19 ~ Motion pictures

1

At certain periods, after having been much away from his laboratory, Edison would say, “I am tired of industrial science,” and would promise to “rest himself” by taking up “pure science.”

Nature, he said, was often full of surprises, and it was fun to come upon them unexpectedly. In his laboratory notebooks there were observations of hundreds of curious, unexplained phenomena which would be most fascinating to investigate — especially things chemical and metallurgical.600

Though industrial science, that is, applied science, was really as the breath of his life, it was highly characteristic of our many-sided and restless inventor that he should allow himself sudden flights toward the unknown, the fantastic, or the “impossible.”

In 1890, a young writer named George Parsons Lathrop (son-in-law of Nathaniel Hawthorne), in preparing a biographical study of Edison for Harper’s Magazine, had been permitted to see some of the inventor’s notebooks and in his article had given hints of Edison’s ideas about future scientific discoveries. This was the heyday of Jules Verne’s scientific fictions. The literature of the age romanticized its inventors; and the inventors, in their turn, were inspired by the spirit of romance. Edison, for example, had read Jules Verne with enjoyment since the early 1880s. What was an invention but a romantic vision, up to the point where it was made practical?

Lathrop, at any rate, proposed to Edison that they collaborate in writing a novel having as its hero a scientist not unlike himself. Edison was to furnish the ideas for the inventions of future times, Lathrop the fictional intrigue, or plot. The title chosen for the work was “Progress”; and a publisher offered to promote it in newspaper-serial and book form. In the summer of 1890, Edison began to make notes and jottings on the imaginary scientific appliances of 1940-1950.

The manuscript notes for “Progress” consist of reveries or visions of things to come that fall within lines of direction already projected by contemporary scientific research. Edison prophesies a great advance in synthetic chemistry, biochemistry, and optics; artificial diamonds would become commodities of common use; the components of food, such as proteins, would be made by chemical processes; marvelous new plastic materials such as “artificial mother-of-pearl” would be contrived by chemical engineers and used to decorate the walls of palatial dwellings; all sorts of objects would be “plated” in some new and beautiful manner. (Could he have been dreaming of chromium plate?)

The future mode of transportation would be aerial navigation; and heavier-than-air vehicles would be developed to the point where journeys to Mars were entirely feasible. The spirit of “Progress” would also be introduced into warfare, which, in future times “would be conducted by dropping dynamite from balloons.”

Would man himself be improved? Edison, as a convinced Darwinian, anticipated a large advance in knowledge of eugenics, through experiments in the breeding and interbreeding of higher anthropoid apes. His hero-scientist founds a community on the upper Amazon in which, after eleven generations, the apes are made capable of conversing in English. “The 80th generation would equal in intelligence and personal beauty the Bushman tribe of Africa. (Lathrop you can enlarge on this yourself.)”601

Alas, these literary exercises were brusquely interrupted, and Edison was off to the Ogdensburg works to crush rocks again. To his despair, Lathrop was unable to persuade Edison to come down from his hills and continue with their scheme.

About five years later, in November, 1895, came the remarkable scientific discovery by Professor W. K. Roentgen, the German physicist, of the so-called X-rays emanating from a cathode tube; that their radiations could pass through the flesh and muscle tissue (though not the bones) of living animals and so make a shadow picture of them on a photographic plate aroused tremendous interest among the scientific public. The value of such an instrument for surgery was grasped at once; soon many investigators were at work devising fluorescent lamps and fluoroscopes, Edison one of the first among them.

Professor Michael Pupin, of Columbia University, engaged his interest by appealing to him at the time for help in discovering the most effective fluoroscopic chemicals. During a lull of activities at the ore mill, Edison went back to his laboratory and with his assistants tested crystals made out of about eight thousand different chemical combinations. Within a few weeks he sent the Columbia University scientist a fluoroscope with a tungstate-of-calcium screen — with which Pupin was enabled to make a clear shadowgraph of a man’s hand that was filled with shotgun pellets. Guided by the Edison fluoroscope a surgeon promptly performed the first X-ray operation in America, with complete success.

Pupin wrote Edison in acknowledgment:

Messrs Alysworth & Jackson sent me one of your fluoroscopes with your and their compliments. It is a beautiful instrument and it is of invaluable service in the new line of work opened up by Roentgen’s discovery. I took the liberty of showing its marvelous power at my public lectures; and the public enjoyed it more than anything else that I had to show; this is partly due to your great popularity... My experiments gave very encouraging results even with the poor screens that I have been able to make myself. With your very excellent screens the results will undoubtedly be very much better. The field of utility is enormous... Your success will be greeted with delight by all scientific men.602

Edison replied that he was working up a variety of X-ray tubes and was donating a number of them to hospitals where surgeons had quickly taken up the new X-ray techniques; he also sent them to various scientists, whose investigations, he noted, were “out of my line.”

Soon the newspapers, with an excitement rivaling that caused by the incandescent lamp of 1879, were reporting Edison’s progress in this new work day by day. He was going to photograph the human brain, it was said, and ever so many other formerly inscrutable or impenetrable objects. What could he not do with the miraculous new instrument? Among the hundreds of inquiring letters that came to him at this time was one urging him “to make an X-ray apparatus for playing against Faro bank.” The correspondent promised faithfully that he would share his profits with the inventor and besought him to keep the whole matter secret.603

While popular excitement over the X-ray ran high, Edison made a number of fluoroscopes, in the form of a box with a peephole at one end, exhibiting them at the Electrical Exposition held in 1896 at the Grand Central Palace in New York. Here thousands of persons came to peer through Edison’s fluorescent box and examine the shadows of their hands or other limbs, held between the vacuum tube and the screen. Some of them wanted particularly to have their brains examined, in order to learn, as one said, “if there is much in it.” It was at any rate the first public display of X-ray action in America, or perhaps in the world, and provided Edison with much distraction from the troubles of “industrial science.”

Before Edison could devise any commercial usage for the new X-ray machines, it was noticed at his laboratory that the primary or original X-rays were probably highly injurious. The fact that secondary and tertiary rays in a room where a powerful tube was being operated could give cumulative burns was not perceived. This was soon brought home to Edison when an assistant, Clarence Dally, was poisonously affected, so that his flesh became ulcerated, and his hair fell out. Several years later, after numerous amputations, Dally died. Edison had been experimenting with X-ray fluorescent lamps for lighting, but when Daily’s unhappy condition became apparent, Edison concluded that such a device “would not be a popular light” and so dropped it.

In the early stages of this work, he was by no means the only one to proceed without caution; many accidents occurred in hospitals and laboratories. Edison himself suffered from severe eye trouble which, at the time, was attributed by doctors to exposure to X-rays — though he recovered completely. In the 1890s little was known about radioactivity; X-ray machines were not made really safe until some fifteen years later, when operators began to use protective lead screens and “selectors,” and W. D. Coolidge’s hot cathode tube was incorporated in X-ray machines.

Other scientific “distractions” during the long years of rock-crushing were provided by intermittent development work on the phonograph. There was a great boom toward 1896 in the demand for low-priced phonographs and for cylinder records of music. Despite the competition of the Columbia machine and the new Berliner “gramophone,” Edison’s export sales in England, France, and Germany expanded rapidly and helped in part to repair his broken fortunes. After 1898 he was free of court restrictions and was again able to sell the Edison phonograph, equipped with an economical clockwork spring, in the United States. Work on the acoustical improvements for a large “Concert Phonograph” was also carried on by his assistants, under the inventor’s periodic supervision.

