THE most important points to be considered in the selection of a shotgun are pattern, durability, balance, and general appearance. Good pattern, or, to be more concise, an even distribution of the shot charge, is easily secured today. Occasionally one does see a gun that makes a bad, patchy pattern; but in the old days, forty years or more ago, the position was reversed. Then the good shooting gun was as much of a rarity as the poor one is today. Of course, we are talking of well-made weapons, not necessarily expensive ones, but the output of reputable manufacturers.

This is partly due to the popularity of the choke bore; the cylinder is just as hard to make so as to give a good even distribution of shot as it ever was, but few of them are now called for in comparison with the quantities of guns sold. Generally one will order a full choke and modified, or a modified and improved gun; and any amount of choke, however slight, as it tends to restrict the size of the killing circle, will close up to some extent what might otherwise be an irregular pattern, so that it will pass unnoticed by any but the most critical sportsman.

However, the chief reason why there is now so little likelihood of unsatisfactory shooting is the improvement in the methods of manufacture. Modern improvements in machinery, the tooling up for quantity production, and skilled mechanics specializing on certain parts, have done more for the modern American gun than any other thing that we know of can possibly do in the future to advance the foreign weapons.

In considering the question of durability one naturally first thinks of the method used to fasten or bolt the gun so that it will not shoot or wear loose in the joint. And that is where we easily surpass our overseas competitors. A loose gun is an abomination, and even the fifty-dollar American gun will stand more shooting and general hard usage than most of the highest grade of British guns built by the best makers.

Mechanically, the most successful method of fastening a gun is the rotary bolt, such as is used with variations, on the L. C. Smith, Fox and others; not because it attempts to minimize the wear, which is impossible when two metal surfaces are constantly grinding together, but because it takes up all wear and keeps the gun tight forever.

The only exception to this system of bolting among our best double guns is the Parker, and that weapon is made with a care and precision that place it on a par, grade for grade, with some of the best foreign guns.

English makers have in almost every case refused to use the rotary bolt, and the long frames that we have adopted, because it makes the gun somewhat harder to open and close, which is a poor excuse for not adopting a better method. Consequently, some of their guns are double under-locked by means of two under lugs and a sliding bolt, have an extension cross-bolt and Purdey side clips, and still they shoot loose, despite the fact that they invariably use lighter loads in their game guns over there than we do; while a hundred-dollar Smith or Ithaca will remain tight for a lifetime.

Either a gun must be made with a bevelled hook, bolting through the extension rib so as to take up all wear automatically, or it must be so carefully constructed of the best material and so perfectly fitted that there is no opportunity for free play between the parts that will allow them to wear in time.

It is easily seen that if built on the first principle, a gun can be made at a reasonable figure that will remain just as tight as the most expensive weapon, but if the latter method is adopted a durable weapon can only be secured at a high price. In consequence, the British weapons in anything but the highest grades do not begin to compare with our rougher machine-made guns in this all-important point of durability.

The machine-made gun will eventually supersede the hand-made or semi-hand-made gun even in England, as it is unquestionably superior to them in anything but the best grades. The first step in this direction is the gun just produced by the B. S. A. Guns, Limited, and it will undoubtedly make itself felt shortly.

In justice to them, however, we must admit that the British guns are generally better finished and of superior balance to our American guns, grade for grade, in all but those costing $400.00 or more. This is natural, as their weapons are at least completed by hand in almost every case and consequently have a smoothness that is lacking in any strictly machine-made article. And their method of finishing allows for a more perfect correction of the balance than is possible in an entirely machine-made article.

The British makers will build a gun to order in any way that the purchaser desires—with Anson and Dealy side locks, top lever or under lever if preferred, to cock on the breaking or the closing of the gun, with a round or square cross-bolt, dolls-head, wedge bolt, or without any extension rib fastening if so desired, with side clips, intercepting sears, and detachable locks; any style of rib, raised, matted, swamped, or flushed and plain, and goodness knows how many different kinds of single trigger and ejector mechanisms to choose from. Lastly, the gun is bored, stocked and engraved to suit the taste of the buyer. This spells individuality from start to finish and despite the sturdy quality of our product, the American manufacturers have got to learn to do likewise or they can never hope to overcome the demand for the British product by those of refined taste.

It is extremely unlikely that the present generation will ever see them sell again at the old prices. Shooting appears every day to become more and more the rich man’s sport. Many believe that the present prices are entirely uncalled for, but we must remember that 75 per cent of the cost of production in the manufacture of firearms is labor—skilled labor of the finest kind—and the skilled laborer has become used to a scale of living in the past few years that it will be very hard indeed to get him away from. However, the sportsmen of this country are very much more fortunate than those abroad, where the cost of firearms has always been so much higher than it is here and where they are now becoming prohibitive for any one but a wealthy man.

The demand in the British Isles has always been for high-class guns. To a great extent shooting in England is limited, if not strictly speaking, to the rich man, at least to the upper strata of the middle class, and the little fellow in England, whether it is clothes, firearms or other things, invariably tries to ape those who can better afford to pay for the best than he can.

As the demands in the past have been for handmade guns, the British manufacturer has, of course, catered to it just as our American makers have turned out great quantities of cheap guns to meet the demand on this side of the water, the result being that in Great Britain the cheap guns which are purchased there have to a great extent been imported from Belgium or Germany, and they are indeed all that the word cheap implies. The cheap Belgian gun made for export was at one time sold in great quantities in this country, but since the advent of really good machine-made guns, the sale has fallen off year by year, until practically the only foreign gun brought into this country is the first-grade hand-made double, built by the best British makers and supplied to the wealthy class of American sportsmen, who can afford to pay the price demanded for them, plus the duty.

