As NASA discovered each new problem with the telescope, scientists worked hard at finding ways to solve it. If a problem could not be corrected from the ground, it became part of the planning for the repair mission. The solution to some of these problems involved designing and building new instruments that could be installed aboard the telescope. Installing these new instruments would be the work of a team of astronauts on NASA’s first repair mission in space.

Detailed plans for the mission to repair the Hubble Space Telescope began in the summer of 1990. The long list of repairs took shape through 1991 and most of 1992. Because of the huge cost of these repairs, the stakes for the repair mission were high. NASA’s reputation, and possibly its future, was on the line. Much would be gained by the mission’s success, and much would be lost if it failed.

For the all-important mission, NASA selected one of the most experienced crews of astronauts it had ever assembled. Their training began more than a year before the mission, which was scheduled to launch in December 1993.

“I’m not overconfident,” said astronaut Story Musgrave. “I’m running scared.” Musgrave was the mission’s payload commander, and he was responsible for coordinating the spacewalks that would repair the telescope. He knew how difficult a job the mission was going to be for him and the crew. “This thing is frightening to me. I’m looking for every kind of thing that might get out and bite us.”1

Musgrave had been a surgeon before he came to NASA. When asked why he gave up surgery to become an astronaut, he quickly answered, “Why, so I could operate on the Hubble, of course.”2

Dick Covey was the mission commander, in charge of the overall success and safety of the mission. Kenneth Bowersox, whom everyone called Sox, would back up Covey as shuttle pilot.

Mission specialist Claude Nicollier would operate the shuttle’s robotic arm, or Remote Manipulator System (RMS). He would use the arm to grab and release the telescope. During the repairs, a fellow astronaut would be attached to the end of the arm. Nicollier would move the astronaut around the shuttle’s payload bay in the same way a firefighter is moved when in the bucket of a cherry picker.

Two teams of spacewalkers would make the repairs to the telescope. Musgrave’s spacewalking partner would be mission specialist Jeffrey Hoffman. The other spacewalking team would be mission specialists Thomas Akers and Kathryn “K.T.” Thornton. All four had conducted spacewalks on previous missions.

Image Credit: STScI / NASA

The team of astronauts chosen for the daring repair mission had to undergo extensive training. In this photo, astronauts Steven Smith and John Grunsfeld train in the Goddard Space Flight Center, working on a backup of an electrical section of Hubble for a servicing mission in 1999. The astronauts are wearing special suits to protect the sensitive equipment from particles that could interfere with its performance.

After months of exhaustive training, the team of astronauts was ready for the mission. In the darkness at 1:00 A.M. on December 2, 1993, the crew rode to the launchpad at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida and climbed aboard the space shuttle Endeavour. Strapped into their seats, they waited through the countdown as the launch drew nearer. Once again, everyone involved with the Hubble Space Telescope was watching closely.

Endeavour sat on the launchpad, lit up with spotlights. Only seconds to go before liftoff.

“Ten . . . nine . . . eight . . . seven . . . and GO for main engine start,” said the public-address announcer. “Five . . . four . . . three . . . two . . . one.” At 4:27 A.M., the shuttle’s engines ignited, lighting up the night as it thundered off the pad into the early morning sky. “And we have liftoff . . . liftoff of the space shuttle Endeavour and an ambitious mission to service the Hubble Space Telescope.”3

In a matter of minutes, Endeavour and its crew were in orbit around Earth. They were now chasing the telescope. Over the next two days, Endeavour would gradually close the distance between them. The astronauts spent this period checking all the shuttle’s systems and getting used to the sensation of weightlessness.

Early on the third day, Endeavour’s crew caught its first sight of Hubble. Commander Dick Covey and pilot Ken Bowersox guided the shuttle closer to the telescope.

“Now it’s all eyeballs and hands,” Bowersox said.4 He knew the control thrusters of the shuttle had only enough fuel for one try at getting close enough to the telescope. They had to get it right.

Claude Nicollier took his place at the controls of the robotic arm. Endeavour drew closer and closer to the telescope. Nicollier reached out with the arm, and its claw gently grasped the Hubble Space Telescope.

Commander Covey said to Mission Control: “Endeavour has a firm handshake with Mr. Hubble’s telescope.”5 Covey’s announcement caused a sigh of relief in the Mission Control room. The telescope was in place in the shuttle’s payload bay. The long and challenging task of repairing the telescope could now begin.