But surpassing all these activities in interest for Edison during the middle period of his life was his secret “toy,” the motion picture camera. This whole subject was both intriguing and difficult; he could see no practical commercial future for it and yet could not bring himself to drop it. If the balky and jerky kinetic camera could ever be brought to perfection, it might prove as “miraculous” as his phonograph and perhaps even save him from the ruin that overhung his affairs for years after 1893.

Our last glimpse of the motion picture camera was in the locked room at Orange, when Edison had returned in October, 1889, from his triumphs at the Paris Exposition, to be shown by his assistants a “kineto-phonograph” that actually functioned. In giving the story of a man who lived so many lives at the same time, we must use the film flash-back device (born of Edison’s own invention) and return to the secret labors of an earlier decade.

2

For a century or more men had used a variety of mechanical tricks with pictures in order to give the illusion of objects or living creatures in movement. Edison himself wrote that the germ of his idea came to him through acquaintance with the zoetrope, or wheel-of-life device, invented in the 1830s, which used the phenomenon of persistence of vision to create, for a few brief moments, the illusion of pictures in motion. In this scientific toy a series of drawings of objects in successive stages of movement were placed on the inside surface of a slotted cylinder or wheel, which, being turned on its axis, appeared to show those objects in movement to an observer looking through the slots.

By the 1870s the same effect was obtained even more impressively through use of photographs instead of handmade drawings. The most notable of these photographic experiments in demonstrating the persistence of vision were by E. J. Marey in France, and by Eadweard Muybridge in America. By an arrangement of a series of cameras along a race track, Muybridge took instantaneous photographs of horses in full gallop, the shutter of his cameras being actuated by wires or strings contacted by the horses. Using sensitive wet plates, already available, Muybridge was enabled to present a short cycle of movement in a dozen or so pictures. These he projected through a magic lantern, by means of a revolving device much like the wheel-of-life.

In the course of a tour of the country, giving illustrated lectures, Muybridge visited Edison in 1886 and showed him his pictures of horses, dogs, birds, and other animals in motion. Marey’s experiments in the analysis of movement, which were done with a single camera at the rate of twelve pictures to a second, by having a series of dry plates revolving on a wheel, seem to represent an even more advanced idea of pictures of motion. Both men’s work constituted a significant, but limited approach to the subject; in both cases, the effect of a rapid succession of pictures of a single cycle of motion, lasting a second or so, was that of a central object, say a moving horse, placed on a treadmill against a background that was racing past the viewer.

Edison’s mind, it has been said, was “a great reservoir of miscellaneous facts.” He informed himself upon all the recent advances in the photographic art. He had recorded the movement of sound. Could not the same thing be done in some way with the motion of objects or living creatures, for the sight? As long ago as 1864, a French amateur of science, L. A. Ducos, had actually worked out on paper the idea of a chain or film of photographs unrolling and, by the persistence of vision, giving the appearance of recorded movement. But he had never gone beyond the stage of a hypothesis. The pioneering efforts of Muybridge and Marey were highly significant, for the eye “saw” motion for a fraction of a second; they left Edison, however, unsatisfied. Yet their technical discoveries, their demonstrations of a scientific fact (persistence of vision), set the stage, so to speak, for Edison. He was aroused enough by what had already been attempted to go to work in their field and try to solve their problems himself.

In the autumn of 1887 the new laboratory at West Orange was completed. He was then extremely preoccupied with his improved wax-cylinder phonograph; but his mind was filled with all sorts of additional schemes. He had then revealed his idea of trying to make a camera that would record motion effectively to one of his assistants, the young Englishman named W. K. L. Dickson, who some years before had come all the way from London to seek work under Edison. It happened that Dickson was an impassioned amateur of photography, and often made photographic studies in connection with various experiments. As he remembered it, Edison one day engaged him in conversation in the yard outside the laboratory, disclosing a scheme for making a machine like a phonograph that would make pictures of objects in motion to the accompaniment of sound and voices.604

Shortly afterward, in December, 1887, Dickson was sent to the Scovill Manufacturing Company’s headquarters in New York to purchase special photographic equipment. In Number 5, an upper room of the new laboratory building, space was set aside for experiments with new photographic apparatus that Edison was to contrive. At the beginning of 1888, while his chief was putting the finishing touches on the improved wax-record phonograph, Dickson set to work making many tiny microphotographs, on dry plates, of persons and objects in motion. This series of photographs, as small as 1/16 inch square, or even smaller, when taken all together covered a short cycle of movement. But Edison had set himself the further problem of using the instantaneous camera to record movements in a continuous stream, and showing or projecting them with the effect of persistence of vision.

It is evident that he began with a fairly visual idea of the kind of mechanism he would use. This is clearly shown by the first document giving evidence of these early experiments — his caveat Number 110, written October 8, 1888, and filed with the Patent Office — which first describes such an apparatus:

I am experimenting upon an instrument which does for the eye what the phonograph does for the ear, which is the recording and reproduction of things in motion, and in such a form as to he both cheap, practical and convenient. This apparatus I call a Kinetoscope, “moving view.”... The invention consists in photographing continuously a series of pictures occurring at intervals... and photographing these series of pictures in a continuous spiral on a cylinder or plate in the same manner as sound is recorded on a phonograph.

He goes on to explain that when the picture was taken, the cylinder would be held at rest; then it would be rotated for a single step, halted again, and another exposure made. What he describes includes a photographically sensitized plaster cylinder geared to a mechanical movement that automatically rotates it and operates a camera shutter. A feed screw simultaneously shifts the cylinder lengthwise. The result is a spiral of pinhead-size pictures made directly on the coated drum. He remarks significantly enough, in this caveat, “A continuous strip could be used, but there are many mechanical difficulties in the way.”

Thus, after the first ten months of experimentation, during which he had studied the nature of a camera and viewing apparatus arranged both to take and view little pictures in motion, he had a clear, though general, idea of what he wanted, if not of how to get it. He had learned that while his phonograph must be run continuously, a camera record of pictures of motion would have to be run intermittently, with a stop-and-go action, at some speed still to be determined, so that persistence of vision would come into play for the viewer.

In this first search, carried on behind locked doors, Edison followed his own line of march, ignoring the findings of other men who had studied such phenomena. But at this stage, and for a long time thereafter, the idea of his phonographic mechanism controlled his thinking.

He had first fixed on about forty pictures a second as the rate necessary to get a perfect record of motion. Later that number would be reduced, as experiment showed was advisable. His cylinder machines gave him trouble, because the microscope used in viewing could not be focused evenly on the curved pictures. Also, the first photographs were too small and had to be increased in size from 1/16 to 1/4 inch to show good detail. It was tedious, even frustrating work.

The first cylinder apparatus made some sort of moving pictures. A fragment of one of the early models, still in existence at the Edison Laboratory, has a sensitized sheet of celluloid containing many diminutive pictures attached to a metal cylinder. The pictures show John Ott wrapped in a white sheet, waving his arms, and “making a monkey of myself,” as Ott said. The pictures were meant to be viewed directly, through a magnifying lens, and raised pins encircling one end of the cylinder apparently closed the circuit of an induction coil to illuminate the pictures intermittently with an electric spark.605

The pictures were exceedingly crude, especially when magnified. But Edison was hopeful now and reported to his patent lawyer that he was “getting results.”606

It was one of his special characteristics that he had, as has been said, an instinctive knowledge and discernment of materials. From the start he disliked the rigid and fragile glass plates then used in still photography, and experimented with new and improved photographic materials. When, early in 1889, he obtained from John Carbutt of New York, the pioneer of dry-plate making in America, some heavy sheets of celluloid coated with a photographic emulsion, his work took a long step forward. This tough, pliant sheet, about fifteen inches long, he could wrap around his big cylinder; he could also take the quarter-inch pictures in far greater number. At this stage he had a record of living movement running as long as five seconds.

