THE ever increasing popularity of the twenty gauge gun for field shooting leads me to believe that a few words relative to its past history would not be amiss at the present time. Most sportsmen seem to believe that the twenty gauge fad is an entirely new idea—the outcome of improved ammunition and more powerful powders—but this is really furthest from the truth. Of course, the earliest known sporting guns were crude affairs—and large bore by necessity, as they were loaded with any bits of metal by way of substitute for dropped shot, which was unknown. But in the closing days of the eighteenth century the shotgun became really a gun as we know it and judge its qualifications today and about that time the twenty-bore, double-barrel flintlock was extremely popular.

Most of the guns of such famous master gun-makers as Joe Manton were fourteen, sixteen and twenty gauge, and even twenty-four gauge were used and advocated by some sportsmen for shooting over dogs. Manton died when he was sixty-nine years of age, in 1835, and at that time was making, principally, eighteen and twenty gauge guns for his patrons. Yet, despite the fact that he was universally acknowledged to be the premier gun-maker of the world, the pendulum had begun to swing back in favor of the larger bores, and a little later we find Frank Forrester (William Herbert), about 1845, in his writings advocating the ten-bore gun for upland shooting in this country. Eights and fours were used for ducks and considered the only thing, and the old reliable fourteen was almost forgotten—and, although they were still made after the muzzle loader became obsolete it is difficult to secure cartridges for one today.

Now in our present reaction towards the small bore of bygone days we have overlooked the fourteen, sixteen and eighteen gauge in favor of the twenty, as a result of which there has been a greater call than ever before on our manufacturers for twenty-eight gauge guns, caused by the extremists who follow all radical changes. They are responsible in a great measure for all reactionary movements, and who knows but what our grandchildren will be using the sixteen and the forgotten fourteen and eighteen bore? And extolling its virtues, the latter bore is unlikely—but certainly the sixteen is a safe and moderate step for the average man to take.

Because we have only really advanced along certain lines—a close examination of a “best” gun by Manton or one of his contemporaries would be educating to the average American sportsman. I have had this opportunity and they leave nothing to be desired in balance, proportion and workmanship. Even in shooting against our open bore guns they will compare favorably.

The hang and detail of some of these old masterpieces that I have seen was equal to that of one of our best makes of today. Few Americans realize this because most of the muzzle loaders in existence in this country are not good examples of the early gun-maker’s art.

It is only in late years, that is when guns began to be made by machinery, that we made really good shotguns in this country in any number. In the old days high grade guns were not made here—but were imported from England, and most of the American shotguns were made by crude gunsmiths who purchased the rough barrels and locks in England and made the other parts themselves and put the guns together. Abroad many beautiful examples of the old gun-maker’s art, in perfect preservation, may be seen in private collections. The muzzle loader reached the apex of its perfection about 1830, and it was a finished product, just as the auto-ejector, single trigger, breech loading gun of today is a perfected type. As a muzzle loader it could not be improved further.

The early breech loader, on the other hand, was a new idea, and, while the principle was recognized to be superior, the guns, in their imperfect stage, were uncertain—faulty in pattern and not nearly as strong shooters as the muzzle loaders. This was responsible for the tendency towards large bores, which gave them a chance to compete against the more powerful muzzle loaders. The large bore breech loader won out against the small bore muzzle loader, not because it shot better—because in those early days it did not—but because it was so much handier. Finally they became the perfected gun of today, and our tendency is to return to the old favorite, the small bore of a century ago. This naturally brings us to the question of what the relative killing power of the standard gauges is today. This subject is so broad in its scope that it is impossible to go into it in detail in the space of a short chapter. There are so many important points to be considered that before we finished reviewing the case we would have compiled a book which most people would throw down in disgust before they half finished reading. We will, therefore, only consider the problem from the practical side.

