Saladin’s life and achievements were viewed very differently in the Islamic and Christian worlds. Even so, Western European Latin Catholic opinions of the great Islamic hero changed quite quickly. The anonymous Chronicle of the Third Crusade was written immediately after the event, by a participant who reflected on the widespread horror at the fall of Jerusalem to Muslim ‘infidels’. It blamed Saladin’s success on the failings of the Crusader states: ‘The Lord saw that the land of His Nativity, the place of His Passion, had fallen into the filthy abyss. Therefore He spurned His Inheritance, permitting the rod of His Fury, Saladin, to rage and exterminate the obstinate people.’

The epic quality of the struggle that followed was recognized on all sides and although the sources are not as apocalyptic as those dealing with the First Crusade, they were more emotionally charged than most that recounted later Crusades. In this sense the Arabic texts are particularly interesting as they reflected a change from near euphoria after the battle of Hattin to growing despair as Muslim forces fell back before the Third Crusade. Eventually Saladin fought King Richard to a standstill, but this could not disguise the fact that he was now on the defensive. During the prolonged siege of Acre Saladin almost used up his military, naval and economic resources – perhaps also exhausting himself.

By the start of the 20th century the madrasah or college containing Saladin’s tomb in Damascus had fallen into decay. When Kaiser Wilhelm II visited the city in 1908 he had the tomb restored at German expense. (Author’s photograph)

Not surprisingly, Western accounts highlighted any evidence that Saladin admired the leaders of the Third Crusade. When Bishop Hubert of Salisbury made his pilgrimage to Jerusalem, the Muslim ruler told him: ‘It is well known to us that the king [Richard I of England] has the greatest prowess and boldness, but he frequently hurls himself into danger imprudently, I do not say foolishly… Wherever and in whatever kinds of countries I may be the distinguished prince, I would much prefer to be enriched with an abundance of wisdom and moderation, rather than with boldness and lack of self control.’13 In the eyes of westerners Saladin was, in fact, already seen as a wise, but crafty and not particularly brave, leader.

Saladin’s tomb lies beneath the small, fluted and red-painted dome immediately in front of the northern minaret of the Umayyad Great Mosque in this photograph. (Author’s photograph)

Muslim opinions of Saladin were also varied, with chroniclers being divided into pro-Ayyubid and pro-Zangid camps. Most tried to hide their political loyalties but these occasionally burst through, as when ‘Imad al-Din al-Isfahani said of the Islamic year 583 AH (12 March 1187 to 2 March 1188): ‘It is the second Hijra of Islam, but this time to Jerusalem [the first having been the Prophet Muhammad’s move from Mecca to Madina]… It can justly be regarded as the beginning of a new era, since it marks a turning point in the course of Islam.’

The chronicler Ibn al-’Athir actually fought for Saladin against the Crusaders and was quite open about Muslim mistakes. These included Saladin’s failure to attack Guy de Lusignan’s force before it reached Acre in August 1189: ‘Were it not for the fact that the army followed the opinion of Salah al-Din in their manner of arrangement and fighting before they reached Acre, they would have achieved their aim and blocked [the enemy] from it.’

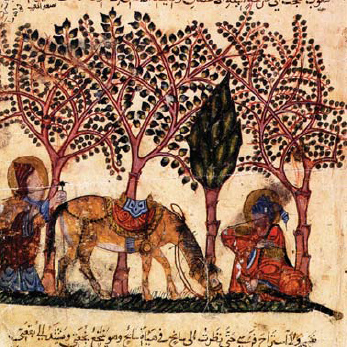

The faces in this early 13th-century Iraqi or Syrian copy of the maqamat by al-Hariri have been smudged out. Both the men and the horse have also been decapitated by black lines drawn long after the manuscript was made. Nevertheless the costumes and the horse’s saddle are shown in interesting detail. (Institute of Oriental Studies, C-23, f.174, St Petersburg, via V. A. Livskity)

Writing about Saladin’s enthusiasm for war against the Crusaders, Baha al-Din was more supportive: ‘In his love for the Jihad on the path of God he shunned his womenfolk, his children, his homeland, his home and all his pleasures, and for this world he was content to dwell in the shade of his tent with the winds blowing through it left and right.’ Baha al-Din was equally impressed by Saladin as a commander: ‘I have never at all seen him consider the enemy too numerous nor exaggerate their strength. However, he was sometimes deep in thought and forward planning, dealing with all departments and arranging what was required for each without any onset of bad temper or anger.’

Nevertheless, resentment occasionally surfaced in later chronicles and is seen in the words of the leader of an Arab revolt against the Mamluk takeover of Egypt in 1250: ‘We are the lords of the land. We are more worthy to rule than the Mamluks. It was enough to serve the Ayyubids [the dynasty established by Saladin], who were rebels and took the land by force, and they [the Mamluks] are only the slaves of the rebels.’14

The depth of Western European ignorance and misunderstanding of the Islamic world at the time of the Third Crusade is apparent in the anonymous Chronicle of the Third Crusade, which claimed that Saladin

was from the nation of Mirmunaenus [a corruption of Amir al-Mu’minin or ‘Leader of the Believers’]. His parents were not descended from the nobility, but neither were they common people of obscure birth… Saladin collected illgotten gains for himself from a levy on the girls of Damascus. They were not allowed to practice as prostitutes unless they had obtained, at a price, a licence from him for carrying on the profession of lust. However, whatever he gained by pimping like this he paid back generously by funding plays. So through lavish giving to all their desires he won the mercenary favour of the common people.