In the late spring of 1889, Edison and Dickson, on the basis of their findings thus far, came to the decision that they must abandon the cylinder and contrive some radically different apparatus to provide the necessary stop-and-go movement for the camera shutter, while at the same time feeding a strip or tape of celluloid across the focal plane of the camera. Therefore, they cut up the Carbutt celluloid sheets into narrow strips which were cemented together end to end. The pictures of “slices of motion” could now be made still larger, with 3/4-inch-wide film and 1/2-inch frame, and could be run to a greater number of exposures, covering movements more extended in time. The coming of transparent celluloid film was, therefore, decisive in Edison’s search.

Further improvement in celluloid film was then made by George Eastman of Rochester, New York, the inventor of the rapid-action “Kodak.” His film was still tougher than Carbutt’s, yet light and flexible, so that it could be handled in rolls. On hearing of the new Eastman film, Edison promptly dispatched Dickson to New York to get a sample. Under Edison’s prodding, Eastman later produced specimens of celluloid, for his special use, in fair-sized lengths of fifty feet, instead of short pieces. When Edison was shown these long strips, according to Dickson, his smile was “seraphic.” He exclaimed, “That’s it — we’ve got it — now work like hell!”

In the summer of 1889 he designed a camera mechanism for advancing, that is, feeding the roll of film forward at a given rate of speed. The strip of film was drawn through rollers sideways across the focal plane of the camera and rewound automatically; perforations on one side of the film were engaged by a sprocket wheel attached to a main shaft that was revolved by hand or motor. An escapement or Geneva mechanism propelled the sprocket and moved the film intermittently, one step at a time, now forward, now resting; when the film stopped, a revolving shutter, also geared to the main shaft, rotated for one step, so that the exposure was made in the proper time relation. With this mechanism Edison obtained a series of photographs which, moving at a given speed, gave a pretty good illusion of motion.

The first machines of the early summer of 1889 were balky; the teeth of the sprocket wheel tore the strip film at the perforations, and the first Eastman film was coarse-grained. Edison was obliged to leave for Paris early in August, it will be recalled, but gave his assistants explicit instructions about further improvements to be sought. During Edison’s absence, they managed to complete pictures that lasted all of twelve seconds. When Edison returned from Europe on October 6, Dickson was bursting with pride as he showed him what had been done thus far.

According to Dickson’s statements, Edison himself overcame the many mechanical difficulties he had foreseen in the way of the development of the strip-film kinetograph at the time of his first (1888) caveat. He drew on the same mechanical ingenuity he had shown in his youth, when he first came to New York and devised his clever automatic-telegraph instruments and stock printers. After his motion picture invention became known to the public, everyone exclaimed over the simplicity of his apparatus — the strip-film kinetograph which solved both basic problems of the motion picture art: taking pictures of motion and exhibiting them. The same machine was used at first for viewing the pictures directly through a magnifying lens.

Edison’s first intention was to make sound pictures; he would synchronize the movement of the reel of film with a phonograph driven by the same motor powering the camera. There was to be singing or music accompanying a dance, or the sound of a voice as the film unrolled. “The establishment of harmonious relations between kinetoscope and phonograph,” Dickson wrote later, “was a harrowing experience, and would have broken the spirit of inventors less inured to hardship and discouragement than Edison.”607

With the thought of making the apparatus “commercial,” he also devised a peep-show mechanism for exhibiting positive prints made from his kinetograph negatives, which he named the “Kinetoscope.” This consisted of a cabinet of substantial size, containing batteries and a motor that turned the strip film on a spool bank and operated a light. In front of the cabinet was an eyepiece and lens; by looking through this the viewer saw the film as it moved along through a rotating screen with an aperture permitting him to glimpse only one picture at a time. Persistence of vision did the rest, giving the illusion of more or less lifelike motion.608

In the year that followed, Edison had his assistants build a better and larger motion picture camera for taking pictures one inch wide and 3/4 inch high, on film 1 3/8 inch in width, to allow space for perforations. This ponderous machine, which was in use between 1890 and 1894, is the true father of all modern motion picture cameras. The width of its film, 35 mm., is still standard today.

At this period of his life, in middle age, Edison worked much more slowly at his inventive tasks than in the past. Several different experimental projects were generally going forward at the same time, a team of men under his direction being assigned to each of them. In other words, he had the weight of a much larger research organization upon him at Orange than in the Menlo Park days. Four men, for example, worked on the motion picture job in the early stages, while it was still more or less a secret. Edison was just then leaving the electrical manufacturing industry, was experiencing much difficulty with the phonograph business, and was already deeply involved in his nerve-wracking ore-separating work. Thus he did not even file for a patent on his basic 1889 kinetograph and kinetoscope until the end of July, 1891 (Nos. 493,426, and 589,168); and those patent applications were, as it happened, incomplete and faulty. Two of his photographic assistants, not long afterward, left his employ to work for others who entered into competition with Edison in the new industry created by his invention. These competitors fought him in the courts to contest his patent claims, in the course of which litigation it was alleged that one of his assistants, Dickson, performed a large part of the inventive work on the motion picture, and that, anyway, there was “nothing new” in Edison’s invention that had not been tried previously by other men. In short, his work on the motion picture camera was more disputed and disparaged than almost anything he ever did.

Marey and Muybridge were indeed his scientific precursors, whose work had the element of discovery of a mechanical principle. Edison himself, in 1894, made handsome acknowledgment to them as his forerunners. His own contribution to the art, nevertheless, was highly strategic and creative. Once again we find him entering a field of investigation in which many persons had preceded him and where the general scientific principles were already understood. But with his coming things begin to move. The art and industry of the motion picture at last is born.

The distinction between his work and that of his forerunners lay in his original use of a single point of view from the one, fixed camera’s eye, so that in his pictures a man could be seen walking from one end of a room to the other, while its walls and the whole background image remained still — instead of rolling past our sight as in the sliding stage-sets of the old theater. Edison’s great trick was the adaptation of the instantaneous camera and the flexible Eastman celluloid film, so that strip film (instead of plates) could be fed across the focal plane of the camera. There was indeed “nothing new” in the several materials and mechanisms he utilized.609 But once again, we have an instance of what many have regarded as Edison’s preeminent gift — “the ability so to adapt or combine ideas or materials already existing as to effect results at once distinctively new and thoroughly practical.”610

The cumbersome Edison motion picture camera of 1889-1890 was the first machine that photographed objects in motion effectively. We need only view one of these early models of the strip-film kinetograph, in the museum of the Edison Laboratory National Monument at West Orange, and compare it with its predecessors, to realize this truth. (The English, to be sure, give “priority” to one L. A. A. Le Prince, who in 1886 patented a tape-reeling camera of multiple lenses, which, however, is known to have been completely inoperable.)

