Venezuela still has a living calendar of customs and traditions that have a real meaning for the people who participate in them, and give shape to their year. For the Devil Dancers who don masks and attack the Church during the Feast of Corpus Christi there is a spiritual danger to their acts, and they wear amulets and receive blessings from the priest to keep them safe. Equally, for the drummers of Barlovento or Chuao who play for St. John the Baptist on his day, the music and dancing are a direct connection with their roots in Africa.

Días feriados (public holidays) and fiestas (feast days or festivals) are taken very seriously in Venezuela. Sometimes, especially from the start of the year through to Semana Santa (HolyWeek/Easter) in March or April, it can seem as if the country is on one long holiday—after Christmas and New Year, things don’t get back to normal in many businesses until January 15, and before you know it Carnival has arrived.

It is also typical for businesses to shut down early before public holidays, as many people travel long distances to visit relatives, or take the family to the beach or the mountains for a barbecue and a swim.

Not surprisingly, traffic is generally gridlocked before and after Christmas, Carnival, and Holy Week, and bus terminals and airports get quite frantic as the crowds compete for limited seats.

When a public holiday falls on a Thursday or a Tuesday, many people will take an extra day off, known as a puente (bridge), so they can have a four-day weekend.

In December Venezuelan children are busy writing letters to El Niño Jesús (Baby Jesus), listing the presents they are hoping to receive. Otherwise the days before Christmas are a time for dancing to gaitas music from Zulia, reunions with friends, and parties at work. In many offices, workers set up a “Secret Santa”—you take the name of one colleague out of a hat and buy them a present to leave on their desk or to hand out at the office dinner or party. Many houses, schools, banks, and stores will provide a table or a corner for a pesebre (nativity scene), which can be quite elaborate. After workers collect their Christmas bonuses a great exodus takes place as people travel from the cities to their hometowns. Business activity begins to wrap up from December 15 to 18 until the schools open again after January 6.

On Christmas Eve, families assemble for dinner at about 10:00 p.m. Traditional for this meal are hallacas (corn-dough parcels with a filling, wrapped in a plantain leaf), ensalada de gallina (shredded chicken, diced potatoes, peas, and mayonnaise), pernil (roast shoulder of ham), and pan de jamon (a long, thin bread with ham and raisins inside). Sparkling wine, whiskey, or beer may be drunk, but the traditional festive tipple is ponche crema, a creamy blend of condensed milk with rum or brandy served in small glasses, like eggnog.

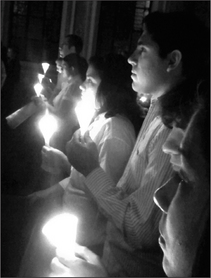

Midnight is greeted with noisy fireworks and general merrymaking as adults exchange gifts around the Christmas tree and children receive their presents from El Niño Jesús. Many people will attend the Misa de Gallo (Midnight Mass) in the local church, where aguinaldos (hymns) are sung.

Christmas Day is not a big deal for most families. Stores are closed, and people either stay at home with the family or visit friends and relatives.

The most important dish at Christmas is without doubt the hallaca (pronounced “eye-ya-ka”), a cornmeal-dough pocket stuffed with tasty ingredients, wrapped in a plantain leaf, and boiled. Similar to the tamales and humitas served in other parts of Latin America, the hallaca is eaten only at Christmas, and has pride of place on the Christmas dinner plate.

The exact origin of the hallaca is not known, but it is believed to come from the custom of plantation owners giving their slaves the leftovers from their Christmas banquets. The slaves would add these scraps to the boiled cornmeal dough (known as bollos) that made up their daily diet. That is why hallacas are stuffed with such an odd range of things, from chicken, beef, and pork stew to olives, raisins, capers, and even boiled eggs, depending on the family recipe.

Making hallacas is an elaborate process with many stages, and in Venezuela usually involves the whole family, who will spend a weekend making enough hallacas to last a month, each one wrapped in a leaf and tied with string, like a little present.

New Year traditions in Venezuela involve various ways of saying good-bye to the old year and welcoming the new one in a way that will bring good luck, good health, love, and prosperity. Sold by street vendors and smart lingerie stores alike, yellow underwear (the color of gold) is worn by both men and women to bring luck and money in the year to come. Red pants are believed to improve your chances at finding love and romance. Another popular custom is to wear new clothes—known as estrenos—to start the year well dressed.

