Most of them were short on education — John Edison could not sign his name correctly; his grandson Samuel Edison, Jr., could scarcely spell enough to write out a bill. Yet among these people you would find dissidents, an occasional eccentric, even one or two who railed at religion. A marked family trait distinguished them; they were strong individualists, often nay-sayers, and independent-minded to the point of obstinacy — a quality less uncommon in the earlier America than now. The provincial annals of Canada show them to have been long-lived and prolific, “humble tillers of the soil, toiling in contented obscurity.” Few traces of them would have remained if the world’s attention had not been drawn one day to one illustrious descendant.4

3

Even in their frontier village in Upper Canada there was scarcely enough land to provide for all the Edison clan, so numerous were their progeny. John, the old Tory, had finally died in 1814, at almost ninety. Captain Samuel lived on to the ripe old age of ninety-eight, much esteemed by his neighbors — though he was also known at times to have been a very crusty, stubborn, and even rancorous fellow. In 1819, for example, he and his wife Nancy decided to be baptized into the Baptist Church of Port Burwell. But neither proved to be tractable members of their congregation. The church records reveal that “after the steps of labor had been taken with the captain, according to the word of God,” the congregation voted that he should be expelled “for railing and refusing to obey the voice of the church.” Soon afterward similar punishment was visited upon Nancy Stimpson Edison for nonattendance.5

When he was almost sixty, Captain Samuel, the diverting old sinner, finding himself widowed and the father of eight full-grown children, married again and sired five more. The sight of him, with his big head and snowy beard, made a profound impression upon his American grandchild Thomas A. Edison, who in 1852 accompanied his parents on a visit to the old Ontario homestead.

We crossed [Lake Erie] by a canal boat in a tow of several others to Port Burwell, Canada, and from there we drove to Vienna. I remember my grandfather perfectly as he appeared at 102 years of age when he died. In the middle of the day he sat under a large tree in front of the house facing a well-traveled road. His head was covered completely with a large quantity of white hair, and he chewed tobacco incessantly, nodding to friends as they passed by. He used a very large cane, and walked from the chair to the house, resenting any assistance. I viewed him from a distance and could never get close to him. I remember some large pipes, and especially some molasses jugs that came from Holland.6

When the Captain remarried in 1825, his sixth-born, Samuel Edison, Jr., who was to be the father of Thomas A. Edison, was twenty-one. Born in Nova Scotia, as a small boy he had made the long trek to Upper Canada with his parents; now he stood six feet and one inch tall, was very sinewy and strong, and could outrun and outjump any man in Bayham Township. Through restlessness or ambition, he had been led to try several different trades — carpenter, tailor, and lately tavernkeeper. Moreover, he was much concerned with the troublous politics of the time; indeed, his tavern in Vienna was a gathering place of the local agitators for reform. Samuel junior, something of a hothead, ventured to differ in his opinions with his Tory father and was no less stubborn in upholding them. Like the young men of Boston and Philadelphia fifty years earlier, those of Upper Canada were now loud in talk over their ale about the want of representative government and their resentments against the King’s ministers.

Meanwhile, a small, round-visaged young woman of seventeen, named Nancy Elliott, then serving as a teacher in the recently established, two-room school of Vienna, turned Samuel junior’s mind to thoughts of marriage. She was the daughter of the Reverend John Elliott, who had recently come to preach in the Baptist Church, and granddaughter of Captain Ebenezer Elliott of Stonington, Connecticut, a veteran of the Continental Army. There were Rhode Island Quakers also in the Elliott line. After the Revolutionary War the Elliotts had moved from Connecticut to western New York, and thence to Canada. Nancy’s two brothers were then studying to become Baptist ministers like their father. The Elliotts were not rich but they were godly and above average in education. Of course, many well-educated young ladies taught in rural schools in the 1820s for a pittance of five dollars a month, or even without pay, so that they might escape the drudgery of a farmhouse kitchen.

The young innkeeper soon went courting Miss Elliott; he was accepted, and in 1828 they were married and he took her home to a new house he had built with his own hands. Four children were born to them in Vienna in the early years of their marriage: a daughter, Marion, in 1829; a son, named William Pitt, in 1832; a second daughter, Harriet Ann, in 1833; and again a son called Carlile, in 1836.