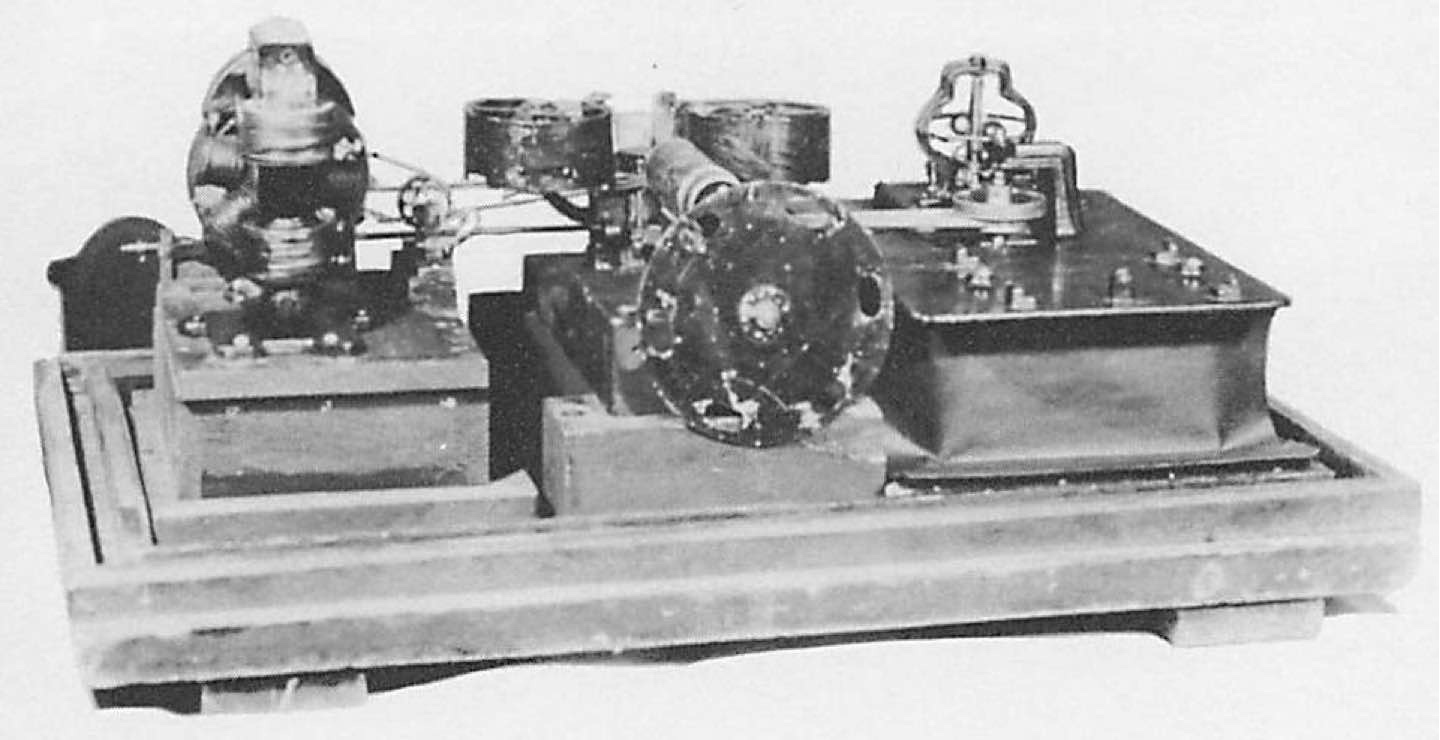

Strip kinetograph of 1889: the prototype of the motion-picture camera.

A further significant contribution was the little black box he called the Kinetoscope, providing the world with a first exhibiting mechanism that used positive film in rapid movement, seen through an eyehole. It offered the first motion picture show in history. As Terry Ramsaye, historian of the motion picture, has said, the Edison peep-show is the “inescapable link” between past and present in this field. “There is not and has never been any motion picture film machine... that is not descended by traceable steps from the Kinetoscope.”611

The Peephole Kinetoscope, commercially manufactured in 1894. Moving strips of film were viewed through the magnifying eyepiece on the top.

3

For a period of almost two years a good deal of mystery surrounded the new apparatus and the first small wooden frame photographic building (erected at a cost of only $516) in which it was locked up. After his betrayal by Gilliland, Edison, the once openhearted country boy, became fairly secretive. Only a few trusted and favored friends, such as his patent lawyer Richard N. Dyer, were permitted to witness private exhibitions of the new piece of “wizardry.”

In one of the first authoritative articles written on the motion picture machine after news of the invention became public, Dickson relates:

On exhibition evenings the projecting-room, which is situated in the upper story of the photographic department, is hung with black, in order to prevent any reflection from the circle of light emanating from the screen at the other end, the projector being placed behind a curtain, also of black, and provided with a single peep-hole for the accommodation of the lens. The effect of these somber draperies, and the weird accompanying monotone of the electric motor attached to the projector, are horribly impressive, and one’s sense of the supernatural is heightened when a figure suddenly springs into his path, acting and talking then mysteriously vanishing.612

There was a good deal of whispered gossip, nevertheless; and in June, 1891, the first vague newspaper accounts of the apparatus were published.613 Edison thought it wise to file for a patent on an “Apparatus for Exhibiting Photographs of Moving Objects” (No. 493,426) on August 24. In his first caveat on the primitive kinetograph of 1888 he had referred to the possibility of using a projecting apparatus and a white screen; but in his patent application of 1891 that idea was dropped. Those early photographic exposures usually glinted and jerked about a good deal; when magnified and projected on a screen the effect was even poorer visually. It seemed to Edison that pictures of motion were under much better control in his little peep-show box, which might be used, like the phonograph, as a coin machine for popular entertainment.

The omission of the projector-and-screen device would prove later to be unlucky for him. He committed another and even more costly error by failing to take out foreign patent applications for his motion picture camera in England and Europe. As a matter of routine his lawyer advised him to file for such foreign patents. But when told that it would cost $150, he is reported to have rejected the proposal, saying casually, “It isn’t worth it.”614

These two legal errors opened the door wide to competition by many rival inventors, borrowers, infringers, and plain pirates. Once a model or even a drawing of Edison’s motion picture camera was available in Europe, anyone could imitate it and have it patented in his own name and offered in the United States market as well as that of Europe. On the other hand, while Edison was then greatly harassed by other problems and could not give his undivided attention to the motion picture project, his imitators, as it happened, were able to introduce improvements upon his ideas and eventually to advance the motion picture art beyond the point where he had stopped. It is a curious aspect of the patent law problem that imitation and even infringement often breed technical progress.

As late as 1893, in a friendly note to the aged Muybridge, Edison wrote:

I have constructed a little instrument which I call a Kinetoscope, with a nickel and slot attachment. Some 25 have been made, but am very doubtful if there is any commercial feature in it, and fear that they will not even earn their cost. These Zoetropic devices are of too sentimental a character to get the public to invest in.615

He testified later that for several years his efforts to interest capitalists in promoting this machine proved vain.

By 1893, however, some enterprising men had begun to see promise in the queer little peep-show box. Thomas Lombard, who promoted the sale of coin machine phonographs for Edison’s company, happened to be admitted to one of the private exhibitions at West Orange, and strongly urged the inventor to let him present the kinetoscope to the public at the approaching Chicago Exposition. There were some amusing “shorts” on hand, showing John Ott, his walrus mustache waving about, doing an Arabian “skirt dance,” and of the same pioneer motion picture star going through all the phases of a prolonged sneeze — accompanied by some poorly timed sound effects on the phonograph. But Edison was unable to get this coin machine apparatus ready for the Chicago fair.

