FIGURE 8.7b. Pricing Chart - High Detail9

Q. ~

05 O

How to Design Effective Ballroom Style Presentations

It is not enough to choose the right presentation idiom. You also have to make sure that you adhere to the guidelines for your chosen idiom. If you present ballroom style slides with lots of text, or conference room style slides that do not pass the squint test then your results are likely to be worse than anything you have tried before. To ensure that this does not happen to you, this section covers the essential guidelines for effective ballroom style presentations, and the next one does the same for conference room style presentations.

Good ballroom style presentations should have minimal text, perhaps just a brief title, and rich, relevant visuals. The look that you are trying to achieve with ballroom style is that of the evening news: visually rich and thoroughly professional. Therefore your slides should be projected and not printed out, not least because there is little point in printing out slides with very few words on each one, but mostly so that you can make extensive, but always appropriate, use of color, animation, and sound in your ballroom style presentation. How do you know what “appropriate” means? Color, animation, and sound are “appropriate” when they are used to convey or emphasize information. As we noted in Chapter 7, they are inappropriate and should be ruthlessly eliminated when they serve only

to embellish or distract. Use of relevant video segments, photographs, and diagrams are examples of appropriate additions to a presentation.

Because ballroom style presentations use very little text on each slide, you might end up with a lot of slides, perhaps one (or even more) per minute of presentation. So a thirty-minute presentation could have thirty slides, fewer if you spend time talking without visual aids. This is not a bad thing, so long as each slide has relevant content and represents a part of your story. As a rule of thumb, calculate between one and five minutes per slide, but do not plan for more than forty-five minutes of continuous ballroom style presentation, or else you risk having an audience that is dozing in the dark (because projection typically requires you to dim the lights). Therefore the maximum length of a ballroom style presentation is forty-five slides (forty-five minutes X one slide/minute).

How to Design Effective Conference Room Style Presentations

Although most presentations right now are delivered in ballroom style (but badly), relatively few occasions actually call for ballroom style, because this style of presentation is really only appropriate when you have a large audience (say one hundred or more people) whom you are trying to inform or entertain. If you are presenting to a smaller group and/or your goal is to persuade the group in some way—which would seem to be the more common occasion for a presentation—then you should use a conference room style presentation.

A conference room style presentation should look more like an architectural drawing than something you’d see on television. Good conference room style presentations should have lots of relevant detail and text, and should be handed out on paper, never projected. Paper allows a much greater density of detail on your slides, which, if projected, would be mostly incomprehensible. On paper, you can use font sizes as small as 9 point without difficulty, whereas in ballroom style 24-point is usually the minimum safe size.2

Conference room style therefore allows you to put much more information on each page. This facilitates more productive conversations, because all the information for the discussion of the moment is right in front of everyone on a single page; a single printed page can fit the contents of three, four, even ten projected slides. Paper delivery also allows people to write on the presentation, so that they can engage with your content better, and—as Edward Tufte says—it sends a message that you are confident in your content, because you are allowing your audience to walk away with it. Because conference room style presentations contain so much more detail on each page, they tend to have significantly fewer pages—you could spend anywhere between ten minutes to over an hour on each conference room style page.

Conference Room Style and the Problem of Control

Conference style is a very powerful presentation idiom, but it is new to most people. Since it is new, it will take some practice to become proficient in it. However, some

2Many people prefer illustrated paper handouts. Research on subjects with lower reading ability found that illustrated paper handouts outperformed plain text handouts, video, and selfpaced PowerPoint presentations (Campbell, Goldman, Boccia, & Skinner, 2004).

people are reluctant to even try it because they do not like the idea of giving out their slides for fear of losing control of their presentation. If you hand out your slides to your audience, they can read ahead—they do not have to wait for you. But if you project your slides, you decide when to go to the next slide. So with a projector, you keep control. You decide where the audience’s minds will be at any given point.

Or do you? In reality, with a projector, you only have the illusion of control. Certainly, you decide which slide is being projected, and when. But you have little or no control over where your audience ’s minds are. They could be thinking about anything—the problem they left burning on their desk, their last vacation, lunch. . . . And with many projected presentations, they probably are thinking about anything—anything except the presentation, that is.

At least with conference room style slides, you have some feedback as to whether your audience is keeping up with you. You can see whether a person is getting bored and reading ahead, because you can see that she’s turned the pages, or if another person is having trouble keeping up and is falling behind, because he’ s still looking at the previous page. With conference room styles slides, you give up the illusion of control, and in return you get the reality of knowing whether your audience members are still with you.

I think that the concern with audiences reading ahead stems from experience handing out copies of ballroom style slides—which is something you should never ever do, as we noted above. Ballroom style slides, by their nature—with their big fat 30-point text, have very little content on each, and so it is no wonder that your audience will be reading ahead—there ’s so little on each slide. Properly done, each conference room style slide will be so rich that your audience will not want to be reading ahead.

One other benefit of handouts for conference room style presentations is that they avoid the apparent tension between presenter and audience that comes from one having control of the projector, while the others do not. When one person controls the projector, it appears as if he or she is trying to dominate the room. By contrast, when everyone has copies of the handouts, then control over the presentation feels as if it is shared. As an audience member, no one is forcing you to move to the next slide if you are not ready, or to stay on the current slide if you are bored. Also, perhaps most importantly, you can mark up the slides in front of you—deface them if you want—which helps maintain that sense of each audience member being in control. This reduction in tension should be helpful for presentations with emotionally charged or particularly contentious topics.

How Many Slides Should a Conference Room Style Presentation Have?

The quick answer to this question is: as few as possible. Do not assume that each of your S.Co.R.E. cards should become one slide. The goal is to fit the content of as many cards as possible onto one slide, to keep your presentation as brief as possible.

Fewer slides is always better here. Has anyone ever said to you: “I think your presentation was great . . . except that I wish that you had a few more slides”?! I ask this question in every workshop I run, and almost no one has ever had this experience. It is probably fair to generalize that almost all presentations are too long. Therefore, it is a good idea to try to shorten them for a change. When you think your presentation is too short, it will probably be just right.

Fewer slides make for better presentations because they allow for more understanding and richer, more interactive discussions. Your audience can see more steps in your logic on each page in front of them, so they can understand your argument better. People learn better when presentations follow what are called the spatial and temporal contiguity principles: where words and graphics are presented all together, on the same page—spatially— and at the same time—temporally—rather than spread out over multiple pages.3

3Both principles are derived from extensive empirical research.