Saladin’s caution was similarly portrayed by Ambroise as cunning or treacherous. Admiration for the virtues of a few Saracen heroes only came to the fore in late 12th- and 13th-century texts, with Saladin being central to this altered image. Saladin was also given an unexpected position in the medieval Italian poet Dante’s Divine Comedy. Not being a baptized Christian, he could not be placed in Paradise, but by 1300 Saladin’s reputation was high enough for him to reside in Limbo rather than Hell: ‘And there across that bright enamelled green, these ancient heroes were displayed to me… All these I saw, and there alone, apart, the sultan Saladin.’15

During the 19th century Saladin came to be seen by many in Europe as a heroic figure – the archetypal noble Saracen foe. As a result biographies such as that by Stanley Lane-Poole tended to be uncritical. Saladin’s position in the pantheon of Muslim heroes has also inhibited critical scholarship in the modern Arab world, although several recent Arab historians have focused more upon Saladin’s predecessors and have thus downgraded Saladin’s own achievements. Similarly, the Arab world’s adoption of Saladin as a role model in the struggle against Israel has encouraged several pro-Zionist historians to seek, consciously or otherwise, to debunk him.

In contrast, it is interesting to find that Western rather than Muslim historians have emphasized the legitimacy of Ayyubid rule compared to that of their supposedly ‘slave’ Mamluk successors. In most of the medieval Islamic world, with the notable exception of the caliphate itself, legitimacy was a prize to be won like any other within the Islamic political system. Westerners, both medieval and modern, have also tended to see the fast-changing and complex political circumstances of the medieval Middle East as evidence of disorder, corruption and intrigue. The truth is that this part of the medieval world was politically more fluid, more meritocratic and to some extent more democratic than medieval Western Europe.

One disadvantage of this fluidity was that, despite his remarkable leadership and political skills, Saladin never succeeded in shaping Egypt and Syria into a single ideological, military or economic unit. This weakness became all too apparent after his death, when the Ayyubid realm or realms were little more than a collection of competing family fiefdoms.

It took an essentially unsympathetic, though hugely knowledgeable, modern biographer like Andrew Ehrenkreutz to highlight the shortcomings of Saladin’s leadership:

Despite his popular image following the great victory of Hattin and the glorious recovery of Jerusalem, Saladin’s position as leader of the Muslim forces fighting the Crusaders was not too comfortable. As early as 1186, incidents with Nasir al-Din ibn Shirkuh and Taqi al-Din Umar had indicated that Saladin could not even trust his own relatives. Events at Tyre in 1187 had revealed that the rank and file was not overwhelmingly inspired by the jihad ideal which Saladin publicly embraced, and this self-asserted mandate itself had been repudiated in no uncertain terms by the caliph of Baghdad.16

A more sympathetic historian like P. M. Holt could still study the numerous recorded letters from Saladin’s court and conclude that: ‘The Saladin who emerges from these pages is no longer the confident and dedicated champion of Islam, even if he is not the anti-hero, disastrous to Egypt, depicted by Ehrenkreutz. The precarious nature of his position appears constantly. The jihad was a means of legitimising his authority.’

Lyons and Jackson similarly noted Saladin‘s precarious military position:

When Saladin retook Jerusalem in 1187, he had a new pulpit of wood and ivory, which Nur al-Din had prepared for this day, placed in the al-Aqsa Mosque. Sadly, the passions that can still be aroused by the Crusades resulted in an Australian fanatic setting fire to the mosque in 1960 in the belief that this would hasten the Second Coming of Jesus, and destroying Nur al-Din’s pulpit in the process. (Author’s photograph)

A factor which has to be taken into account was the loose structure of his army. His allies had no reason to give him whole-hearted support. For his own emirs and professional soldiers he and his family were merely successful members of their own class; his dynasty was bolstered by no divine right of kings and the religious sanction it had claimed had been denied it by Baghdad. During the period of its expansion it had been profitable to join his side, but profit and numbers were inextricably linked. If his military accounts began to show a loss, his numbers could be expected to diminish and his dynasty in its turn could be theatened by other muslim expansionists.17

The Western European knightly class soon came to see Saladin as a worthy, though doomed, opponent of the Crusaders and a mythical combat between the Muslim hero and the English King Richard the Lionheart became a favourite theme in both literature and art. (© The Trustees of the British Museum, all rights reserved, inv. no. 1885, 11–13, London)

Viewed dispassionately as the ruler of a frontier region facing powerful Crusader states, Saladin emerges as one in a series of leaders who used this situation to build a state through winning support as a defender of the region against its enemies. It was a process seen throughout history in many parts of the world. Nevertheless there is no denying that Saladin was more successful than most of his contemporaries in overcoming the factionalism that had for centuries undermined traditional Middle Eastern Muslim military systems, most obviously that of his Fatimid predecessors in Egypt. Therein, perhaps, lay the real secret of his success.

13 Anon. (tr. Nicholson, H. J.), Chronicle of the Third Crusade (Aldershot, 2001) p. 378.

14 Holt, P. M., ‘Saladin and his admirers: A biographical reassessment’ in Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 46 (1983) p. 130.

15 Dante (tr. Griffiths, E. & Reynolds, M.), Dante in English (London, 2005) Canto 4, Limbo, ll. pp. 118–29.

16 Ehrenkreutz, A. S., Saladin (Albany, 1972) pp. 210–11

17 Lyons, M. C., & Jackson, D. E. P., Saladin: The Politics of the Holy War (Cambridge, 1982) p. 286.