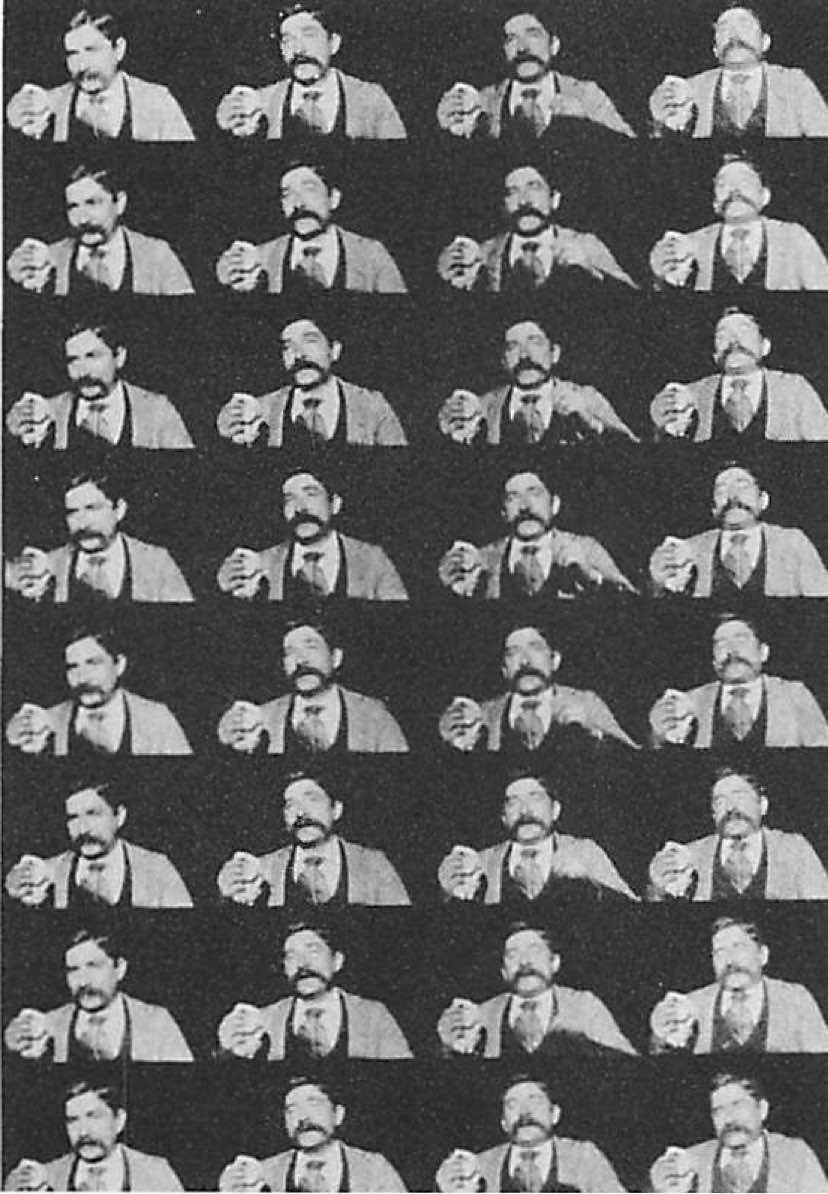

“The Record of a Sneeze,” starring Edison’s assistant Fred P. Ott. The first motion picture ever copyrighted (1894).

After having neglected the motion picture invention — in favor of low-grade iron ore and the phonograph — Edison’s interest in the affair finally began to wax. On February 1, 1893, a strange new building, dedicated to the new art, soon reared its ugly form within the Edison Laboratory “compound.” It was something the like of which had never before been seen and would probably never again be seen either in this world or the next — a wooden structure of irregular oblong shape, with a sharply sloping roof hinged at one edge so that half of it could be raised to admit sunlight. The whole building, fifty feet in length, was mounted on a pivot, like a revolving bridge, and could be swung around slowly to follow the changing position of the sun and admit its full glare to the interior. The walls of this jerry-built affair (total cost under seven hundred dollars) were covered with black tar paper; the stage at one end of the single large room was also draped in black, so that the whole décor was funereal in the extreme. Such was the first building constructed especially as a motion picture studio, officially called the Kinetographic Theater, but affectionally referred to by its staff as the “Black Maria.”

In this somber edifice a spate of pygmy motion pictures was “ground out” in 1893 and 1894. The performing artists were drawn, as Dickson relates, from every walk of life and “from many a phase of animal existence” as well. They strutted for a brief moment of glory — the shorts now ran about a minute and a fraction — in the full glare of that sunlit stage, against a background so dark that the pictures were quite sharply defined. Among the early performers was “Gentleman Jim” Corbett, pugilistic idol of America, who provided a realistic exhibition of his art. As Corbett related, many years afterward:

The Black Maria certainly did look like an old-fashioned police patrol wagon. We hadn’t been inside very long before most of us would have preferred a police patrol at that — for the little moveable studio was the hottest, most cramped place I have ever known.

The camera in use could take only an average run of 1 minute 20 seconds. The pictures... were only about six inches high and you looked at them through binoculars. But you could distinguish all the details of the action.616

A third-class pugilist from Newark had originally been hired to serve as Corbett’s sparring partner, though without being informed of the name of his opponent. But when he reached West Orange, the lugubrious stage setting as well as the prospect of contending with Gentleman Jim so affected his emotions that he ran all the way back to Newark. However, a replacement was found for him at Edison’s usual low rates, about ten dollars for ordinary performers and fifty dollars for celebrities, and the historic film was completed. Other performers were the famous strong man Sandow; Japanese dancers; French ballet girls; “Buffalo Bill,” with accompanying Indians, recording a first “Western”; also acrobats, knife throwers, and divers fowl recruited for cockfights.

In one of his frivolous moments Edison went off to Daly’s Theatre in New York and persuaded its celebrated Gaiety Girls and their leading lady, the beautiful Mae Lucas, to come to his studio and dance before his kinetograph. After such efforts it was an easy step to film short comedy skits from the vaudeville stage, as well as picturesque renditions of an organ-grinder performing with his monkey, or of a patient in a dental parlor reacting to treatment with laughing gas.

The camera’s eye was also pointed outside the windows of the Edison Laboratory to take realistic views of everyday life along Valley Road, West Orange. These might be called the first documentaries. One sequence is a truly lifelike study (dating from 1897) of Edison himself working in his laboratory, while one assistant after another seems to come racing in to give his report and receive lightninglike orders. The inventor cups his ears, barks out instructions, and hurries on with his work until the next man comes running in with other troubles for him. (The pictures, having been taken at 16 exposures per second, and being nowadays shown at 24 a second, are speeded up.) Then one day the quiet of West Orange is shattered by the thunder of battle, as uniformed horsemen, simulating the British and the Boers in Africa, go charging over the empty lots outside the Laboratory — to the vast amusement of the eternal American boy in Thomas A. Edison.

