Saladin, or Yusuf Ibn Najm al-Din Ayyub Salah al-Din to give the shortened version of his proper name, lived at a time when the Islamic world was going through profound changes. Since the later 11th century Turkish ruling elites had dominated most of the Islamic Middle East. In military terms Arabs and Persians were being pushed aside, though they continued to dominate the religious, cultural and commercial elites. Meanwhile Kurds had only limited and localized importance, which makes the rise of a man of Kurdish origins like Saladin all the more unusual.

During this period the cultural centre of the Islamic world also shifted westwards from Iran and central Iraq to northern Iraq, Syria and Egypt. Baghdad, capital of the Sunni Muslim ‘Abbasid Caliphate, retained its importance but was being rivalled by Mosul, Aleppo, Damascus and, after Saladin overthrew the Shia Muslim Fatimid Caliphate in Egypt, Cairo. Iran and Iraq had been the heartlands of Great Saljuq Turkish power but even here the Saljuq realm would fragment shortly after Saladin’s birth. In Baghdad the ‘Abbasid Caliphate, having long been a pawn in the power games of other dynasties, was also beginning to re-emerge as a significant power.

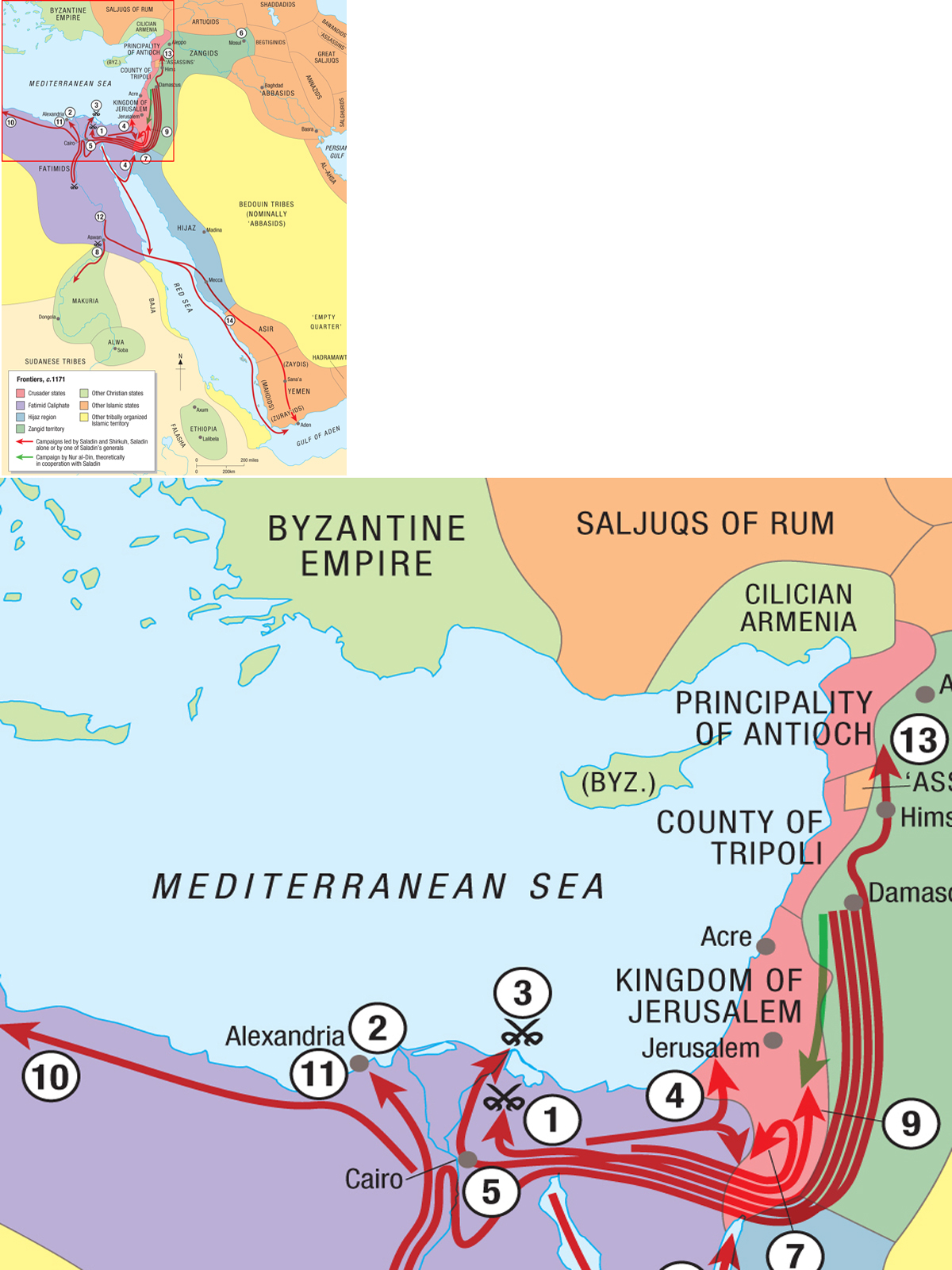

1 1164: Saladin accompanies Shirkuh with an army sent to the Fatimid Caliphate by Nur al-Din of Syria against King Amalric of Jerusalem’s second intervention; he defeats the Fatimids at Qawn al-Rish on 18 July, but is besieged in Bilbays from August to November and withdraws to Syria.

