2 ~ Childhood and boyhood

1

Six years passed. The child Alva — or “Al,” as he was usually called — though often ailing, grew up to boyhood in Milan. Then, one morning in 1853 a knot of people, some accompanied by their children, gathered together in the cobbled square to look on at a strange rite: Sam Edison, the lumber and feed dealer, was whipping his youngest son, Alva, in the village square. It was like a scene out of the time of the Puritans in New England.

Physical punishment of a child, even in private, has often been found to be of dubious value; Rousseau had condemned it with all his eloquence a hundred years earlier. A public chastisement, carried out in cold anger, in the presence of the neighbors and their children — Sam Edison had advertised the event in advance — was something drastic and could only have been thought condign to some extreme wrongdoing. The boy’s mother was said to have been tender-hearted as well as intelligent; neither parent, in fact, could have been considered cruel for those times, when children were regularly whipped at home and in school.

That the youngest Edison boy was something of a problem child, or was at least a difficult one, was generally believed by the neighbors of the Edisons. For he was of a decidedly mischievous bent and was forever falling into scrapes. The latest and most serious of these had occurred a day or two before and had resulted in the burning of his father’s barn in the yard below the house. Alva had set a little fire inside the barn “just to see what it would do,” as he innocently enough explained it. The flames had spread rapidly; though the boy himself had managed to escape from the barn, the whole town might have gone up in smoke if there had been a strong wind. Hence his father had devised a punishment to fit the crime, one that would be improving (though also no doubt secretly enjoyable) for the neighbors’ children.

The public thrashing he received stamped itself on the boy’s mind and memory, for Thomas A. Edison described it all, though with wry good humor, sixty years later, when he thought back upon his boyhood.13

From his few words we have a picture of the boy, too small not to weep, receiving blow after blow, and early in life learning that there was inexplicable cruelty and pain in this world. (In later times he showed a curious indifference to physical suffering, whether his own or others, and bore pain himself without signs of emotion.)

If some deep and enduring resentment against his father was lodged in his subconscious, he did not show this overtly. While in later years he spoke with marked affection of his mother, there is no record of his having ever said anything complimentary on the subject of his father. To the latter, however, he was always a loyal son. The little that he did say in recollection suggested clearly that there was no understanding between his father and himself. “... My father thought I was stupid, and I almost decided I must be a dunce,” was one of Edison’s few plain references to this parent.14

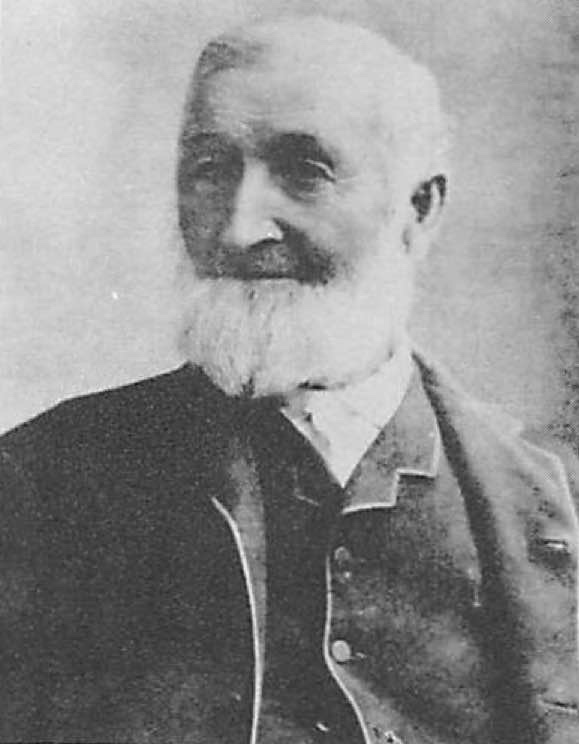

Samuel Edison, Jr., Thomas Edison’s father.

His father, for his part, said on a number of occasions that he could make nothing of his son and that the boy seemed wanting in ordinary good sense. He was trying, he was vexing, as have been many other unusual children before and after him; he was forever curious, forever asking “foolish questions.” The harsh corporal punishment visited so publicly on Alva, meanwhile, did not serve to make him mend his ways, or even to keep him from playing his little tricks on people. While his parents tried their best to rear him properly — his mother especially exerted herself to this end — he seemed in childhood and youth to be one who just grew in his own way.

The tales collected about his childhood in the small Ohio town show him to have been at first a grave infant who seldom cried. For some years he slept in a crib in the tiny windowless attic room under the eaves which he shared with two other Edison children, Harriet Ann and Pitt. They were much older than he — by fourteen and fifteen years — while the children who came in between had died. As for the eldest sister, Marion, she was married when Alva was two years of age. The infant was taken to Marion’s wedding and was held in arms during the ceremony.

He seems to have had few childhood companions, and he played alone with his toys a good deal of the time. One of his earliest memories was the sight, in 1850, of long trains of prairie schooners drawn up in the narrow roads of Milan; these people, he was told, were going to the gold fields of California. But where was “California”? and what was “gold”?

As soon as he could talk he began to ask his parents and everyone else his interminable questions. There were so many “whys” and “wheres” and “whats” that Sam Edison said that he often felt himself reduced to exhaustion. Alva’s mother, however, was more patient.

“Why does the goose squat on the eggs, Mother?” he would ask.

“To keep them warm,” she replied.

“Why does she keep them warm?”

“To hatch them, my dear.”

And what was hatching? “That means letting the little geese come out of the shell; they are born that way.”

“And does keeping the eggs warm make the little geese come out?” he went on breathlessly.

“Yes.”

That afternoon he disappeared for hours. “We missed him and called for him everywhere,” it is related in a story that has come down through his sister Marion’s family. He had disappeared into their neighbor’s barn. At length his father found him “curled up in a nest he had made in the barn, filled with goose eggs and chicken eggs. He was actually sitting on the eggs and trying to hatch them.” Such a little goose he was — yet a logical goose!15

His favorite playground was the terrace outside the kitchen, where he was under the eye of his mother. Here he could gaze down the slope at the canal basin two hundred feet away, with its sailing and steam vessels and barges riding in as if through the fields. Down below were the busy shipyards of Merry & Gay, the Yankees who had laid out the town and later built the canal. There was a large flour mill, a brewery, grain elevators, a tannery, smithies and iron forges, making an animated scene of local industry. The place was loud with the noise of six-horse teams, the crack of bullwhips, the “Gee-haw!” of drivers. Finally, there was his father’s wonderful shingle mill and lumber yard, below him, down by the canal. As soon as he could run down the hill, at the age of three or four, he would go there and play with discarded shingles and chips, making plank roads or toy buildings for hours on end.

The shipyard workers and canal boatmen were a rough lot, ready for a brawl on Saturday nights, and uproarious at torchlight processions on election days or holidays. At five Alva knew by heart some of the boatmen’s songs, and he could lisp the verses of “Oh, for a life on the raging canawl!”16

His elder brother Pitt liked to draw and sketch. In imitation of him, Alva, at about five, drew little pictures of all the craft signs hung over the shops in the square of Milan. His mind was decidedly visual; in later years he always made sketches of the mechanical devices that he contrived.

