8

I WALK HOME from Joon’s feeling slightly queasy about Trivia Quest. I sprint past the neighbors’ to avoid the Axi-Tun alien. I can’t wait to take refuge up in my room. To have some quiet and think this whole contest idea through.

But the minute I open our front door, there’s trouble: Cal is fist-pumping and leaping around the living room like he’s just scored a winning touchdown.

“YES!”

He’s about to knock over a floor lamp.

“YES YES YESSS!”

“NO!” Mom says, diving for the lamp with one hand and swiping for the long, thin package Cal’s holding with the other. “I swear I’m going to shoot your grandfather! In a manner of speaking.”

“What’s going on here?” I say.

“Gramps gave me the hunting rifle I wanted for my birthday!” Cal shouts joyfully. “A .22!”

Gramps comes shuffling in from the kitchen, clutching his cane in one hand and a coffee cup in the other. “Darn straight I did,” he says. “The boy’s fourteen, Jane! Ain’t nothing wrong with it!” He glares at Mom from under his wiry gray eyebrows. “Let the boy grow up! Cal’s more than old enough. Hell, even Stanley here’s old enough for a little target practice. OOH-yah.” Gramps ends a lot of sentences with “OOH-yah,” because he’s from what he calls “dang near indestructible Norwegian farm stock.”

“Target practice where? We don’t have forty acres of cornfields out back, like you did, Dad,” Mom says, shaking her head and frowning.

Gramps really misses his cornfields. And hunting. He loves going on about it and about how great life was back in the simpler time of the early Pleistocene, or whenever it was he grew up. The menfolk would go deer hunting every November, ice fishing every February . . .

But Mom’s a total pacifist. She hates the thought of killing living things for sport. And I have to say, I’m with her. Anyway, right now Mom is yelling, and Gramps is yelling, and Cal is aiming the rifle out the window where some tall guy—it must Liberty’s uncle, I guess—is innocently walking down to his mailbox.

Mom swipes the gun from Cal’s hands. “End of story. I’m locking it away right now.”

“But—I’m fourteen!”

“Not another word!”

Cal’s face is flushed. “Well . . . who else is going to man up around here?” he bellows.

Mom wrinkles her nose and jolts her head back. “What on earth are you talking about?”

“Who’s gonna protect us?” Cal’s fuming. “You’re always working. Dad’s ditched us. Gramps is too old. Who’s the man in charge?”

Mom’s eyes bulge, and she starts rumbling like she’s a volcano about to erupt. “Who on earth in this day and age says there has to be a man in charge, Calvin Fortinbras? I’m working two jobs, running this house, feeding you, clothing you, doing everything around here—and there has to be a man in charge? What on God’s green earth do you think we need protecting from? Has Gramps got you thinking you’re Daniel Boone, living in the wild frontier, with all this gun nonsense?”

I feel like I should do or say something. But I don’t know what. So I just stand there, frozen, clutching at my Trivia Quest notes. Wanting everyone to stop shouting.

“What about the coyotes?” Cal shouts. “Every night, they keep coming up the canyon!” Cal grabs at his greasy brown hair. “And you won’t let me do anything about it.”

Mom’s mouth opens and shuts but nothing comes out. Then she looks down at the gun in her hands. She storms upstairs, where we hear the slamming and locking of closet doors.

Cal slams out the back door.

Gramps, muttering, starts shuffling back to the kitchen. He waves his hand around as if he’s had it with the whole business.

And I’m still standing right where I came in, clutching my comics in my cramped fingers, my mouth hanging open.

What the heck am I supposed to do now?

Mom solves the problem. “Stanley!” she shouts from upstairs. “GO FEED THE CHICKENS!”

The coop’s past the garden beds, alongside the detached garage—a green, slanty-roofed wooden hut with eight hens. Gramps built it for us after he got here last year, and Dad, when he came over to help, teased him. “Keeping chickens? Why don’t you just mail all the neighborhood coyotes an engraved dinner party invitation,” he’d joked.

But somehow, miraculously, we haven’t lost a chicken yet.

I head out there with a bowl of kitchen veggie scraps and whistle for Albert Einstein, who is snuffling in the underbrush. “Stay away from there, Albert Einstein! That’s coyote territory!”

He totally ignores me.

“ALBERT EINSTEIN!” He is too busy circling and snuffling. Finally, he chooses a primo piece of real estate and squats. When he’s done, he won’t come back to me, so I have to drag him by the collar.

He’s lucky he’s at least good-looking.

I put down the scrap bowl and I’m just turning to pry open the chicken feed bin when I hear a small cough—and what do you know, there she is again, the Axi-Tun warrior girl, standing by the corner of our garage.

Liberty.

Great.

“So, why you are yelling at the top of your lungs for Albert Einstein?” she asks. “Urgent physics questions?”

I point to the dog, who stares at me with his glazed, buttonlike eyes. “That’s his name. It’s ironic.” I grab a scoop of pellets, pick up the scrap bowl, then open the latch of the run with my elbow. The flock squawks and gathers around my ankles, ruffling their feathers.

“Wow,” she says. “I’ve never seen chickens this close up—except on my plate.”

“They really like their pecking order,” I tell her. “See that big one? That’s Henrietta. She’s the bossy, popular girl. She makes sure she gets fed first.”

“Huh,” Liberty says. “There’s one of those in every school, too, isn’t there?” She snorts. “So, say, which one would be the school bully?”