In the early stages of the art, however, it was the exhibition of prizefighting contests that was to create a first popular vogue for Edison’s pictures in motion and bring him sudden fortune again. Early in 1894, Thomas Lombard, who had been so enthusiastic about the peep-show, turned up with a young capitalist named Norman C. Raff, recently arrived in the East from gold-prospecting exploits in the Rockies. Edison’s former Wall Street friends, such as Villard, would not go near his motion picture invention; Edison himself at the outset seemed a bit ashamed of its apparently delinquent character. But Raff and Frank Gammon, an associate whom he soon introduced, were another breed — speculators, backers of race track entries or theatrical shows. They saw the skits and prize fights, and in 1894, after organizing the Kinetoscope Company, entered into a contract with Edison to purchase a large number of his peep-show boxes for two hundred dollars each and exhibit them in “Kinetoscope Parlors,” furnished with film and coin machine boxes.

The first of these parlors was opened on lower Broadway in New York, on April 14, 1894, and was billed as “The Wizard’s Latest Invention.” There had been a few illustrated lectures previously; but this was the first public showing and created something like a riot. Crowds on Broadway waited all day and far into the night in long queues to see the pictures that lived and moved for ninety seconds through the eyeholes of five kinetoscopes. Soon there were similar parlors opened in Chicago, Baltimore, Atlantic City, San Francisco, and other centers, which were also besieged by crowds. The exploitation of the motion picture was thus begun as a form of mass entertainment, following the commercial pattern of the earlier phonograph parlors.

On one day in the summer of 1894 a gory ten-round boxing match was staged in the Black Maria between two professional gentlemen named Mike Leonard and Jack Cushing. It ran to a thousand feet of film and ended in a real-life knockout of Mr. Cushing. When this picture was shown, in six reels and through six different kinetoscopes, by one of Raff and Gammon’s licensees in New York, it drew almost riotous crowds for many days on end, and the police had to be called in to keep order.617 The motion picture, even in the diminutive films of the Edison peep-show box, had conquered the great masses. The impact that this new entertainment medium was to have upon the minds and lives of hundreds of millions throughout the world was something unforeseen and unimagined — perhaps surpassing the effect of almost all other nineteenth-century inventions, by Edison or anyone else.

4

Edison had shown the insight of the born inventor in his mechanical work on the motion picture in 1888-1889. After he had perfected his kinetoscope he permitted himself some prophecies as if referring to the distant future:

The kinetoscope is only a small model illustrating the present stage of progress, but with each succeeding month new possibilities are brought forth. I believe that in coming years, by my own work and that of Dickson, Marey, Muybridge, and others who will doubtless enter the field, grand opera can be given at the Metropolitan Opera House at New York without any material change from the original, and with artists and musicians long since dead.618

But for all his clairvoyance, he could not foresee the great developments that were to take place within a comparatively few years. Nor did anyone else really foresee them. Meanwhile he halted his efforts to develop the peep-show machine into something superior, projecting life-sized motion pictures. There is no doubt that he and Dickson attempted in 1889 to project pictures upon a wall screen five feet square. But the effect was of a flickering blur; the problem of magnifying the picture and illuminating the screen remained technically difficult, compared with the operation of stationary stereopticon slides shown with an optical lantern. The peep-show box with its rotating shutter gave, by comparison, very clear flashes of vision. When the first backers of his motion picture work urged Edison, in 1895, to give them an apparatus projecting film on a screen, he at first refused, then casually assigned the task to one of his machine shop men. He remarked at the time that if he could give his whole attention to the problem for a week he would “get it going.” But he never had the time, after his first fine thrust at things kinetographic.

Meanwhile, two brothers named Otway and Grey Latham, who had been showing the Leonard-Cushing and other boxing films with much profit, under license from the Kinetoscope Company, had realized how awkward it was to have the crowds of viewers move from one box to another to see a minute’s record of the fight in each. If they could manage to project the whole motion picture on a sheet against the wall, one of the Lathams remarked, “there would be a fortune in it.” In other words the motion picture ought to be taken out of Edison’s little box and shown in theaters where people could sit and watch the entire thing without interruptions.

When the idea was broached to Edison, however, he said firmly no. The great inventor was certainly playing the stubborn Dutchman again. He had said earlier that the flat disk, or plate phonograph record, would never amount to anything, and failed to patent his own version of it, so that others afterward, with the help of Emile Berliner, were to make millions out of the flat record. Now, when approached by Norman Raff, his business associate, to develop a screen projection camera, he asserted that he was going to stick to the peep-show box at all costs; “If we make this screen machine that you are asking for, it will spoil everything.” At the moment they were selling a lot of peep-show boxes at a good profit; but if they put out a screen projection machine, Edison estimated about ten of them would take care of the demand for the entire country! At that rate there would be no profit in it. “It was better,” he advised, “not to kill the goose that laid the golden eggs.”619

He continued in this course, even after he learned that the Latham brothers, with the aid of their father, a professor of chemistry, had begun secretly working out a screen projection apparatus of their own in a small laboratory in New York. This is a turning point in the history of the new entertainment industry. It must be remembered that, at the time, Edison held potential control of all the processes of motion picture making. He had invested $24,118, over five years, in the kinetoscope’s development, was winning it back quickly, but clung to his narrow view of the industry’s future prospect. In truth the “craze” for the motion picture peep-show, after two years, showed signs of dying down.

Now began a chaotic race among inventors of all sorts — as well as mechanics, plumbers, and even steam fitters — to perfect a screen projecting apparatus for Edison’s films. In France, Marey and Louis Lumière were soon developing excellent motion picture devices of all sorts; and in England R. W. Paul likewise. Their machines, appearing toward 1896, could be used in America in conjunction with a screen and a projector. There would be cutthroat competition and lawsuits on every hand; in the end, Edison by his great blunder in 1894 was to lose what was later reckoned to be a “billion-dollar monopoly.” (We speak, here, from hindsight.)

In 1895 he also lost his ablest photographic assistant, William K. L. Dickson, a thin young Englishman with waxed mustache and goatee and an artistic temperament, who for nigh on fifteen years had shown an almost filial attachment to his chief, and served him cheerfully for thirty dollars a week. Next to Edison, he knew probably more than anyone else about the mechanism of the motion picture camera and kinetoscope. While much credit is owing to him as Edison’s principal aide in these investigations, it would be absurd to say, as some have done, that on the motion picture he did “most” of the work credited to Edison. In the adulatory biography of the master that he published in 1894, and in various articles before and since then (despite their later estrangement), Dickson himself made no such assertions. The key ideas were always Edison’s; he always passed on their execution by other hands, including Dickson’s. After Dickson left West Orange, he achieved virtually nothing during the next forty years of his life.

However, he had worked with Edison in 1889 over one or two primitive projecting systems using a screen, though the first results were poor. He wanted passionately to go on with projecting, but the master thwarted him. Then the Lathams set up their independent laboratory, and — by a shadowy maneuver — first lured away one of Edison’s technical assistants, a French photographer named Eugene Lauste. Next they made covert approaches to the more expert Dickson.

Now a new figure appears on the West Orange scene, a big bustling man named W. E. Gilmore, who in April, 1894, had been engaged by Edison to act as his financial manager and who was expected to set the chaotic Edison affairs in some order. Hearing rumors that Dickson entertained covert relations with the Lathams, Gilmore roundly accused him of dishonorable conduct and demanded that he be fired. Though Edison refused to believe such charges then, he ended by agreeing to his dismissal. And so Dickson went over to the Lathams, who, in the spring of 1895, were to launch their imperfect motion picture projector.620 Later it was noticed by Edison that various notebooks relating to some of the early experiments they had made together on a projection camera and screen had also disappeared around the time of Dickson’s departure.621

The Lathams’ magic-lantern kinetoscope, called the “Pantoptikon,” made a passing sensation in the press. It was nevertheless a crude affair, that probably helped to attach to the new art the colloquial name, “flickers.” Their motion picture camera, however, obviously infringed upon Edison’s patents, and he at once threatened suit. At the same time, he promised to build a better projecting machine himself.