During this period, toward the age of five or six, there was a whole phase of misadventures and scrapes such as the experiment with the barn. Once he fell into the canal and had to be fished out. On another occasion he disappeared into the pit of a grain elevator and was almost smothered before he was rescued. He was nothing if not inquisitive.

With his round face and wide, well-formed chin, Tom Edison was an attractive-looking boy and was characterized by one of his cousins, Nancy Elliott, as being really “a good child most of the time,” but very headstrong and willful when he could not have his way. Nancy, at thirteen, acted as his “nanny” and remembered “having spanked him many a time and spanked him hard.”17 His mother also believed that the rod must not be spared. Edison himself later testified that his mother kept a birch switch handy for him behind the old Seth Thomas clock in the living room, and that it had “the bark worn off.”

Down at the canal basin there was the big steam-driven flour mill of an eccentric Yankee named Sam Winchester. Often the small Edison boy would be found with his nose pressed against the back window of Winchester’s shop watching the strange things being done there. His father scolded him severely for hanging about that place (as the story has come from his sister) and spanked him well for going there again after being warned not to do so. The mysterious Winchester (“The Mad Miller of Milan”) was not grinding flour, but was constructing a passenger balloon. The hydrogen he had used for this purpose had burned down his first flour mill. The boy Tom Edison knew about these experiments and about Winchester’s first, abortive attempt at flight. Some years later, during a second trial, Mr. Winchester managed to ascend into the air, then was wafted slowly in the direction of Lake Erie, never to be seen again.18

Finally there was one tragic accident in which the boy was involved when he was but five, or at most six years old, that deeply troubled Edison’s parents and that he himself never forgot. He recalled the whole affair in notes written long afterward, and with remarkable detachment:

When I was a small boy at Milan, and about five years old, I and the son of the proprietor of the largest store in the town, whose age was about the same as mine, went down in a gully in the outskirts of the town to swim in a small creek. After playing in the water a while, the boy with me disappeared in the creek. I waited around for him to come up but as it was getting dark I concluded to wait no longer and went home. Some time in the night I was awakened and asked about the boy. It seems the whole town was out with lanterns and had heard that I was last seen with him. I told them how I had waited and waited, etc. They went to the creek and pulled out his body.19

In recalling the strange adventure more than fifty years afterward, Edison showed that it had left an ineradicable impression on him, and “told all the circumstances... with a sense of being in some way implicated.”20

Why had he not called for help? Why had he said nothing on returning home? A country boy knew what drowning meant. Was he silent because he felt guilty and feared that, as usual after some mischance, he would be censured and beaten? His parents — his father being usually the more impatient one — could not help showing their distress at his “strange” behavior, so unlike that of other boys. Was this boy “without feelings,” as was sometimes said of him? Doubtless they applied the switch again, though whipping did no good. Frequent punishments only reflected poor adjustment between the child and his well-intentioned family, a recurrent failure of understanding and communication between them. The boy could not but sense his father’s continuing disappointment and disapproval of him and feel, though dimly, the weight of this.

2

What doom, what blight suddenly fell upon the future metropolis that was Milan, Ohio, the self-proclaimed “Odessa” of our Great Lakes? Today the Huron Canal is a morass, a mud-filled depression, and Milan would be like one of the ghosts towns left by the sudden veering of America’s commerce, had she not become a suburban backwater of Norwalk, now a big industrial city, then merely a sister village.

What happened, simply, was that the lake shore railroad came in 1853, but bypassed Milan and ran instead through Norwalk to Toledo. The too canny fathers of Milan who owned its canal had willed that things should be this way. When offered shares of stock and a station on the projected rail line in return for free right of way, they had stoutly refused to grant access to their port. They had no faith in those little steam-driven trains that rattled along iron-plated tracks of wood; they trusted instead in the economy of their canal and its favored position. The consequence was that commercial traffic followed the line of the railroad and was diverted from Milan, which eventually lost 80 per cent of its population.

It was the reverse of the recurrent American dream of great fortune to be won in a few years from some strategic ground site. Bad luck confounded the perennial optimist and hopeful speculator Sam Edison, who held land, a business establishment, and a house in an area where values were rapidly sinking. Yesterday he was well-to-do; today he was virtually a poor man, though consoling himself with the hope that by moving on he would find new fortune elsewhere.

Sam Edison had initiative, to be sure, and was ever alert for new opportunities all about him. Undoubtedly America was “built up” mainly by pioneers who were as sanguine and as luckless as Sam, and who were forever hunting for that “corner” in a future Chicago, or that mountain of coal, that somehow eluded them.

As Thomas Edison said in later years, there was “a collapse of the family fortunes,” caused by the reduction of canal tariffs at Milan in competition with the railroad and a depression in the town that “undermined the social standing of Samuel Edison, forcing him to leave his picturesque home and begin his life anew... This transpired in the year 1854.”21

Once more the nomadic Edisons were on the move, by train and carriage to Detroit and thence by a dainty little paddle ship, The Ruby, that bore them smoothly up the St. Clair River to Port Huron, Michigan, where they were to settle. It was late spring, the weather sunny and calm, and the scene was full of color, as a young neighbor who accompanied the Edisons described it. To the delight of Alva and his brother and sister, there were not only sailing craft and small lake steamers of every kind all around them, but Indians in feathers and beads, darting their canoes in and out of the ship’s course. Along the shore of the blue St. Clair River the Edison children could see smoke rising from the campfires of Indians still remaining in the vicinity.22

In the 1840s and 1850s, after the earlier waves of migration to Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois, had come the “Michigan fever” that drew many thousands of settlers to this region. It boasted not only its great forests, but iron, copper, and salt deposits. In this era the population doubled every ten years; land-boomers were confidently selecting future “lake cities” for exploitation. Such was Port Huron, where Sam Edison had first entered the United States; it was now a small town of four thousand at the entrance to Lake Huron from the St. Clair River, and hence commanding the rising traffic to the upper lakes. What was more, Sam Edison had learned that a railroad was being extended northward from Detroit some sixty miles to Port Huron, while a Canadian line, building eastward, would connect with the railway in Michigan by a ferry across the St. Clair at this same site.

Their new home was situated at Fort Gratiot, once a French trading post, now a United States Army base, at the northern outskirts of the town. Formerly the home of the purveyor to the military post, it was a large and solidly built house with columned balconies, set in a grove of pine trees adjacent to the parade grounds. From its big windows there were fine views over the river and lake. The rooms were spacious, and there were four huge fireplaces; the grounds, ten acres in extent, included an orchard, a large vegetable garden, and several outbuildings. There was only one thing wrong with this fine dwelling: the Edisons no longer owned their home, but rented it. Sam Edison used his remaining capital to engage in the lumber, grain, and feed trade.

He liked having more than one iron in the fire. One of his ventures at this period, that showed his taste for innovation, was to build a wooden observation tower, one hundred feet high, overlooking the surrounding bodies of water and their curving, wooded shore line. Visitors were to be charged a fee of twenty-five cents for the privilege of climbing its many stairs and peering through an old telescope on the top platform. Here the youngest Edison often played by himself; as time went on, he also acted as gatekeeper, collecting the tolls paid by occasional tourists. At first so few came that no more than three dollars was collected in a whole summer. Later the new railroad brought hundreds of excursioners; but the observation tower (called Sam Edison’s Tower of Babel) soon lost its novelty and was neglected, until it finally fell to the ground. The father, by then, had turned his restless mind to other schemes that were scarcely more profitable.

