Your great-grandparents lived by the saying, "Waste not, want not," which means that if we don't squander what we have, we won't lack for it later. That's a far cry from today's throwaway mentality, isn't it? Whether it's clothes, a cellphone, or a DVD player, many people find it easier to replace something that's old, worn, or broken than to fix it. The amount of trash people in developed countries produce is staggering, as you'll see in this chapter. And it piles up fast—just how fast might surprise you. What happens to all that junk? And how can we scale back the literal mountains of trash that go into landfills?

Everyone has to do their part. You're no doubt familiar with the phrase, "reduce, reuse, recycle," which is an updated, eco-conscious version of the "waste not, want not" philosophy. By now, most people have heard these three Rs so much that they seem obvious—of course we should be doing all those things to ease the toll we take on the planet. But it's worth pondering whether you actually follow all three Rs as much as you could.

This chapter shows why wasteful living is a bad idea and teaches you tips to help minimize it. By taking a close look at each of the three Rs—how you currently implement them and how you might fine-tune your current practices—you'll minimize waste, conserve precious resources, and save energy that would otherwise be used to create and transport new goods. And you'll feel smug knowing you're doing your part for planet earth.

Every week, you haul your trash to the curb, drop it down a chute, throw it into a dumpster, and then a truck comes by and takes it away. Have you ever thought about what happens after that?

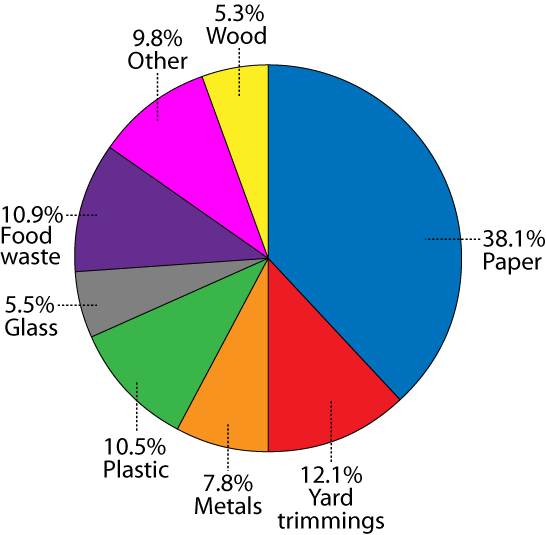

Most people haven't. Yet the average American produces about 4.5 pounds of garbage each day—that adds up to over 1,600 pounds a year! Multiply that by 300 million Americans, and you may wonder why we're not wading through a layer of junk up to our knees. Just imagine—if you had no way to get rid of your trash, how long would it take to fill up your house or apartment?

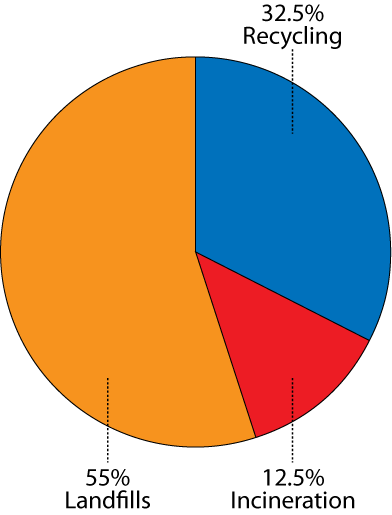

After the garbage truck drives off, your trash is likely transferred to a barge or to other trucks, which might drive hundreds of miles before they dump it. There are two main places where trash ends up: buried in a landfill or burned in an incinerator.

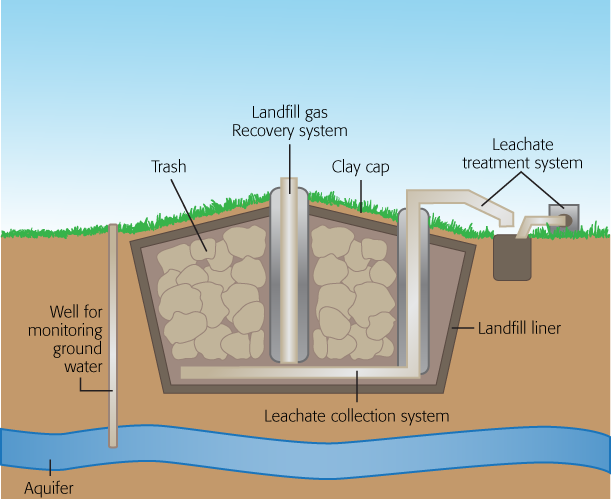

After your trash gets picked up, it probably gets taken to a landfill, which is where more than half of America's trash ends up. Today's sanitary landfills (what a name, huh?) aren't the hole-in-the-ground dumps where your grandparents tossed their trash. (The federal government banned open dumps in 1976.) Sanitary landfills isolate trash from the environment until the trash has degraded and doesn't pose health or environmental threats. That's the theory, anyway.

A containment landfill, a type of sanitary landfill, is a big pit that holds garbage from towns and cities. The pit has a waterproof liner, made of clay or plastic, along its sides and bottom to prevent contaminated liquids (known as leachate) from getting out of the trash-holding area and into the environment. A collection system drains the liquid from the pit and pumps it to a treatment system, where it's cleaned. Around the landfill, wells let workers collect groundwater so they can test it and make sure it's not polluted.

Note

In containment landfills, even biodegradable stuff breaks down very slowly. Archeologists excavating old dumps have found 30-year-old grass clippings and still-legible newspapers. The trash in landfills stays with us for a long, long time.