See especially Mayer (2001) and also Moreno (2006).

When your audience has all the information relevant to a particular discussion right in front of them, that discussion can flow more freely than if they have to keep asking you “Could you back up two slides to the one about, um, cost savings—no, not that one, three slides back I guess , . . .” If you want your audience to absorb and adopt what you are presenting to them, then it is important to allow interactive discussion, which gives them the opportunity to engage with your material and reflect on it. Having everything on one page in front of them allows for this.

But isn’t communication more effective when complex information is presented piece by piece rather than all at once? On the contrary, research indicates that, from an educational perspective, if you break up a complex task into too many steps, learning can be less effective.4

Finally, having fewer slides that you hand out is better because people are limited in how far they can read ahead if it turns out that you are going too slowly. If you have only five or seven pages in total (rather than the forty or so pages that make up an average PowerPoint presentation), then you can spend the time to make each one of them just right.

4A multimedia learning experiment conducted on law students in Holland found that breaking up a learning task into a higher number of steps actually reduced learning efficiency (Nadolski, Kirschner, & van Merrienboer, 2005).

RESEARCH ON THE IMPORTANCE OF INTERACTIVITY

The importance of promoting interactive discussion of your presentation is underscored by the interactivity, reflection, and personalization principles:

• The interactivityprinciple states that “Interactivity encourages the processing of new information by engaging students in an active search for meaning.”

• The reflection principle states that “Students learn better when given opportunities to reflect during the meaning-making process.”

• The personalization principle states that “Personalized messages heighten students' attention, and learning is more likely to occur as a result of referring the instructional material to him/herself.” Interactive discussion gives you an opportunity to personalize your information to individual members of your audience, as you respond to their questions.

See Moreno (2006, p. 65) for more details on each of these principles.

What Is the Ideal Length of a Conference Room Style Presentation?

The theoretical, ideal length of a conference room style presentation is one page—with lots of detail, well laid out. Why? Because if you can achieve the goals of your presentation in one page, why would you use two, or ten, or forty? If you are able to distill your message down to one page, your audience will get the sense that you have really captured the essence of the subject. They will also appreciate (and probably be stunned by) the brevity of your presentation.

You will work through the S.Co.R.E. method described in Chapter 6 to organize your material into a story, and then you will use only as many pages as you need to tell the story. Any extra material that does not fit into your story but might come up during the presentation can go into an appendix. You could have a one-page presentation and a fifty-page appendix. The main thing is that you are not compelling your audience to sit through fifty slides.

One page is an ideal, not a rule. The rule is: use as few pages as possible to deliver your message effectively t When we take this approach in workshops that I have run, participants routinely end up with presentations that are seven, five, or two pages long, and occasionally they do come up with a one-page presentation, where in the past they would typically present between twenty-five and fifty pages. By aiming for the ideal of a one-page presentation, you may not hit it, but you will end up with far fewer pages than you would have otherwise. This is a good thing.

What if you are given a one-hour time slot for your presentation, and you show up with a presentation that is only one page long? One slide, well designed and rich with detail, can easily absorb the interest of a group of people for an hour. It makes interaction and discussion easier: we are all poring over the same page, rather than being frog- marched through fifty slides, and so the meeting tends to be very satisfying and productive. Decisions are made, and people act on them. Finally, if you do finish early, give your audience some time back. Who could possibly be upset with that?

When to Use Multiple Presentation Idioms in the Same Presentation

Sometimes it is appropriate to switch between the two styles within a single presentation. For example, you might provide a conference room style handout at the end of a ballroom style presentation, particularly if you want your audience to walk away with some important details. Or, in the middle of a conference room style presentation, you might pause to project a brief video segment or some images—ballroom style—and then return to the handout to continue the discussion.

This works so long as you are alternating between styles. But don’t ever try to mix the two styles: never, EVER project a conference room style page, or hand out a ballroom style slide. Figures 8.5 and 8.6 show two (admittedly exaggerated) examples of this bad mixing of styles. Figure 8.5 represents an attempt to project (which is only appropriate to

FIGURE 8.5. Bad Example: Projecting a Slide with Lots of Detail

❖ I have so much to tell you, that I'm going to write it all down in the hope that you will get it all

❖ Just to be sure, I am going to read it to you at the same time that you read it to yourself

❖ Little do I realize that your auditory and visual channels will be competing with each other, and so you probably won’t get any of this at all

❖ I might as well have stayed at home

FIGURE 8.6. Bad Example: Printing a Slide with Very Little Detail

ballroom style) a lot of detail (which is only appropriate to conference room style); and the slide fails the squint test, anyway. Figure 8.6 has the opposite problem: printing (conference room) a slide with very little detail (ballroom). And it also fails the squint test.

How Much Detail to Put on Each Slide

The answer to this question may be somewhat counterintuitive, because the most common advice is to “Keep It Simple.” The problem with this maxim as a general guide is that most of the problems you are presenting about are not simple—otherwise why bother making a presentation about them? In general, more detail is better. You want to show, not hide, the details of the complexity of the issue you are addressing. If the issue you are presenting has no complexity to it, then perhaps you do not need a presentation; a simple email or phone call might be more appropriate.

The answer is therefore not “simplicity at all costs,” but a creative combination of what Edward Tufte calls “simplicity of design and complexity of data” (2001, p. 177). You need

to find ways to respect the inherent complexity in your data, while explaining it with a persuasive and comprehensible simplicity.

5Based on two experiments,

Slusher and Anderson (1996) concluded that causal arguments or explanations are more persuasive than statistical evidence.

Showing more detail gives important benefits. Your audience will understand your presentation content better, and you can have more constructive discussions about it. Showing more dimensions of data allows more discussion about possible cause-and-effect relationships, which are critical for effective problem solving.5

Also, detail gives you more credibility, because you are showing your facts, not saying “Trust me, the facts are there.” Sometimes, just the visual impression of lots of detail, well organized, is convincing, even if you audience does not actually read that detail. David Ogilvy, the advertising guru, once asserted: “I believe, without any research to support me, that advertisements with long copy [lots of text] convey the impression that you have something important to say, whether people read the copy or not” (1983, p. 88).

6Concrete words (“factory,” “customer,” “furniture”) are more memorable than abstract words (“compromise,” “coverage,” “illusion”; Walker & Hulme,

1999, p. 1271). Concrete metaphors are easier to understand than abstract metaphors (Morgan & Reichert, 1999).

