“Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau speaking directly to the people of Canada, in the new Liberal Party approach to politics. The prime minister will freely and openly answer all questions.”1

“He’s new. He’s frank.” A shy smile as he talks directly to his interviewer.

“He’s humorous.” To a questioner from the Canadian Club in Kitchener who asked how he felt about creeping socialism: “I’m against creeping socialism, or any other kind of creep.”

“He’s a pragmatist, not bound by doctrine or rigid approaches. He is a seeker after solutions to problems, accepting the challenge of change.” He believes we need to solve the French–English problem, the problem of regional disparity. He believes we need to balance the budget and be fiscally responsible. And he, emphatically, is not making promises, like conventional politicians. Pierre Trudeau is different. The signs behind him in the cheering crowd read: PIERRE FOR THE PEOPLE, COME WORK WITH ME. And finally, lingering on the television screen, there is just his picture.2

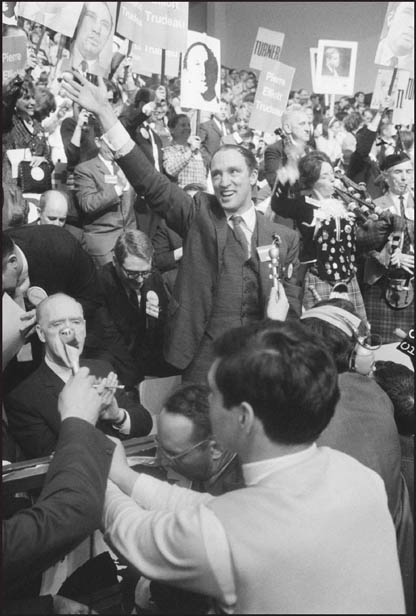

The 1968 campaign was unique in Canadian electoral history in that its main protagonist, Pierre Trudeau, was mobbed like a rock star wherever he travelled. Crowds and television audiences hung on his every word, to the extent that paid advertising was not necessary to get his message out to Canadians. Although some of his more celebrated exploits, like doing a pirouette behind the back of the Queen, were to come later, there were enough during the 1968 campaign to establish Trudeau’s style as a truly different political leader. There were fancy dives into swimming pools, drives in his Mercedes convertible, kisses for pretty girls, signs that this shy intellectual had actually decided to make politics fun. When he visited Rideau Hall to advise the governor general to dissolve Parliament, he slid down the banister. The spirit of the early Trudeau period didn’t last long, but it was fun while it lasted.

Library and Archives Canada. Duncan Cameron, photographer

Pierre Trudeau at 1968 Liberal convention, Ottawa.

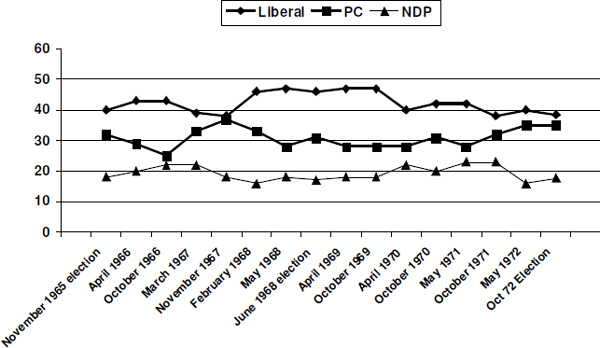

Pierre Trudeau, in victory and defeat, so dominated the era between 1967 and 1983 that it is sometimes difficult to recognize the fact that the developments that changed Canadian politics so thoroughly were only partly a product of Trudeau himself. His victory in the Liberal leadership convention of February 1968 followed an equally dramatic change in the leadership of the Progressive Conservative Party in September of 1967. With new leaders in both major parties, Canadian federal politics entered a new era.

John Diefenbaker’s position as PC leader had been precarious as soon as the party lost power in 1963; it was generally accepted, at least in the academic and journalistic worlds, that a return of a Diefenbaker government was unlikely. Peter C. Newman’s 1963 bestseller was a retrospective entitled Renegade in Power: The Diefenbaker Years, and Peter Regenstrief’s pioneering empirical analysis of voting behaviour in 1965 was called The Diefenbaker Interlude.3 These books and others essentially wrote off the prairie populist as a passing phenomenon, even though he was still the Leader of the Opposition. There were a number of attempts (“coup attempts,” as Diefenbaker no doubt would have described them) to oust him from the party leadership. Quebec member Léon Balcer was convinced that with Diefenbaker at the helm, the party was doomed in Quebec, and he introduced a motion at a National Executive Committee meeting in February 1965 to hold a leadership convention. The motion was only narrowly defeated.4

The surprisingly strong showing of the Conservatives in the 1965 election (see Chapter 5) encouraged Diefenbaker to remain as Conservative leader, but it was not long before various elements in the party, led by national president Dalton Camp, began to manoeuvre to oust him. They felt that Diefenbaker’s autocratic and unpredictable style would not allow the party to be rebuilt in such a way as to legitimately challenge for power again. Supported by the party’s low standing in the polls as 1966 went on (see Figure 6.1), Camp campaigned for a “reassessment” of the leadership and the holding of a leadership convention. Without publicly mentioning the leader by name, Camp argued that the leader must show as much loyalty to the party as the party was expected to show to him.5 At the party’s annual meeting in November of 1966, Camp succeeded in securing re-election as party president, and in establishing the principle that a leadership convention would be held the next year. Diefenbaker loyalists were furious: “It was the night of the knives. It was the date on which the President of the Party assassinated the leader.”6

For many Canadians inside and outside the Progressive Conservative Party, “The Chief” represented the past, while the whole country was looking ahead to the future. The centennial of Confederation was to be celebrated in 1967, and the celebration, symbolized by the new flag (which Diefenbaker strongly opposed), was widely anticipated. Support for the Tories in Quebec and Ontario showed no signs of recovery, and Diefenbaker appeared unconcerned about rebuilding the party in the centre of the country. Rather, he operated more and more in isolation from other Conservatives, and rejected any suggestion that it was time for him to retire. “Regularly, the pundits and prophets have predicted my demise. I allow the pundits and prophets to enjoy themselves while I continue to serve the Canadian people,” he said.7