Before the war, sixty guineas ($300.00) would buy a gun by one of the best British makers, which is the last word in gun fitting and finish. Today, eighty to a hundred guineas are paid for the same gun, and second-hand guns by such masters as Purdey, Lang and others, are bringing more than they were made for, before the war. Unless one is buying a hand-made gun by one of the best makers, he is far better off with a well constructed machine-made gun than with one of the second-class or third-class hand-made or semi-hand-made guns of Great Britain. The arguments made by some of the British writers against the machine-made gun are that it will not stand up under the excessive strain imposed upon a gun in shooting driven birds, as the game is shot in England, that it will be poorly balanced, may not be safe, and will of necessity wear out and shoot loose in a very short time. This shows conclusively that the British writers are not at all familiar with our moderate priced American machine-made shotgun. I have shot for several years a couple of first-grade English shotguns, not because they are harder shooters than many American guns that I have owned, costing much less money, but because I appreciated the finer things in gun making which were hard to get here, but I also appreciated the stability and hard shooting qualities of the American guns. I have seen double barreled hammerless guns by two of our most popular makers, one costing $45,00 and the other $90.00 (before the war), which is certainly cheap, that have been shot upwards of thirty thousand rounds on salt water, using 3¼ drams of powder and 1¼ ounce of shot, and yet are as strong and tight as the day they were made, and have never been returned to the factory for a penny’s worth of repairs. With all due respect to the art of Purdey and Lang and other English makers, we can defy them to show a better record than these.

FIELD GUNS

There is a great deal of discussion at present as to what constitutes the most sporting and efficient gauge for field use, and while I have no desire to appear as a reactionary in the eyes of my readers, I must admit that personal contact with a great many sportsmen in the field has convinced me that despite the charm of the small bore, it is not as efficient an all-round game gun for the average man as the twelve bore. One of the reasons for the popularity of the twenty bore in America is that the gun makers are not in the habit of producing twelve bore guns as light and handy as those usually demanded by the European sportsmen, consequently we have been drawn to a smaller weapon to secure a lighter one.

A twelve bore weighing 6¾ pounds is just as efficient a weapon as the average unnecessarily heavy American field gun which weighs from 7¼ to 7½ pounds. The recoil is a little bit heavier when full charges are used but I find as years go on that we do not expend as many cartridges in a day’s shooting as we used to, and consequently recoil is not such a serious obstacle and due to the fact that we have fewer opportunities to fire shells than we used to, we naturally wish to shoot them with the best effect when we have the opportunity.

As I look back at the shooting in central New York when I was a boy and compare it with the rough shooting that is afforded there today, I notice that the shots are increasingly difficult. Even woodcock, that close lying bird, usually flushes wilder than the exceptional bird did twenty years ago. In those days, it was not an uncommon thing to flush eight to ten ruffed grouse in a single covey, most of which would get up intermittently, affording ample opportunity for the gunner to reload—while the dog pointed one bird after another.

Today the same birds will get up twenty-five to forty yards from the guns and not one in ten will lie for the point. We really need more powerful guns today than we used a few years ago. Despite this, I frequently shoot a twenty bore gun, not because I have any mistaken ideas as to its actual efficiency but because of what I might describe as its psychological charm. There is a pleasure in knocking down birds when you know that you are unduly handicapping yourself. Also I have a lot of guns—a twenty bore for special work including quail shooting is one thing, a twenty bore for all-round field work is another.

I know of nothing more delightful in the quail stubble, to use over good pointers, than a light handy twenty gauge gun, bored about half choke in the right barrel and full choke in the left, but this same gun would be a serious handicap in the hills of Pennsylvania, New York and New England, on woodcock and grouse, or even in some parts of the South where the quail are more apt to be found in the woods than in the stubble.

For such usage, an improved cylinder right barrel with a modified left is undeniably an advantage, but due to its wider spread the improved cylinder barrel must be about twelve bore in size to handle successfully 1¼ ounce of shot and when birds are wild, a charge of this weight is necessary to insure a pattern sufficiently thick to kill at forty yards from an open bore tube. Whereas I use a twenty bore when the occasion permits, I have never been deluded into believing that it is just as efficient a weapon. It is not and it never will be.

In the near future, as I suggest in Chapter VIII, it may become as powerful as our present day twelve bore and therefore become increasingly popular in the field through the same cause, but the twelve bore can also be increased in power. In my opinion, the perfect field shotgun is a light, well-balanced twelve gauge double barrel of not over 6¾ pounds in weight with 28-inch tubes, equipped with an automatic ejector, single trigger if possible and bored improved cylinder in the right barrel and about sixty per cent choke in the left.

There is nothing more absurd than for the sportsman to go forth into the field, armed with a gun that is full choke in both barrels as so many do today, be it twelve, sixteen or twenty; yet there are many men who should know better who are thus handicapping themselves from year to year; and generally the novice who is buying his first gun, and is not fortunate enough to have an experienced sportsman to advise him in his choice, is so equipped by some. irresponsible and thoughtless clerk in the store where he makes his selection.

There is nothing that will lower the old hand’s estimation of the sportsman’s experience more than to hear him declare what a terrible close shooting weapon his new game gun is. The experienced man as a rule has passed through the choke bore stage as a small boy outgrows his knickers. He will tell of the finish and balance of his pet; the locks, weight, and loads that he uses; he may even talk on trigger pull, but close shooting never—because it doesn’t shoot close; if it did he wouldn’t own it.

Sudden popularity is apt to lead to unreasonable extremes, and there has been an increased demand for choke bores from year to year until it has come to such a pass that it is a great deal easier to enter a sporting goods store and get a gun that will shoot too close than it is to secure one that will scatter too much. The best shot in the world could not do good shooting consistently on quail or woodcock in thick cover with a full choke gun, yet many who are not even passably good shots will stubbornly persist in trying to do so.

I have found that the best game shots invariably avoid the use of full choke when afield and reserve them for their proper place in the duck blind or at the traps. What they seek is a gun that throws its charge with the greatest evenness of pattern, and when they secure such a weapon they stick to it. This is equally true with many of our best professional pigeon shots. You will find in many cases that they prefer a slightly modified choke (65%) gun to an extremely close shooting (80%) one, provided that it consistently shoots as nearly perfect a pattern as possible.