New Year’s Eve parties follow the same pattern as Christmas Eve, with a late meal of traditional Christmas food, and dancing to festive music such as gaitas, salsa, and reggaeton. Typical New Year tunes are “Viejo Año” by Maracaibo 15, Nestor Zavarce’s tearjerker “Faltan Cinco Pa’ Las Doce” (“Five Minutes to Twelve”), and “Año Nuevo, Vida Nueva” (“New Year, New Life”) by Billo’s Caracas Boys.

Just before midnight everybody takes twelve grapes and a glass of sparkling wine. The idea is to gobble down a grape for each of the twelve chimes, with each grape representing a good month in the year to come. The last chime of midnight ends with the deafening sound of los cañonazos—the fireworks that mark the start of the New Year, and hugs and kisses all round.

In the Andean states of Mérida and Tachira they say good-bye to the old year by parading papier-maché figures through the streets and burning them at midnight, to the sound of gaita music and the deafening explosions of thousands of triquitraquis (firecrackers).

Venezuela has nothing to rival the world-famous carnival celebrations in Brazil, but many towns have street parties and parades. In Caracas there are small parades for children in fancy dress, but the biggest celebrations are held in Carúpano, where floats with sound systems and followers in carnival costumes do circuits of the town.

The most distinct celebration is in El Callao, Bolívar State, where West Indian and Antillean immigrants arriving in an 1880s gold rush brought calypso, which is still sung in English. Popular carnival characters in El Callao include women in African-style head scarves and dresses reminiscent of nineteenth-century Guadeloupe called Las Madamas; masked diablos (devils) with tridents and tails who keep the crowds in check; and the mediopintos—men and women with black paint who threaten to splash it over you if you don’t pay them.

In Mérida, Carnival coincides with the ten-day Feria del Sol, which features concerts, beauty pageants, and bullfights.

A movable feast in the Catholic Church celebrating the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus Christ, Semana Santa falls in March/April. It starts with Domingo de Ramos (Palm Sunday) and concludes with Domingo de Resurrección (Easter Sunday).

In Caracas the festivities begin with the blessing of palm leaves brought down from the Ávila Mountain by the Palmeros de Chacao. This tradition dates back to 1770, when the population of Caracas was decimated by a deadly outbreak of yellow fever. A local priest, José Antonio García Mohedano, made a promise to God that he would send men to cut palms on the Ávila every year if the fever stopped. Ever since then it has been a tradition among local families to pledge to cut palms for five, ten, or twenty years.

Colorful processions of people dressed in long purple robes take place in many cities and towns across the country on the evening of Holy Wednesday, when churches parade statues of Christ carrying the cross. On Viernes Santo (Good Friday) there are passion plays around the Stations of the Cross, with devotees dressing as Roman soldiers, the Virgin Mary, and Christ. A very realistic crucifixion scene is reenacted in Tostós in Trujillo State and in many villages around Mérida. Easter celebrations end on Sunday with the Quema de Judas (burning of Judas), in which papier-maché effigies of unpopular local figures or politicians are dressed in old clothes and publicly burned.

Spectacular festivals of masked diablos danzantes (devil dancers) take place in fourteen Venezuelan towns and villages in a centuries-old tradition brought from Spain and adapted to express the defiance of the African slaves, who were barred from entering church during Sunday mass. From sunrise the devils parade through town, causing mischief, mayhem, and general devilment until about midday, when they make a mock attack on the church. They are repelled by the priest, who holds aloft the consecrated hosts of the Eucharist. Three times the devils attack, and three times they are repelled. Finally, with good having triumphed over evil, the devils remove their masks and the street parties begin in earnest.

The most celebrated devil dancers are in San Francisco de Yare, which is near Caracas in the Valles del Tuy. Dressed from head to foot in red, the Yare devils carry maracas and wear multicolored horned masks made from papier-maché. In the coastal cacao plantation of Chuao, famous for its high-quality cocoa beans, isolation has helped to preserve many traditional elements of devil dancing, including costumes made of colored rags.