2 1167: Saladin and Shirkuh campaign against King Amalric of Jerusalem’s third intervention, defeating the Crusader–Fatimid alliance at al-Babayn on 18 March; Saladin leads the defence of Alexandria (May–June), then withdraws to Syria.

3 1169: Saladin and Shirkuh are invited to bring an army to Egypt to confront King Amalric’s fifth intervention; Saladin takes over as commander of Nur al-Din’s forces in Egypt after the death of Shirkuh and is appointed wazir of the Fatimid caliph (March); Saladin crushes a rebellion by Sudanese regiments of the Fatimid caliphal army (August) then defeats a Byzantine–Crusader siege of Dumyat (October–December).

4 1170: Saladin raids Darum and Gaza, and retakes Aylah from the Kingdom of Jerusalem (December).

5 1171: Saladin takes over as governor of Egypt on the death of the last Fatimid caliph, ruling in the name of Nur al-Din of Syria (September).

6 1171: Mosul recognizes the suzerainty of Nur al-Din.

7 1171: Aborted joint attack on Karak by Saladin and Nur al-Din (September–November).

8 1172: Nubians attack Aswan; retaliation by Saladin’s brother Turan Shah installs a garrison in Qasr Ibrim (summer to December).

9 1173: Saladin leads an army against Bedouin tribes in Oultrejordain to secure a route between Egypt and Syria, then raids Karak (summer).

10 1173: Saladin sends an army under Qaraqush on its first expedition into Libya.

11 1173: Sicilian–Norman fleet attacks Alexandria (July–August).

12 1173: Pro-Fatimid rising in Upper Egypt led by Kanz al-Dawla, the governor of Aswan, is crushed by Saladin’s brother al-’Adil (August–September).

13 1174: Death of Nur al-Din (15 May); Saladin takes control of Damascus, Hims and Hama (October–December).