In almost any small community that you visit you will hear of at least one gun that has a wonderful reputation for killing at long range. Whenever I have heard of such a gun and have had the opportunity, I have requested a chance to target it. And strange to say almost invariably it proves to be a cheap, poorly bored gun that gives a bad patchy pattern. Of course a gun that bunches its shot and places three or four pellets here and there is a hard killer when it hits. For if a bird is struck by four or five pellets of shot in a space that could be covered by a five cent piece, it is pretty liable to drop at almost any old range. But how often does the owner miss for every hit that he makes, and attributes it to his own poor judgment.

The craze for full choke field guns is slowly dying out, and the favorite in England is rapidly growing in popularity here. This is the improved cylinder. It is a cylinder-bore choke about .006 or even less, which does not alter the cylinder pattern to any perceptible degree, yet in some unknown way tends to give the desired effect of an even distribution of the load, without a ragged edge.

I do not seek to condemn the choke gun for use where it is practicable, for its many advantages cannot be denied. It is quicker, and its velocity is greater; it will kill further because of this increased velocity and closer pattern, and its penetration is better. A full choke gun will shoot No. 5 shot at 50 yards as hard as No. 6 shot is thrown from a cylinder bore at 40 yards. But the choke bore does not properly belong to field shooting, as it decreases your killing circle almost by half. At 40 yards the killing circle of the choke is 23 inches, while that of the cylinder is 40 inches. At the average distance fired at in bird shooting the game, if hit hard, is plastered with shot from a choke bore. Also the cylinder bore strings its load out further, which in some respects is an advantage in crossing shots. The man that gains a reputation as a good shot in the brush is not a putterer who pulls up behind his bird and draws across its line of flight until he has made what he judges to be the proper allowance. This style of shooting may do in a duck blind but it will never do for grouse or cock shooting.

The expert throws his gun to his shoulder like a flash at what he considers the proper distance ahead of the game and as the butt squarely hits the shoulder the piece is discharged. For this style of shooting the cylinder bore gun with its wide circle and longer column of shot has an advantage that no amount of skill will overcome.

I firmly believe that if a man has to choose between a full choke and a true cylinder gun for all-around shooting that the cylinder would be the most practical, as fully 75 per cent of the shots in the field are under thirty yards, and consequently the gunner would bag a larger percentage of game.

Some years ago I picked up a beautiful seven pound field gun in a sporting goods store at a very reasonable price. The gun was a beautiful weapon in every way and the mechanism was perfect. However, I hesitated, as the barrels were 30 inch and both full choke. But the price was half what the gun had cost and the salesman was a good one, so I fell for it, assuming that it would be all .right if scatter shells were used in the brush, and it would give the added advantage of close shooting when the birds were wild; but my chief fault in bird shooting is that which most gunners suffer from, shooting too quickly, and I have never seen game so wild that a cylinder would not drop them in the hands of a fast shot.

Considerable difficulty was experienced in securing brush shells in out-of-the-way places when the supply on hand ran short. Standard loads then had to be used until brush shells could be secured, consequently in the interim the score dropped about 20 per cent and most of the game bagged was ruined. The next season, after many misgivings and wakeful nights, the right barrel was bored out to improved cylinder. The improvement was so noticeable that the following year the left barrel was also bored cylinder. Since then they have been cut down from 30 inches to 26 inches and the gun laid aside for rabbits and woodcock, on which it is a terror.

If you have been using a close shooting gun in the field and returned this season dissatisfied with your work, have your gun bored out a little next season and you will probably be so pleased that you will be willing to let the far-off birds get away in future and make up for it on the close ones, with the old cylinder.

The single trigger is not a new idea, and the invention cannot be rightfully ascribed to any one gun-maker, as the system was successfully applied to double-barrel pistols a century ago. There is even evidence that the idea was put to practice over two hundred years ago, as a British collector of antique arms has in his possession a double-barrel, wheel-lock gun of that date actuated by a single trigger. However the idea was never successfully worked out until about 1880. The first patent was applied for in England in 1864, and since then hundreds of them have been granted, most of which have been abandoned.

W. W. Greener made a double-barrel hammer gun operated by a single trigger in 1875; to this day he does not urge their use, as he does not consider any single trigger mechanism can be relied upon not to go wrong in use. The reason why they have not been accepted more rapidly by up-to-date sportsmen can undoubtedly be attributed to the fact that a number of gun-makers in their eagerness to place one on the market have offered single triggers which when put to the test did not stand up, and as a result their sponsors have given them up in despair and they have all received a bad name to the rank and file of gun users.

At the same time the many advantages of the single trigger cannot be denied and in time they are sure to be more generally used. The most important of these to my mind is that there is only one best length of stock for every one. If a gun-maker was to supply us with a gun that was an inch too long or too short, any of us would think that he did not know his business, yet the shifting of the hand to operate two triggers must alter the length of the stock at least one inch. With a single trigger gun this trouble is eliminated once the proper length of stock is procured.

Also one does not have to shift the hand to fire the second barrel, which tends to induce greater speed in manipulation and accuracy as the aim is not altered so much. Another point in its favor is that it tends to do away with cut or bruised fingers, which are often the cause of so much unpleasantness when shooting a light gun that has a severe recoil, and this is a common cause of flinching which ruins many a good man’s score. Also, there is sufficient space between the trigger and the guard if the rear position of the trigger is used to permit one to shoot with heavy gloves on in severe weather, and no matter how much one may dislike to shoot that way, it is often a blessing to be able to do so. What these advantages mean to a sportsman can only be judged after a fair trial in the field.