As the Edison fortunes declined, for Sam was no steady provider, his wife emerged as the real head and front of the family. It was she who worked with a compulsive energy, cooking and weaving, sewing and crocheting. It was she who struggled to keep the family afloat, with the aid of her children, and it was she who educated her youngest son.

On their arrival at Port Huron, Thomas Alva fell seriously ill of scarlet fever; the Edison family also suffered greatly from respiratory diseases for which they used to dose themselves with ineffective patent medicines. For this or other reasons the boy’s entrance into grammar school had been postponed. In the autumn of 1855, when he was more than eight years old, he was finally enrolled as a pupil in the one-room school of the Reverend G. B. Engle. Mr. Engle, it is related, liked to implant his lessons in his pupils’ minds with the help of a leather strap; his wife, who aided in the work of instruction, was said to be even harsher in her methods. It is not surprising, therefore, that the Edison boy, who had been growing up according to his own will, as a sort of child of nature, proved to be somewhat difficult in the classroom, his mind apparently refusing the lessons offered in such form. He said:

I remember I used never to be able to get along at school. I was always at the foot of the class. I used to feel that the teachers did not sympathize with me, and that my father thought I was stupid...23

After he had been at the school about three months, he overheard the schoolmaster one day saying of him that his mind was “addled.” In an outburst of temper, Tom Edison stormed out of the schoolroom and ran home, refusing to return.

The next morning his mother came with the boy to see the schoolmaster, and an angry discussion followed. Her son backward? She considered him nothing of the sort and believed she ought to know, having taught many children herself in her youth. The upshot was that she removed the boy from school and declared that she would instruct him herself.

The schooling received from the Engles, according to Edison’s later recollections, was utterly “repulsive” — everything was forced on him; it was impossible to observe and learn the processes of nature by description, or the English alphabet and arithmetic only by rote. For him it was always necessary to observe with his own eyes, to “do things” or “make things” himself. To see for himself, to test things himself, he said, “for one instant, was better than learning about something he had never seen for two hours...”24

The legend has come down to us, through Edison and his family, that it was because of the inadequacy of the teacher, and in the interests of the boy’s education, that his mother decided to keep him at home and instruct him privately. Some added facts, however, have come to light recently, showing that his father was either disappointed in his son and therefore reluctant to pay the small school fees, or was unable to pay them. Thirty years afterward, the schoolmaster, having heard a good deal about the later career of his “addled” pupil, wrote him:

Indianapolis, Ind.

August 13, 1885

Dear Sir:

You will remember that some years ago you attended school under my direction (and my wife’s) at Port Huron. Your father, not being very flush with money, I did not urge him to pay the school bill. I am now almost seventy-seven years old, and am on the retired clergy list. And as you have now a large income I thought perhaps you would be glad to render me a little aid.

Truly yours,

Reverend G. B. Engle25

Edison responded with a check for twenty-five dollars, liberal enough in view of his unhappy memories of school and teacher.

Unlike the other boys in the little town, he stayed at home all day, and every morning, after his mother’s preliminary housework was done, she called him to his lessons and taught him his reading, writing, and arithmetic. The affection between mother and son was very strong, especially in these years, when Nancy Edison’s relations with her husband grew less happy. Her son had the impression she kept him at home by her side, as he said, partly “because she loved his very presence.” She taught him not only the three R’s, but “the love and purpose of learning... she implanted in his mind the love of learning.”26

In summer, as in winter, the program of instruction went forward. According to the reminiscence of a Port Huron playmate:

A few of us boys were playing in front of the Edison house one day with Al in our midst, when a lady appeared on the porch, a nice, friendly-looking one, plainly dressed and wearing a lace cap in the style of that period. Looking over the group for a moment, she called out: “Thomas Alva, come in now for your lessons.” The boy obeyed without a word; as he went we looked at him in a sort of commiserating way. It seemed rather hard to be called away from the diversions of a beautiful summer day to study dry lessons; and besides it was vacation time!27

To a modern educator Alva would surely have been a rewarding subject for study. Among prodigies there are both the precocious ones and those whose minds grow slowly or “unevenly” in boyhood — Isaac Newton’s, for instance, as well as Thomas Alva’s. In this case, the remarkable mother gave the boy sympathetic understanding that bred confidence. She avoided forcing or prodding and made an effort to engage his interest by reading him works of good literature and history that she had learned to love — and she was said to have been a fine reader. In this sense she was out of the ordinary. In the fifties, most literate women had magazines like Godey’s Lady’s Book as their favorite reading; and if they read to their children it was from the Rollo Books, or Peter Parley’s Tales of the Sun, Moon and Stars. But Nancy Edison had superior taste. Believing that her son, far from being dull-witted, had unusual reasoning powers, she read to him from such books as Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Hume’s History of England, or Sears’s History of the World; also literary classics ranging from Shakespeare to Dickens. Instead of being bored by these works of serious literature, he grew fascinated and at nine was inspired to read such books himself. While immature and ill-disciplined in some respects, he was advanced in others and soon became a very rapid reader.

Nancy Edison, however, could scarcely have been a wholly adequate teacher, her experience having been limited to teaching in a small Canadian village for a year or so before her marriage at the age of eighteen. Her son never learned how to spell; up to the time of his manhood his grammar and syntax were appalling. We see then, as did the Reverend Mr. Engle, that he was indeed hard to teach. Whatever he learned, he learned in his own way. In fact, though his mother inspired him, no one ever taught him anything; he taught himself.28

On the other hand, his mother could not but notice that in some of the odd or funny things the boy said he showed a high imagination, sometimes expressing ideas or abstract numbers by some apt visual image. Weighing himself on a scale at the age of ten he is remembered to have exclaimed: “Mother, I’m a bushel of wheat now, I weigh eighty pounds!”

Nancy Edison also sensed, or discovered by chance, the real direction of her son’s interests; for one day she brought forth an elementary book of physical science, R. G. Parker’s School of Natural Philosophy, which described and illustrated various scientific experiments that could be performed at home. Now his mother found that the boy had truly caught fire. This was “the first book in science I read when a boy, nine years old, the first I could understand,” he later said. Here, learning became a “game” that he loved. He read and tested out every experiment in Parker; then his mother obtained for him an old Dictionary of Science, and he went to work on that. He was now ten and formed a boyish passion for chemistry, gathering together whole collections of chemicals in bottles or jars, which he ranged on shelves in his room. All his pocket money went for chemicals purchased at the pharmacist’s and for scraps of metal and wire.

Thus his mother had accomplished that which all truly great teachers do for their pupils: she brought him to the stage of learning things for himself, learning that which most amused and interested him, and she encouraged him to go on in that path. It was the very best thing she could have done for this singular boy.

