The penis is often considered as a separate entity from the rest of the body, sometimes with its own life and a name. But of course the penis is very much a part of the whole body; it is not autonomous. The penis is under the control of the nervous system—a combination of voluntary and involuntary innervations. By examining the structure of the genitals in detail, we can better understand the interactions by which men protect them.

The penis consists of a root located in the perineum (the area between the legs that we sit on; in women it contains the vaginal opening) and a free, normally pendulous portion, termed the corpus or body, which is completely enveloped in skin. It consists of three bodies of erectile tissue that extend through most of the length of the penis. The upper two bodies, the corpora cavernosa, consist of highly vascular connective tissue or fascia. They are firmly attached to the margins of the arch of the pubic bone. They do not extend to the end of the penis. The lower body, the corpus spongiosum, contains—in addition to the vascular fascia—the penile urethra or duct coming from the prostatic urethra. The glans or head of the penis is the expansion at the end of the corpus spongiosum. The base of the corpus spongiosum is firmly attached to the fascia of the perineum or urogenital diaphragm (Fig. 7-1).

Erection is controlled by the autonomic nervous system affecting the blood vessels of the penis. The parasympathetic fibers (the relaxing part of the involuntary nervous system) in the nerves of the corpora cause a dilation of the small arteries. This dilation increases blood flow into the blood sinuses, resulting in a distension of all three corpora. This increased volume of blood applies pressure to the veins leading from the sinuses and decreases the venous flow from the tissue. After ejaculation or time and lack of energy, it is assumed that the sympathetic fibers or involuntary stimulating nerves constrict the arteries, reducing the blood flow into the sinuses and allowing the blood to flow back into the veins. The penis can then return to its flaccid state.

Figure 7-1

Structure of the penis (photo credit 7.1)

It has been assumed that the dorsal veins that lie on top of the corpora cavernosa are the major venous factor in erection. Over the years I have observed that there are veins on the sides of the penis that also serve in that function. In many cases pressure on the left side of the base of the penis will produce an erection. Pressing on this side can also help increase the rigidity of the erection during sexual activity.

The penis is often referred to as a “muscle.” There is no muscle in the penis itself except for the smooth muscle of the blood vessels. There are muscles that can be considered extensions of the perineum that are located at the base of the penis. The bulbospongiosus arises from the perineal body and extends in a Y-shape around the base of the corpus spongiosum. The muscle aids in the emptying of the urethra, after the bladder has expelled its contents, the final spurts. It can be used to stop the flow of urine. There may be some contribution to erection.

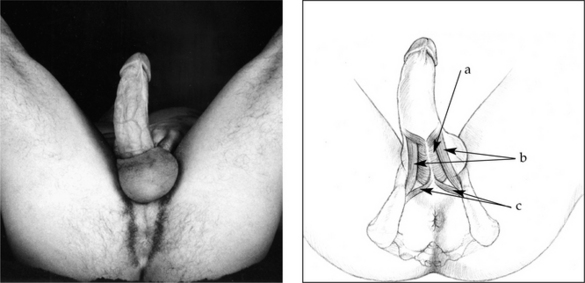

Figure 7-2

Muscles of the penis

(a) bulbospongiosus m. (b) ischiocavernosa m. (c) transverse perineal m. (photo credit 7.2)

The ischiocavernosa is a pair of muscles that covers the base of the corpora cavernosa. They arise from the V-shaped ramus of the ischial bone, extending back to the ischial tuberosities, the sitz bones (Fig. 7-2). These muscles may play a more specific part in maintaining erection of the penis. With palpation, it often feels as though these muscles become glued to the bony rami, resembling the texture of beef jerky. This lack of tone will make them relatively non-functional.

The perineum or urogenital diaphragm fills the area between the ischial rami (the bony platform we sit on). Midway between the tuberosities at the end of the rami is the perineal body. This is a fibromuscular node with fascial and muscular attachments in front to the bulbospongiosus of the penis and behind to the external sphincter of the anus. It also receives fibers from the transverse perineal muscles that make up most of the perineum, and from the levator ani or pelvic diaphragm (Figs. 7-3).