I laugh. “Probably Omeletta. Watch out. She’ll go after you.” We probably should have named her Kyle Keefner.

“What about those two?” Liberty points to the newest flock members, two poor puny hens we’ve nicknamed Chick and Fil-A. Chick is missing some feathers—Gramps says she plucks them out herself, from stress. Birds can do that.

“Well,” I say, “they’re at the end of the line. I guess they’re a bit like me and my friend Joon to be honest. Although Joon is moving up in the pecking order.”

Liberty takes the scrap bowl from me, wrinkling her nose at the tangy smell coming off the potato peels and rotten apple rinds. “So he’s moving up, but you’re not?” She nudges the two straggler chickens with her foot. “Seriously. Why even keep track? Pecking orders are for chickens.”

Try telling that to Joon, I think to myself. But I don’t say anything.

On Monday morning, we’ve barely set foot in the building before Principal Coffin calls an all-school pep rally and sports safety presentation.

Ugh. Ugh. Ugh.

I head straight to the main office, down the little hall to my Ready Room.

It’s been a week since I’ve left it. The sketchpad is still there, and I don’t waste time breaking out the markers. I shut the door against the buzz and noise of kids in the hall, heading down to assembly.

Might as well kill time drawing.

Joon and the Trivia Quest are heavy on my mind. This contest is something that should be fun, right? I know a ton of trivia! But I have this feeling, like Joon is throwing it down as an unspoken dare. Do this with him, or else. Prove myself. Or else.

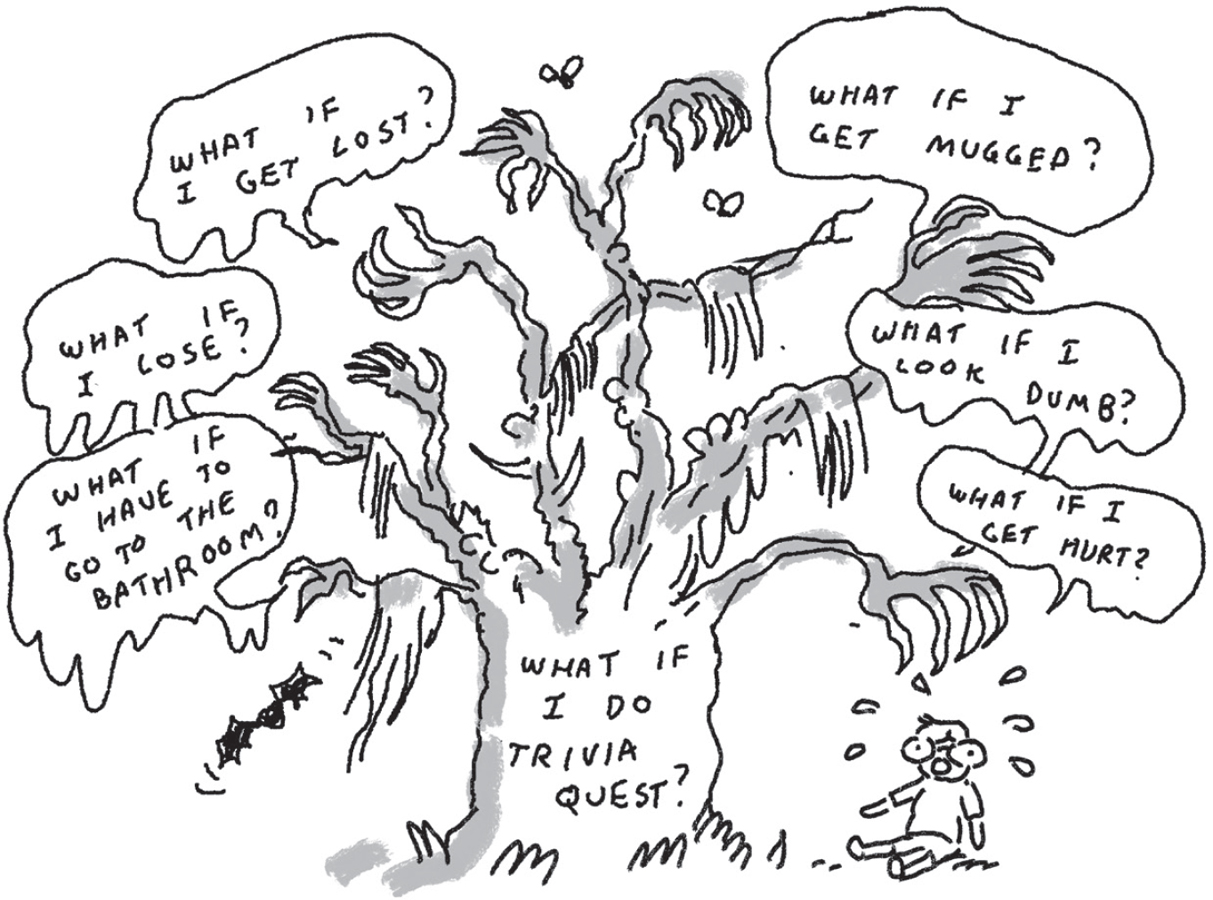

Every time I think of doing the Quest with Joon, worries sprout in me like tree branches. I’m like Groot, the tree creature from Guardians of the Galaxy. I can sprout worry-branches so fast, it’s—worrisome.