“My mother was the making of me,” he said afterward. “She understood me; she let me follow my bent.”29

The marriage of experimental activity and knowledge thus came early in life for Thomas Alva. Some of his first “experiments,” to be sure, were conceived out of nothing more than sheer mischief. Having read something of Benjamin Franklin’s discoveries in static electricity he tried the trick of vigorously rubbing the fur of two big tomcats, whose tails he had attached to wires, the only result being that he was unmercifully clawed. Pondering the problem of balloons that were able to ascend in the air because of the volatile gas in them — like Mr. Winchester’s in Milan — he administered a large quantity of Seidlitz powder to his simple-minded playmate, Michael Oates, reasoning that the gas thus generated might set the boy flying through the air. The young Oates, however, became terribly sick to his stomach, and Alva was soundly spanked by his mother. It is noteworthy that when the Edison boy did have companions of his own age he would sometimes play the tyrant with them and they would be his submissive “slaves,” as was Oates — though bigger, and older than himself.

The chemicals in his bedroom were a “mess,” as his mother complained; the wet-cell batteries sometimes spilled sulphuric acid on furniture and floor. His mother, on such occasions — though ordinarily most affectionate — could show a warm temper, for the son said, “My mother’s ideas and mine differed at times, especially when I got experimenting and mussed up things.”30 He was therefore ordered to remove his jars to the cellar of the house. To keep others from using or tasting his chemicals he labeled all his bottles “Poison” — hardly scientific, but good insurance.

A corner of the cellar in the Port Huron house was Thomas A. Edison’s first laboratory. There, after the age of ten, he secluded himself, often all day long, absorbed in his study of simple chemicals and gases and in the design of his first homemade telegraph set. Other boys might play in the fields or fish in the river; but Tom Edison buried himself in his cellar laboratory, with his elementary manuals and his chemical and electrical outfits.

His father persisted in his disapproval of the boy’s subterranean devotions. He would sometimes offer Alva the bribe of a penny if he would read some book of serious literature. Thus, when he was twelve the boy read Tom Paine’s Age of Reason, at his father’s suggestion. “I can still remember the flash of enlightenment that shone from his pages,” he wrote long afterward.31 The pennies, however, were saved and applied to the purchase of more powders and chemicals.

“Thomas Alva never had any boyhood days; his early amusements were steam engines and mechanical forces,” his father commented. On another occasion, in later years, Sam Edison said of his son, “He spent the greater part of his time in the cellar. He did not share to any extent the sports of his neighborhood. He never knew a real boyhood like other boys.”32 Actually, through his own kind of intellectual play, the Edison boy was intensely happy — though his father could not understand this. He was also, despite his steam engine models, very much a boy.

Up to the age of fourteen, and even afterward, he continued to show such high spirits that it was hard to hold him down. Though he was older, he could not resist playing practical jokes on people, even at some risk to himself; and so his father continued the whippings from time to time. In 1861, for example, a whole regiment of volunteer troops was stationed at the Fort Gratiot reservation opposite the Edison home, for the Civil War had begun. The place was heavily guarded; there was much drilling and calling of orders between guards and sentinels day and night. Late one night, Tom and another boy had the idea of having some fun with the soldiers. Imitating their tones, Tom called out loudly for “Corporal of the Guard Number One,” then ran off in the darkness. The call was duly taken up by the sentinels and repeated, with resultant confusion. When the same trick was tried again the next night, the soldiers pursued the two boys. The other boy was caught, but Tom hid himself in a barrel of apples in the cellar, while the soldiers, having awakened his father, searched for him with lanterns in vain. When all was quiet again, Tom stole back to his room.

“The next morning I was found in bed, and received a good switching on the legs from my father...” he related.33

Bouts of horseplay alternated with prolonged sessions in elementary physical science and chemistry below stairs. Accidents occurred, the muffled sounds of explosions sometimes reaching the parents from the cellar. “He will blow us all up!” the anxious father would exclaim.34

But his mother remained stanch in his defense. “Let him be,” she said; “Al knows what he’s about.”

Above all things, he loved to work over models of the telegraph; as a boy, he was fascinated with the whole idea of electricity, introduced into practical, everyday usage not long before his time by Samuel F. B. Morse. To be sure, it was the earlier experiments and discoveries of the learned American physicist, Joseph Henry, in the field of electromagnetism which had opened the way to Morse’s practical invention. That was a fabulous invention in its day. When Morse first exhibited his instrument in New York in 1838, great crowds flocked together in the streets nearby and, in good American fashion, begged to be allowed to look upon it, “declaring they would not say a word or stir, and didn’t care whether they understood or not, only they wanted to say they had seen it.”35 By 1848 the telegraph flashed intelligence over a network extending from New York and Boston, via Albany, as far as Chicago. As a boy, Edison, like many other Americans, followed with intense excitement news of the pioneering bands of young telegraphers who extended their long lines of wire across the great prairies, over the Indian-infested deserts and the mountains, to California — so that the continent was first spanned, not by the railroad, but by the telegraph — in 1861, during the opening months of the Civil War.

What was electricity, Tom Edison kept asking people. A Scotsman, who was a station agent on the new railway that came to Port Huron, finally explained to him in apt words that “it was like a long dog with its tail in Scotland and its head in London. When you pulled its tail in Edinburgh it barked in London.”

By the middle of the century hundreds of youths who dreamed of becoming telegraphers could be found almost everywhere around the country, pottering with homemade wet cells and crude sounders of their own device. It was in no way remarkable that Edison, at the age of eleven, had his own homemade telegraph set and had begun to practice the Morse code. Seventy years later he would recall how he had constructed a crude set after having read a popular handbook of experiments in physical science.

I built a telegraph wire between our houses... separated by woods. The wire was that used for suspending stove pipes, the insulators were small bottles pegged on ten-penny nails driven into the trees. It worked fine.36

The Edison of 1857 or 1858, whom we glimpse for a moment running barefoot through the woods to string up his homemade telegraph line, is decidedly an American type — the mechanically ingenious boy, on the farm or in a small town, growing up with a passion for “whittling” or “tinkering.” Like the Yankee inventors of the preceding generations, Edison in boyhood cared little for lessons in reading and writing, if he could but “play” with his telegraphs, batteries, and chemicals; and like the others of his kind, he was considered “wayward,” or at least “different from other boys,” by his parents. At an early age he became absorbed, to the exclusion of everything else, in learning all that he could of the comparatively new electrical science, from his own observation and by making or trying things with his own hands.

In working with his first crude telegraph made of scrap metal, Edison the boy approached, unwittingly, the main stream of electrical experiment since the days of Benjamin Franklin.

More than pocket money, however, was needed for his expanding “laboratory” in the cellar. He was now bent on making a proper Morse sending and receiving set of his own, and these were hard times for the Edisons. At the age of eleven Tom, with the help of the boy Michael Oates, who did chores around the Edison place, embarked upon his first commercial venture. The two boys laid out a large market garden and tried raising vegetables. A horse and cart were hired, and soon Tom was driving about the town trucking onions, lettuce, cabbages, and peas. Evidently the business was sponsored and supervised by his mother; the first summer’s harvest, so he claimed, netted all of “two or three hundred dollars.” Was he a merchant prince in embryo? However, he quickly tired of this work, as he says, for “hoeing corn in a hot sun is unattractive...”37

The big event for Port Huron in 1859 was the coming of the railroad, extending northward from Detroit. Those iron and brass locomotives, those brightly painted carriages held an irresistible attraction for the young Edison. Even before the railway was formally opened at Port Huron, he had learned that there would be a job on the daily train for a newsboy, who, though receiving no regular wage, would have the concession of the “candy butcher” to purvey food and sweets to the passengers. He was only twelve, and small for this work. Though his mother strongly objected to the idea, their situation, as his father admitted, was such that no schooling for the boy could be considered, and Tom was faced by “the early necessity of gaming his own living.”38 In discussing the matter, he promised that during the long layover of the daily train at Detroit, he would use his time to read books; he would also have money with which to continue his scientific self-education.