It is evident, however, that the single trigger in the simplest form has to accomplish the work of the human finger automatically, which necessitates the use of springs and consequently increases its liability of getting out of order, and serves to complicate what in some cases is already a far too intricate mechanism; and, as the operation depends upon recoil to function, which is an extremely uncertain quantity, there is the constant liability of a balk or a double. Nearly all single triggers are equipped with a regulator which is generally placed beside the trigger guard and which allows the use of either barrel at will. It is impossible to operate this quick enough after a bird has flushed, and as a result if the sportsman is shooting a gun bored choke and cylinder, he will often have to shoot the choke barrel when he wants to use the cylinder and vice-versa. Of all the patents issued for single triggers there are really but three systems upon which most of them are based, which may be called the “Three Pull System,” the “Timing System” and the “Recoil Regulated System.” The idea of the first of these is, that after the first barrel is discharged there is a second or involuntary pull on the part of the shooter which is caused by the recoil of the gun. When the hammer (or in a hammerless gun the tumbler) falls it releases a slide, which due to the second or involuntary pull engages the sear of the second barrel, and on the third or second voluntary pull this barrel is discharged. In shooting, of course only the first and the third pull are noticed. The weak point in this system is that some men hold their guns so tightly that the second pull is eliminated and as a result when the second conscious pull is made to fire the second barrel, the gun is balked.

The recoil system is operated by a loose piece which is independent of the gun, and when the gun is discharged it jumps back on the recoil and gets in the way of a further trigger movement until the recoil is all over. Then it swings back and brings the firing lug in contact with the sear of the second barrel. The fault here is that some sportsmen pull the second barrel so quickly that the loose piece has not time to function and the result is a double. It can readily be seen from this that most of the single triggers will not suit all of the sportsmen that would like to adopt them, and each one must decide for himself. Personally while I value their advantages high enough to pay the additional expense involved, and as the pursuit of feathered game often takes me far from the beaten paths, or a repair shop, I do not care to complicate the mechanism of what is now a simple action. All of the reputable manufacturers have refrained from putting out a single trigger under their names until they had one that could be fully depended upon and as a result there are very few of them offered. The only one put out by our best makers is the L. C. Smith, and beyond question it is the best on the market anywhere.

What has been said regarding the single trigger applies in a measure to the automatic ejector also, for when they first came out many manufacturers, in their eagerness to get one on the market, offered to the public auto-ejectors that would not stand up under the severe strain of field service, and they gained an unsavory reputation that it has taken a long time to dispel. But most of the good patents have now run out, so that the gun-maker has a host of good ones to select from and nothing to pay for their use. Consequently, almost all of the makers of fine guns supply thoroughly reliable ejectors today, and no gun should be without one as the testimony in their favor is overwhelming.

Compared with the ordinary hammerless gun the automatic ejector is superior, because it performs the total withdrawal of the empty shells from the gun quicker than the best drilled expert could possibly do it by hand. When scattered birds are rising intermittently before the gunner, or in the duck blind, particularly for shooting the cripples, the time saved by an automatic ejector is of tremendous advantage; the gun can be loaded in half the time required with a non-ejector gun. Many sportsmen who have schooled themselves can get in four shots about as quick as the ordinary shooter would with a repeater. The auto ejector was first applied to double barrel shotguns by Mr. J. Needham in England in 1874, and Mr. Needham’s system still remains one of the best. Though seemingly numerous, the varieties of the ejector mechanisms are actually very few,—in fact, they may be divided into about two classes—those that are operated by the main spring like the Needham, and those that are operated by a separate lock situated in the forearm, of which type the Anson and Dealy is the most representative. When they are compared for strength and simplicity the great difference between the various makes is manifest. Simplicity is the first thing to be sought in an ejector and when one looks them all over he will quickly see that the only reason for the extreme complexity of those formerly in use was to get around the patents held by some other maker.

The ejector should always be made in two parts, so that each barrel operates independently of the other; otherwise when one barrel is discharged the good shell is thrown out of the gun, as well as the one that was fired; particularly is this true in a boat, as otherwise a lot of ammunition will be wasted. Many people think that an ejector is a strain on the action of a gun, but this is not so, as the shells only require a slight flip to throw them out of the chamber (which is all that the auto ejector does), for the ordinary ejector lifts them out of the chambers about a quarter of an inch and this loosens them if they are tight or jammed. Avoid the selection of an ejector that has many moving parts, as it increases the chance of its getting out of order. I am an enthusiastic advocate of the automatic ejector, but would not sacrifice efficiency by adopting a complicated one.

REPEATERS

There is another type of gun which we must now consider—which is the repeater. Some few years back, the increasing popularity of the repeating shotgun, and the introduction of the automatic appeared to have sounded the death knell of the old time favorite, the double-gun.

Sportsmen of the old school bemoaned the fact that the undeniable advantages of the multi-shot guns were rapidly putting the old favorite out of the running, and game protective associations sent up a howl of denunciation against the new instruments of slaughter, which it was predicted would soon exterminate the remnants of our rapidly diminishing game supply.

Sportsmen and game conservationists take a more liberal view of the “pumps,” and the “autos” today. They realize that despite the fact that in the hands of an unscrupulous game hog they will destroy more game, what we really want is better game legislation, and more rigid enforcement of the present laws. The greatest crimes against our once abundant game supply were perpetrated in the days of the muzzle-loader, before sportsmen had been educated up to the present-day view-point regarding game protection.

The results of the enforcement of more stringent game laws in the past few years and the enforcement of them has already shown most gratifying results, and will, as it continues, more than counterbalance the improvements in modern firearms.

It is extremely unlikely that the repeater will ever be regulated from the game field as an exterminator at this late date. Most sportsmen realize that this would be a foolish reactionary movement—no one would advise returning to the muzzle-loader as a means of saving game. What they want is up-to-date game conservation and game farms to combat the improved firearms and the increasing number of sportsmen. The repeaters and automatics have come to stay, but they will not, as was confidently expected, eclipse the double-barrel guns.