The feast of St. John the Baptist is celebrated in dramatic style with three days of Afro-Venezuelan tambores (drums) and call-and-response singing accompanied by vibrant dancing in which men and women circle closely around each other in fast, hip-swiveling movements that grow more suggestive as the night wears on.

Statues of the saint as a baby or child are dressed in red or blue and bathed in rum, before being paraded by flag-waving crowds through the towns of Curiepe and Birongo, and the coastal villages of Cuyagua, Choroní, Chuao, and Chuspa.

In some coastal towns the local fishermen take their local San Juan statue out to sea to meet those from other towns, then head back to land for an extended party.

Many popular beliefs and superstitions in Venezuela are linked to Catholic beliefs, especially the idea that you can make a pact with a saint or holy figure for help with an earthly problem that needs divine intervention. The person making the request must promise to do something in return and carry it out, which is known as pagando promesa. This is the driving force behind the diablos danzantes, who do not dance each year simply to keep an old tradition alive but instead make a solemn promise in front of the church to dance for a number of years.

For example, San Antonio, it is believed, can help you to find love if his statue is suspended upside down; or if you regularly light a candle and say a prayer in front of the image of San Onofre, it is said that he will help you to get a job or pass an exam.

The most popular of these folk saints is Dr. José Gregorio Hernández, a Venezuelan doctor who was killed in a car crash in 1919 and has been declared “venerable” by the Catholic Church. Although he is not officially a Catholic saint, there is great devotion to the good doctor. His tomb in the church of La Candelaria, Caracas, and his birthplace in Isnotú, Trujillo State, are popular places of pilgrimage, especially by the sick and infirm seeking a miracle cure. Known as “the doctor of the poor,” he is depicted wearing a black suit and hat with a Charlie Chaplin moustache, or in a doctor’s white coat.

An indication of the importance of magic in the lives of many Venezuelans is the number of stores known as perfumerías in most towns and villages. Offering tobacco readings and spiritual healing, they sell a dizzying array of soaps for washing away bad luck and love potions to make you irresistible, alongside shelves of saints, Buddhas, and strange paraphernalia for practicing brujería (witchcraft).

A uniquely Venezuelan blend of folk Catholicism and African and indigenous ritual, the mysterious and magical cult of María Lionza began in the mountains of Sorte in Yaracuy State, but became a countrywide phenomenon with the move to the big cities in the 1940s and ’50s. The closest parallels in Latin America are with Cuban santeria or Haitian voodoo.

Pilgrims come most weekends to carry out rituals in the forests of Sorte, with mediums in a trancelike state channeling the spirits of religious, mythical, and historical figures, such as Dr. José Gregorio Hernández, Simón Bolívar, and even a group of Vikings. At the top of this pantheon is a group known as the Tres Potencias (Three Powers): María Lionza, depicted as a queen with a crown; the black independence fighter Negro Felipe, and the Indian chief Guaicaipuro.

The Myth of María Lionza

María Lionza, or Yara, was an indigenous princess, the daughter of Yaracuy, chief of the Nivar tribe. Before her birth the shaman had pronounced that, if a girl with strange, watery-green eyes were born, she would have to be sacrificed and offered to the Great Anaconda, or she would bring death and destruction to the tribe. The chief, unable to sacrifice his daughter, hid her in a mountain cave with twenty-two warriors to guard her.

One day, while the guards were asleep, Yara left the cave and walked to a lagoon where she saw her reflection for the first time. Captivated by her own image, she was unable to move, but her presence awakened the Great Anaconda, who instantly fell in love with her. When she resisted its advances the anaconda swallowed the girl, but immediately began to swell up, forcing water out of the lagoon, flooding the village, and drowning the whole tribe. Finally, the anaconda burst and María Lionza was set free, becoming the protector of lakes, rivers, and all living things.

Rituals are carried out to the sounds of Afro-Venezuelan drums and crowds who chant “Fuerza, fuerza” (strength, strength) to encourage the entranced mediums. On days special to the cult, such as October 12, the noise can be overwhelming.