It has been related that “there was no real need” for him to go to work at twelve, that his parents were not poor, but were, in truth, “well-to-do.” He is usually pictured as precocious in his desire to get into the workaday world and make his own way. The evidence, however, points to the impoverishment of Sam Edison, who at this period, it was said, “thought nothing of walking sixty-three miles to Detroit.” His business affairs evidently allowed him much idle time, but no horse and carriage. The son remembered that he had to use “great persistence” in bringing his mother around to his idea. It was the father who selected the job for his son and negotiated with the railroad people for his employment.39 In his autobiographical notes (written in 1885), Edison says that at this time he was “poorly dressed”; and also that, “Being poor, I already knew that money is a valuable thing.”

An early photograph, dated 1861, shows him in a worn old cap and roughly clad, yet most attractive and intelligent-looking, with his fine brow, his wide jaws, and his big smile. The local railroad officials, at any rate, gave him the job.

Thomas Alva Edison at the age of fourteen.

3

The “mixed train” of passengers and freight, with a great huffing and puffing from its tall stack, departed from Port Huron daily at 7 a.m. on a journey of more than three hours to Detroit, waited over there most of the day, and returned again to Port Huron at 9:30 p.m. As the train pulled out of the station, a lively urchin, carrying a basket almost bigger than himself, quickly scrambled on board and then made his way through the carriages, calling out: “Newspapers, apples, sandwiches, molasses, peanuts!”

The landscape raced by at the exhilarating speed of thirty miles an hour. There was an ever-varied scene and always the changing crowds of passengers — farmers, workers, immigrants, and sometimes elegant tourists from far-off places. Tom Edison was a cheeky fellow and at first thoroughly enjoyed this new life of movement and active commerce with all sorts of people. In those days he had, as he himself said afterward, a sort of “monumental nerve.” Not only did he dispense a stock of candies along with newspapers and magazines, but he also won permission from the conductor to store a quantity of fresh butter, berries, vegetables and fruit in the baggage car of the train, which thus traveled as free freight and which he disposed of at retail along the route.

The report of an old newsdealer of Detroit shows that he was an honest boy who always did business for cash and paid promptly. Also that he would not brook dishonesty in others. Sometimes he would seem so distracted, thinking of one of his elementary experiments, or reading a book, that when a boy who shared his newspaper depot at Port Huron came to give him money, Tom would put it in his pocket without counting it. But when he found that the boy had not been honest with him, he closed up that newspaper depot rather than have anything more to do with the fellow.

Yet there was also the irrepressible spirit of mischief in him. On being questioned, in later years, as to what kind of trainboy he had been, he confessed that he was the sort who “sold figs in boxes with bottoms an inch thick.”

He told afterward of his adventures with a zest that showed that inventiveness with him was not confined only to mechanical work. In 1860, just before the Civil War began, he recalled that two elegant young men from the South, accompanied by a colored servant no less elegant, boarded the train at Detroit; on his approaching them, one of them asked, “Papers?” then took all of Tom’s newspapers and threw them out the window, saying to his colored man in haughty tones, “Nicodemus, pay this boy.” Thomas Alva then brought them quantities of magazines, food, and popcorn; all were disposed of in the same way, until his whole stock was gone, and he had been paid off most liberally. “Finally,” he said, “I pulled off my coat, hat and shoes, and laid them out.” For this too he was given a high price, while the other passengers roared with laughter at the barefoot boy’s antics. Then the Southern swell cried out, “Nicodemus, throw the boy out too!” But Tom Edison ran away.40

At a tender age he learned about life from the talk of the railroad workers, farm hands, and immigrants. In the 1850s, child labor was widespread; young boys and girls went to work at an early age in the big towns, as in New York, where one could see girls of ten to twelve sweeping the crossings of main thoroughfares so that ladies and gentlemen might pass dry-shod over the dung-ridden places. So Tom Edison worked on the railroad at twelve, returned home long after dark, and gave his mother a dollar a day from his earnings.

There was so much he could learn merely by using his keen eyes. At the railroad yard in Detroit he could watch the men switching cars, or repairing valves and steam boilers. Waiting in the station he observed closely the operations of telegraphers, then beginning to signal train movements between stations.

In Detroit, already a city of over 25,000, he was left to his own devices all day, wandering about with a little money to spend on equipment or books, talking with men in machine shops, some of them even full-grown inventors, like young George Pullman, then making some of his first railway carriages in a small shop in that city.

“The happiest time of my life was when I was twelve years old,” he said afterward. “I was just old enough to have a good time in the world, but not old enough to understand any of its troubles.”41

He was away from home, he was away from his father, he was on his own. His home, moreover, was hardly a happy place nowadays.

After he had been working on the railroad for a year or so, he thought of a way of occupying his leisure time during the layover in Detroit. Since the baggage and mail car up forward in the train had a good deal of empty space, he had the idea of installing his little cellar laboratory at one end of it. The trainman was won to compliance; soon Tom had transported his stock of bottles, test tubes, and batteries, and ranged them neatly on shelves that were fitted to the back wall of the car. It was said that George Pullman made up the railed shelving that would hold those jars and bottles safely against the bouncing of the train. This was, no doubt, the world’s first mobile chemical laboratory, probably installed some time in 1861.

There he was at twelve to thirteen, adrift on the train like Huckleberry Finn on his raft on the broad Mississippi. It makes a legendary picture that is touched with the insouciant charm of the mid-nineteenth-century era in America. Tom Edison, moreover, restlessly inventive in his pranks as in his elementary mechanical experiments, may also be represented as The Eternal American Boy, with much of the audacity and the imagination of Huck Finn. He too seemed determined to leave home and make his way along the “river of life.”

The real picture, however, is not always so pleasing. The hours away from home were long and wearying; leaving at dawn, the young boy would return at ten or eleven at night. There were the sudden blows of life to be borne, even danger to be faced as bravely as he could, at twelve and thirteen. He had courage to spare, though like the old pioneer, Sam Houston, he used to say that he knew no fear save of “the black dark night.” In illustration of the rational way in which he tried to conquer his own nerves and imaginary fears, he would tell the story of how Houston, on being accosted in a Texas cypress swamp by a sheeted figure appearing from behind a tree, shouted, “If you are a man you can’t hurt me, and if you are a ghost you don’t want to hurt me. But if you are the devil come home with me; I married your sister!”

So Tom Edison, driving home from the station toward eleven at night with his horse and cart and leftover newspapers, used to become utterly terrified when he reached a stretch of deep dark woods, containing a soldiers’ graveyard. His nerves on edge, he would shut his eyes, whip up the horse, and go thundering past that graveyard, while his heart leaped in his throat. But after many weeks of such anxious flight through the dark thicket, he found that nothing happened; the fear of graveyards finally left his system.