Genius that he was, he knew the truth without needing research evidence. Advertising research has since shown him to be correct—ads with more detail get more attention, generate more interest, are more convincing, and drive action more effectively.

Using details—particularly concrete details—is another application of the reality principle: always prefer to present evidence that is concrete and particular rather than conceptual and general. Concrete words and metaphors are easier to understand and remember; a concrete metaphor is more like a story than an abstract one because it contains details and texture, which make it more interesting.6

7A meta-analysis of sixteen empirical studies of “powerful” versus “powerless” language, mostly in legal research, found that the former is perceived as more persuasive and credible (Burrell & Koper, 1998).

Concrete details—and concrete language in general—is also more persuasive. Extensive research has found that use of abstractions in language, such as empty (non’ specific) adjectives, hedges (e.g., “sort of” or “kind of”), and intensives (e.g., “very” or “really”), which researchers have labeled “powerless language,” are significantly less persuasive than “powerful language,” which is more straightforward, precise, and therefore

concrete.

RESEARCH ON THE PERSUASIVE POWER OF DETAIL

• Rossiter and Percy (1980) found that specific details of product claims in print advertising (for beer, in their study) were more persuasive than general claims.

• Both business buyers (Soley, 1986) and consumers (Lohse, 1997; Woodside, Beretich, & Lauricella, 1993) find detail more convincing.

• Ads with more specific detail are more likely to be considered by consumers (Fernandez & Rosen 2000).

• Kelly and Hoel (1991), in their study of Yellow Pages advertising, found that in the majority of cases, increasing the amount of copy in the ad was associated with an increased likelihood of the consumer selecting that company over others.

• Armstrong (2008) cites several studies that conclude that, when your message is high-involvement, ads with longer copy (more text) are more attention-getting, generate more interest, and drive action.

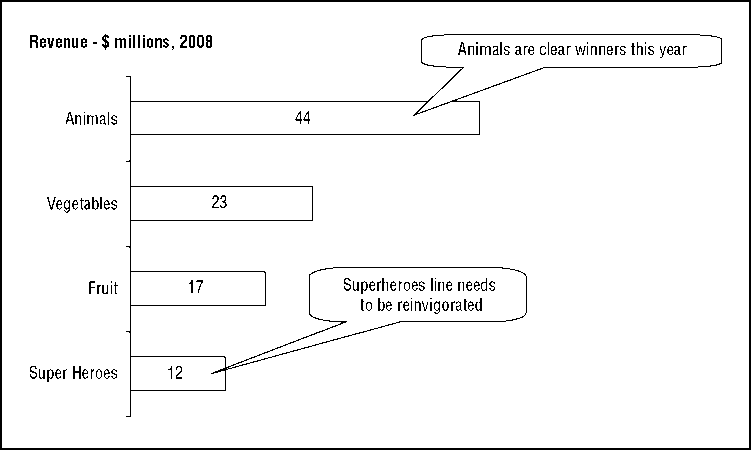

Two kinds of detail that can add concreteness to your presentations are illustrations and numbers. Adding several illustrations to your page can increase audience interest, while adding numeric—quantified—details is more persuasive, because this implies credibility.8

And finally, more detail on each page means that your overall presentation will likely be shorter, because you can put the content of what would have been several slides onto one page; the advantages of shorter presentations were discussed above.

8Using multiple illustrations on the same page made a business advertisement more interesting to its audience (Chamblee & Sandler, 1992). Particularly when the communicator is perceived to be an expert, providing quantified details is more persuasive (Artz & Tybout,1999).