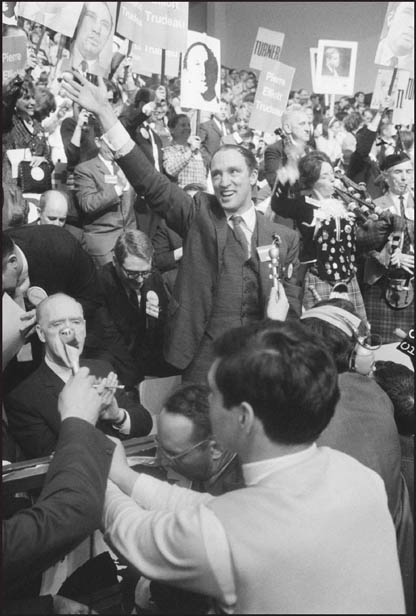

Federal Vote Intention, 1965–1972

The Gallup Report, selected dates

The division in the Conservative Party at this time was extremely bitter. For the pro- and anti-Diefenbaker forces respectively, Dalton Camp became a negative or positive symbol, standing either for the evil forces trying to rid the party of its most successful leader in the twentieth century, or for change and progress. Although he had been unsuccessful in his bid for election in a Toronto riding in 1965, Camp continued to work behind the scenes as a party strategist and national executive member and in public as national president. For his part, Camp was determined to ensure that a strong candidate emerge for the party leadership once the convention was called, because it was quite likely that Diefenbaker himself would enter the contest. His first choice was Nova Scotia Premier Robert Stanfield, a leader he had served in past provincial campaigns as a governmental adviser. But Stanfield procrastinated for such a long time that Camp made plans to run himself, despite the fact that such a move would badly split the party and would likely have been unsuccessful. Another possibility for the succession was Manitoba premier Duff Roblin, who also remained indecisive and undeclared. Both men were wary of their potential inability to unite the party, and fearful of inheriting the leadership of a party so divided as to doom its prospects in the next election.

As it happened, Stanfield did decide to contest the leadership, for the reason, some believe, that he feared the divisive effect on the party if Camp ran for the leadership. Roblin also eventually entered the race, as did a raft of former Tory cabinet ministers: Davie Fulton, George Hees, Wallace McCutcheon, Alvin Hamilton, Donald Fleming, and Michael Starr. Some of these candidates were partisans of Diefenbaker, later to be blindsided by “The Chief’s” last-minute declaration of his own candidacy. With such a crowded field, a long multi-ballot convention became a virtual certainty. Indeed, five ballots were needed before a winner was produced. Roblin was handicapped by the dislike for him harboured by many of the other candidates; his late announcement that he was running had undercut their campaigns. Stanfield was initially handicapped by his association with Camp in his efforts to emerge as a consensus candidate between wings of the party, but he ultimately fared well with the ordinary constituency delegates, who formed the majority of those entitled to vote at the convention.8

Party Leadership Conventions, 1967–1972

Stanfield, who later appeared slow-spoken and bumbling in comparison to Trudeau, was positively quick and snappy in comparison to Diefenbaker, and decisive in comparison to Lester Pearson. He espoused a centrist, cosmopolitan brand of conservatism, which relied little on the populism and rejectionism so vital to Diefenbaker. For example, at the outset of the 1968 election campaign, Stanfield attempted to counter Trudeau’s theme of a “Just Society” with the promise of a guaranteed annual income for Canadians below the poverty line.9 While this proposal was never fleshed out and was ultimately abandoned, it illustrates Stanfield’s willingness to embrace a major social program. Such a stance of governmental activism was also to be found in the 1974 promise to enact wage and price controls to curb inflation. Robert Stanfield indeed appeared to embody the “progressive” side of Progressive Conservatism.

The public initially responded well to Stanfield’s accession to the Tory leadership. As can be seen in Figure 6.1, by the end of 1967 the party had enjoyed a surge of popularity, to the point where they were running in a dead heat with the Liberals. If the Liberals under Pearson were to lose the confidence of the House (they were in a minority situation), it was distinctly possible that the Conservatives could find themselves back in government. The pressure for a renewal of leadership shifted suddenly to the Liberal Party. As Lester Pearson had been hinting that, once the centennial year was over, he would be prepared to leave the leadership, prospective candidates began to ponder their own futures as a potential prime minister.

As with the Conservatives, the list of potential Liberal successors was a long one. But unlike that party, the front-runners were cabinet ministers, not provincial premiers. Paul Martin, who had lost the leadership to Pearson a decade earlier, was confident it was his turn. Finance Minister Mitchell Sharp, Defence Minister Paul Hellyer, Health Minister Allan MacEachen, Registrar General John Turner, and eventually Trade and Commerce Minister Robert Winters, all decided to run for the job. As for Pierre Trudeau, first parliamentary secretary to the prime minister and then justice minister, a number of important figures in the Liberal Party, inside and outside Quebec, were intent on making him prime minister. Pearson himself was committed to the principle of alternation of French- and English-speaking leaders of the party, and wanted at least one strong francophone candidate. When Jean Marchand made it clear he would not run, Trudeau became Marchand’s choice, and eventually Pearson’s choice, as well. Pearson recalls in his Memoirs:

As the campaign progressed, I came to the conclusion that he [Trudeau] and Sharp were the best candidates not only to succeed as Prime Minister but also to win elections. Trudeau created an immediate and exciting impression. He was the man to match the times, the new image for a new era. His non-involvement in politics became his greatest asset, along with his personal appeal, his charisma.10

Intellectual by nature, trained in law and economics, and vitally concerned with politics, Pierre Trudeau might well have set his sights on becoming a university professor, had the Quebec universities been open to adamant opponents of the Duplessis regime. Of the themes that marked his writing, the importance of individual liberty as a guarantee against oppression, and the need for a bill or charter of rights were most prominent.11 A passionate democrat, he was prone to provocative statements, such as: “Historically, French Canadians have not really believed in democracy for themselves; and English Canadians have not really wanted it for others.”12 A fervent anti-nationalist, his diatribe against “Separatist Counter-Revolutionaries” begins, “I get fed up when I hear our nationalist brood calling itself revolutionary.”13 Though not explicitly a socialist, his writings were sympathetic to socialists, whom he urged to embrace federalism rather than centralism on the grounds that it provides numerous arenas for reform. In the periodical Cité Libre, which Trudeau founded with his friend Gérard Pelletier, he wrote political commentary and criticism on many subjects from 1950 onward. In 1956, a long and thoughtful analysis of the social, religious, economic, and political nature of Quebec society produced by Trudeau as the introduction to a book detailing the strike at Asbestos made his name more prominent as a commentator and analyst.14

By the mid 1960s, Trudeau had joined the Liberal Party, a party which had not escaped his critical pen and tongue. His view in 1960, for example, of the preceding Liberal dynasty was that: “Personally, I was convinced that King and St. Laurent had stayed too long in office and turned the Liberals into a party both arrogant and not democratic enough.”15 But his hopes that Diefenbaker would make substantive changes through, for example, introducing a meaningful Bill of Rights instead of one that cited good intentions but had no primacy as legislation, or outlawing the death penalty, were soon dashed. Trudeau’s opinion of Lester Pearson’s decision in the 1963 election campaign to accept nuclear warheads for missiles stationed in Canada was that: “Power beckoned to Mr. Pearson. He had nothing to lose but honour. He lost it. And his whole party lost it too.”16

Library and Archives Canada.