One of the chief reasons why so many sportsmen are entirely at sea as to the actual killing power of various size guns is because it is almost impossible for them to make their tests with guns that are relatively of the same dimensions in every respect but calibre. They will collect a full choke 10 gauge with 32-inch barrels—a modified and cylinder 12 gauge with 28-inch barrels, and a full and modified 20 gauge of 30-inch barrel—or some other combination of calibre—choke, weight and length of barrel that are not proportionate. In a like manner their shells will vary. They will have 3½ drams, 1¼ ounce loads for the 10 gauge; 3¼ drams, 1⅛ ounce for the 12 gauge, and 2½ drams, ⅞ ounce for the 20 gauge, with possibly a variation in the size of shot.

This is manifestly unjust; whether we are comparing light field loads or heavy, long range ducking loads, the charges should in each case be relatively the same to the calibre of the weapon. It is idle to compare the pattern of a 3-inch, 20 gauge shell loaded with 2⅝ of powder and ⅞ ounce of shot fired from a full choke barrel with a 2⅝ 12 gauge shell loaded with 3 drams of powder and 1 ounce of shot fired from a modified choke barrel. Yet people do so every day and then marvel about the favorable showing the twenty made. One reason is that sportsmen are advised by the sporting goods dealer to use comparatively heavier loads in their new twenties to make them compare with the old twelve, and they do so unconscious of the fact.

In this way I have heard sportsmen argue that their specially loaded 12 gauge guns were so much stronger shooters than the old tens, which they used to use. They could easily procure 12 gauge shells loaded with 3½ drams of smokeless and 1¼ of shot from the local dealer, but they did not realize that a comparative load for the ten would be 4½ drams of powder and 1½ of shot. The dealer does not, as a rule, carry more than 3½ dram loads for the 10 gauge in stock, and one would have to wait a considerable time to get them from the factory, with the result that one uses the lighter loads. None of our munition makers supply heavier loads for a 10 bore than 4¼ drams of powder and 1¼ ounce of shot and this is a well balanced charge—but by no means as powerful as a good 10 bore is capable of handling. If we could get 3-inch 10 bore cases loaded with 4½ drams of powder and 1½ ounce of shot there would be more 10 bore guns in use today. But such loads would be unsafe in cheap, poorly constructed weapons and as the munition makers must protect themselves, we must suffer—for if we do not load our own cases we cannot get the full power and range out of a 10 bore weapon.

The 10 gauge gun loaded with 4½ drams of powder and 1½ ounce is considerably superior in killing power at long range to the 12 gauge, loaded with 3½ and 1¼ ounce of shot.

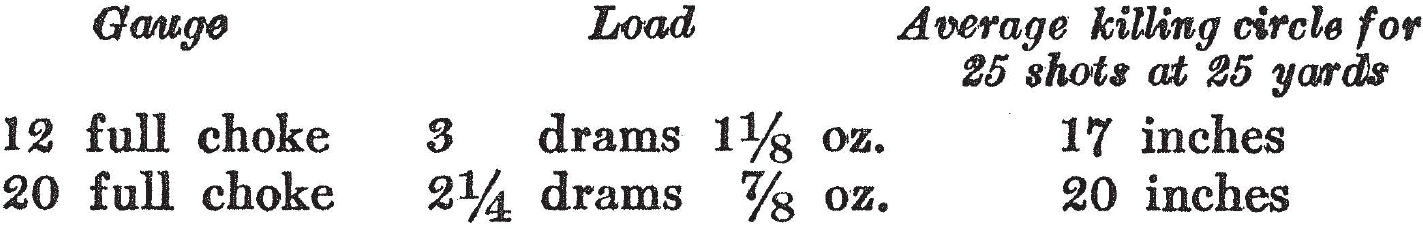

To begin with, it should be remembered that the basic fact underlying a fair test is that the deviation from true center of a given charge of shot at a given distance is practically the same, regardless of the calibre, providing that the percentage of choke in each barrel and the powder charge is the same. As an illustration the following table is shown. It should be noted that both guns are full choke.