As the garbage in the landfill degrades, it releases mostly methane and carbon dioxide, along with a few other gases. Usually, this gas gets burned off—if you've ever driven past a landfill and seen a flame at the top of a tall chimney, that's what it's for.

Note

Methane is the main component of natural gas, and landfills are one of the top sources of man-made methane. Some landfills burn the methane they create to generate electricity.

Each day, workers bulldoze the trash and cover it with a layer of dirt or ash to help with the smell and to keep animals from using the dump as an all-you-can-eat buffet. Large landfills, which can cover hundreds of acres, have several pits, and only some of them get used at any given time, to minimize wind and rain exposure. When a pit is full, it gets covered with a clay cap to seal it, and then a layer of dirt and grass seed is put on top of that. The area then can get turned into a golf course, parking lot, or park. (It can take a long time for the ground to settle, so building on top of an old landfill is rarely an option.) Even after a dump has closed, scientists monitor the area's groundwater—for 30 years or more.

Bioreactor landfills, another kind of sanitary landfill, are specially designed to help biodegradable trash decompose quickly. Air and water get circulated through the pit, speeding up the breakdown process. (You may have heard the word "bioreactor" before in different contexts. It's a broad term that can refer to any kind of setup that helps some biological or chemical process happen, from decomposition to making cells grow in a lab.) This kind of landfill produces more methane (which gets used to create electricity) and degrades organic garbage faster than the containment kind.

Modern landfills are much better than old-style dumps, which polluted groundwater and contaminated soil. But even with today's technologies, bulldozing trash into pits has its downside. Many areas are running out of space—often because locals don't want waste dumped in their area. (Would you want a garbage heap in your backyard?) Landfills also cause the following problems:

Increased traffic. A parade of heavy trucks haul load after load of trash to the site. This increases traffic on local roads, which often weren't designed for such trucks.

Lower property values. Although landfills provide jobs, they lower the value of homes and other real estate around them.

Rats, seagulls, and other scavengers. Landfills attract critters looking for meals—and if it isn't well managed, these scroungers can overrun the area around it, too.

Greenhouse gas emissions. As mentioned earlier, decomposing garbage produces methane, carbon dioxide, and other gases. Methane is a serious greenhouse gas—it stays in the atmosphere for 9–15 years and traps 20 times more heat than carbon dioxide. Burning the methane isn't a great option because that creates carbon dioxide and water, and CO2 is bad for the atmosphere, too.

Leaky liners. Landfills' liners sometimes leak and the leachate contaminates groundwater.

Hazardous materials. Dumps that collect municipal solid waste (MSW)—that's the stuff regular people throw away—have different regulations than hazardous-waste landfills, which deal with pesticides, certain drugs, industrial wastes, and so on. Yet more scary stuff could be going into the local dump than you realize. Many MSW landfills accept soil contaminated by gas spills and certain kinds of hazardous waste from businesses. And some of the toxic household chemicals you learned about in Chapter 1 end up in landfills, too, mostly because people don't know how to dispose of them properly. All these nasty chemicals end up in the landfill's leachate.

Health issues. Lots of problems have been reported among people living near MSW and hazardous-waste landfills alike, including low birth weights, birth defects, respiratory problems, dermatitis, neurological problems, and cancer.

Most cities areas have laws against burning trash in your backyard. That's because, aside from the risk of setting your house on fire, burning household trash sends a lot of pollutants—including cancer-causing dioxins—into the air. According to the EPA, backyard trash fires are the number one source of dioxin emissions in the U.S. (Dioxins, one of the most toxic substances on earth, build up in your body over time and have been linked to cancer, reproductive problems, thyroid disorders, central nervous system disorders, and immune system damage.) A single barrel of trash burned in the open may create as much air pollution as tons of garbage burned in a municipal waste incinerator serving tens of thousands of homes.

Note

In many rural areas, it's legal to burn trash on farms. The dioxins that get released can settle on plants or wash into water, harming the critters that eat the plants or live in the water. And the chemicals move up the food chain: More than 95% of Americans' dioxin exposure comes through food—fish, red meat, poultry, dairy products, and eggs.

Municipal incinerators are a smarter way to burn trash. They deal with about 12% of the waste produced in the U.S. each year. (In other countries, like Japan and parts of Europe, the percentage of incinerated garbage is higher.) These facilities start with tons of trash, burn them at really hot temperatures, and end up with heat, gases, airborne particulates, and ash. They're safer than open burning and reduce the volume of solid waste by as much as 95%. The high temperatures destroy most germs, toxic chemicals, and other nasties, but the ash that's left over sometimes needs to be tested to make sure it's free of contaminants, depending on what was burned. Some of the ash gets used in paving materials and as daily cover for landfills.

Note

Waste-to-energy (WTE) incinerators burn waste to generate power in the form of heat, steam, or electricity. There are currently 89 WTE plants in the U.S., generating enough juice each year to provide power to 2.3 million homes.

But there are problems with cremating trash. A big one is emissions: Incinerators spew out lots of carbon dioxide and some other seriously nasty gases like nitrogen oxide, sulfur dioxide, mercury, dioxins, and furans, although the EPA sets rules to minimize these. Even so, dioxins and furans are highly toxic—there's no "safe" exposure level.

Also, the teeny-tiny particles produced by burning that are too small be trapped can lodge in people's lungs, leading to respiratory problems and lung disease. And much of the ash created by incinerators isn't recycled and used for other purposes; it's dumped in single-use landfills called monofills. An ash monofill contains nothing but incinerator ash, and some environmentalists worry about toxic materials and heavy metals (such as lead, mercury, and arsenic) building up in these sites over time.