Robert Stanfield speaking at a dinner, Vancouver, 1971.

Despite these views, Trudeau was intellectually attracted to liberalism, and practically, he was attracted to power. The opportunity that beckoned in 1965 to him, Gérard Pelletier, and Jean Marchand, together with other Quebec colleagues like Marc Lalonde, to help fashion the Liberal Party’s constitutional policies toward Quebec and toward individual rights, might never reappear. Trudeau justified his decision thusly: “Once the political critic decides to take action, he will inevitably join a political party he has already opposed,” and, although it is fair for others to point this out, it is inevitable that compromises are made and important that action be taken.17

Once Trudeau was elected to Parliament in 1965, events moved quickly. He was appointed first parliamentary secretary to the prime minister, and then minister of justice. And then, in 1968, he sought the leadership of the party. Trudeau felt himself swept up in a tide not of his own making: “Running for the leadership seemed presumptuous for someone like me who had no deep roots in the Liberal Party, who barely knew the main party activists, and whose accomplishments to date were modest at best.”18 Some of Trudeau’s biographers, like Richard Gwyn, take Trudeau’s ostensible reluctance to seek the leadership at face value, though Gwyn also notes that he kept up the pretense of indecision even after he had decided.19 It is true, though, that Trudeau’s newness to the Liberal Party meant that he could not count on support from many longtime party activists.20 He had to sell himself by virtue of his appeal to the public, which did not perceive him as a likely leadership candidate prior to the end of 1967,21 and his possession of the aura of a likely election winner, which was rapidly given to him in the media.

Trudeau’s candidacy for the Liberal leadership was helped along by his performance at a series of events that brought him more and more into the public eye. As minister of justice, he introduced, and eloquently defended, a bill that modernized legislation on divorce, abortion, and homosexuality, and in doing so uttering the memorable phrase, “the State has no business in the bedrooms of the nation.” Trudeau biographers Stephen Clarkson and Christina McCall say that, while this phrase was not original with Trudeau, “Delivered by a minister of the Crown wearing a leather coat and sporting a Caesar haircut, it had an electrifying effect on the public imagination.”22

In early 1968, Trudeau was the “star” of a federal–provincial First Ministers’ meeting on the Constitution. During the televised proceedings, Trudeau entered into a confrontation with Quebec Premier Daniel Johnson over the place of Quebec in a federal Canada. Trudeau’s defence of federalism at a time when separatist threats were looming, not only in Johnson’s position but with the conversion of Quebec Liberal stalwart René Lévesque to the separatist cause, galvanized opinion in his favour, particularly in English Canada. Here was an attractive, highly intelligent federalist francophone who could “put Quebec in its place,” or at least “deal with Quebec.” That he based his opposition to Quebec nationalism on the position that Quebec should have a larger arena to operate in, as opposed to the narrow vision of the separatists, was a bonus.

“I tried to express simple and widely understandable ideas,” wrote Trudeau later, “because I knew that if I became the leader those ideas would be the party platform in the general election that would follow. And so I based my campaign on the central theme of the Just Society.”23 Whatever the origins of the phrase “Just Society,”24 Trudeau made it his own in 1968, in both his leadership campaign and the ensuing election. It was a brilliant organizing device, pointing as it did toward the future and committing the Liberal Party to leaving old prejudices and practices behind. It had relevance in all the issue areas that Trudeau wished to address. In reference to the liberalization of the Criminal Code and in moral areas like homosexuality, it promised justice under the law to all groups. In reference to national unity, it promised to “redress the Canadian state’s traditional injustice towards French.”25 In reference to social welfare, it promised to support those in society who were in need. And in the economic realm, it called for attention to the development of poor regions like Atlantic Canada. In that one phrase of the “Just Society,” Trudeau had established his mastery of all three essential issue areas for electoral success in Canada.

But the fine words would not have had the same effect if delivered by another speaker. It was Trudeau’s personal charisma that put the message across. His style was full of seeming contradictions, shy yet forthright, playful yet serious, self-effacing yet arrogant, caring yet intolerant, serene yet impatient, tough yet vulnerable. His appeal to women was extraordinary, but female reaction to him did not appear to alienate males. Rather, Trudeaumania was a phenomenon which struck young and old, male and female. Pierre Trudeau seemed modern — the embodiment of the spirit of the country’s second century. When Trudeau announced his candidacy for the Liberal leadership, he quickly became the odds-on favourite to win, despite the crowded field of candidates.

Aside from Pearson’s covert approval, Trudeau had little establishment support before the convention itself. In part, this was because there were many ambitious ministerial candidates who had arranged for support bases within the caucus and party apparatus. In addition, there was a certain amount of resentment at the fact that Trudeau seemed to have come from nowhere to front-runner without paying his dues and earning the right to this status. One outspoken cabinet member, Judy LaMarsh, made no secret that she considered Trudeau an “arrogant bastard,” even though she grudgingly admired many of his accomplishments as justice minister.26

A decisive development in the leadership race occurred when Mitchell Sharp withdrew from the race shortly before the convention and supported Trudeau, based on his self-assessment that he did not have a strong chance of winning. This was a sign of establishment approval that the finance minister would support the newcomer.27 With Sharp came his parliamentary secretary, Jean Chrétien. At the convention, as the ballots went on, the contest became one between Trudeau and Robert Winters, a quintessential establishment candidate. This represented a left–right split within the party, as the old guard lined up behind Winters, except for John Turner, who refused to withdraw from the final ballot and thus maintained his neutrality. After four ballots, the verdict was narrowly in Trudeau’s favour. The young people in the crowd were ecstatic. The Trudeau Era in Canadian politics had begun.