These were again troubled times. An insurrection, aimed at nothing less than the overthrow of the Royal Canadian Government, was being plotted in Upper Canada, none too secretly, by William Lyon Mackenzie. Through the backwoods the followers of Mackenzie journeyed, exhorting the settlers to join them. As early as 1832 the younger Sam Edison was publicly denounced as a leading figure among the would-be revolutionists by his father’s former commander, Colonel Talbot, who characterized him as “a tall stripling, son of a United Empire Loyalist, whom they [the insurgents] transformed into a flagstaff.” The authorities had evidently learned that the young Edison sometimes drilled armed bands of his Vienna neighbors in the woods after dark.

In December, 1837, Mackenzie, at the head of a few hundred rebels in Toronto, made his desperate bid for power — which was timed with a similar rising in the French-speaking Provinces under Papineau. The insurrectionists, however, were quickly put to rout by regular soldiers, and Mackenzie was driven to flight across the Niagara River.

Sam Edison, Jr., with a file of Vienna and Port Burwell rebels, was marching on Toronto, through the deep woods, when news of the fiasco came to him. What was worse, a large force of six hundred militia was reported to be approaching to give him battle. Edison’s small contingent then dispersed through the woods, followed closely by the Government soldiers. Reaching Vienna, Sam paused at his home only long enough to bid good-by to his wife and children, then hid for the night in a barn near his father’s house. In after years, stories were told of how militia came to the old man’s house to search for the son; while the stern old Loyalist smoked his pipe and said nothing, his wife managed to delude the searchers.

Before dawn the younger Edison was off through the woods, running like a deer toward the United States border more than eighty miles away, hotly pursued by the King’s men with Indian guides and dogs. By performing the incredible feat of running for two and a half days, and stopping only for brief intervals of rest or food, this great athlete managed to reach and cross the frozen St. Clair River and find safety on the United States shore at Port Huron, Michigan.

When the father learned that his son had made good his escape, he was said to have remarked dryly, “Well, Sammy’s long legs saved him that time.”7

The disorders in Canada soon subsided when political reforms, especially home rule, were accorded by London. But Sam Edison, Jr., could not return, save under penalty of arrest and deportation to some penal colony. He had no alternative to seeking his livelihood in the United States. Thus the rebellious descendant of British Loyalists exiled from New Jersey in his turn was driven from Canada to the United States. Victims of revolution or civil disorder, the storm-tossed Edison family suffered exile twice in three generations. But Sam Edison, Jr., in effect had come around full circle and repatriated the family in its homeland. It was by this stroke of chance that Thomas A. Edison happened to be born in the heart of the American Republic.

4

After colonial Canada, Ohio seemed immensely “progressive” as well as enterprising. In this corner of the New World, as from the beginning of its settlement by white men, all was changing swiftly; the future meant everything, the past nothing. The country was still predominantly a wood-burning civilization; lake and river steamers and the first small railway locomotives consumed our forests. Farm crops, the stock in trade of eighty per cent of the people, still moved over fearful roads by oxcart. To us the tempo of life may seem languid. It was not so in the eyes of travelers from Europe observing the “restless” Americans under frontier or semi-frontier conditions.

America at the mid-century had become, in the words of Walt Whitman, “a nation of which the steam engine is no bad symbol.” Even in the small towns of the Middle West more and more people devoted themselves to the industrial arts, the great end in view being the establishment of home industries, and the manufacture of those articles of common use that formerly had been imported at high cost from Europe. There was too much to be done, and too few hands to do it. To a people in a pioneering society, so engaged, so absorbed, “every new method which leads by a shorter road to material comfort, every machine which spares labor and diminishes the cost of production... seems the grandest effort of the human intellect.”8

It was, after all, a very special kind of world in which the infant Edison would first see the light, one whose ruling idea (in Whitman’s words) was to be “all practical, worldly, money-making, materialistic,” yet holding the belief that such activity led always toward “amelioration and progress.” In such a society, elementary education at last would be free to all, or almost all, but the standards of learning would be low, and the opportunities for higher education few or poor. Seldom would the love of fine arts or purely scientific knowledge be handed down from father to son as in the communities of the Old World. Most young Americans, in fact, would grow up caring little for “the general laws of mechanics,” as Tocqueville observed, but thinking mainly of the “purely practical part of science.”9

On the other hand, a distinctive feature of America’s culture a century ago was that it offered a “most inventive environment.”10 Since their earliest days on this continent the American farmers and artisans possessed ingenuity and manual skill said to have been originally fostered by the harsh necessities of food-raising in the stony fields of New England.11 From subsistence farming the native of Massachusetts and Connecticut turned to a variety of household industries. He made good glassware, pottery, and utensils of copper and iron. The arts of shipbuilding and navigation, as later those of textile manufacture, gunsmithing, and clockmaking, were also advanced. The “whittling boy” on the farm, like John Fitch and Eli Whitney, grew up to be a jack-of-all-trades who thought constantly in terms of tools, machines, and practical appliances, free to ignore tradition and try new ways of doing things. Thus arose the great breed of Yankee inventors, our pioneers in applied science and technology, who, “though their means and knowledge were limited, and troubles beset them at every step... founded most of our important industries.”12 Invention, as the economic historian E. L. Bogart has said, became a “national habit.” According to a story sometimes attributed to Abraham Lincoln, the typical Yankee baby immediately after being born and placed in the cradle proceeded to examine the cradle to see if some “improvements” might not be worked out for it!