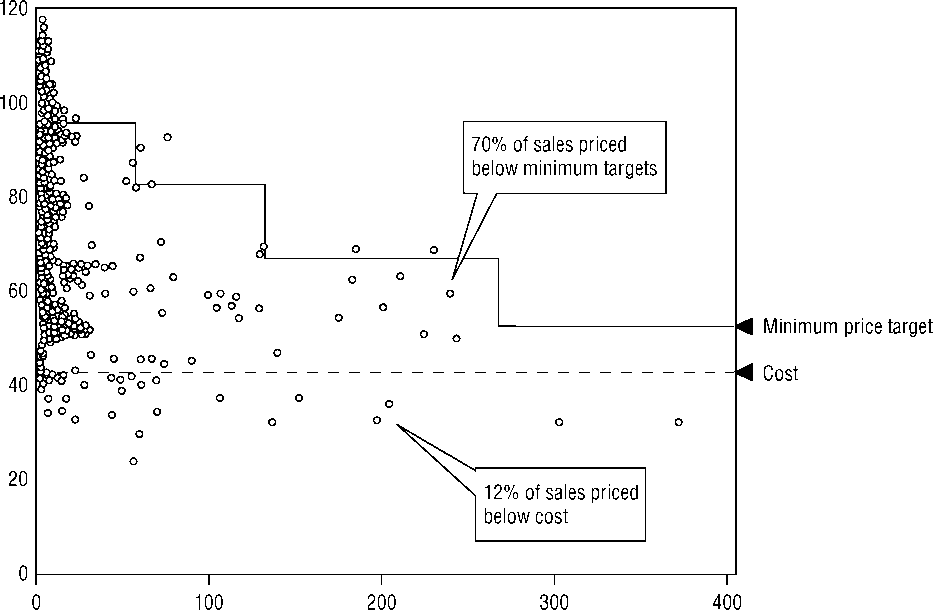

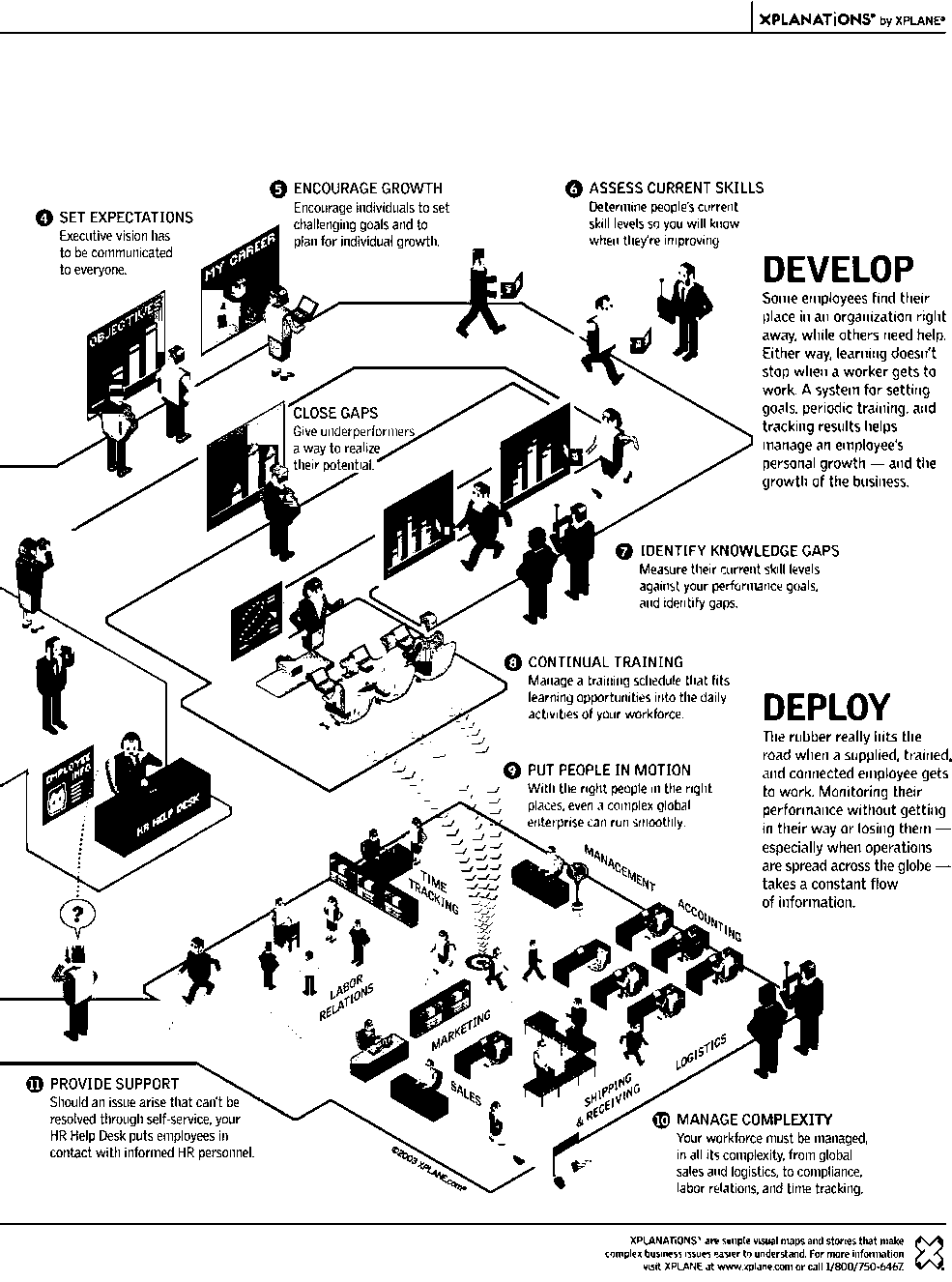

More detail allows you to communicate more information on each slide. Consider the two charts in Figures 8.7a and b t Both present pricing data. Figure 8.7a is very straightforward. The first column shows that findings from this piece of research was that 70 percent of all sales were made at below the minimum target price, indicating poor pricing discipline, and next to it, that 12 percent were sold at below cost, which means that the company is losing money on each of those sales. Clearly, these are concerning findings from the analysis.

Look at Figure 8.7b. It contains a scatter chart, with each dot representing a single sale. The vertical axis shows the relative sales price and the horizontal axis shows the size of the customer who bought it, in annual revenues. The zigzag line across the chart is the minimum price target, and below that, the dotted line shows the cost of each sale.

FIGURE 8.7a. Pricing Chart - Low Detail

cost

If you look above the zigzag line that indicates the minimum price target, you can see that very few of the sales were made above that, which we do know from the first chart. But something else shows up in this more detailed chart. To whom were most of the sales made, at or above the recommended price? To very small customers: you can see them all clustered near the top left corner of the chart. There are very few sales made to larger companies at or above the recommended price, which suggests that customers of any size except the smallest are able to bargain the company down below its targeted price. This is information that was not available in the simple version of this chart on the left.

9Chart based on Bundschuh & Dezvane (2003).

What’s the point? The point is that we are trained to simplify things. But if you are communicating complex issues, do not be afraid of detail’ To extend and paraphrase Tufte ’s dictum: the goal here is simplicity of design and complexity of detail.

Here is another example (Figure 8.8). The occasion for this chart was the retirement of Justice Sandra Day O’Connor from the United States Supreme Court. The newspapers at the time were talking about how she was the justice closest to the center of the court, and the evidence for this was that she tended to agree to with other justices more than anyone else on the Court. Figure 8.8 is an attempt to show this. The chart portrays the percentage of times that Justice O’Connor agreed with each of the other justices; you can see their names across the bottom of the chart. She agreed 71 percent of the time with then-Chief Justice Renquist, 67 percent with Justice Anthony Kennedy, and so on.

FIGURE 8.8. Bad Example: Supreme Court Agreement

Justice O'Connor % Agreement with Other Justices

i-^-1-^-1-^-1-^-1-^-1-^-1-^-1-^-1

Rehnquist Kennedy Souter Breyer Scalia Thomas Ginsberg Stevens

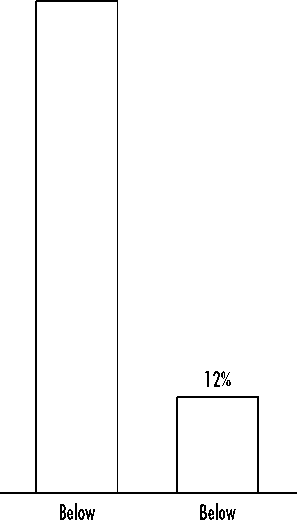

But, of course, what this chart does not show us is how much the other justices agreed with each other, so we cannot conclude, from this chart alone, that Justice O’Conner was the most “agreeable.” Instead consider Figure 8.9, a chart that appeared in The New York Times of July 1, 2005 (reproduced with permission). Down the diagonal are the nine justices on the Court at that time. To see how much any particular justice agreed with any other you follow the row and column that connects them. So to see how much Justice Stevens agreed with Justice Breyer, look at the top left box, and the number there is 62 percent. Thomas and Scalia, 79 percent. Thomas and Stevens, 15 percent. And the size of the circle in each box is proportional to the percentage agreement. If you look at Justice O ’Connor, you can see a lot of larger circles in both the row and column extending from her name.