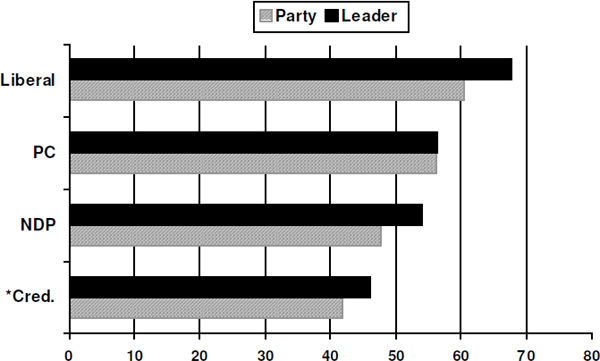

It is difficult in current political times to appreciate the atmosphere of hope and joy that surrounded the 1968 election campaign. “In a campaign that often seemed like a joyous coronation, crowds gathered by the tens of thousands . . . simply to see [Trudeau]. Wherever he went, he was mobbed like a pop star.”28 It was remarked by many observers that Trudeau’s speeches were often dull and boring, but this did not seem to matter; the crowds cheered them anyway. Trudeau’s popularity was rated in the National Election Study 100-point thermometer scale measurement at 68, the highest score recorded for a Canadian political leader in these surveys before or since (see Figure 6.2). What is less often noted is that the thermometer ratings for the leaders of the two other major parties were also in positive territory, Stanfield at 56 and Douglas at 54. The 1968 election was conducted in a spirit of public benevolence and relative lack of animosity. It really did appear to be a “new politics.”

“In the spring of 1968,” wrote Ed Broadbent, later to lead the NDP, “we were prepared to vote for what we wanted to be rather than what we ought to be.”29

If the Liberals initially proclaimed that, in a spirit of pragmatic realism, they were not going to make election promises, the other parties were not similarly inhibited. Realizing that they could not compete on the basis of leader personality, the Conservatives began issuing policy statements early in the campaign, and continued for the duration. First, in early May, came the dramatic announcement that the Tories would bring in a guaranteed annual income for those living in poverty and unable to earn a living.30 This was an effort designed to blunt the appeal of Trudeau’s “Just Society,” by allowing the Tories to claim they were actually going to do something to achieve equality. At the end of May, Conservative candidates received a blue leather-bound policy platform detailing 56 election proposals the party leadership was prepared to make. Many of these were early proposals of the party’s policy advisory committee, headed by President Tom Symons of Trent University.

Party and Leader Thermometer Scale Ratings, 1968

1968 Canadian Election Study. N=2767. * Créditiste asked in Quebec only (N=685).

This document outlined a series of innovations in many areas besides that of social welfare. It focused on the state of Aboriginal life, and proposed to reorganize the Indian Affairs Department via a special task force. It promised to set up a special commission to control environmental pollution and develop a “national pollution abatement code.” It proposed a complete foreign policy review, including the country’s roles in NATO and NORAD. And in the agriculture area, improvements were promised in the creation of port facilities, farm credit, and crop insurance, with a special plan for development of eastern agriculture.31 Added to these ideas was a promise by Stanfield in mid-June that, if the Tories formed a government, homeowners would be able to deduct mortgage interest over 7 percent from their income taxes.32

Not wanting to be outdone, the Liberals soon countered with a red leather-bound policy book containing their own platform. “The document is a dramatic attempt by the Liberals to counteract the image of Trudeau as the hero of a screaming cult of teenagers and to portray him instead as a Prime Minister with a carefully thought out program for his country,” wrote Peter C. Newman.33 The Liberal policy book, though vaguely worded and featuring few ideas with specific pricetags attached, did raise a number of issues that were to emerge at various times during Trudeau’s tenure in office, such as an increase in federal government bilingualism, a charter of rights to be placed in the Constitution, a task force on the cities, and a reorganization of government departments.

The NDP ran an issue-based campaign, which began with a promise to raise the old-age pension. In addition, it took advantage of two prominent reports to propose implementing their recommendations. One was the Carter Report, a Royal Commission on taxation, which proposed the implementation of a capital gains tax, among other reforms. The second was the Watkins Report on Canadian ownership of the economy, which proposed curbs on foreign ownership. NDP leader Tommy Douglas declared himself willing to accept the recommendations of both of these commissions in the interest of implementing genuine fairness throughout society.34 However, the NDP’s attempt to put a socialist class-based interpretation on Trudeau’s call for a “Just Society” was lost in the wave of support for the Liberal leader.

Most Important Issues in the 1968 Election

Percent citing issue as “extremely” or “very” important.

1968 Canadian Election Study. N=2767.

On paper, the number of issues in the electoral marketplace in 1968, and the detail with which they were delineated, was at least the equal of other Canadian elections. The importance of these issues, at least in their specific forms, is more problematic. Figure 6.3 gives the public rating from the National Election Study of the most important issues in the election. Taking them at their face value, we can see that several economic issues, particularly the “cost of living” and “unemployment,” were cited as extremely or very important, along with “housing,” which also has an important economic dimension. A variety of other issues, like those dealing with health and welfare and “how to treat Quebec” appeared less important to people. As we have already stressed, however, these latter subjects were very much a part of the Trudeau appeal, as encapsulated in his advocacy of the Just Society.

On the issue of Quebec, Trudeau proposed the extension of bilingualism, but explicitly rejected any special treatment for the province — a stance reminiscent of John Diefenbaker’s “One Canada” position. The Liberal leader distinguished himself overtly from the approach recommended by the other two major parties. The NDP was in favour of special status for Quebec, a position, never clearly spelled out, which coexisted uneasily with the party’s traditional commitment to a strong central government. The Progressive Conservatives, weakened substantially in the province after the dissolution of the Diefenbaker majority in the early 1960s, adopted a “two nations” policy toward Quebec at a policy convention in 1967. The party had intended this to be a simple and noncontroversial recognition of the existence of “two founding peoples” in Canada, in an effort to win back Quebec support. Through translating this idea from English to French and back again, the slogan of “two nations” took on the potential connotation of support for a Quebec state to match the separate nation.

The notion that the Tories were “soft on Quebec” was reinforced by the party’s decision to appoint Marcel Faribault, a prominent adviser to Quebec Premier Daniel Johnson, as Quebec lieutenant for Stanfield.35 Since one of the events that had led to Trudeau’s rise to prominence was a widely publicized attack on Johnson for the Union Nationale’s quasi-indépendentiste stance in constitutional affairs, the gauntlet was thrown down, and it was only a matter of time before Trudeau and the Liberals picked it up. In early June, Trudeau delivered a speech in British Columbia ridiculing the Conservatives for having “two voices on Quebec” — Faribault, and former justice minister Davie Fulton, who had claimed that Faribault did not speak for the party.36 Then, as the campaign reached its conclusion, the Liberals published newspaper ads in the West attacking the Conservatives for supporting “two nations,” implying that they were willing to break up the country. An indignant Stanfield accused Trudeau of a “smear campaign,” while the latter replied that “he would have the ads withdrawn if Stanfield would state all over the country, including in Quebec, that he is opposed to the two nations concept.”37