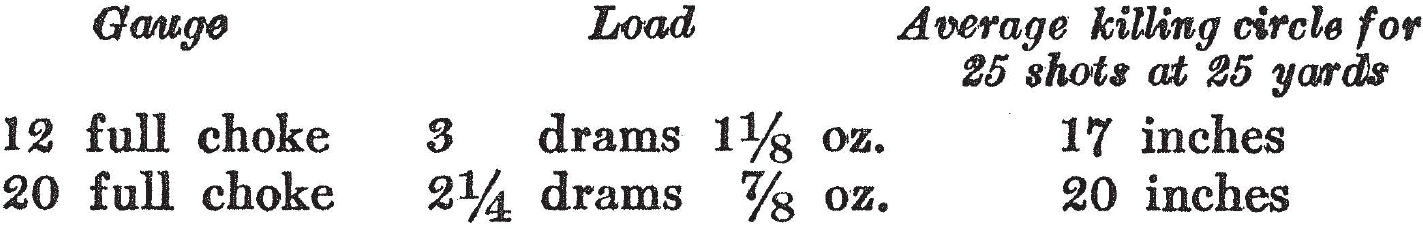

The slightly higher velocity of the 20 gauge in a measure accounts for the wider distribution, but also because a 12 bore can be choked satisfactorily up to 80%, whereas it is impossible to get good results from a 20 bore with greater than 70% choke. Working up from this we find that though the small calibre gun will give higher velocity with a given charge of powder and shot than a large bore would with the same load, the killing circle is about the same. The larger bore will, however, handle more powder and shot successfully, and if loaded in proportion to its bore will, consequently, put more shot into a 30-inch circle at 40 yards than a smaller bore, as the following tables show:

Consequently, as the distance is increased, the pattern will diminish in thickness and the 12 gauge will continue to give a pattern sufficiently thick to kill, due to the greater number of pellets in the load, at a distance at which the 20 with its lighter load would begin to be unreliable.