One night, while he was still a trainboy, he was called to the office of a steamship company at Port Huron and given an errand which, as he was told, was of the utmost urgency. A steamboat captain had suddenly died; his big ship, lacking a navigator, was held idle in the port; therefore the Edison boy was to go at once and fetch a certain ship captain who lived in retirement on a timberland property about fourteen miles from the nearest railroad station, at Ridgway, Michigan. There was no other means of reaching the man quickly save on foot; in compensation for that nocturnal journey over the forest trails Edison was offered a generous fee of fifteen dollars.

With another small boy, who had been persuaded to accompany him on the all-night hike — by the offer of sharing his earnings — Tom Edison started off at 8:30 p.m. A heavy rain was falling, and the night was black as ink. They had lanterns with them, but the trail lay through rough, cut-over land and they fell often; every stump looked to them like a Michigan bear. One lantern went out, then the other; after that the imaginative Tom was certain he could hear the movement of wild beasts all about them. When a good many miles had been covered they were utterly spent, and giving themselves up for lost, according to Edison’s account, “we leaned up against a tree and cried.”

Nonetheless, Tom Edison forced himself to go on and on, with his companion who was even weaker than himself, so that they might reach the old captain in time. Their eyes gradually becoming accustomed to the dark, they managed to stumble along for the rest of the fourteen miles of corduroy road. At the first gleam of dawn they entered the captain’s yard and delivered the message. “In my whole life I never spent such a night of horror.”42

4

Then, as if to make the conditions of life all the harder for him, there came to him the cruel affliction of deafness. Its beginning is placed at the time when he was about twelve, shortly after he began working on the railroad. Long after the event he gave conflicting accounts of how this misfortune came to him “suddenly.” The earlier stories of his boyhood, done long ago in the Horatio Alger style, have much pathos but are misleading. From the symptoms of his deafness, as described by himself and others as well, it seems to have been traceable to the aftereffects of scarlatina suffered in childhood, and to have developed through periodic infection of the middle ear that was unattended.

In the earlier tales of how his deafness arose he is described as having been busy one day in his baggage-car laboratory. In those times the iron-plated tracks were so unpredictable that they sometimes curled up and pierced the floors — and seats! — of passing cars. At all events, the train suddenly gave a violent lurch, and a jar holding some sticks of phosphorus in water fell from the shelves to the floor; on being uncovered and exposed to the air the phosphorus soon ignited with a startling white light and burst into flames. The wooden floor of the car took fire, while the boy struggled vainly to smother the flames. The conductor, one Alexander Stevenson, sometimes described as a “dour Scot,” came forward in time to douse the little fire. Then, it is related, he lost his head, “cursed Edison roundly and boxed his ears” with such “brutal blows” that the boy soon afterward became deaf. “When a few minutes later the train stopped at Smith’s Creek station, the conductor threw the boy overboard, and after him his whole laboratory and printing press.” Tom Edison was left weeping beside the railroad track, and permanently injured as well.

The details of this story, however — and it has become a legend — are broadly inaccurate. Edison himself tried to recapitulate things toward the end of his life, so as to correct the more romanticized accounts of his boyhood misfortunes. According to these later recollections, he was delayed in getting to the train one morning; it was already leaving the station. “I was trying to climb into the freight car with both arms full of heavy bundles of papers... I ran after it and caught the rear step, hardly able to lift myself. A trainman reached over and grabbed me by the ears and lifted me... I felt something snap inside my head, and the deafness started from that time and has progressed ever since.” He remembered that at first he could hear only “a few words now and then,” after which he “settled down to a steady deafness.”43

In retelling the story to his intimates of later years, he also roundly declared that the ear-boxing incident never happened. “If it was that man who lifted me by the ears who injured me, he did it to save my life.”44 In truth he considered that Alexander Stevenson, the conductor, had been his benefactor, for they corresponded on friendly terms afterward.45

It seems that Stevenson, far from showing cruelty, took a fancy to the odd but resourceful trainboy; he had even taken some liberties with the rules of the railroad in admitting Alva’s laboratory to a corner of the baggage car. “The telegraphers and trainmen were a good-natured lot of men and kind to me,” Edison himself said.46 The accidental fire, which did in fact take place some time in 1862, made Stevenson determined to remove the boy’s chemicals and Voltaic jars from the train. The ejection of Tom Edison’s laboratory-on-wheels, however, evidently did not take place until more than two years after he first felt himself growing deaf.47

He was, thus, permanently disabled when not yet thirteen. If there had been any thought of returning him to school for higher education or for some formal training, it must now be put aside, for he would not hear his teachers. The prospects for a handicapped boy of a poor family were certainly not good.

Nevertheless, he was able to go on working as a trainboy. When the train was in motion he could hear well enough above the roar of the locomotive and the clanking of the wheels, since everyone in a noisy car tends to raise his voice to a shout. “While the train was roaring at its loudest I would hear women telling secrets to one another. But during the stops, while those nearest to me conversed in ordinary tones, I could hear nothing... Doctors could do nothing for me.”48

It was his habit to make light of his misfortunes. The loss of one of his most vital senses (as with his lack of schooling) was sometimes represented by him as an advantage or an “asset.” He was spared a great deal of the vexation suffered by persons of normal hearing and, so, was the more able to concentrate his thoughts, or think something through without interruption. The uproar in the streets in big towns did not disturb him. But whatever he may have said on this score, his intimates declared that he had never really been glad that he was deaf.

In the privacy of his brief diary he wrote truthfully, years later, these words of infinite sadness: “I haven’t heard a bird sing since I was twelve years old.”

That the loss of hearing brought him, in effect, to an important turning point in his life was true. He tended to be more solitary and shy; became more serious and reflective; drove himself to more sustained efforts at reading and study, which had been carried on lately, for a year or two, in a rather desultory fashion. He had been only “playing,” hitherto, with his books and his “experiments.” Now he put forth tremendous efforts at self-education, for he had absolutely to learn everything for himself. And whereas he had earlier, by some boyish traits, appeared immature or lighthearted, he now seemed serious, or rather old for his years, the habit of meditation becoming more fixed.

It was then, one might more readily believe, after his hearing had become impaired, that he carried the paraphernalia of his little cellar laboratory at Port Huron into the baggage car of his train. It was then, while the car stood in the yard, that he came to enjoy spending so many long hours alone, wholly lost in his elementary experiments with wet cells and stovepipe wire and his first crude telegraph instruments.

As he has related, he felt himself “shut off” from “the particular kind of social intercourse that is small talk... all the foolish conversation and meaningless sound that normal people hear... Deafness probably drove me to reading.”

In Detroit, during the hours of layover, he found his way to the public library. Formerly the reading room of the Young Men’s Association, it was reorganized in 1862 as the Detroit Free Library. That year Thomas A. Edison, then fifteen, became one of its earliest members, being given a card numbered 33 and paying the substantial fee of two dollars for it.49 He relates:

My refuge was the Detroit Public Library. I started with the first book on the bottom shelf and went through the lot, one by one. I didn’t read a few books. I read the library. Then I got a collection called The Penny Library Encyclopedia and read that through... I read Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy — pretty heavy reading for a youngster. It might have been if I hadn’t been taught by my deafness that I could enjoy any good literature... Following the Anatomy came Newton’s Principles...50

He had formerly read at random books of history, literature, and elementary science, under his mother’s tutelage, in an indiscriminate fashion. Now, going it alone, he carried on a sort of frontal attack on books of every sort. Robert Burton, the old seventeenth-century ecclesiastic, on one day, Isaac Newton the next! The title and theme of Burton’s whimsical work must have appealed to Tom Edison’s mood at this stage; Burton, too, felt himself isolated, sang of his loneliness and poverty, and also of his dreams, of his will to happiness, though in the simplest and humblest circumstances.