The productions of technical workers in this field now appeared in torrents. Someone, at the Lathams’ laboratory, hit upon the reel, as a superior device for handling the long film strips; in France, the gifted Lumière cut down the number of exposures per second from Edison’s 46 to only 16, yet maintained an excellent effect of persistence of vision. Finally, in 1896, Thomas Armat, of Washington, D.C., an amateur of the camera, developed new gear for his projection lantern (the “vitascope”) that permitted the positive film a longer period of rest and a shorter period of movement. Each individual picture was thus allowed more time to be illuminated on the screen and fill the eye, an important step toward good projection. The completion of Edison’s promised “screen machine,” meanwhile, had been delayed. When the distributing agents for the Kinetoscope Company, Raff and Gammon, saw what excellent results Armat had obtained with his projection device, they promptly bought an option on it. “We thought it would be a great deal better for us to control the machine than to have it fall into the hands of parties unfriendly to you and us,” they wrote Edison in January, 1896. Since Armat’s “screen machine” worked so well, and Edison’s was not ready, why should they not join forces and combine Armat’s projection device with the Edison motion picture camera? They proposed, moreover, that the Edison company should manufacture all the Armat projectors, or vitascopes, and sell them under the Edison label.

At first the veteran inventor made some difficulty about accepting this proposal; and Thomas Armat was loath to make an accommodation that would deny him credit for his important contribution to motion picture progress. But, as Raff argued in a letter to Armat, no matter how good a machine should be invented by another, the customers would prefer Edison’s:

Kinetoscope and phonograph men and others have been watching and waiting for a year for the announcement of... the Edison machine which projects kinetoscopic views upon a screen or canvas. In order to secure the largest profit in the shortest time it is necessary that we attach Mr. Edison’s great name to this new machine. While Mr. Edison has no desire to pose as the inventor of this machine, yet we think we can arrange with him for the use of his name and manufactory.622

It is a sorry episode in the great inventor’s career; and it was with evident reluctance that he, who had contrived so much, now yielded and agreed to lend his name to the product of another. At this time there were persistent rumors that Edison was in financial difficulties, and they were not far from the truth. An agreement was reached that satisfied neither inventor. It was, in fact, terminated a year or so later when Edison devised his own projection gear, and Armat took back his patent rights. Several years later the whole affair was ventilated in court during the suit between Edison and the Mutascope Company. Edison then testified that there was little difference between his own earlier projection machine and Armat’s, except for the latter’s “egg beater,” or intermittent, movement. Yet it was that difference in movement that was all-important.623

Meanwhile, in 1896, Edison and his associates anticipated big profits, as preparations were made to open theaters with wall screens. A first showing of the new vitascope projector was given before newspaper reporters in one of the large shops at West Orange. Annabelle, a great theatrical favorite of the day, with attendant dancing girls, appeared life-size, and in color too, on a screen 20 by 12 feet. It was a frosty morning; Edison, wrapped in two overcoats, walked about looking highly pleased, and said, chuckling, “This is good enough to warrant our establishing a bald-head row, and we will do it too.” The press mistakenly publicized the new projection machine as “Edison’s Latest Triumph.”

The formal public presentation of the “enlarged Kinetoscope” took place on the night of April 23, at Koster & Bial’s fashionable Music Hall on Herald Square, before a silk-hatted audience embracing many leading figures in the theatrical and business world. This event signalized the introduction of living pictures to the theaters of Broadway, and thereby to all the world. The presentation included ballet girls dancing with umbrellas, burlesque boxers, some vaudeville skits, and finally so realistic a scene of waves crashing upon a beach and stone pier that some of the viewers in the front row recoiled in fear. The audience was astonished and exhilarated by this newest “miracle of science,” and sent up great cheers for Edison. Thomas Armat, who had agreed to stay in the background, was working in the projection booth to keep the machine in adjustment; the gray-haired Edison was in a box, but refused to come forward and respond to the applause of the crowd for the success of “his” vitascope.624 From that time forward, the magic of the motion picture took hold of men everywhere. Charles Frohman, the dean of the American theater, who was present, expressed the fear that henceforth no one would want to look at the dead scenery of the stage, painted trees, frozen waves, and the like.

After the combined work of Edison and Armat, there was left for others only the refinement of motion picture technique. For many years, however, the “movies” remained limited in subject to short recordings of dances, prize fights, comic skits, and freak performers, which became an established feature of hundreds of music halls and “arcades” throughout America and Europe. Though Edison himself was an imaginative storyteller, he had no concept of how the motion picture could be made an art form. His attention remained confined to the improvement of its techniques and the profitable manufacture of cameras and projection machines. The “shooting” of films in the Black Maria was delegated to others.

With the coming of the motion picture, a medium almost unlimited in its scope, both as visual art and dramatic representation, had been created. A Chinese proverb holds that “one hundred tellings are not equal to one seeing.” The motion picture brought a new power of seeing.

Its future development was first foreshadowed, though dimly, in 1903, when an Edison camera man at the Black Maria, after seeing some French experimenter’s “story film,” brought forth a work entitled The Life of an American Fireman. It was conceived in the form of a dramatic sequence and packed with sudden disasters and heroic rescues. This effort was quickly followed by The Great Train Robbery, distributed by Edison’s studio in 1904, and now regarded as the classic prototype of the motion picture play. A flood of Westerns and thrillers, having the literary quality of the dime novel, quickly followed and generated a great new wave of popularity, even though the films ran to only 1,000 feet at most, so that the action had to take place at breakneck speed and came to a jarring halt after about fourteen minutes. Now, little motion picture theaters and nickelodeons mushroomed all over the country; by 1909 there were about 8,000 of them, a figure that was soon afterward doubled. From a relatively small amusement business, the movies within a few years were to be transformed into a major industry. Who could have known, from seeing the absurd little “shorts” of 1896 to 1903, that untold millions of human beings throughout the world would soon come to live vicariously in the darkened cinemas and share the joys and sorrows of the stars, Mary Pickford, Lillian Gish, and Charles Chaplin?

Despite vigorous competition, Edison’s film company expanded rapidly and built a large glass studio in the Bronx at a cost of $100,000. The Thomas A. Edison, Inc., label became known throughout the world. But the conditions of this new mass entertainment industry were such that its administration was distasteful to its founder, and he delegated it to others. The Edison pictures, like those of most competitors, aimed at entertainment on a low level, artistic standards being set by the rampant commercialism of the film producers and distributors.

Though Edison was for some years the largest, or nearly the largest, manufacturer of motion picture machines and films, numerous strong competitors were now ranged against him — Biograph, Vitagraph, Essanay, Kalem, Lubin, B. F. Keith, and others. It must be remembered that by his blunder in failing to apply for European patents for his motion picture apparatus in 1891, Edison had lost the monopoly of the process of film making; his various competitors in the industry had purchased American patent rights to English and French machines that were obvious imitations or improved models of his invention. There were prolonged patent wars in court with the firms controlling the Latham, Armat, and various foreign patents. The selling and distribution of both films and cameras was for years a chaotic business; not only were manufacturing patent rights infringed upon, but films themselves were “duped,” that is, duplicated, without payment of fees to their owners.