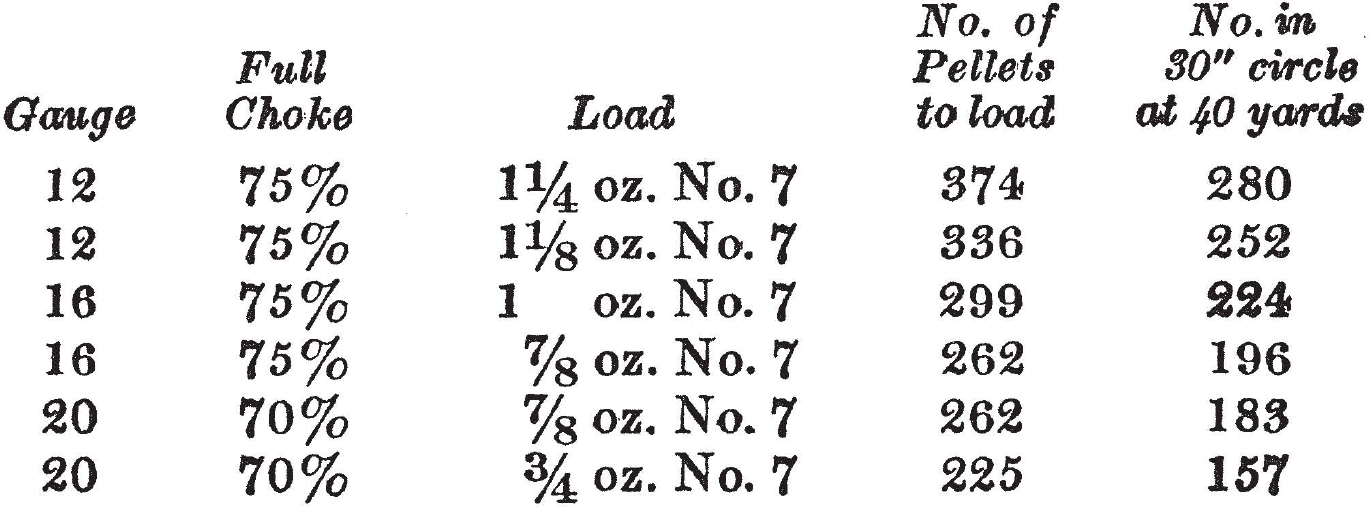

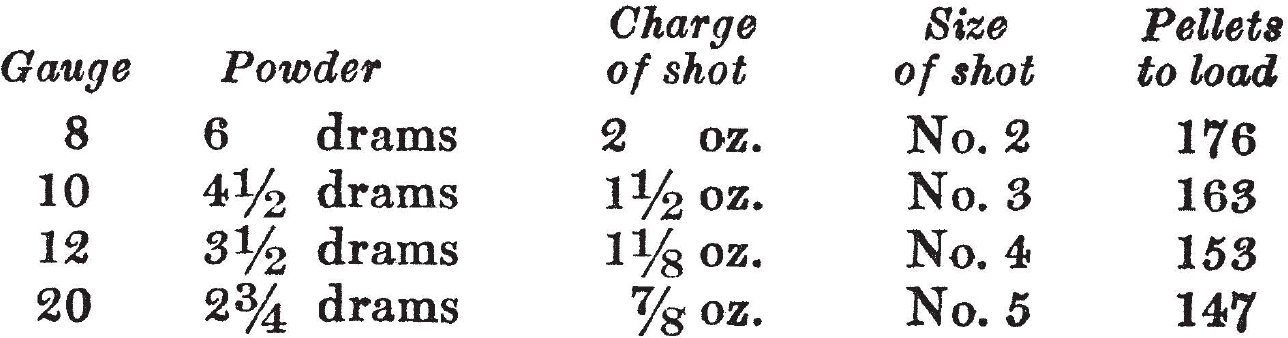

The following are the maximum charges from which the fullest benefit will be secured in the several size guns commonly used. In England (as mentioned in a previous chapter) specially constructed 10 and 12 gauge guns are built for even heavier charges, but the average gun would be overloaded and not give the best results if the charge were increased.

The size of shot given in each case is that which I have found to be the most satisfactory for long range shots at ducks in the various gauge guns mentioned. It is noteworthy that in each case the large gauge guns, if bored the same percentage of choke, will throw a greater number of pellets into a 40-inch circle at 30 yards, despite the fact that the size of shot is larger than that used in the next smaller size gun. And the larger shot will, of course, carry further and kill at greater range. With the loads given, the guns mentioned are dependable at the following ranges; the 8 at 80 yards; the 10 at 60 yards; the 12 at 50 yards; the 20 at 40 yards. It is not meant that they will not kill further, but they are not certain to at greater distances, even though the aim is correct. Most sportsmen believe that a full choke 12 is certain at 60 yards, but careful patterning will prove that this is not true. The average man overestimates the distance at which he kills his game.

For all practical purposes, it is safe to say that, loaded with the same size shot, the 20 gauge will do the same work at 35 yards that the 12 gauge will at 45 yards, and the 10 gauge will at 55 yards.

It is not my intention to belittle the 20 gauge gun; it has its sphere and for field shooting, due to its handiness, which allows the sportsman to get on his birds quicker and, consequently, kill them closer, it will hold its own. But it has not the killing range of the large bore guns and will not supersede the 12 for general purposes and more particularly for long range shooting. It has been shown that the 20 gauge does not shoot any harder than the 12 gauge, as its spread is fully as great as that of the 12 and, consequently, the pattern must be more open at the longer ranges, due to the reduction in the charge of shot.

The old idea was, that to get a long range, hard-shooting gun, one had to have long barrels on a heavy frame to shoot large charges of powder. This is a mistake, and it seems incomprehensible that, with all the experiments made, and interest taken in the shotgun, American sportsmen should not have discovered it before.

The British sportsman recognized this fact years ago and today you will see few guns used on the other side weighing more than 7¼ pounds and sixty per cent of them will be 6¾ pounds. Some years ago there were a good many 4¾ pound, 12 gauge guns built to shoot light 12 bore charges in England. It is by no means urged that a 12 bore should be as light as these “feather weights” were, because recoil was unpleasant from them, even if only a few shots were fired; the contention is merely that a light 12 bore (6½ pounds) will kill as well as a heavy one, provided it carries the same charge and load and its barrels are as long as the heavy gun tubes.