The third example, in Figure 8.10 ’ is of a fictitious company. Products from this company are laid out on a 2 by 2 matrix, with higher priced products at the top part of the matrix and lower priced ones at the bottom, and with lower market share products on the left, and those with a higher share on the right. At the top left, products A1, ZX80, and PDQ1, these are all higher priced, lower market share products. At the bottom left, products Z1 and S1 are lower price, lower share products. And at the bottom right of the matrix, the X150 and the R2000 are lower price, high market share products.

If you were presenting this information, you could use this chart to show a number of things. You could show that there are no high priced, high market share products, and your audience could conclude that perhaps being a higher priced product is not a good place to be. Maybe, or maybe not; the actual conclusion would depend entirely on the relative profitability of each product—which this chart does not show.

But the bigger problem with a more “impressionistic” chart like this is that it is too easy to challenge. I call this an “i mpressionistic” chart because, like Impressionist paintings, it intends to show only a rough representation of the data, not the actual data itself. And

FIGURE 8.9. Good Example: Supreme Court Agreement

therefore your audience can disagree with its content too easily, because it is all based on judgment. They might argue that A1’s 16 percent share is actually quite high for this industry. Or they may say that the R2000 is actually pretty expensive.

A better approach is to show the details. Look at Figure 8.11’ Again we are using a 2 by 2 matrix. However, this time, instead of allocating the products to quadrants using human judgment, we let the data set speak for itself.

So the products are plotted on a scatter chart, with price on the vertical axis and market share on the horizontal axis. And by turning the chart into a bubble chart, we can add a third variable—the important profitability data. The size of the bubble shows the total profits generated by each product. The picture is now quite different. Instead of favoring lower priced products, your audience is now likely to see that the higher priced products, even though they have lower market shares, overall are generating a lot more profit.

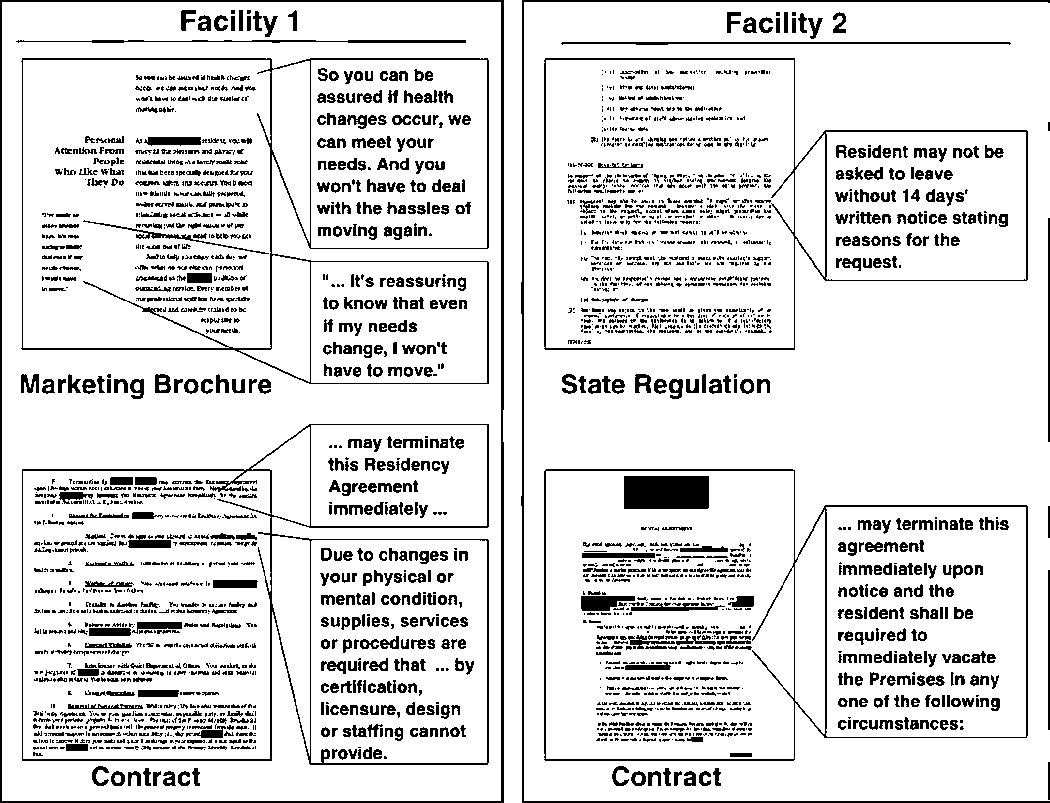

Detail is not only important for quantitative data; it’s also really important for qualitative data. The detail in qualitative data is the richness—or “texture”—that it has. Look at the example in Figure 8.12. This is from the Government Accountability Office (GAO),

FIGURE 8.10. Bad Example: Segmentation

Product Attractiveness Matrix-A

FIGURE 8.11. Good Example: Segmentation

Product Attractiveness Matrix-B

Price/unit - $

0% 10% 20% 30% 40%

Market Share (Bubble size = gross profit $/product)

FIGURE 8.12. Good Example: Qualitative Details

Source: United States General Accounting Office Report on ALF: 1999

which is the U.S. Government’s private consulting firm. It is taken from a report investigating assisted living facilities, and its purpose is to show how contracts in this business tend to contradict what is advertised and also sometimes the law.

The graphic on the left in Figure 8.12 shows an image of a page from a marketing brochure of a long-term-care facility. Some of the text from that page is magnified, to highlight the claim that the facility can handle a wide range of care, so that if the resident’s health conditions should change, he or she would not have to move to another facility. The image below it is from a contract from the same facility, with text highlighted stating that the facility can require a resident to leave if his or her health condition should change. The contradiction is blatant, and well communicated by juxtaposing the details of the two documents. The same approach is used on the right, where text from state legislation requiring facilities to provide fourteen days’ notice before asking a resident to leave is contrasted with an extract from a contract stating that the resident can be evicted with no notice at all.

The details in this example do not prove anything. They are examples: they merely illustrate the point. But examples hold an important place in the storytelling (S.Co.R.E.) sequence (see Chapter 6). Details in qualitative evidence are the visual equivalent of storytelling and have the same fascination for your audience.