In the same way, Edison vastly enjoyed reading Victor Hugo’s romantic epic Les Misérables, just then translated into English and being very widely read in the United States. The story of the lost children, such as Gavroche, and the figure of the noblehearted ex-convict, Jean Valjean (also an “outsider”), appealed to him strongly. In his youth he spoke of Hugo with such enthusiasm that his companions sometimes called him “Victor Hugo” Edison.

During this period of fermentation, of intellectual excitement and mental growth, he tackled Newton’s Principles, whose importance he suspected. He was then fifteen — not nine or ten as has been said — but was wholly unprepared to plunge into what he called a “wilderness of mathematics.” Without anyone to aid him, he kept at the Principles for long hours, until he became baffled and bewildered and threw it aside. He said later, “It gave me a distaste for mathematics from which I have never recovered.”

A thousand pities that the young Edison, with his lively imagination and mind voracious for knowledge, was given so little informed counsel and, so, began his studies without the discipline that formal instruction might have imposed. For him there were no devoted teachers who could communicate an interest in the beautiful mathematical constructions of an Isaac Newton — as was done in England for a James Clerk Maxwell or a Lord Kelvin in early youth.

Making his way alone, as well as he could, through masses of books and manuals, he turned to more practical treatises by men of narrower scope. To this period of intensive self-education belongs his reading of books like Karl Fresenius’s Chemical Analysis and Andrew Ure’s treatise on practical mechanics, which he was able to master unaided. In Ure’s Arts, Manufactures, and Mines, published in 1856, he read passages ridiculing the “academical philosophers” (such as Newton), who were said to be “engrossed with barren syllogisms, or equational theorems... and disdained to soil their hands with those handicraft operations at which all improvements in the arts must necessarily begin.”51 Ure urged that it was these “men of speculative science” who must be shunned, holding that they neglected for sixty years the steam engine of Newcomen, “until the artisan James Watt transformed it into an automatic prodigy.” These were lessons that appealed not only to the public of Victorian England but also to that of “practical, money-making” America.

At an impressionable age, Tom Edison’s reading and thinking, pursued alone, without guidance, disposed him to avoid the example of a Newton and follow that of a James Watt or of a factory mechanic like Arkwright.

5

“In my isolation (insulation) I had time to think things out,” Edison said of this period.

There was the inconvenience of continued poverty among other disadvantages he suffered. What was to be done about this? He said:

At the beginning of the Civil War I was slaving late and early to sell newspapers; but to tell the truth I was not making a fortune. I worked on so small a margin that I had to be mighty careful not to overload myself with papers.52

The years when he rode back and forth on the Grand Trunk Railway coincided with some of the most dramatic events in American history, to him but remote happenings. There was the insurrection and the hanging of John Brown, the election of Abraham Lincoln as President, the firing at Sumter, the opening of the Civil War. He had noticed, however, that when reports of a battle were printed, his newspapers sold faster than on other days, and then he could barely carry enough copies of the papers to the train. He therefore made it his practice to go to the composing room of the Detroit Free Press and inquire what the headlines were on the advance galley proofs for that day’s edition, so that he might better estimate his needs. Necessity and early experience in hawking produce had given him a shrewd commercial sense.

One day in April, 1862, the first accounts of an immense and sanguinary battle between the armies of Grant and Johnston at Shiloh reached the newspaper office by telegraph. Learning of this before the newspaper was out (and before the evening train left for Port Huron), the trainboy conceived the idea of a splendid little stroke of business for himself. The proofs he had seen showed that the Free Press would carry huge display heads announcing a battle in which 60,000 were then believed to have been killed and wounded!

Here was a chance for enormous sales, if only the people along the line could know what had happened. Suddenly an idea occurred to me. I rushed off to the telegraph operator and gravely made a proposition which he received just as gravely.

At Edison’s request, a short bulletin was to be wired by the Detroit train dispatcher to the railroad stations along the road to Port Huron, and the telegraphers there would be asked to chalk them up on bulletin boards in the depots, before the train arrived. For this free telegraph service Tom Edison would pay the friendly Detroit telegrapher with gifts of some merchandise, newspapers, and magazine subscriptions. Thus forearmed, the boy went to the office of the newspaper’s managing editor, Wilbur F. Storey, to ask for a thousand copies of the paper, an uncommonly large assignment, since usually he took but two hundred, and he asked for this on credit. He had boldly marched up to Mr. Storey himself, because the man in charge of distribution had rebuffed him. The managing editor examined the ragged boy whose expression, however, was resolute enough. “I was a pretty cheeky boy, and felt desperate,” he himself recalled later. The authorization was given him and, with the help of another boy, he lugged huge bundles of the newspaper to the train and folded them up.

His device of having advance bulletins telegraphed and posted at the depots worked even better than he had hoped. In his own vivacious way Edison related:

When I got to the first station on the run... the platform was crowded with men and women. After one look at the crowd I raised the price to ten cents. I sold thirty-five papers. At Mount Clemens, where I usually sold six papers, the crowd was there too... I raised the price from ten cents to fifteen... It had been my practice at Port Huron to jump from the train about one quarter of a mile from the station where the train generally slackened speed. I had drawn several loads of sand to this point and had become quite expert. The little Dutch boy with the horse usually met me there. When the wagon approached the outskirts of town I was met by a large crowd. I then yelled: “Twenty-five cents, gentlemen — I haven’t enough to go around!”

The sale of the “extra” was held, as he recalled, in the vicinity of a Port Huron church where a prayer meeting was in progress. He yelled out his news. In a few moments “the prayer meeting was adjourned, the members came rushing out, bidding against each other for copies of the precious paper. If the way coin was produced is any indication, I should say that the deacon hadn’t passed the plate before I came along.”53

“It was then,” he added, “it struck me that the telegraph was just about the best thing going, for it was the notices on the bulletin board that had done the trick. I determined at once to become a telegrapher.”

It is noteworthy that one of the chief attractions of the telegraph for him was also connected with his bad hearing. With the telegraph he could hear. He relates, “... Thus early I had found that my deafness did not prevent me from hearing the clicking of a telegraph instrument. From the start I found that deafness was an advantage to a telegrapher. While I could hear unerringly the loud ticking of the instrument I could not hear other and perhaps distracting sounds...”

After learning all he could by studying the apparatus of the dispatching telegraphers at the railway stations, he had recently made an improved sending and receiving set of his own device. A young neighbor in Port Huron who helped him related:

He [Edison] was always tinkering with telegraphy and once rigged up a line from his home to mine, a block away. I could not receive very well, and sometimes I would come out and climb on the fence and halloo over to know what he said. That always angered him. He seemed to take it as a reflection on his telegraph.54

Later, when he was fifteen, he set out a longer line of stovepipe wire running about a half mile, strung out on trees, to the home of James Clancy, who sometimes helped him at news vending. On returning home, though it was 10 p.m., he would stay up and “play” for hours at sending and receiving messages. His father tried to drive him to bed; but Tom Edison, a sly one, knew ways of hoodwinking the old man.