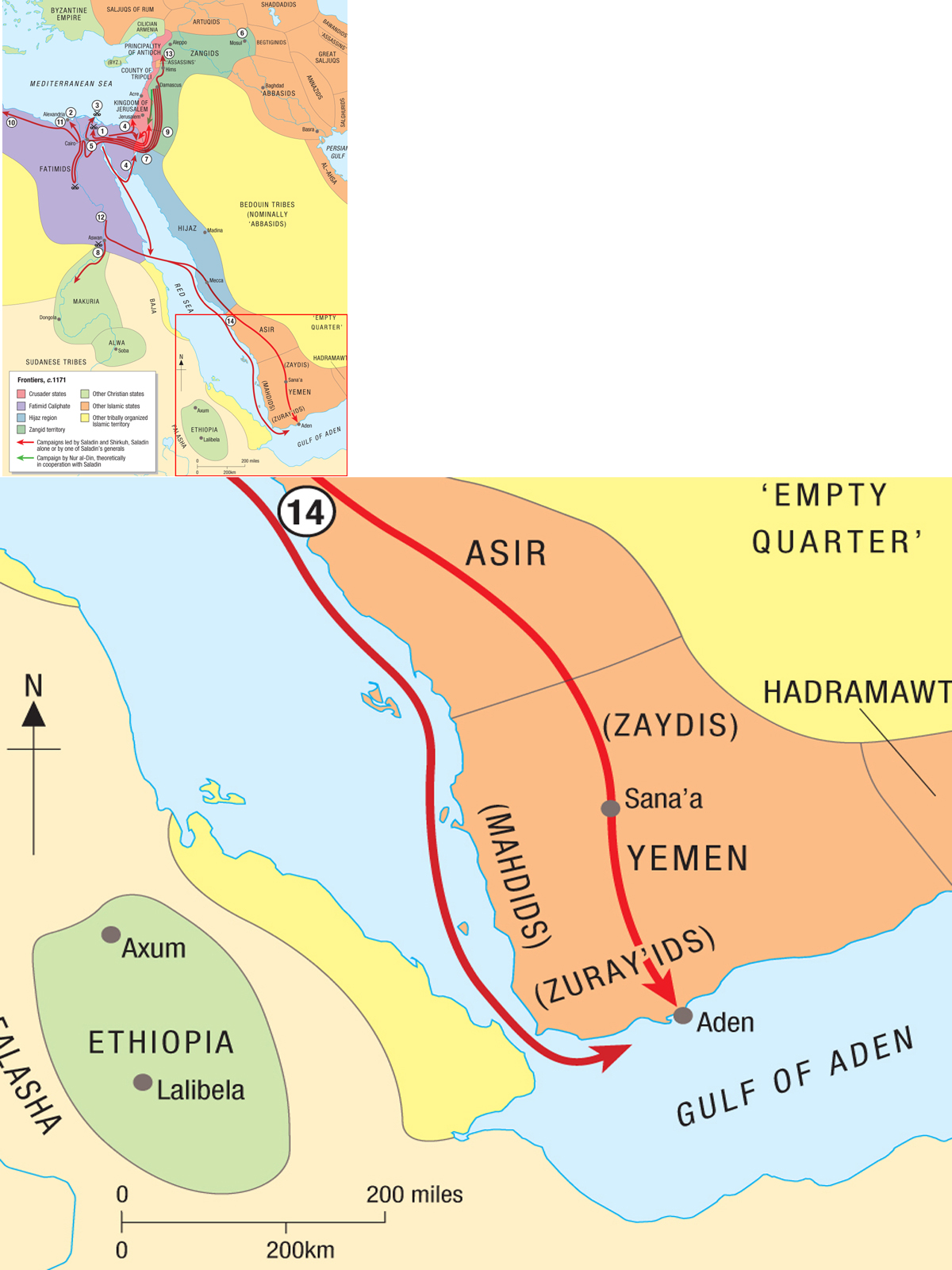

14 1174: Saladin sends Turan Shah with an army and supporting fleet to conquer Yemen (February–June).

During the Middle Ages Jazirat Ibn Umar (now Cizre in south-eastern Turkey) served as a major river port as well as a strategic crossing point over the Tigris. (Author’s photograph)

To the north and west, in the Jazira (Mesopotamia) region between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, and in most of Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Palestine and parts of southern Turkey, Great Saljuq authority had already been replaced by that of atabegs (‘princes’ father-figures’). Indeed the atabeg state founded by ‘Imad al-Din Zangi would itself be divided between his sons, of whom Nur al-Din inherited his father’s role as the leading Muslim champion against the invading Crusaders. He would also be Saladin’s patron.