How do you include all this detail without overwhelming your audience? By following the guidance of the squint test. If your slide passes the squint test, then the amount of detail on the slide is irrelevant, because the overall message will be immediately evident to your audience, and they will not be put off by the detail. Also, as you might have guessed, conference room style slides will carry lots of detail much more easily than ballroom style slides. Detail is still appropriate for ballroom style slides, though, particularly if it is in the form of detailed photographs or diagrams.

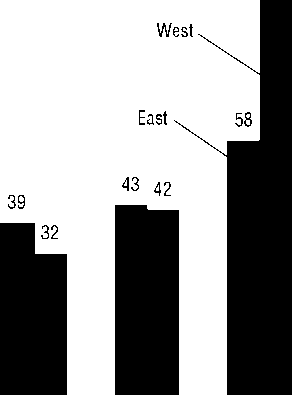

How to Avoid Bad Detail (“Chartjunk”)

There is only one kind of bad detail, and that is what Edward Tufte calls “chartjunk” (2001, p. 107). Look at the two charts in Figure 8.13. Does the one on the right communicate anything more than the one on the left, for all the embellishment that it contains? No, it does not. Worse than that—i t is somewhat harder to read. Research confirms that the addition of this kind of ornamentation hurts communication, because the viewer is distracted and wastes mental energy trying to figure out whether there is any significance to the embellishment.10 The three-dimensional bars, in particular, have been shown in research to slow down viewers’ processing of a graph.11 The harmful effect of irrelevant details applies even beyond graphics. Advertising research has found that adding irrelevant information into an advertisement reduces its persuasiveness.12

10In several studies, irrelevant images and details were found to hinder effective communication (Bartsch & Cobern, 2003; Edell & Staelin, 1983; Feinberg & Murphy, 2000; Mayer, 2001; Moreno, 2006; Myers-Levy & Peracchio, 1995; Slykhuis, 2005).

11In an experiment with eight subjects, Fischer (2000) found that irrelevant depth cues were associated with slower decision times.

12Meyvis and Janiszewski (2002) concluded that consumers look for evidence that confirm product claims and categorize all nonsupporting information—whether it be negative or just irrelevant—as non-confirming.

FIGURE 8.13. Chartjunk: Which Chart Is Easier to Read?

ill 50

90

Sales - $ millions

90

80

70

60

H East □ West

40

30

25

I

20

10

0

Q1

Q2

Q3

Q4

1st Qtr 2nd Qtr 3rd Qtr

4th Qtr

FIGURE 8.14. Bad Example, But for Different Reasons

13Put data values on the top of each bar (Jarvenpaa & Dickson, 1988). Communication effectiveness increases when graphics and text are placed close to each other (Mayer, 2001).

In order to eliminate chartjunk, any detail that is not communicating something unique, or emphasizing something important, should be eliminated from your graphics. In our example, the gridlines can be removed, and the vertical axis also, and instead each of the bars can be labeled with its specific value. This makes it easier for your audience to read the value that each represents than if they have to try to estimate the values by reading them off the vertical axis. The legend can be removed and replaced with direct labeling of the bars, which is easier to read. And the three-dimensional effect, of course, has to go.13

The slide in Figure 8.14 shows a different type of chartjunk. This slide, from a military briefing on the Iraq war, was featured in a book critical of the war and the planning process that led up to it. After the book’ s publication, the image of the slide and the accompanying criticism from the book appeared online, and the slide itself was heavily criticized. Much of the criticism centered on the apparent incomprehensibility of the slide: it is “as clear as mud.”1

We need to be careful about criticizing slides out of context; this was the only slide we could see from a (safe to presume) very long deck, and the buzzwords and jargon on the slide that make it seem so obscure to us are presumably quite familiar to its intended audience. In fact, I do not think that the unintelligibility of the slide is its main problem. To those familiar with the situation, the slide is in fact quite intelligible. The slide passes the “squint test” . flow from left to right is clearly evident, as is the compression of the forces on the outside, funneling the elements in the middle of the slide into the supposed unity on the right side of the slide. And the message is quite clear: a series of pressures will force the disparate elements within Iraq to move toward unity. So the slide does have simplicity of design, of a sort.

The real problem with this slide is that it is lacking complexity of detail. It appears to have a lot of detail—there is certainly a lot of stuff on the slide. But the problem is that all that “stuff” is not actually details. In fact, it is the opposite of details: a bunch of abstractions,

such as “stability,” “resettlement,” and “integrated economy.” Detail implies specifics: this is the role that detail plays in your presentation, bringing it down from the abstract into the concrete, to make it credible and useful to your audience. And this lack of detail was exactly the problem, apparently, that the subordinates who received the presentation of which this slide was a part—in lieu of actual orders—were facing. In the absence of specifics, it was unclear to them what they were actually supposed to do to achieve the goal expressed in the presentation.

How Much Text to Put on Each Slide

The answer to this question depends first on whether you are using ballroom or conference room style, and second on whether you are designing your presentation primarily to be presented live or to be read by others without the presenter. As we mentioned before, ballroom style slides should have very little text, while conference room style slides can have lots more. The amount of text on a conference room style slide will depend on whether your material will be presented live or not. Live presentations can have less text, because the information is conveyed through the presenter’ s commentary. Stand - alone presentations need a lot more text, to avoid any ambiguity (since the presenter is not there in the room to clarify things).

15Annotating a graphic using callouts for important conclusions increase the memorability of those conclusions (Myers-Levy & Peracchio, 1995).

One way to add this text is to use callout boxes: boxes of text with arrows that point from them to the relevant graphic on the page (see Figure 8.15 for an example of a using callout boxes). If your presentation document is going to be used both for a live presentation and a stand-alone document, you should seriously consider making two versions of the document—one for the presentation and one for takeaway. The Extreme Presentation method makes your presentations shorter, so this becomes easier to do, and often it is just a case of creating the stand- alone version first, and then deleting some of the callout boxes for the live version.15

FIGURE 8.15. Callout Box Example

Challenges for a High Performance Workforce

FIGURE 8.16. Bad Example: HR Presentation

High Performance Workforce

• Efficiency begins at point of impact

• Employees with right skills can have huge impact

• Fast, reliable information and systems required to source and deploy workforce

• Cookie-cutter workforce is pure fantasy

• Finding people with right skills requires information, judgment, vision, and resources

• How do you know what kind of worker you need at a given moment?

|

1. |

Plan: Set corporate |

|

objectives | |

|

2. |

Engage and select |

|

employees | |

|

3. |

Equip: Provide needed |

|

tools |

• Some employees find their place in the organization right away; others need help

• Learning doesn't stop once a worker gets to work

• System needed for setting goals, training, and tracking results

|

4. |

Set expectations |

|

5. |

Encourage growth |

|

6. |

Assess current skills |

|

7. |

Identify knowledge |

|

gaps | |

|

8. |

Continual training |

• Rubber hits the road when a supplied, trained, connected workforce gets to work

• Monitoring takes a constant flow of information

|

9. |

Put people in motion |

|

10. |

Manage complexity |

|

11. |

Provide support |

Reward

• Keeping good employees takes new challenges and greater rewards

• Investments in highly productive employees can really pay off

12. Provide incentives

13. Create opportunities

14. Analyze performance against objectives

Any questions?