His father, he had noticed, had formed a habit of reading (gratis) one of the unsold newspapers Tom usually brought back with him at night. The boy therefore took to coming home without any newspapers, reporting that business was humming nowadays. But, he said, there was his friend, Clancy, who had a newspaper that was ordered and paid for by his parents, and he, Tom could obtain the leading news stories by telegraphing him over their little private wire. The elder Edison, much intrigued by this scheme, thereafter permitted him to stay up and practice the Morse code till midnight, or even later. This arrangement was continued until a cow, wandering through the orchard one night, blundered into the low telegraph line and brought it down.

With the thought of possibly getting a job some day as a railroad mechanic, Edison, haunting the roundhouses, learned a good deal about the mechanism of steam locomotives and the working of fireboxes, valves and gears. One day a locomotive engineer, fatigued after a night of revelry, actually allowed him to drive one of the machines pulling a freight train while the older man took a nap. This locomotive, as Edison remembered, “had bright brass bands and beautifully painted woodwork and everything highly polished, as was the custom up to the time old Commodore Vanderbilt stopped it on his roads.” Mounted at the levers, Edison cautiously slowed the speed of the train to twelve miles, but before he had gone far a sudden spurt of damp black mud had blown out of the stack and covered part of that beautiful engine, including the boy driver. Stopping at the station where the firemen usually went out to oil the machine, Tom climbed upon the cowcatcher and tried to do likewise, by removing the oil cup on the steam chest. The steam rushed out with a tremendous blast almost hurling him to the ground. He had failed to notice that the driver always shut off steam when oiling was being done.

Somehow he managed to get the oil cup on again, and drove off even more slowly all the way to the junction. But just before he reached it another outpour of mud covered him and the entire engine, so that, as he pulled into the yard, everyone turned out to see him and laughed.

He soon learned that the eruptions of mud were caused by his carrying too much, rather than too little, water, so that it had passed over into the stack and washed out all the soot. “My powers of observation were very much improved after this occurrence,” he said.

At the beginning of 1862 he developed a sudden interest in the craft of printing, and thought for a while of becoming a journalist and starting his own newspaper. The important role played by the newspaper he sold every day had not failed to impress itself on him. With some money he managed to save at the time of Shiloh, he purchased a small secondhand press, together with some old type (three hundred pounds of it) found on the bargain counters of Detroit; in a short time he had taught himself to set type and run a hand press. Now, putting aside his chemicals, he undertook the venture of editing, printing, and selling a small local newspaper, which was produced in that same baggage car.

The Weekly Herald, written, printed, and published by Thomas Edison at the age of fourteen in a baggage car on the Grand Trunk Railroad.

The Weekly Herald, issuing from a branch of the Grand Trunk Railroad, at eight cents a copy, with a circulation of about four hundred, was said to have been the first newspaper in the world that was published on a train. It covered local news and gossip, reports of the railroad service, changes of schedule, and occasional bits of war news received over the wires almost before the regular newspapers had them. Certain of its editorial reflections were uncommonly philosophical for an editor-pressman of fifteen, as: “Reason, Justice, and Equity never had weight enough on the face of the earth to govern the councils of men.” (It sounded like something his skeptical father might have said.) In the next paragraph there might be the report that some station agent was the parent of a bouncing daughter of seven pounds; or that another had volunteered for war service. The style, grammar, and punctuation were haphazard, the spelling was phonetic, if not worse. An example:

ABOUT TO RETIRE

We were informed that Mr. Eden is about to retire from the Grand Trunk Company’s eating-house at Point Edwards... We are shure that he retires with the well wishes of the community at large.55

We applaud in the fifteen-year-old Edison his manual skill and his spirit of enterprise. But in almost every other line of his text occurred such errors of orthography as “valice,” or “villian,” or “oppisition,” which probably hampered the progress of his gazette.

The entrepreneur-editor of fifteen might have gone on to master the Queen’s English and, in time, become a great journalist, if not for an untoward incident that illustrated the serious hazards of this calling. An acquaintance of his, who helped print the Port Huron Commercial, after a while persuaded Edison to enlarge his newspaper, turn it into a medium of society news and personal gossip, and rename it Paul Pry. But one of its candid little stories, touching a local figure, proved to be so excessively candid that the victim vowed he would have vengeance. One day the embittered man sighted the young editor near the docks of Port Huron, laid violent hands on him, and threw him into the St. Clair River. Fortunately Tom was a strong swimmer; but after this immersion he rapidly lost interest in Paul Pry, which ceased publication.

An adventure of another kind, which had more fortunate consequences, also belongs to this period. Late in the summer of 1862, he had descended at the Mt. Clemens station and was waiting on the platform while the mixed train switched back and forth shunting a heavy boxcar out of a siding. The boxcar finally rolled toward the station, when Edison noticed that the little three-year-old son of the stationmaster was playing in the gravel, right on the main track, in the path of the car. In an instant he had thrown aside his bundle of papers, dashed toward the child, and snatched him up in time to avoid the car. The stationmaster, J. U. Mackenzie, was called out, and young Edison handed him his baby, whose life he had saved by his quick action — though, as he recalled it, there was ample time and little risk. Later the story was retold with many embroideries, but it was substantiated by the father.

Everyone present made much of the Edison boy. Mackenzie was filled with gratitude and expressed a desire to repay him in any manner within his power. He had noticed how Tom Edison hung over his telegraph table constantly. On the instant, the happy idea came to Mackenzie of offering to teach the boy to be an operator. Edison fairly leaped at the proposal. He had at that time, in the care of his mother, most of the “immense sum of money,” a hundred or a hundred and fifty dollars, that he had won through his business coup after the Battle of Shiloh. Mackenzie invited Edison to come and board with his family at Mt. Clemens for a couple of months, merely paying for the cost of his food, while taking his lessons in telegraphy every night and assisting the train dispatcher. He now gave up half of his newspaper route to another boy so that he could stop off at Mt. Clemens and study. He was only fifteen and a bit undersized. But in a few months he would be a real telegrapher.

At twelve to fifteen Tom Edison seems both boyish and old for his years. His mental growth proceeded at an uneven pace; indeed, in view of his deafness and poverty one would judge that he was under a severe handicap in the matter of continuing his education. If he had been one of your sensitive plants he would undoubtedly have been crushed out as so many unknown talents or geniuses are blighted in the budding.

Talent, or genius, however, shows itself in many different forms, for reasons that are, so far, incalculable. When Tom Edison feels things look desperate, he can become remarkably “cheeky,” as he phrases it — in other words, aggressive and competitive. Within him there is a passionate curiosity to learn certain things; he works alone at his elementary experiments for long hours and enjoys himself heartily. But on the other hand he knows a good deal about the world too, and can cope with it, supporting himself as a huckster, helping his family, and even cunningly leading his father by the nose — when he wants to stay up and play with his telegraph set instead of going to bed at a decent hour. Even in boyhood he is a sly one. There is in him both a highly imaginative and contemplative fellow, and a shrewdly calculating one, eager to make his way in the world. Meanwhile the vocation of telegraphy seems just the thing for him — he can hear and communicate with people; he can function.