A short time ago I was told by a former director of one of the largest gun plants in the country that they discontinued the manufacture of their line of double-guns because they had confidently believed the day of the double-gun had passed, and they consequently devoted all of their attention to the repeater and the automatic. Today, realizing their mistake, they are seriously contemplating putting a new line of double guns on the market. Now the reason for the continued popularity of the double-gun is the undeniable lack of individuality in the pump or the automatic. The gun-crank rides his hobby hard and will never be satisfied with the humdrum, standardized, commonplace “pump.” The pump guns fill the bill for the rank and file who want a gun purely and simply for the purpose of killing game, and ask no more of it. They cannot find a more serviceable, reliable, hard shooting weapon, that will stand up under all of the misuse that they subject it to, than the pump. That is what the great majority want and the pumps will continue to be sold by the tens of thousands. But you may spend five hundred dollars on its engraving, gold inlay, and Circassian stock, and you will still have a highly camouflaged regulation pump.

The gun-crank, the connoisseur, the discerning sportsman, call him what you will, is never to be satisfied with this. He will own a pump, but the “pet,” the one that he brings out to show to his friends with a feeling of pride, will always be a double gun. In the double he has a far broader field for individuality, and can acquire an up-to-date thorough-bred among guns, refined, elegant of lines and of beautiful balance that will be a joy all of his life,—a gun that it is a pleasure to possess, that will express all of its owner’s ideas of what a fine gun should be, and one that meets with the needs of all of his little peculiarities in shooting. As proof of this, notice the ever increasing popularity of the single barrel trap gun.

Almost everyone acknowledges the superiority of the single barrel gun for clay bird shooting, and no gun made shoots harder, or closer, or stands up better under the severe strain imposed upon it in trapshooting than the repeater. The question of balance does not enter into the argument because a full magazine is never used in a repeater on the trap stand. Consequently, the balance of the gun is not altered. Thousands of pumps are used at the traps, yet the single barrel trap gun which a few years ago was a curiosity is becoming more popular all the time. It is again a matter principally of individuality.

There is undoubtedly not sufficient cause to call either type the better, as the advantage lies not so much in the fact that one has a single barrel and the other two, but the various methods of construction adopted to acquire the best practical results in both cause a varied difference in the results attained when in use. Consequently, each has its advantages and disadvantages. These I shall endeavor to point out, and leave it to the purchaser to decide which is the best suited to his individual tastes.

Undoubtedly, a single barrel is the quickest to align, as it is easier for the eye to sight down one barrel than between two. This is the reason why they are so popular among trapshooters. I have had many pigeon shots tell me they could break from 10 to 20 per cent more birds with a single barrel gun than they could with a double, as it is easier to judge accurately the lead necessary to connect with rapidly crossing targets.

It is hardly necessary to further consider the single barrel trap gun, for although they are considered by many to be superior for the purpose for which they are intended—trapshooting—and have all the elegance of proportion and balance of the double gun, few sportsmen would care to handicap themselves with the serious disadvantage of not having a second shot to fall back on in the field.

A point in favor of the repeater is that due to the receiver or frame which is about six inches in length, the sighting plane is much longer than on a double gun made with the same length of barrel.

Most of our best pigeon shooters are long barrels, not because of their greater killing range (which in these days of modern smokeless powder is to a great extent a fallacy), but because of the tremendous advantage in accuracy of the long sighting plane.

Many gun-makers advise their patrons not to use 26-inch barrel double guns because it is so hard to shoot accurately with them at any but very short ranges, but a repeater with 26-inch barrel has a sighting plane at least as long as a 30-inch double gun, and a repeater such as I used for several years, with a 32-inch barrel, had a sighting plane of 37 inches. However, such a long gun is out of the question for anything but duck or trapshooting.

One bad point in the single barrel guns is that as a rule they are extremely light in the muzzle, and the shorter the barrel, the more noticeable this is. For a man who swings rapidly or jerks his gun up quickly on the mark, this is a serious disadvantage, as it makes it very difficult for him to shoot steadily. And the extra amount of metal at the muzzle in a double makes it heavier at this point, and consequently easier to hold up on to the mark.

Sometime ago, I had the pleasure of shooting Dr. Carver’s old pigeon gun which was made specially for him by W. W. Greener. Dr. Carver shot this gun in matches all over the world and his records are famous. The barrels of this gun are fully one-thirty-second of an inch thicker at the muzzle than the tubes of any other gun that I have ever handled. It certainly seemed to me to be far too muzzle heavy, but it was remarkable how steadily it could be held on a fast crossing bird.

The demand for a gun with a single sighting plane that will allow two shots, together with good balance and appearance, has led some of the foremost makers of England, including Boss, Westley-Richards and Grant, to produce a double barrel gun with superimposed tubes. Those weapons are commonly called “over and under” guns. The advantages claimed for them are, that the vertical joining of the barrels placed the shells in a direct line with the center of the butt-plate and the recoil is carried back on a straight line instead of giving a side thrust, as does the ordinary double gun, thus lessening the recoil. The depth of the fore-end necessary on such a gun keeps the left hand out of sight—also there is the quick single sighting plane before mentioned. However, this type of weapon presents considerable difficulty in securing a proper locking system, due to the peculiar mechanical construction, and many of them have proved weak in this respect. Consequently, they have only been made at a cost that is prohibitive to the average sportsman. I have examined many “over and under” guns and found many of them rather wanting in this and other minor details. The chief trouble has usually been in the automatic ejectors. When the barrels are side by side, there is an equal leverage exerted on each ejector, but when they are superimposed as in the “over and under” gun, there is very much more pressure exerted on the upper barrel than there is on the lower one. This generally tends to weaken the upper ejector and I have seen many of these guns which gave considerable trouble.

In all fairness, however, we must remember that the double guns have been going through a process of evolution for over a century, whereas the “over and under” and repeaters are comparatively new ideas which will probably in time reach as high a state of perfection as the double has.