I t is possible that, if you combine graphics and text well in a stand- alone presentation document, its effectiveness can be equal to that of a spoken presentation, so long as the audience takes the time to study it.16 But, of course, that is the question—will they take the time to study it? Which is why an in-person presentation is more reliably effective: because your audience is present and therefore has already chosen to invest their time in your message.

But is there such a thing as too much text, even in a conference room style slide? In the Introduction to this book, we saw how presenting typical bullet-l ist slides along with a verbal explanation is worse than speaking without slides at all or presenting slides without speaking because audiences have difficulty listening to you and reading the slide at the same time. Won^ this be just the same for conference room style slides, even if they pass the squint test?

I think that the answer is No—because of the squint test. When you present a bullet- list slide, your audience does not know what is on that slide until they read at least a few of the bullets. So they are going to start reading those bullets as soon as you show them the slide, even if you are trying to explain something to them. When you show them a well-designed slide that passes the squint test, though, as soon as they see the slide they have some idea of what it is about, and therefore they do not have to read all the details and they can focus on what you are saying.

Look at the sequence of slides in Figure 8.16. There are twelve slides in this presentation. If you squint at any of these pages, you see lots of bullets, but nothing beyond that. What this is, in fact, is a presentation on the stages in the human resources (HR) process in a typical company: hiring, developing, deploying, and rewarding.

Figure 8.17 shows a much more interesting and effective way to present the same information. The HR process is clearly evident here. It starts at the top left, with new employees being engaged by the company; you can see them walking through the door. Through several steps of on-boarding, they reach the development stage, at the top right of the page. They are then deployed into the various functions in the company, at the bottom right, and through several more steps are rewarded, on the bottom left, and promoted— you can see some of them climbing the staircase to their next position.

The point of including this graphic is not to suggest that everything you do should look this polished. This graphic was created by Xplane Inc., a company that specializes in such things, so you should not expect to meet their standards in your daily work. It does, however, show just how much detail you can put on a page and still be very comprehensible and effective. You can imagine what a rich and involved discussion you could hold, just using this one page. (If you happen to be just flipping through this book right now and noticed Figure 8.17 and think that it looks too “busy,” then go back and read this chapter from the beginning. You will then understand the power of the detail in it.)

16Ginns’ (2005) meta-analysis of forty - three different experiments found that when participants were able to study the presentation on their own, results can be equal to a live presentation.

FIGURE 8.17. Good Example: HR Presentation

FIGURE 8.18. Combining Graphics and Text

Source: From WHAT DO PEOPLE DO ALL DAY? by Richard Scarry, copyright © 1968 by Richard Scarry, copyright renewed 1996 by Richard Scarry II. Used by permission of Random House Children’s Books, a division of Random House, Inc.

Whether to Combine Graphics and Text on the Same Slide

It is a good idea to put text and visuals close together.17 Remember, though, that in any case, ballroom style slides should have very few words. In conference room style slides, which work well with lots of text, you will want to make sure that your text is placed close to the relevant graphics whenever possible. Figure 8.18 shows a page from a popular children’s book. Note how closely integrated the text and visuals are. This is the kind of thing you are trying to create for your conference room style slides.

How Exactly to Decide What Goes on Each Slide

What you should do now is work through your S.Co.R.E. cards and see how many you can fit on each slide by grouping your cards. Begin with your first card, think about how much space the information it represents would take on your slide, and then keep on adding cards until you think you will have filled your first slide. Then move on to the next slide, working through the subsequent cards, and so on, until you’re finished. Your situation card will typically take up very little space—it usually represents just a spoken comment. Ditto for your complication cards: unless they represent data about the complication, or images to illustrate it, your complication is usually also just spoken; it is your transition between slides, or between different points on your slide (e.g., “You are probably thinking now that this all sounds very expensive; well, let me show you why that is not the case”).

At this point you should have a series of piles of cards, each pile representing a slide. What you’ll need next is a rough sketch of the layout of each slide—so that the layout of the page supports the main message of the page. One effective way to do this is to try to write a one-rentence version of the main point of each page. The discipline of trying to craft a one-sentence message can be a good test of your presentation: Is each message new to your audience, interesting, and important for them to know? Will it be solidly supported by the details you will put on the page?

If you can’t answer yes to each of these questions, then it is probably not worth drawing a page. (See Figure 8.19 for a checklist approach to this.) You may want to go back through

FIGURE 8.19. Checklist: Before Drawing a Slide

17When corresponding text and illustrations are placed near each other, effectiveness increases. It is better to show corresponding illustrations and text simultaneously than sequentially (Mayer, 2001).

Unless you can answer “yes” to all the following questions, you are not really ready to draw a slide.

□ Can I write a one-sentence summary of the main message of the page?

□ Will this message be solidly supported by the information and details on the page?

□ Will this message be new to my audience?

□ Will this message be interesting to my audience?

□ Is this message important for my audience to know?

the Extreme Presentation process and change some things. Begin by trying the one-sentence exercise again. Can you rewrite the sentences so that they are newsworthy, interesting, important, and well supported by your data? Sometimes we undersell our own content, and rephrasing our messages can help avoid this. But on other occasions we may have to go back and do the S.Co.R.E. card exercise again. Or maybe you need to focus on a different business problem. You might even have to go back and revisit the objectives for the presentation, perhaps because the data you have does not support as aggressive an objective as you set initially. But this iteration is good—it just makes your presentation stronger.

Once you have a one . ientence message for each page, think about what page layout design would best communicate or support this point, and then sketch the layout for each page, using paper and pencil. We noted above that to ensure that your page passes the squint test, you need to make sure that the layout of the page reinforces the main message of the page. This is what you are doing here. Appendix C contains thirty- six examples of slide layouts that pass the squint test. (PowerPoint versions of these layouts are available at www.ExtremePresentation.com.)