Be moderate in your selection, choose a 12 gauge weighing 6½ to 6¾ pounds and you will have a gun that is but little if any heavier than a serviceable 20 gauge would be, and that in the hands of the average marksman would be tremendously more efficient, as it would shoot just as hard as an eight or nine pound 12 gauge would if loaded with the same charge. Mr. F. E. R. Fryer, one of the finest shots in England at driven game, uses a pair of 6¼ pound, 12 gauge guns with 1⅛ ounces of shot and has been frequently seen to have three birds dead in the air at one time, having the second gun handed to him. To be sure, a 12 gauge gun weighing only 6½ pounds has to be of the best to stand 3¼ drams of smokeless powder, for a cheap gun would soon go to pieces under the severe strain; but cheap, poorly constructed guns should be avoided in the first place, and need not be considered here.

If one is using a light 12 gauge, with correspondingly light loads, he might as well use a 20 gauge as he has no advantage over it; in fact on the contrary, he has less power. Many people will say that the recoil from a light twelve with heavy loads will be too severe, but a man who knows how to handle it and use the full charge in a light 12 gauge will suffer no ill effects.

The matter of handling the recoil is largely one of educating yourself to doing so properly. The amount of shot used in the shells has a great effect upon this, as the recoil from 3¼ drams of powder is much greater if 1¼ ounce of shot is used than if 1⅛ ounce is used. The pattern is, of course, more open if only 1⅛ ounce is used but this can be remedied by using smaller size shot, the killing power of which will be just as good, as the velocity of the load is greatly increased.

Owing to the style of holding there was no discomfort from the recoil shock, as one would expect. At first I found that the recoil of heavy ducking loads in such a light gun was a severe strain, especially in warm weather when lightly clad, and the birds coming in fast to the decoys. I had a recoil pad fitted to the gun but this did not relieve matters much as the shock of the recoil is delivered to the entire system, and not only to the shoulder which is bruised; for how else would shooters suffer from “gunner’s headache” which is not caused, as some think, by the powder gases. To relieve myself of this strain, I developed the habit of shoving forward on the forehand, that is, instead of holding the gun back on the shoulder tightly with both hands I hold it firmly with the trigger hand and shove forward against the forehand with the left hand. In this way the left arm acts as a shock absorber and most of the recoil is caught in the hand.

Far from impairing the aim, once one becomes used to this style of holding, he will find that it improves the shooting, at least it did in my case, and in no other way could the gun be held so firmly. This should be of particular value to ladies and men of light weight.

The best shot at wild fowl I ever knew was using, until a couple of years ago, a heavy imported 12 gauge. Finally he purchased a high grade American field gun, full choke and weighing only 6¾ pounds, two pounds less than the ducking gun. Taking it out on Long Island Sound one day, as an experiment, he found it killed as far and hit as far as the old “duck gun” and he has used it ever since.

In “Frank Forrester’s Field Sports,” edited in 1848, Herbert says, “For any person that can afford it, and would take the trouble of having different guns for every species of sport, for summer duck shooting I should recommend a gun not to exceed 26 inches for length of barrels and 12 gauge, with a weight of 6½ pounds, only. For autumn shooting, the gun I would recommend would be 7½ pounds weight, 30 inches of barrel, this, I believe, being the most killing proportion that can be adopted, and by all odds the best gun for general shooting.”

I quote this to show the advanced ideas of the greatest expert of a departed day, at a time when choke bores and smokeless powder were not known, and the small bores were being rapidly superseded by the large bores. No better advice than this can be given today. It is admitted that the light 20 gauge guns are of little value and that to be serviceable they must weigh 6 pounds to 6¼ pounds. Why then handicap one’s shooting with the little gun when a 12 gauge, which is much more powerful, can be secured which weighs little more? Of course if, in the name of sport, one wishes to handicap his own shooting, it is quite commendable to do so, but to induce others to do likewise do not insist that the little weapon is more powerful—it is not and never can be. It is felt by many shooters that the 10 will outlive its present unpopularity as a fowling piece and come back to its own in the near future, for no matter how much the efficiency of the 20 bore and other gauges may be improved in the future—the 10 bore can be improved proportionately.