DUCK GUNS

Of course, the repeating gun has always been favored more in America for duck shooting than for field work, and this is natural. For American duck shooting, the repeater is really the logical weapon, whether it is hand functioned or automatic. Ducks are very apt to dive when wounded and hold on to grass on the bottom or steal away and then die miserably from privation and their wounds, and every good sportsman seeks to prevent this as much as possible. Often a bird will be quickly dispatched with a third or fourth shell from a repeating gun that would get away before a double barrel gun could be reloaded.

Abroad the repeater has never been well received. There has always existed a great gulf of misunderstanding between British and American sportsmen because of the radical difference in the type of weapons which they use, which clearly shows the ignorance of the lack of similarity between our shooting conditions and those existing across the water, all of which should be taken into consideration to fairly compare the effectiveness of our weapons and theirs.

For shooting over decoys, the repeater is undoubtedly the logical weapon in this country, whereas if we wish to reach out to greater distance as we frequently do for point shooting or pass shooting where longer range and more power is desired, a 10 bore double barrel of about ten pounds weight naturally is superior.

Within the past few years, a new type of weapon has come to the fore in England, known as the Magnum, and a later development of the Magnum type is the chamberless gun. These I will describe as briefly as possible.

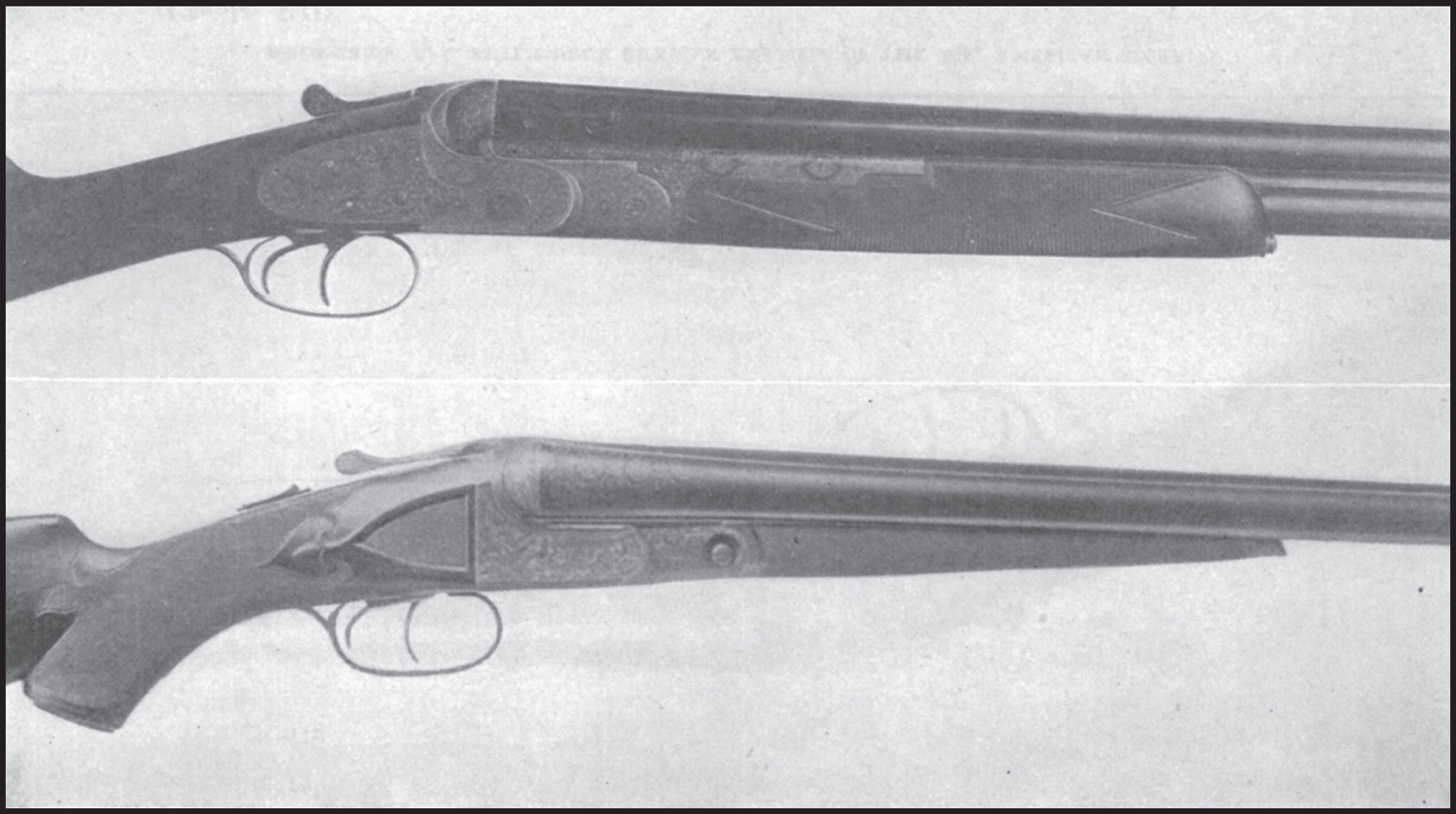

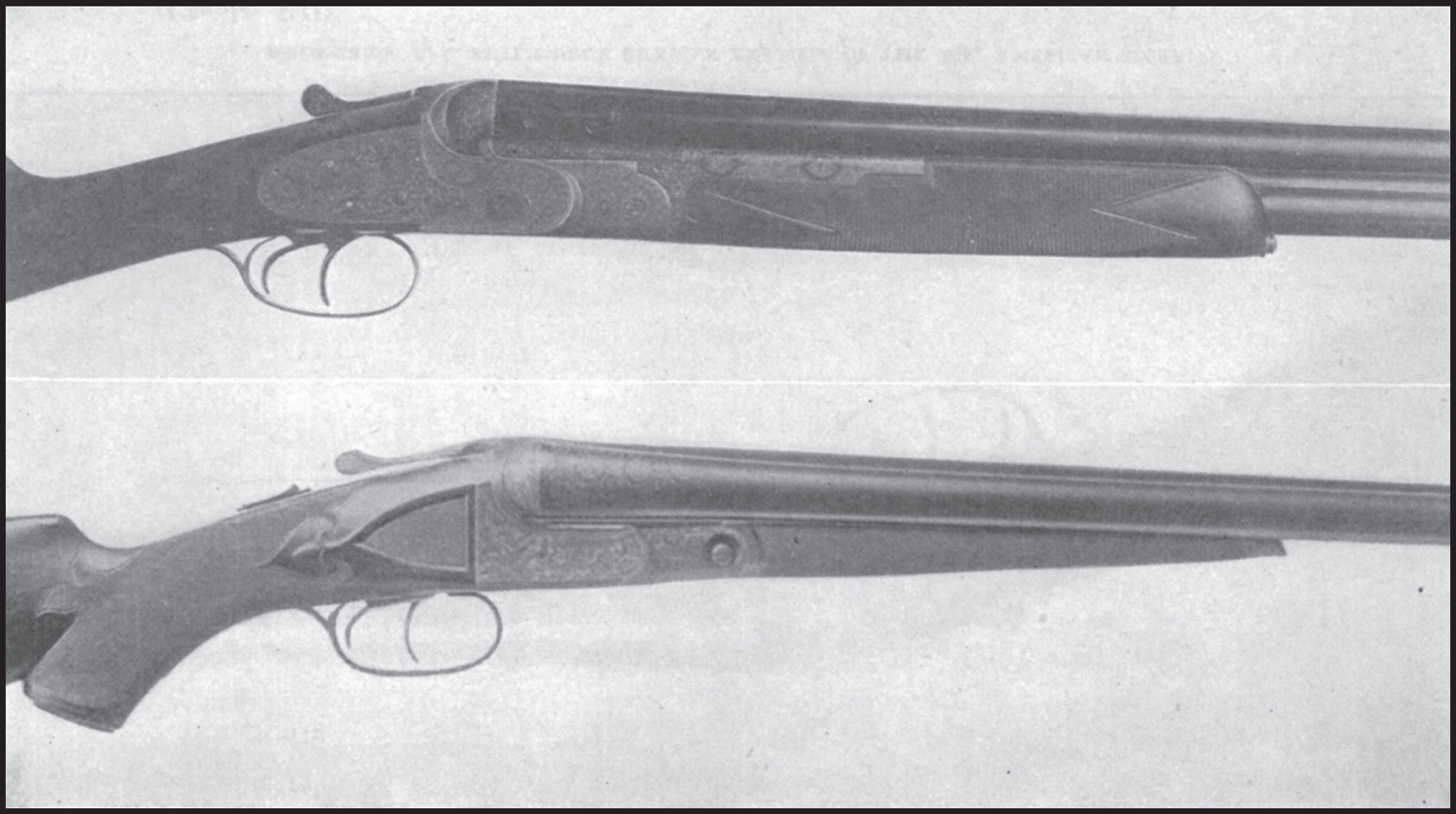

TWO THOROUGHBREDS.

Upper—“OVER & UNDER” BY BOSS, THE LAST WORD IN HAND-MADE GUN CONSTRUCTION (ENGLISH).

Lower—HIGH-GRADE DOUBLE BY PARKER BROS. AN EXAMPLE OF THE BEST MACHINE-MADE GUN (AMERICAN).

HIGH-GRADE L. C. SMITH DUCK GUN. AN EXAMPLE OF THE BEST AMERICAN WORK.