After ten years of litigation, Edison won a verdict upholding his original motion picture patents of 1891 in Federal court, at Chicago, in October, 1907. At this point some of the larger defendants, especially Jeremiah J. Kennedy, of the Biograph Company, made overtures to Edison’s financial manager at the time, Frank L. Dyer, with a view to bringing about law and order in the industry. Kennedy’s plan called for a pooling of patents and setting up a centralized control over both producing and distributing of films, by means of a national trust agreement under the Edison licenses. Dyer, Kennedy, and the representatives of eight other film-producing companies (two of them foreign concerns) soon afterward organized the Motion Picture Patents Corporation, whereby all the producers in the group recognized Edison’s patents and guaranteed him payments of several hundred thousands annually in royalties for their licenses. Provision was also made for a national system of exchanges under which almost all screen theaters in the country were to pay the trust weekly fees for each projection machine, while the nationwide distribution of regular “packages” of film reels was also strictly controlled in the interests of the trust, by fixed allotment of the business among its members.

It was an affair of the most dubious legality in that era of “trust busting.” Nevertheless, until the lawsuits of independents, such as William Fox and Carl Laemmle were settled, and before the suit of the United States Attorney General charging conspiracy fell upon their heads, the major film producers could look forward cheerfully to years of assured profit. The formal signing of the trust agreement in December, 1908, was made the occasion of a sumptuous banquet held in Edison’s great library, in the laboratory at West Orange.

Edison received these former opponents most cordially, and in his highly informal manner. He ate quickly, then said, “You boys talk it over, while I take a nap.” On a cot placed in a corner of the library he dozed off soundly, while discussion among the scheming film magnates raged on. Conceivably he did not care to know in detail what they were talking about. When it was over he was awakened. “All right, where do you want me to sign?” he asked. He made no pretense of reading the perfected document and, explaining that he had some difficult experiments under way, said, “Good-by boys. I have to get back to work.”

The “patent trust” and its distributing branch, the General Film Corporation, endured for almost ten years, until the United States Supreme Court finally ordered its dissolution, in April, 1917, under a consent decree. But during that long interval Edison’s film company, as one of the leading participants in the trust, derived profits of up to a million a year from royalty fees and allotments of its film productions.625

In the late nineties, after he had severed his connections with the General Electric Company, Edison had been on the verge of financial ruin, thanks to the failure of his ore-separating venture. In 1898, in response to a kindly letter from Henry Villard inquiring if he needed help, he had written cheerfully from his Ogdensburg mine that he hoped, at any rate, to be able to clear off the debts he had incurred. “My three companies, the Phonograph Works, the National Phonograph Company, and the Edison Manufacturing Company (making motion picture machines and films) are making a great amount of money, which gives me a large income.”626 At that time he was still pouring his revenues into the ore-milling works.

But soon after he gave up that stubborn campaign, he was in the black again! Edison cared nothing for mere money, as against the joy of a new battle to wrest from nature more of her secrets — but he could always earn his way. By his wits, with the help of his ingenious kinetoscope, and a few other tricks, he had saved himself again.

At this time of his life, when he was almost sixty, he told an interviewer:

The point in which I am different is that I have, beside the inventor’s usual make-up, a bump of practicality... the sense of the business-money value of an invention. Oh, no, I didn’t have it naturally. It was pounded into me by some pretty hard knocks.627

Once more, in the early years of the new century, he felt like the Count of Monte Cristo. With his recent winnings he could now afford to “plunge” into a new, a different, and a very hazardous experimental project.

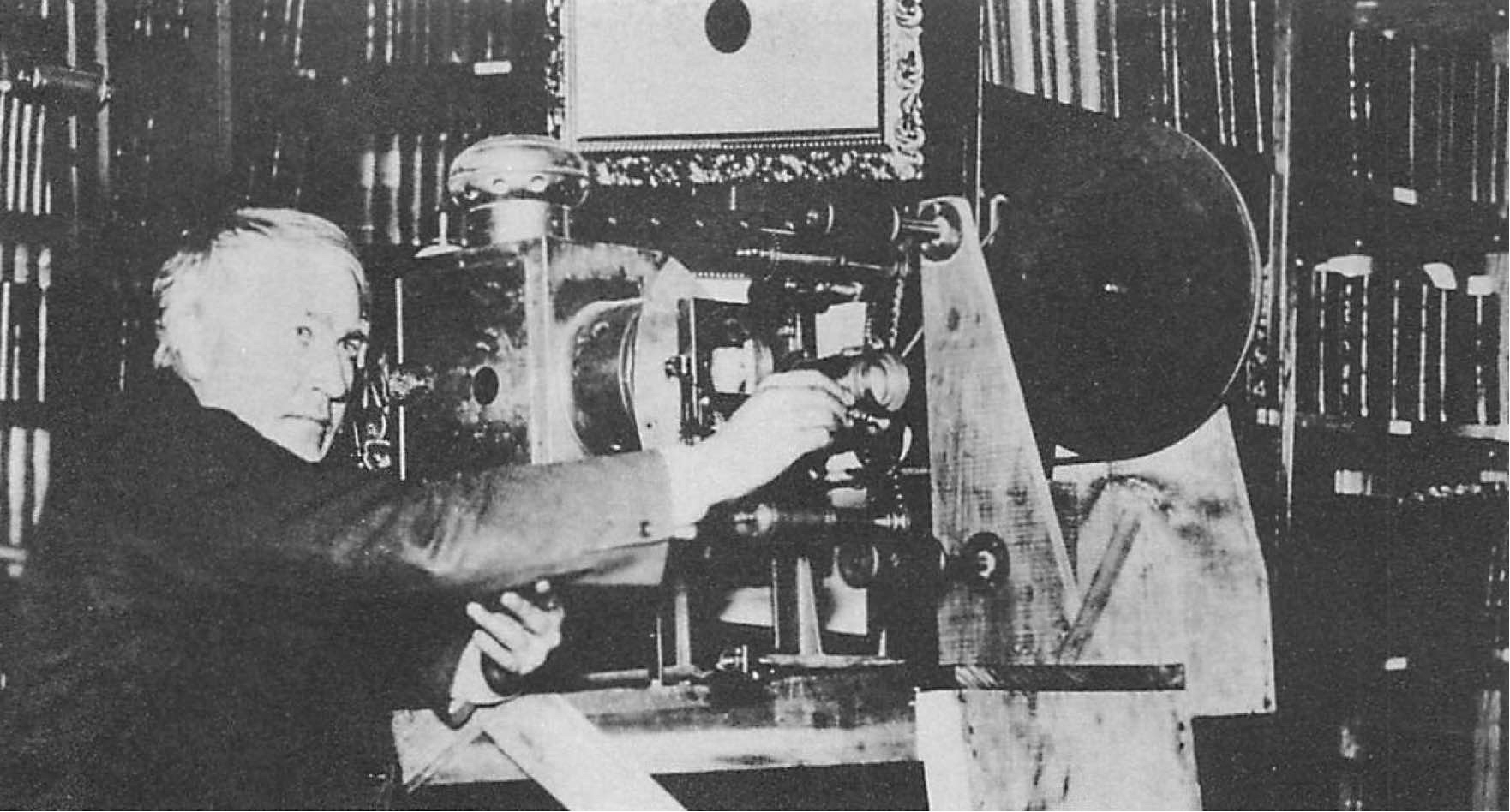

Edison operating an early motion-picture projector in the library of his West Orange laboratory (1897).