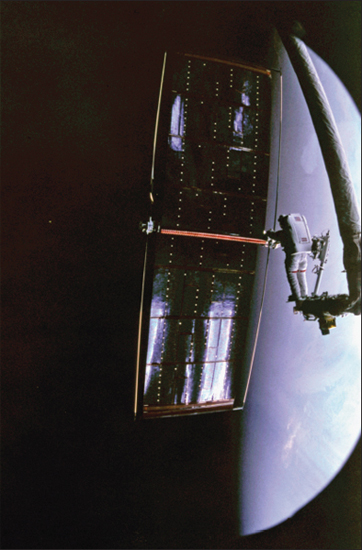

Image Credit: NASA Marshall Space Flight Center

Astronauts Story Musgrave and Jeffrey Hoffman were tasked with the mission’s first spacewalk to repair the telescope’s faulty gyroscopes. This photo taken from Endeavour on December 2, 1993, shows Musgrave during his spacewalk.

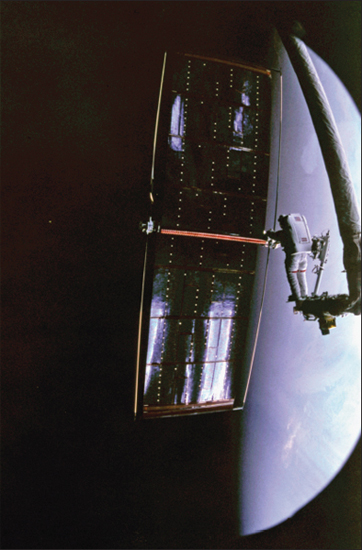

Image Credit: NASA Marshall Space Flight Center

Astronauts Story Musgrave and Jeffrey Hoffman, perched atop foot restraints attached to Endeavour’s robotic arm, repair Hubble during a spacewalk. The two astronauts had no trouble replacing the gyroscopes, but struggled to get the panel doors closed at the bottom of the telescope.

The following day, Story Musgrave and Jeffrey Hoffman helped each other slide into their cumbersome space suits for the repair mission’s first spacewalk. Their task was to replace the telescope’s faulty gyroscopes. Gyroscopes are instruments that are used to keep vehicles such as boats, airplanes, and spacecraft steady. The telescope needed the gyroscopes to keep it steady when scientists pointed it in the direction where they wanted to look. Three of the telescope’s six gyroscopes had failed and needed to be replaced.

Musgrave and Hoffman entered the air lock and closed the hatch behind them. The air lock is a room in which air pressure is slowly reduced to what the astronauts experience outside the protection of the shuttle. This had to occur before they opened the other hatch and floated out into space. The astronauts kept themselves attached to the payload bay by metal cables. Musgrave slowly made his way toward the telescope, which stood upright at the rear of the payload bay. Hoffman attached his feet to the end of the robotic arm. Nicollier then moved Hoffman and the arm toward the telescope.

Musgrave and Hoffman opened the panel doors near the bottom of the telescope. The two astronauts worked well together and had no problem replacing the gyroscope mechanisms. But when they were finished, Musgrave discovered he could not get the panel doors shut again. One of the doors was sagging.

Image Credit: NASA Johnson Space Center

In this photo, astronaut Kathryn Thornton releases the old solar array into space during the Hubble repair mission. After discarding the broken instrument, Thornton and Thomas Akers installed the new solar arrays to the telescope.

They tried different tools to force the doors shut but none of them worked. Musgrave suggested using something called a come-along. This tool had a crank that would pull the doors together and hold them. With the come-along holding the doors together, Musgrave used his hands to push them shut.6

The incident with the doors showed the astronauts that not everything would go perfectly. They would have to be clever and resourceful to overcome some of the mission’s unexpected problems.

Musgrave and Hoffman’s next task was to prepare the equipment for the removal of the solar arrays on either side of the telescope. The arrays were designed to roll up like window blinds. The first array rolled up perfectly. The other array had been warped. It would not roll up. The safest thing to do with the broken array was to throw it out into space, away from the shuttle. That job would be done the following day by Tom Akers and Kathy Thornton.

Akers and Thornton pulled on their space suits and went to work on the mission’s second spacewalk. Thornton was at the end of the robotic arm. She steadied the solar array while Akers disconnected it. He had to be very careful not to bend the pins that held the electrical connectors. If they were bent, they could not be used to attach the new solar arrays. Without the solar arrays, the telescope would have no power.

Akers slowly and carefully disconnected each bolt and pin as the shuttle orbited into Earth’s night side. Finally, the solar array was free. Thornton alone held the solar array. She had to hold it perfectly still. If it began to move around, it could hit the telescope and damage it. While Thornton held the array, Nicollier used the robotic arm to move her and the array slowly away from the telescope.

“OK, Claude, real easy,” she said.7

At that moment, they were still on the night side of Earth. They needed to wait until daylight when the entire crew could see clearly, in case the solar array threatened to float back against the telescope when it was released. Thornton had to hold the solar array at the end of the robotic arm for several minutes, waiting for daylight. As Endeavour orbited onward, Thornton’s partner finally saw light appear on Earth’s horizon.

“I think I see sunrise coming, K.T.,” Akers said.8

Endeavour and its spacewalkers orbited into daylight.