Figure 7-3

Muscular connections in the perineal region

(a) bulbospongiosus m. (b) perineal body (c) transverse perineal muscles (d) external anal sphincter (e) ischial tuberosity (photo credit 7.3)

The perineal body, therefore, serves as an interface between the anus and the penis. Habitual contraction or flaccidness of the area will affect its structure and function. Constant tightness would pull the anus and penis into the body, resulting in constipation or difficulty in initiating urination. Lack of tone of the muscle and fascia could lead to incontinence for urine and/or feces.

The levator ani or pelvic diaphragm (deep to the perineum) extends from the inner surface of the pubic bone to the coccyx. It has some connection to part of the external anal sphincter, to the perineal body, and possibly to the base of the bulbospongiosus. This is referred to as the floor of the pelvis (Fig. 7-4). This is the bottom of the abdominal cavity. Potentially, the so-called “abdominal breathing” can be felt this far down.

In front, there are two ligaments that suspend the penis. One, the fundiform ligament, arises from the linea alba (midline) of the sheath of the rectus abdominus and wraps around the penis in a sling-like arrangement. The suspensory ligament arises from the pubic symphysis and also wraps around the penis (Fig. 7-5). Tightening of the abdominal muscles by sit-ups and other exercises is often considered a cosmetic need in our culture. This can create a shortening of the abdominal muscles between the pubic bone and the umbilicus (belly button) where the muscle and fascia have become habitually tense. Since the suspending ligaments are a continuation of the rectus abdominal fascia, such tightness will result in a constant pull upward and inward of the penis. This can lead to a deadening of the feeling in the penis, especially since the breath response will not reach that region.

Figure 7-4

Pelvic and urogenital diaphragms

(a) urogenital diaphragm (perineum) (b) pelvic diaphragm (levator ani) (c) external anal sphincter (photo credit 7.4)

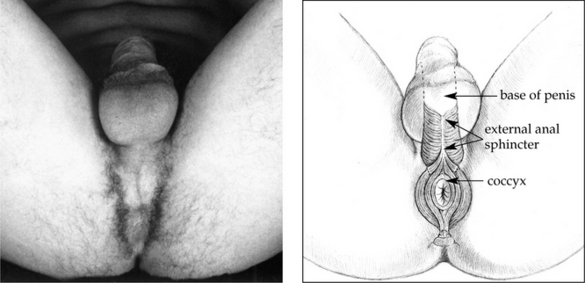

It is estimated that one to three inches of the penis may be internal, sometimes buried in the layer of fatty tissue over the pubic bone. The penis is not a muscle—it cannot be “pumped up” like the skeletal muscles of the body. It may become smaller with lack of use. The length of external penis may be determined by the flaccidness or rigidity of the muscles behind and above the penis. The tone of the abdominal muscles will determine the lift of the suspending ligaments. The tone of the muscles of the perineum (urogenital diaphragm) and/or the pelvic diaphragm (levator ani) may cause a pulling in of the base of the penis. A tight anus will pull on the base of the penis through the connection of the external sphincter with the perineal body (Fig. 7-6). Any or all of these conditions translate into a loss of feeling and a problem with function.

Figure 7-5

Suspending ligaments of the penis (photo credit 7.5)

Figure 7-6

Muscular connection of the penis to the coccyx (tailbone) (photo credit 7.6)

Figure 7-7

Diaphragms of the body cavity (photo credit 7.7)

Fascial connections from both the pelvic and urogenital diaphragms will extend to the fascia of the obturator internus muscle, from there to the fascia of the iliacus muscle, to the fascia of the abdominal oblique muscles, and to the fascia of the respiratory diaphragm. The genital area does not exist in isolation (Fig. 7-7). A lack of elasticity of the diaphragms will affect the tissues above and vice versa.