The Liberal exploitation of Trudeau’s willingness to confront nationalist forces in Quebec came to a head on the day before the election. By coincidence or by design, the election date was set for June 25, one day after Quebec’s St-Jean-Baptiste Day celebration. Trudeau had accepted an invitation to take part in a viewing of the traditional parade in Montreal from a reviewing stand downtown. At the parade, there was a violent clash between police and separatists, when the demonstrators attacked Trudeau with thrown bottles and other objects. Although urged to leave for his own safety, Trudeau remained firmly planted on the stand, clearly visible to the crowd, and the photographers. Conservative Party national president (and losing Toronto-area candidate) Dalton Camp was quoted as saying about the St-Jean-Baptiste Day riot, “The separatists made a supreme contribution to the achievement of our majority Government. When you are lucky in politics, even your enemies oblige you.”38 The election day headline in the Toronto Star was “Trudeau Defies Separatists.”39

Camp’s ironic reference to majority government echoes one of the Liberal themes of the campaign. After three elections in a row (1962, 1963, and 1965) that produced minorities of seats for the leading party in the House of Commons, there was a widespread feeling in the country that a majority was desirable this time to enable the government to be solidly in place for a normal term of office. Figure 6.3 shows that two-thirds of respondents to the National Election Study thought the issue of majority government was either “extremely” or “very” important. The tenor of the Liberal campaign, in particular, was designed to appeal to those wanting a stable majority. In his appearances, Trudeau continually urged Canadians to participate, to exchange ideas, to join him to work together for a great future. The implication was that he could be trusted to provide an environment for the carrying out of a great national leap forward to a better, more prosperous, more equal, more just society. All the talk of unity and togetherness may have masked the inevitable regional-, class-, and group-based conflicts in society, but it was extremely popular in the short run.

Trudeaumania appears to have overtaken the original strategic plans for the Liberal election campaign. A two-stage plan had been devised whereby, after the initial burst of enthusiasm for Trudeau had been satisfied by a whirlwind cross-country tour to let people see the leader and bask in his presence, he would become more serious and “prime ministerial” and produce more substance. This second stage was submerged by the waves of enthusiasm for Trudeau, which, to the astonishment of party officials, did not abate throughout the course of the campaign. “An examination of the party files suggests that Liberal strategists hardly understood Trudeaumania — let alone created it.”40 In part, this was because the wildest part of the passion for Trudeau was carried forward by young people, often those too young to vote.

The outpouring of enthusiasm for Pierre Trudeau overwhelmed Liberal organizers, and led to the establishment of a special youth wing of the Liberal campaign, called Action-Trudeau. Although there were four national coordinators, the structure called for the setting up of a separate Action-Trudeau group in each constituency, with a leader appointed by the campaign chairman.41 The local leader recruited and trained the young workers in canvassing and phoning voters, and organized demonstrations and local entertainment. The national coordinators, and 10 provincial coordinators who worked under them, designed and supplied masses of promotional material, such as buttons, posters, and patterns for Trudeau mini-dresses and other clothing items. The existence of this separate campaign organization led by young people created substantial hostility on the part of the regular riding organizations, feelings which were only partly alleviated by the realization on their part that they could not handle the outpouring of young “Trudeau-workers.”

Whatever their reservations, party officials had no wish to dampen the spirits of the wave of new supporters they had acquired. There is evidence, however, that as the campaign wore on, “Liberal strategists . . . started to get defensive and apprehensive about this new electoral phenomenon. Television was giving their leader all the exposure they felt they needed with regular news coverage, so the party decided not to purchase any television advertising.”42 When utilizing the slots of free broadcast time allocated to them, the Liberals ran long segments from Trudeau’s speeches. Ironically, given his charismatic appeal, Trudeau was not a dynamic speaker, particularly when he stuck to a written text, as he often did.

In one free-time telecast, a half-hour was selected from a speech to a large outdoor crowd in Hamilton’s Civic Stadium, normally used for football games. As usual, Trudeau’s theme was the Just Society, but the subtopics were generalities: the importance of labour and management working together; the importance of the individual; the need to maintain social security; protection for consumers; the goal of a prosperous economy; the ideal of a peaceful world. He called on “all Canadians” to join him to solve these problems, and spoke of how “the Liberal Party is our party.”43 Over and over, these apparent platitudes were interrupted by applause. Cool in person, and cool on television, Trudeau exemplified the qualities of leadership. His friend Marshall McLuhan thought he was a perfect fit for the new electronic age.44

Not only was television campaign coverage important in 1968 to an unprecedented extent, but an event was staged which would later become a fixture in subsequent Canadian election campaigns — the leaders’ debate. Held on June 9, two weeks before election day, the “National Debate” consisted of Pierre Trudeau, Robert Stanfield, and Tommy Douglas answering questions posed by a panel of journalists (Réal Caouette of the Créditistes joined the program for the last 40 minutes). Eighteen questions were posed during the two-hour program, with each of the three major party leaders having a limited time to answer each one.45 Thus, the format was not so much a “debate” directly between the leaders as it was an extended “question and answer” session, where the leaders all addressed the same subjects. The topics ranged widely. The first question, stimulated no doubt by the recent assassination of Robert Kennedy in the United States, was about mandatory fingerprinting for those purchasing weapons. This was followed by a series of questions about the economic situation, including taxes, and later on by questions regarding the place of Quebec in Confederation, foreign policy, and other topics.