“OK, Tom,” Musgrave said from inside the shuttle. “Tell K.T. to go for release.”

“OK, K.T. You ready?” Akers asked.

“Ready,” Thornton said.

“Got a go for release,” Akers said.9

At that moment, Thornton released both of her hands from the array. “OK. No hands,” Thornton said. Bowersox immediately used Endeavour’s control thrusters to steer the shuttle away from the floating solar array. The crew watched as the solar array floated safely away from the shuttle.10 The solar array would stay in orbit for some time before eventually burning up in Earth’s atmosphere.

Thornton and Akers successfully attached the new solar arrays. They crawled back inside the shuttle for a well-deserved rest.

The third spacewalk was an important one. The task for Musgrave and Hoffman this time was to replace the Wide Field Planetary Camera, or WF/PC, with an improved version called WF/PC 2. This was probably the most delicate operation of the mission.

Hoffman held the large camera in his hands as he stood at the end of the robotic arm. He had to hold the camera very steady while Musgrave carefully removed the protective cover from the mirror. The mirror of the new camera was just several inches from the faceplate of Musgrave’s helmet. If he touched or bumped the exposed mirror even slightly, the mirror would be knocked out of alignment—a disaster that would ruin the camera before it ever took its first picture.

Image Credit: STScI / NASA

Astronauts Story Musgrave and Jeffrey Hoffman were charged with the most intricate operation of the mission: replacing the Wide Field Planetary Camera with an improved version, WF/PC 2. This photo shows one of the astronauts removing the old camera during the repair mission.

Musgrave moved out of the way slowly and precisely. He then helped Hoffman guide WF/PC 2 snugly into its slot in the telescope. The camera was in place, and the third spacewalk was another success.

It was Akers and Thornton’s turn again. Their task for the fourth spacewalk was to install a device that was of central importance to the telescope. It was called COSTAR, which stood for Corrective Optics Space Telescope Axial Replacement. This was the device that scientists had designed to correct the flaw in the telescope’s primary mirror.

COSTAR was a metal box the size of a refrigerator. It contained a set of ten movable mirrors, each of which was no larger than a thumbnail.11 Once COSTAR was installed in the telescope, it would deploy these mirrors. The mirrors would reflect the primary mirror’s light in a way that would correct its flaw. In other words, although they could not correct the primary mirror itself, they could correct the path of light reflected from it.

Nicollier guided Thornton forward at the end of the robotic arm, where she held COSTAR in her hands. However, it was so big that she could not see where she was going. Akers served as her eyes. He hummed as he helped Thornton guide the mechanism into place. Nicollier was listening at the controls of the robotic arm.

“It was good to hear Tom humming,” Nicollier said later, “because we knew when Tom was humming things were going well. And Tom was humming most of the time!”12

Akers and Thornton slid COSTAR into its tight fit inside the telescope. The major repairs of the mission were completed. They were almost home free.

On the fifth and final spacewalk, there was a bit of drama. Musgrave and Hoffman were wrapping up the repairs when a small screw escaped from Musgrave’s tool bag. If it was lost, there could be trouble. The space shuttle is a complex machine. Even something as small as a loose screw floating inside the shuttle’s payload bay during reentry could spell serious disaster.

They had to catch the screw. Musgrave was attached to the end of the robotic arm, and Hoffman was tethered to it. But the screw was floating down and away from them into the payload bay, where it would become impossible to find. Nicollier saw the screw’s glinting light from his place at the robotic arm’s controls. He quickly began to guide Hoffman and Musgrave down in its direction. Nicollier was moving the arm much faster than usual, because he knew it was important to capture the tumbling screw.

Image Credit: Time & Life Pictures / Getty Images

Astronaut Kathy Thornton services equipment on the Hubble Space Telescope during the fourth spacewalk of the repair mission. Her task during this operation, along with Tom Akers, was to install COSTAR, the device that would correct the flaw in the telescope’s primary mirror.

Hoffman reached out his hand as they chased it. Down and down toward the payload bay they went.

Just as Hoffman’s feet were about to bump into the side of the payload bay, he caught it. “I have it,” he said.

“Okay, arm stop,” Musgrave said quickly.13

The screw was returned to the bag. With a sigh of relief, Musgrave and Hoffman went about their work and completed the repairs.

On the following day, the newly repaired Hubble Space Telescope was released back into orbit. The crew of Endeavour had done their best on the telescope. They had conducted five spacewalks—more spacewalks than any other American astronauts or Russian cosmonauts had ever conducted on any single mission. It was an impressive record. After eleven successful days in space, they were ready to come home.

Endeavour made a night landing at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida. As far as the astronauts knew, nothing had gone wrong on their mission. But they did not yet know if their mission had been a success.

NASA scientists and astronomers around the world once again focused their attention on the Hubble Space Telescope. All waited to see if the repairs had worked.