The Magnum is either a 12 or a 10 bore weighing from eight to ten pounds, which shoots a special brass cartridge known as a “Perfect.” These shells which are of very thin brass, tapering down to a paper edge at the crimp end, are from three to three and a quarter inches long, and naturally have a much greater capacity than the regular paper case which has thicker walls. They do not require as much wadding, as the end of the chamber is usually finished off with a square shoulder instead of a cone, or if a cone is used, it is not as deep as it would be in a paper case gun. The necessary resistance to attain the proper combustion of the charge (for which we consider a cone needed) is probably attained by the heavy shot charge, for these guns fire from four to six drams of bulk smokeless and from one and a half to two ounces of shot, according to the calibre. It naturally follows that as more shot is driven effectively from them than can be fired from a paper case gun, the pattern will be thicker plus a higher velocity and greater energy per pellet. Hence these weapons will continue to be effective at ranges where the standard paper case gun would be useless.

The chamberless gun is, as its name implies, without an enlarged space for the shell. The case goes into the true barrel, which has been enlarged from behind the choke down to the breech sufficiently to eradicate cone or shoulder. In other words, while the bore of a paper case 12 gauge is .729 and the bore of the chamber .800, in the chamberless gun the whole bore back of the choke is .800. Very elastic wadding is used to prevent gas leakage between the end of the case and the barrel. The advantage claimed for these guns over the already acknowledged superior Magnum is that the total absence of cone reduces the extent of shot deformation and friction within the bore.

It is claimed that the Magnum and the chamberless guns will kill at from eighty to a hundred yards, according to the weight and the size of the charge, in fact, the makers will guarantee them to do so, and while it is my opinion that the chamberless gun is built upon the right principle, I still believe that there are several flies in the jam pot.