By 1851, the epoch-making inventions of the cotton gin and the sewing machine, the steamboat and the telegraph, among other exhibits of Americans at an industrial exposition held in London, were already winning for Yankee ingenuity the applause of old Europe.

The Yankee inventors, it must be remembered, joined in the movement of internal immigration, through the Erie Canal, toward the interior of the continent. Their skills were quickly disseminated among the pioneers of the Middle Western communities. European visitors were astonished to see how American artisans, such as Cyrus McCormick, inventor of the mechanical reaper, “revolutionized” agricultural tools which in Europe had remained unaltered virtually since the days of the Roman Empire.

Doubtless the English and European literary tourists who, like Dickens or Mrs. Trollope, were hardy enough to voyage to our frontier settlements around that time, counted on finding Americans living much as Rousseau’s “noble savages” were supposed to live: free and equal, but nonetheless barbarian. However, they were surprised to see that the American standard of life, even in the new communities, often included the use of many articles of convenience almost unknown to Europe. By the 1850s great numbers of American women had freed themselves from the slavery of needle and thread by acquiring Mr. Howe’s sewing machine; many also utilized new-fangled egg-beaters, apple-peelers and clothes-wringers astonishing to English travelers. Even in remote villages the people had a passion for rapid communication and intelligence, reading many newspapers that arrived by post, carrying on commerce by means of the newly invented electromagnetic telegraph.

The 1830s and 1840s marked the height of the Canal Craze in America. Before the coming-of-age of the Iron Horse, states and towns all but ruined themselves to finance the waterways that would give this continental nation a desperately needed transport system. Thus Milan boomed. Six hundred wagons a day arrived from points within a radius of 150 miles, enough to fill twenty big vessels and barges with 35,000 bushels of wheat each day. Soon fourteen grain warehouses lined the basin, most of them roofed with Sam Edison’s seasoned pine shingles. Milan was becoming known as the “Odessa” of America and was one of the nation’s busiest grain ports. For a period everything and everyone here seemed to prosper, including Sam Edison.

The family reunion in the United States was signalized by the arrival of more children. Nancy had brought four with her in coming to Ohio in 1839; Marion, the eldest daughter, then ten; William Pitt, eight; Harriet Ann, six; and Carlile, four. Now, in 1840, Samuel Ogden II followed, and four years later, Eliza. Unfortunately, the Lake Erie region is subject to severe winter storms; the Edison children suffered sorely from colds and from infantile diseases. Soon after being brought to Milan, in 1841, Carlile died at the age of six. Then soon afterward, to Nancy Edison’s great sorrow, the lately born Samuel II and Eliza were taken from her in their infancy. Within a few years half of her children were dead.

Nancy Elliott Edison, Thomas Edison’s mother. (All pictures, unless otherwise noted, courtesy Edison Laboratory National Monument.)

Nancy Edison, who was of Scotch-English and Yankee descent, was very different in character from the “Dutch” Edisons; she was small in size, but in her earlier years she showed much steadfast patience and inner strength against adversity. She appeals to us as having been more than usually intelligent and having absorbed from her own estimable family, the Elliotts, a love of learning as well as devotion to religion.

She was already middle-aged when, in the dead of winter, she awaited the birth of her seventh, and last-born, child. It was to be a son with fair hair, large blue eyes, and a round face, who strikingly resembled the mother but seemed unusually frail and perhaps, as the Edisons said, “defective.” His head was so abnormally large that the village doctor thought he might have brain fever. Nancy greatly feared for the life of this new child, who arrived in the world during the early hours of February 11, 1847, following a night of heavy snowfall. Later that morning Sam Edison, Jr., ran along the hogback to get medicine at the pharmacist’s in the village square, announcing to all his neighbors that a son had been born to him. The parents christened the boy Thomas, after a brother of the father, and added the middle name “Alva” in honor of their friend Captain Bradley. Thus, Thomas Alva Edison.

In this house in Milan, Ohio, built by his father, Thomas Edison was born, February 11, 1847.