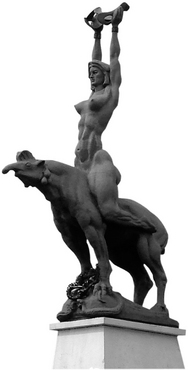

Nobody knows the true origin of the cult, or of María Lionza herself, who is sometimes called Yara, or La Reina (the Queen). Some images and statues show her as a European woman with a golden crown, others as an Indian princess living wild in nature. The famous statue in Caracas from the 1950s depicts her as a naked woman sitting astride a tapir, holding a human pelvis in her raised arms.

Venezuela has a rich tradition of folk music that combines indigenous, European, and African elements.

Joropo, or música llanera, is a musical style from Los Llanos and the most popular folk music in Venezuela. It is played wherever beef is being barbecued, and competes with salsa and merengue on many small buses. It is traditionally sung in a rough, nasal style by cowboy types in Stetsons and pointed boots, with music provided by a thirty-two-string harp, a cuatro (a small, four-stringed guitar), and maracas. Joropo evolved from the zarzuelas and cante jondo brought to Venezuela by the Spanish, and the jaunty pace of the music is said to evoke the galloping hoofs of a wild horse. Joropo is also a dance, a sort of waltz involving jerky, cucaracha-stomping steps by the man, known as zapateo, and dizzy twirls by his female partner.

Simón Díaz and Reynaldo Armas are perhaps Venezuela’s best-loved llanero singers, although legendary performers like Juan Vicente Torrealba, Ignacio “El Indio” Figueredo, and El Carrao de Palmarito are still played regularly on the radio. Talented young harpists include Leonard Jacome, who has experimented with joropo-jazz fusion, and Carlos Orozco, nicknamed “Metralleta” (machine gun) for his dazzling finger play. Every year festivals are held in Venezuela and Colombia, with prizes for the best singers, harpists, and dancers, and tests of lyrical skill called contrapunteo, when contestants try to outdo each other by inventing rhymes on the spot in a head-to-head battle.

If joropo is the music of the plains, then Afro-Venezuelan music called tambores (drums) is the sound of the beach. Harking backs to slave days, tambores is still played in the old plantation towns along the central coast, such as Choroni, Chuao, Puerto Maya, and the beach towns of Barlovento. Played fast and loud on long cumaco drums made from hollowed-out avocado tree trunks, tambores preserves West African polyrhythms, with one drummer playing a deer or cowhide skin on the front of the drum and two or more playing on the trunk with hard sticks called palillos. This is what gives the music the distinctive “taca-ta-taca-ta” sound that drives the dancing, which takes place in a circle formed by the cantor (singer) and the chorus.

One man and one woman dance together at any one time, the man trying to get as close as possible as he circles around her, shaking his hips, while she fends off his advances by spinning away from him. Other dancers can cut in at any time, and the dancing continues until the drummers give up or the rum runs out. During Cruz de Mayo (May Cross, held on May 3) celebrations there is no dancing to tambores, as the songs to the cross are more religious in nature.

The other main folk music style is the gaitas music of Zulia, which is usually heard only at Christmas, although in Maracaibo it is played all year. Gaitas is Spanish for bagpipes, but there are no bagpipes in Venezuelan gaitas music, which is played on cuatro, maracas, and the odd-looking furruco, a drum with a stick attached, played by rubbing the stick, which makes a very distinctive sound. Modern gaitas is played on electric keyboard and bass guitar by groups such as Guaco and Maracaibo 15, and competes with salsa and merengue at parties and discos in the run-up to Christmas.

SIMÓN DÍAZ—VENEZUELAN FOLK

LEGEND

Tío Simón (Uncle Simon), as he is known to his fans, is considered a national treasure in Venezuela. For many years he hosted a children’s show that promoted folk traditions, humor, and songs. Born on August 8, 1928, in Barbacoas, Guarico State, he is famous for his renditions of folk songs known collectively as joropo. His most famous composition is “Caballo Viejo” (“Old Horse”), which became a huge international hit for the Franco-Spanish group the Gipsy Kings after they renamed the song “Bamboleo.” He also recorded a very popular version of the country’s unofficial anthem “Alma Llanera” (“Llanos Soul”). Over a career spanning more than sixty years, he singlehandedly rescued for future generations the traditional working songs of the Llanos called tonadas, reinterpreting them with spare arrangements that bring to life the daily chores of the cattle ranch.