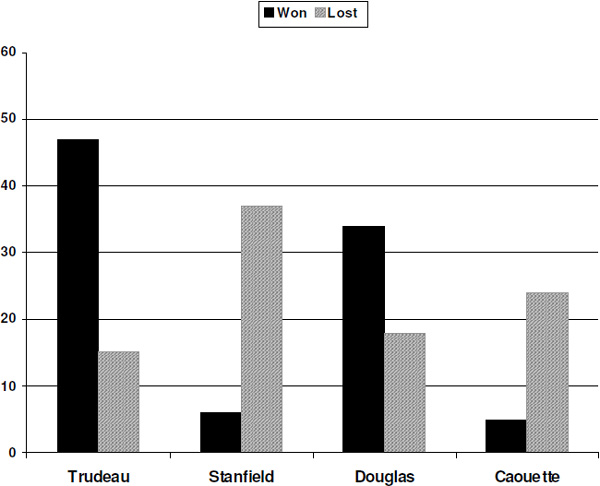

Both at the time, and subsequently, the verdict has been negative regarding the impact of the debate. The day after, the Toronto Star headlined “PM Admits It: Great Debate ‘Pretty Dull’ Stuff,” and Peter Newman opined, “Nobody won it — but the audience lost.”46 In his history of the Liberal Party, Joseph Wearing calls the debate “a disappointing bore.”47 But was there a winner? Two days later, Peter Regenstreif reported that a national survey had shown that NDP leader Tommy Douglas was chosen by 40 percent of viewers as having made “the best impression on you,” with Trudeau second at 27 percent. A further question had established, however, that only 5 percent claimed that the debate had changed their vote intention.48 Figure 6.4 shows the answers of the National Election Study sample to the questions of the winners and losers in the debate. The results are somewhat different from those reported at the time. In this survey done after the election, Trudeau clearly emerges as the one “who gained most in your eyes as a result of the debate,” with Douglas in second place. It is clear, however, that Robert Stanfield suffered from his appearance in this television event. He appeared to be fumbling for answers at several points, and to be at a loss for words in determining his positions on some issues. Tommy Douglas was sure of himself and his answers, but sounded rather like the preacher he had once been. Suddenly joining the group near the end of the debate, Réal Caouette was at odds with all the others in terms of style, waving his hands, speaking quickly and passionately. And Trudeau was calm and almost above the fray, calling once again for the people to join him in searching for Canada’s great future.

Perceived “Winners” and “Losers” in the 1968 Leaders Debate*

1968 Canadian Election Study. N=2767.

WON – “Who gained most in your eyes as a result of the debate?”

LOST – “Which did you like the least?”

For all the assumptions that the election was over before it began, because Trudeaumania would sweep the country, the Liberal victory was modest in scope (see Table 6.2). The party’s popular vote rose by about 5 percent nationwide, and the Conservative vote declined by only 1 percent. However, this shift in the popular vote produced 24 additional seats and a comfortable majority for the Liberals, whereas the Conservatives lost an equivalent number of seats. The Atlantic region went solidly for Stanfield, but the rest of the country was a different story. The Liberals held steady in Quebec and picked up seats in Ontario and the West to produce the result. The NDP won an additional seat, for a total of 22, but Tommy Douglas lost his riding by a handful of votes and shortly afterward announced his retirement as leader, a bitter reward for his success in the leadership debate. The Créditistes elected 14 members from ridings in rural Quebec, a minor success for leader Réal Caouette. Figure 6.5 shows that the electoral turnover was solidly in the Liberal direction, with twice as many voters moving from the PCs in 1965 to the Liberals in 1968 as moving from the Liberals to the PCs. In addition, those moving into the electorate in 1968, either from abstention or ineligibility, were more than twice as likely to choose the Liberals as any other party.

The post-election situation showed a decided “honeymoon effect” for Pierre Trudeau. Party identification (see Figure 6.6) measured after the election found that twice as many people considered themselves Liberals as Conservatives, a greater margin than the breakdown of votes for the two parties in the election. Having made so few specific promises during the election campaign, but promised so much in a general sense, expectations were bound to be sky high. Participatory democracy, social welfare, a new deal for cities, and above all a Just Society would be the heritage of the new era.

Results of the 1968 Election

Electoral Turnover, 1965–1968

1968 Canadian Election Study. N = 2439.

As Trudeau set about governing, he placed his leadership rivals in the cabinet, but few experienced party operatives in positions of organizational power.49 The unusual nature of the 1968 election campaign, where all the attention was focused on one leader and where the party itself seemed irrelevant, where the contact was directly between the leader and his adoring public, left Trudeau ill-prepared for the time-consuming and tedious work of implementing many of his “big ideas.”

During the 1968 to 1972 period, several factors led to a growing sense among Canadians that Pierre Trudeau was not the man they thought they had elected in 1968. The first problem was the seeming decline in the authority of cabinet, Parliament, and the Liberal Party itself as Trudeau surrounded himself with a new and powerful set of political advisers. Two figures in particular led the list. First as deputy clerk of the Privy Council and then as clerk, Michael Pitfield wielded extensive power over the bureaucracy. Only 32 years of age when given the clerk’s office in 1970, his influence was based on his closeness to Trudeau. Pitfield was the architect of numerous organizational changes to the federal public service between 1968 and 1972, which included new ministries of state such as Urban Affairs and Science and Technology. He was also criticized for his politicization of the public service and some Ottawa commentators were convinced that the top ranks of the civil service had become indistinguishable from the Liberal Party.50

Marc Lalonde, a Montreal lawyer and member of Trudeau’s original support group, was made head of the Prime Minister’s Office; as the chief of staff, he dispatched orders to bureaucrats and cabinet ministers. In isolating Trudeau from the public, Parliament, and the party between 1968 and 1972, Lalonde came to illustrate the perception that Trudeau’s personal staff had more influence with him than the cabinet. Indeed, according to biographer Richard Gwyn, “almost all Trudeau’s ministers were intimidated by him and tailored their arguments to suit his style.”51 As if mesmerized by the fact that his personal appeal as leader had propelled his government to power, Trudeau allowed that personality to supersede both his cabinet and his party. In fact, some political commentators at the time claimed that he had, for all intents and purposes, replaced the Westminster-style parliamentary system with a quasi-presidential one. In most ways, the Liberal Party ceased to function between 1968 and 1972. Trudeau never consulted party president John Nicol, and the traditional intelligence-gathering function of the party and of backbench MPs was usurped by the new regional desks in his own office.

It was not long before things started to go wrong for the new government. Despite some initial indications from the provincial premiers that they would consider constitutional change, many of them began to grow suspicious or disinterested in entertaining proposals from Mr. Trudeau. For the first three years, federal–provincial negotiations on these matters had made little progress. In June of 1971, however, there appeared to be a breakthrough at the federal–provincial First Ministers’ Conference in Victoria. After three days, Trudeau and the premiers emerged with an agreement that included a formula for amending the Constitution, a modest charter that guaranteed some rights, and language that would entrench the Supreme Court as well as ensure that any future judicial appointments would receive mandatory provincial approval. At last, Trudeau’s obsession with constitutional renewal seemed to have been achieved. Within days, however, Robert Bourassa, the newly elected Liberal premier of Quebec, was subjected to a backlash of Quebec nationalists and trade unionists who were highly critical of the Victoria agreement. Soon he withdrew his consent to the deal and Trudeau was back at square one. There is little question that the energy he had put into the constitutional renewal project had been done at a cost to other planks in the domestic agenda. As Stephen Clarkson and Christina McCall concluded, “The public was tired of the subject. Canada’s economic troubles were becoming serious, and arcane arguments over linguistic rights and amending formulas seemed irrelevant. Even Trudeau’s closest allies in the constitutional wars thought the issue was dead.”52

Federal Party Identification in 1968

1968 Canadian Election Study. N=2706.

The most critical event in the national unity area that occurred during the Trudeau years, one that polarized the public more than any other, was the October Crisis of 1970. A small, revolutionary group promoting Quebec independence kidnapped Quebec’s minister of labour, Pierre Laporte, on October 10, 1970, five days after they had seized James Cross, the British trade commissioner. Quebec nationalism, always Trudeau’s bugbear, seemed to have taken a seriously violent turn. Trudeau was advised by his key political confidants that the only solution was to invoke the War Measures Act, a piece of legislation designed for wartime, when normal civil rights and legal procedures were suspended. The cabinet unanimously agreed to invoking the act on October 15, and it came into force the following morning.