The power of the Crusader states that had been established in the aftermath of the First Crusade (see Campaign 132: The First Crusade) was not yet broken, though the County of Edessa, the first Crusader state to be created, had been destroyed by ‘Imad al-Din Zangi. Nur al-Din then retook most Crusader territory in the Orontes Valley, reducing the once-powerful Principality of Antioch to little more than a narrow coastal strip along the Mediterranean. The Crusader County of Tripoli remained virtually unchanged while the most powerful Crusader state, the Kingdom of Jerusalem, remained a potent threat with ambitions to expand eastward while also striving to dominate Egypt where the decline of the Fatimid Caliphate was now clear to all.

Of course, rulers like Saladin and Nur al-Din had to keep in mind other Christian communities within their own realms. Many parts of Syria and Egypt still had local Christian majorities, while others had substantial Christian minorities; this was also true of several parts of the Jazira. Nevertheless, most such indigenous Christians were regarded as heretics by the Crusaders. Furthermore, the Islamic civilization in which Saladin was born and brought up had several Christian states and peoples as neighbours, other than those of the European Crusaders. Cilician Armenia had forged a close alliance with the Crusader states, while Georgia was enjoying a political, military and cultural golden age. In fact, conflict between an expansionist Georgia and the Muslim rulers of Akhlat meant that the latter rarely took much interest in the struggle against the Crusaders. The Byzantine Empire was now a reduced, through still formidable, power, having recovered much of the territory lost in the later 11th century.

Saladin’s primary concerns were, of course, affairs within the umma or community of Islam. Here tensions between the Sunni and the Shia strands of Islam were deteriorating rapidly. Today Shia form a majority only in most of Iran, plus southern and parts of central Iraq, though there are also significant Shia communities in Syria, Lebanon and Yemen. Before the mid-12th century, however, the size of Shia Muslim, Christian, Jewish and other communities meant that supposedly mainstream Sunni Muslims actually formed a minority in many parts of Egypt and Syria. It is therefore no exaggeration to state that the revival of Sunni ‘orthodoxy’ championed by leaders like Nur al-Din and Saladin was aimed at least as much against the Shia as it was against the invading Crusaders.

‘Jason the Hero’ in a copy of al-Sufi’s Book of Stars made within a few years of Saladin’s birth, probably in Egypt. (Topkapi Library, Ms. Ahmad III, 3493, f.30r, Istanbul)

By Saladin’s lifetime the mace came in a variety of forms, ranging from the animal-headed gurz (A) to the flanged dabbus (B) and elongated latt (C). (A – Furusiyya Art Foundation, London; B – private collection, Israel; C – Museum of Islamic Art, Cairo)

To understand the strengths and the weaknesses of Saladin’s position it is necessary to look at the theoretical basis of his authority. The medieval Middle East was an arena where religious law rather than military power ultimately decided whether a dynasty could maintain itself. Here, perhaps even more than in medieval Europe, an ambitious ruler needed the acquiescence of his people and the support of religious or legal as well as military elites if he was to achieve anything.

The men shown on this 12th-century Kashan-ware moulded jar from Iran are dancing in the same manner that can be seen across most of the Islamic Middle East to this day. (Private collection)

During the late 11th to early 13th centuries Sunni Muslim scholars reinterpreted the role of the Sunni caliph as imam or spiritual leader of the Muslim community. Most day-to-day power lay in the hands of sultans, but rulership was defined as a partnership between a sultan and the caliph. Nevertheless, there could be no legal separation of ‘church and state’ in societies firmly based upon Islamic law. What a scholar like al-Ghazali outlined was a system where the sultan carried on the business of government, but only if his authority was formally recognized by the ‘Abbasid caliph. Unfortunately, the current caliphs of Baghdad, while still being the spiritual leaders of Sunni Islam, were also becoming militarily significant rulers. From Saladin’s point of view, the scope for ‘Abbasid interference remained a problem, especially as he was himself widely regarded as an usurper who had turned against the sons of his master, Nur al-Din. Hence the importance of Saladin’s fight against the Crusaders as a way of legitimizing himself as the strongest ruler in the Middle East.