Figure 7-8

Male genitals (photo credit 7.8)

The testicles lie on either side of and slightly behind the penis. They are located in the scrotal sac, the skin of which is continuous with the skin of the penis. Each testicle is suspended by a spermatic cord that contains the blood and nerve supply of the testes and the spermatic duct (ductus deferens). The cord crosses the pubic bone and enters the external opening of the inguinal canal. It continues diagonally upward through the inguinal canal to the internal opening into the body cavity. From there the spermatic duct angles down to enter the prostatic urethra at the base of the bladder (Fig. 7-8).

The internal opening or internal ring of the inguinal canal is the site of inguinal hernias. These seem to be related to tightness in the surrounding musculature and fascia. The internal ring can be considered a “weak” area. It is formed by an opening in the tendonous extensions of the abdominal oblique muscles with no supporting muscle involved. Tightness in the psoas and the abdominals will pull the tissue apart, enlarging the opening so that a loop of the gut can slip through and become “herniated.” The symptoms of incipient hernia have often been relieved by reducing the tightness of the surrounding musculature, thereby reducing the pull on the internal ring.

The scrotal sac is divided into two compartments by a septum. On the surface one can see the “scar” or raphe continuous with that of the underside of the penis. This indicates the dual origin of the scrotum. Generally the left testicle hangs lower than the right. It has been speculated that this occurs because the left side descends first before birth. Also, the spermatic cord frequently adheres tightly to the side of the penis on the left causing the penis to point to the left. It has been estimated that 75 percent of men hang to the left (Fig. 7-9).

The wall of the scrotum contains the dartos muscle. This is the extension of the subcutaneous fascia of the abdominal wall and may be an extension of the external abdominal oblique muscle. This is non-skeletal muscle, responding to involuntary control. It causes the folds of the scrotum and will respond to stimuli such as cold or sexual arousal by shrinking up to the body wall. The cremaster muscle seems to be the muscle of the spermatic cord. Its contraction will draw the testes up to the body. There seem to be two mechanisms in the involuntary response to cold and other stimuli—one compressing the scrotal wall and the other raising the testicles. Generally they will act together, but they can act individually. There is a “cremaster reflex” on the inner thigh. When that area is stimulated by light touching, the testicle on that side will be drawn up by the cremaster muscle. The dartos muscle is not affected by this reflex. Sexual arousal will generally cause the testicles to be pulled up to the body and the scrotal sac will tighten, forming many folds in the wall (Fig. 7-10).

Since normal body temperature is too warm for proper sperm production, the function of the scrotal muscles is to aid in the regulation of the temperature of the testicles. When it is hot, the testicles will hang loose, allowing for cooling away from the body proper. In the cold, the testicles are drawn up close to the body for warmth. Studies in England have shown that men who consistently wear tight briefs have a lower sperm production than those men who wear looser underwear. Today when a man has a fertility problem, it is common for the doctor to recommend boxer-type shorts.

Figure 7-9

Variations of penis

Note that one of the six (A) hangs to the right, and one of the six (B) is uncircumcised. Chosen randomly, the models above roughly approximate the normal variations in the U.S. Size variation is also apparent. (photo credit 7.9)

Figure 7-10

Muscles of the scrotum (photo credit 7.10)

The penis does not exist in isolation. Its fascia is continuous with that of the perineum, the rectus abdominus muscle, and the adductor muscles of the inner thigh. This was demonstrated in a water skiing accident that happened to a friend of mine. The skis were pointed outward when he started off. He held on to the rope, attempting to bring the skis together. His legs spread further and further apart until he felt a “snap” in his groin area. Too late, he let go of the rope. The results were not only stiffness in the upper leg muscles and difficulty sitting down (especially on the toilet), but also a large, purplish haematoma over the pubic bone area that extended into the shaft of the penis. Such results of a pull on the inner adductor muscles affecting the penis can be explained by fascial continuity.