Under this legislation, political rallies were banned and membership in the Front de Libération du Québec (FLQ) was made illegal, the legal right of Habeas corpus was suspended, and police were allowed to arrest, interrogate, and detain suspects without charge for up to ninety days. Many people were detained, particularly after Laporte’s body was found. By early December 1970, the crisis was all but over but there was a great deal of political fallout. On one hand, Trudeau’s “toughness” was admired in much of English Canada. On the other, the self-described champion of civil rights and liberties had imposed the War Measures Act, which suspended those very rights. Whether or not this was the right decision at the time has been debated for years. There is no doubt, however, that it emphasized the authoritarian side of Trudeau’s “paradoxical” nature.53

While the idea that Trudeau would be the agent of Canadian national unity died a sudden death with the October Crisis of 1970, the decline of public confidence in his stewardship of the economy was more gradual. Expansion of the Canadian economy in the early and mid 1960s, though it had lowered the unemployment rate, produced an increase in inflation. By 1968, the inflation rate had reached 4.1 percent (after being, for example, 2.4 percent in 1965 and 1.8 percent in 1964) and rose to 4.5 percent in 1969.54 This situation produced a substantial rise in public concern about inflation; in 1970 respondents to the Gallup poll reported it as the most important problem facing the country. The Bank of Canada reacted to the increase in inflation by curtailing the growth of the money supply, a policy that temporarily lowered the inflation rate but sharply increased unemployment.55 Worried about the upcoming election, the government reintroduced an expansionary monetary policy that did almost nothing to the unemployment rate, but fuelled inflation once again. By the time of the 1972 election, the inflation rate was as high as it had been in 1969, and public concern about it had reached new heights.

The dramatic 1968 election victory set the stage for the Trudeau dynasty, the fourth in Canadian political history and the third to be organized by the Liberal Party. It became the most personalized Canadian dynasty, even allowing for the immense national appeal of Macdonald and Laurier. Unlikely as it seemed to those who knew him before he entered politics, Pierre Elliott Trudeau struck a responsive chord with much of the Canadian electorate. The Trudeau appeal was partly based on his ideas, especially individualism, with an emphasis on rights and accompanied with a splash of Canadian nationalism. It was also intimately tied up with the way these ideas were expressed; no previous leader had possessed the apparently effortless ability to give listeners a vision of the intellectual depth that lay beneath the words. Although close to 50 and just a little younger than his major opponent, many people referred to Trudeau as “young.”56 In relation to his two predecessors in office, of course, he was young. But it was primarily the dynamism and vigour with which he conducted himself that produced the image of youth.

The relatively contentless character of the 1968 election raised expectations very high for the Trudeau government. When these were not immediately fulfilled, and when the economic and national unity crises followed so shortly upon the election victory, the result was diminished popularity for the Liberals (see Figure 6.1). But despite the electoral setbacks of 1972 and 1979, Trudeau headed a Liberal government for all but nine months of the period between June 1968 and September 1984. Though the negative aspects of his image — the aloofness, arrogance, and authoritarianism — had come to the fore by the end of his career, the forcefulness of his personality was such that, as his biographers put it, “He haunts us still.”57

1. Liberal Party of Canada, free time broadcast, 5/31/1968. PAC V1 8805-0031.

2. Liberal Party of Canada, free time broadcast, 6/8/1968. PAC V1 8805-0015.

3. Peter C. Newman, Renegade in Power: the Diefenbaker Years (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1963), and Peter Regenstrief, The Diefenbaker Interlude (Toronto: Longman’s, 1965).

4. These are described in detail in George C. Perlin, The Tory Syndrome: Leadership Politics in the Progressive Conservative Party (Montreal, McGill Queen’s Press, 1980), Chapter 4. For other accounts, see James Johnston, The Party’s Over (Toronto: Longmans, 1971), 18; Geoffrey Stevens, Stanfield (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1973), 162.

5. Camp delivered a speech to the Albany Club, a private gathering of influential Conservatives, in May of 1966, in which he argued, “the party is not the embodiment of the leader but rather the other way around; the leader is transient, the party permanent.” Geoffrey Stevens, The Player: The Life and Times of Dalton Camp (Toronto: Key Porter, 2003), 168. This influential speech was never published.

6. Robert Coates, The Night of the Knives (Fredericton: Brunswick Press, 1969), 46. This book is full of inside accounts of the activity of the “Camp storm troopers” (57) as they accomplished their bloody deed.

7. John G. Diefenbaker, One Canada: The Tumultuous Years, 1962 to 1967 (Toronto: Macmillan, 1977), 264.

8. On Roblin, see Perlin, op. cit., 102–03. For an account of the convention, see Joseph Wearing, Strained Relations: Canadian Parties and Voters (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1988), 208. Other substantial groups of delegates were party parliamentarians, and “delegates at large” from constituent groups within the party.

9. Jack Cahill, “Stanfield Promises Guaranteed Income for Nation’s Poor,” Toronto Star, May 6, 1968: 1.

10. Lester B. Pearson, Mike, Vol. 3 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1975), 325.

11. Jacques Hebert, prefatory note to Pierre Elliott Trudeau, Approaches to Politics (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1970).

12. This is the first sentence of Trudeau’s essay “Some Obstacles to Democracy in Quebec,” originally published in the Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science in 1958 and reprinted in Pierre Elliott Trudeau, Federalism and the French Canadians (Toronto: Macmillan, 1968), 103.

13. Ibid., 204. Originally published in Cite Libre in 1964.

14. Pierre Elliott Trudeau and others, The Asbestos Strike (Toronto: James Lewis and Samuel, 1974), originally published as La Greve de l’amiante in 1956.

15. Pierre Elliott Trudeau, Against the Current: Selected Writings, 1939–1996.

16. Trudeau in Cite Libre, quoted by Stephen Clarkson and Christina McCall, Trudeau and Our Times, Vol. 1 (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1990), 90.