To begin with, What constitutes a killing gun at one hundred yards? This is where a proper appreciation of the difference in our shooting conditions is worth consideration. Some authorities familiar with their methods have caustically criticized British duck shooting, and I believe, with some justice. It may be that no other methods would be successful over there than those practiced by the British wild fowler. I am not sufficiently familiar with their duck shooting to speak with authority. It is true that the Scottish, Irish and British coast is rugged and generally rocky, while the waters in the fall and winter are invariably rough. There are no great protected bays like those along our Atlantic seaboard so famous for the shooting that they afford on shallow and endless marshlands. Such waters as the Solent and the Norfolk Broads afford protection from the elements but in the main their shooting is confined to the mouths of small streams and unprotected headlands, where a battery could not float. Naturally, the shooting is chiefly at sea ducks and geese. Such birds as our golden eye, scooters and wedgeons are generally termed trash ducks over here. There is some shooting on inland waters for teal and mallard, but these are generally killed by flighting as they pass over and the decoy has been, as a rule, ignored. I cannot help feeling that our British cousins are grossly ignorant of the successful use of decoys in America, and because “it hasn’t been done” in the past, so to speak, have arbitrarily overlooked their usefulness. I am convinced that despite the difference between our natural conditions and theirs, decoys, either live or wooden, could be used to considerable extent, and better sport could be had by so doing. I have killed lots of sea ducks on the Atlantic coast with an ordinary 12 bore over decoys which could not have been lured within range of a four bore without them. Failing the use of decoys the Britisher has had to be satisfied with killing such birds as he could at long range and the methods adopted are sometimes ludicrous in the extreme to our Yankee eyes. With all due respect to the hardihood of the British wild fowler, braving the bitter cold and the chances of a watery grave in an all day effort to paddle his punt within 100 yards range of an unsuspecting flock of birds, so that he can let off a two bore gun into their midst, indiscriminatingly killing and wounding them, I cannot in respect for what my father taught me the word implied, call it sport. Slaughter it surely is. I have read Stanley Duncan’s book, and note the comment on his mighty cannon—a double barrel gun, weighing two hundred pounds with a one and a half inch bore, shooting 32 ounces of shot to the barrel. I have heard of records of upwards of a hundred birds being bagged from a single discharge of such a gun.

Thank Saint Hubert! Such killing has not been tolerated here for half a century, and never was in the name of sport. The market hunter is almost run to earth, and the four and the eight bore gun legislated out of existence. Yet these heavy shoulder guns are commonly used abroad. You may ask what all this has to do with the effectiveness of the Magnum gun. I am coming to that now. It will be seen from the above that the Britisher is inclined to judge the effectiveness of his duck gun largely by its ability to bring to bag indiscriminately some birds out of a flock fired into at longer range by the use of larger shot. The same gun might be quite incompetent of killing with any degree of consistency single birds at a much shorter range than that from which it would take toll from a flock. Consequently, as flock shooting is frowned upon in this country, I am inclined to believe that while the Magnum gun may have considerable range over that of our best paper shell guns, it would not be as much in our estimation as they claim. The 10 bore Magnum that might honestly be said to have a killing range of a hundred yards by British standards might not be good for over eighty-five by ours. Nevertheless, this is a distinct improvement well worth considering.

There is another important reason why the Magnum gun would not find such favor here, which is the question of shells. Naturally the Perfect brass cases are extremely expensive, and while one does not use a great many shells in the course of a day’s duck shooting by the British “bush whacking” methods, the case is entirely altered in America. It is true that one can save on this by reloading, but few of us care to go to this trouble, and the trouble is greatly increased when the number of shells required for a day’s sport is so much larger as it is over here. Also as the Perfect case is not made in this country, we would have to depend upon export for our supply, which is somewhat uncertain, particularly as I understand that the British shooters have been experiencing some trouble in getting them since the war, as the best brass shells were imported from France.

The British have always been intolerant of the automatic so popular in this country, calling it a machine gun fit only for the pet hunter, while at the same time they use guns that have been outlawed in America for years. They decry the man who shoots a repeating gun, and consider it unpardonable to use one, while they think it nothing amiss to hurl half a pound of large shot into an unsuspecting mass of wild fowl sitting on the water. I hold no brief for the automatic gun, many of the best sporting clubs in the country prohibit its use upon their waters, and while I personally use one for wild fowl I have no patience with one that does so for upland shooting; but I must say that I consider the man that brings down five ducks out of a passing flock with as many clean, well directed shots is practicing better sportsmanship than the fellow who bags as many or more by one discharge from a miniature cannon.

The popularity of the automatic and repeating shotgun in this country is directly attributable to existing conditions, just as the swivel gun is in England. Duck shooting in this country is usually indulged in on a pass at flight birds or over decoys, on the waters where the birds are coming in to feed. In either case the shots are usually at small bunches, pairs, singles. The wise man, over decoys, will allow the large flocks to pass knowing that if he does they are almost sure to come back in small detachments which will afford him an opportunity to kill a good number; whereas, if he fired into the mass he would at the best get but a few of them and scare them all away for the day. Such shooting calls for a fast handling weapon, with which one can easily pick his bird. If it has the advantage of several shots, it insures better chances for despatching cripples before they can get out of range and as the shell can be fed into the magazine, between shots, one is never caught with an unloaded weapon. Added to this, shooting in America is a democratic sport, and the poor man can get in a repeater a strong reliable weapon that will outlast in serviceability any double gun that would cost twice as much in England. The British call the repeaters and automatics clumsy and ugly weapons, in which the balance is constantly changed by the number of shells in the magazine. There is a lot of truth in this; even the most hardened champion of the repeating gun will admit the superiority in feel, balance and general appearance of a well made double gun over the best repeater, but surely they are as a summer zephyr in comparison with some of the heavy eight and even four bore shoulder guns used abroad.

If decoys are really impractical for most of the duck shooting in the British Isles, then unquestionably their Magnums are the proper guns, and even the eight bore is to be tolerated, but I cannot condone in my own mind the use of any weapon for any purpose that cannot be fired from the shoulder.

Likewise, the repeaters must be acknowledged as the logical arms for our methods of shooting, if one’s desire is to insure getting the limit with as little trouble as possible. When we need to reach out farther for them, as we do at times, then the Magnum, whether its efficiency has been exaggerated or not, would be the best choice were it not for the problem of shells, and consequently our best bet is still a ten bore of about nine pounds weight to shoot five drams of powder and an ounce and a half of shot. We can well afford to take a page from the Britishers’ book in this respect just as they could from ours in regard to decoys.