17. Pierre Elliott Trudeau, Cite Libre, October 1965, in Against the Current, op. cit., 25.

18. Pierre Elliott Trudeau, Memoirs (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1993), 85.

19. Richard Gwyn, The Northern Magus (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1980), 66.

20. Michel Vastel, The Outsider: The Life of Pierre Elliott Trudeau (Toronto: Macmillan, 1990), 129.

21. As late as December of 1967, The Gallup Report was not including Trudeau as a major contender for the Liberal leadership in its polls of public opinion on the matter, and the public was not raising him as a possibility either. Only 3 percent in that month mentioned any other contender than Paul Martin, Mitchell Sharp, Paul Hellyer, and John Turner.

22. Stephen Clarkson and Christina McCall, Trudeau and Our Times, Vol. 1 (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1990), 107.

23. Trudeau, op. cit., 85.

24. Clarkson and McCall say “it was a label Trudeau had appropriated from Frank Scott.” Op. cit., 115.

25. Trudeau, op. cit., 85.

26. Judy LaMarsh, Memoirs of a Bird in a Gilded Cage (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1969), 336–45.

27. Mitchell Sharp, Which Reminds Me . . . A Memoir (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1994), 162.

28. George Radwanski, Trudeau (Toronto: Macmillan, 1978), 106.

29. Ed Broadbent, The Liberal Rip-Off: Trudeauism vs the Politics of Equality (Toronto: New Press, 1970), 3. As the title indicates, Broadbent argues that the 1968 confidence in the Trudeau Liberals was misplaced.

30. Jack Cahill, “Stanfield Promises Guaranteed Income for Nation’s Poor,” Toronto Star, May 6, 1968: 1.

31. Jack Cahill, “Tories Make 56 Promises . . . And Its Only the Beginning,” Toronto Star, May 31, 1968: 1,4.

32. Robert Miller, “Stanfield Promises Tax Relief to Ease High Mortgage Cost,” Toronto Star, June 18, 1968: 1.

33. Peter Newman, “Now Non-Promising Trudeau Has 80 Promises to Make,” Toronto Star, May 31, 1968: 1, 21.

34. Alan Whitehorn, Canadian Socialism (Toronto: Oxford, 1992), 88–89.

35. Andrew Salwyn, “Top Johnston Aide to Lead Quebec Tories,” Toronto Star, May 13, 1968: 1.

36. Frank Jones, “Trudeau Hits Tories’ Two Voices on Quebec,” Toronto Star, June 4, 1968: 1.

37. Robert Miller, “Liberals Try to Exploit Anti-Quebec Feeling,” and Frank Jones, “Trudeau Repudiates Ads Saying Tories Want Two Nations,” Toronto Star, June 20, 1968: 1.

38. Camp quoted in Donald Peacock, Journey to Power: The Story of a Canadian Election (Toronto: Ryerson, 1968), 377.

39. Toronto Star, June 25, 1968: 1.

40. Joseph Wearing, The L-shaped Party: The Liberal Party of Canada, 1958–1980 (Scarborough, ON: McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 1981), 190.

41. Jon H. Pammett, “Personal Identity and Political Activity: The Action-Trudeau Campaign of 1968,” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Michigan, 1971. The account of Action-Trudeau in this paragraph is drawn from this study. A portion of this study, which does not concentrate on the political operations of Action-Trudeau, can be found in Jon H. Pammett, “Adolescent Political Activity as a Learning Experience: The Action-Trudeau Campaign of 1968,” in Jon H. Pammett and Michael S. Whittington, eds., Foundations of Political Culture: Political Socialization in Canada (Toronto: Macmillan, 1976), 160–94.

42. Wearing, op. cit., 190–91.

43. Liberal Party of Canada, free-time broadcast, 6/12/68, PAC V1 8805-0025.

44. Clarkson and McCall, op. cit., 112, 126.

45. PAC V1 8210-0033/4.

46. Toronto Star, June 10, 1968: 1.

47. Wearing, op. cit., 191.

48. Toronto Star, June 12, 1968: 1.

49. Christina McCall-Newman, Grits: An Intimate Portrait of the Liberal Party (Toronto: Macmillan, 1982), 120–28. See also Keith Davey, The Rainmaker: A Passion for Politics (Toronto: Stoddart, 1996), 159–63.

50. Gwyn, op. cit.,78. Some Liberals who were awarded high-ranking civil service jobs were: ex-minister Bryce Mackasey, who was named Chairman of Air Canada; Bill Teron at the Central Mortgage and Housing Corporation; and Pierre Juneau at the National Capital Commission.

51. Ibid., 87.

52. Clarkson and McCall, op. cit., 277.

53. Anthony Westell, Paradox: Trudeau as Prime Minister (Toronto: Prentice-Hall, 1972).

54. Statistics Canada, Main Economic Indicators.

55. Frank Reid, “Unemployment and Inflation: An Assessment of Canadian Macroeconomic Policy,” Canadian Public Policy, Vol. 6, No. 2, 1980: 291.

56. Jon H. Pammett, Personal Identity and Political Activity, op. cit., 77. This observation was made frequently by young respondents when they were asked why voters in general were attracted to Trudeau.

57. Clarkson and McCall, op. cit., 9.

Clarkson, Stephen, and Christina McCall. Trudeau and Our Times (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1990, 1994).

Gwyn, Richard. The Northern Magus (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1980).

McCall-Newman, Christina. Grits, an Intimate Portrait of the Liberal Party (Toronto: Macmillan, 1982).

Peacock, Donald. Journey to Power: The Story of a Canadian Election (Toronto: Ryerson Press, 1968).

Perlin, George. The Tory Syndrome: Leadership Politics in the Progressive Conservative Party (Montreal: McGill-Queens Press, 1980).

Radwanski, George. Trudeau (Toronto: Macmillan, 1978).

Sullivan, Martin. Mandate ’68: The Year of Pierre Elliott Trudeau (Toronto: Doubleday, 1968).

Stevens, Geoffrey. Stanfield (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1973).

Stevens, Geoffrey. The Player: The Life and Times of Dalton Camp (Toronto: Key Porter, 2003).

Trudeau, Pierre Elliott. Approaches to Politics (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1970).

Trudeau, Pierre Elliott. Federalism and the French Canadians (Toronto: Macmillan, 1968).

Trudeau, Pierre Elliott. Memoirs (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1990).

Westell, Anthony. Paradox, Trudeau as Prime Minister (Toronto: Prentice-Hall, 1972).