Rather than drafting your layouts in PowerPoint right now, it is probably better to hold off from using any kind of presentation software a little longer, because inevitably you will spend too much time designing slides at this rough draft stage, and therefore you will be unwilling to toss out earlier versions to try again.

Once you have a rough sketch of the layout of each page, place the sketches side-by-side across your desk, and you will have a storyboard for your presentation. Scan this storyboard to make sure that there is enough variety in page layout, from slide to slide. If there isn’ t, this may be an indication that your presentation is repetitive; consider combining some of the pages or changing their design.

When we do this exercise in our workshops, we almost invariably come up with presentations with single-digit page counts—where the typical presentations were between twenty-five and fifty slides long, with 100+ page presentations not unheard of.

Before going any further, you may wish to review the front-to-back Extreme Presentation case study of “SuperClean Vacuums” in Appendix B.

The Importance of “Roadmapping"

When you use lots of detail on your slides, particularly conference room style slides, you will need to guide your audience’ s eyes across each slide. There are three things you can do to help with this. First, you can number the elements of the page in the order that you want your audience to look at them. Second, you can give them spoken guidance, to help “roadmap” the slide for them. As you present the slide, say, for example, “ First look at the top left of the slide—the chart there shows the increase in employee attrition. To the right of that, you can see. . . .” And so on. Finally, you should lay your slide out so that there is a natural flow around the slide. This does not have to be always from left to right,

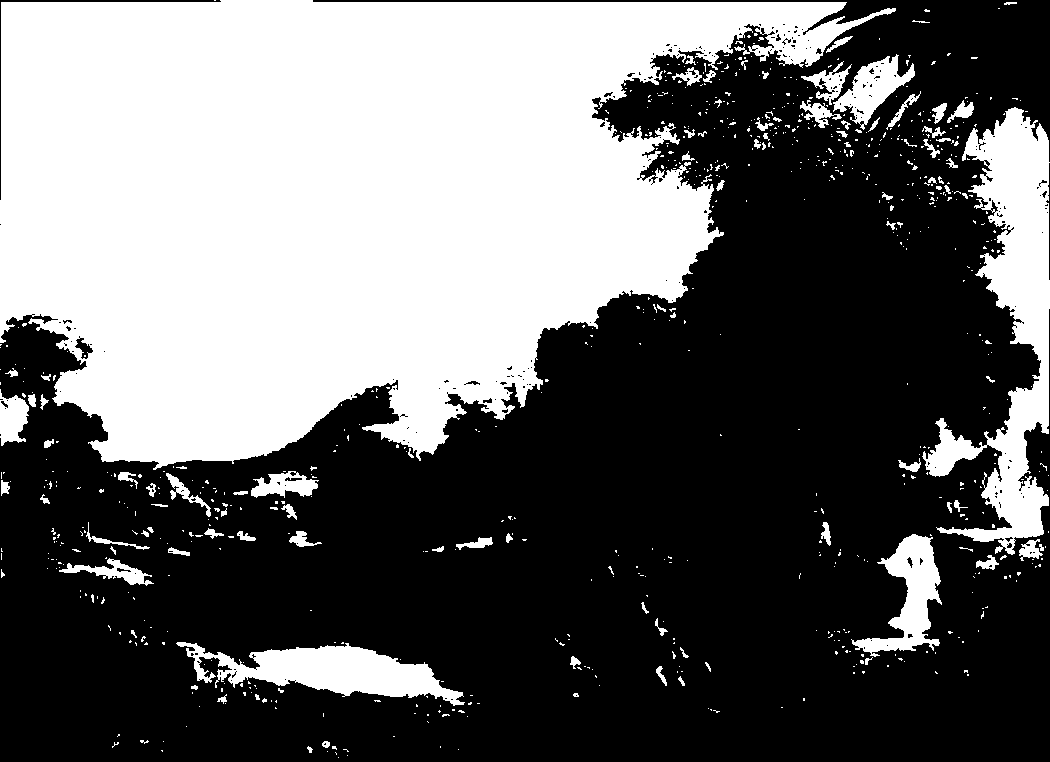

FIGURE 8.20. Thomas Cole’s “Voyage of Life” Series, “Youth”

Source: Thomas Cole, The Voyage of Life: Youth, Ailisa Mellon Bruce Fund, Image Courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

or from top to bottom. In fact, if you can vary the flow from slide to slide, it makes for a more interesting presentation.

We can see such varied flow in good artwork. Consider the Thomas Cole painting in Figure 8.20. This beautiful painting, hanging in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., is part of a four-painting series called “The Voyage of Life,” all painted in 1842. The title of this particular painting, the second in the series, is “Youth.” First, look at the angel at the bottom right of the painting. Next, look at the hero of the painting, the youth to the left of the angel, who is setting off in the ship of life. The river, flowing to the back left of the picture, seems like it will take the youth toward the castle in the clouds, which represents his youthful dreams and ambitions. There is indeed a path through the fields beyond, barely visible, and seemingly heading toward this castle. But, in fact, the river itself take a sharp turn before that path and flows across the middle of the painting, behind the trees, to the right side, and appears again above the angel. The mist above the river there gives a hint of what is to come in the next painting:

a waterfall, with the now older hero cascading down helplessly in his boat, representing the turbulence and doubts of adult life.

Notice the flow we have followed. We started at the bottom right, moved across the bottom and up the left side of the painting to the upper left (the castle in the clouds), then back down across the middle and out the right side. On your own slides, any flow will do, so long as it fits the content of your page, and so long as you guide your audience clearly. Ideally, you will want to vary the flow from one slide to the next, which is more interesting than having every slide read from top to bottom or left to right.

18www.Powerframeworks.com is a subscription site that offers over a thousand different layouts, many of which pass the squint test.

At this point, you are ready to create your slides. Create your own layouts, or use any from Appendix C. Incorporate all the elements you gathered in Chapter 7 into these

layouts.18

Once you are done with this, there are certain elements that are important for every page: title, guide marks, annotations, source, and page number. These are illustrated in Figure 8.21. The title of the page should, like the layout, reinforce the main message of the page. This will be helpful in your presentation and also ensures that the point of the page will not be misunderstood when people read your handout when you are no longer around.

If you need it, you can also add a subtitle. Some people—from certain consulting firms— have a habit of putting a descriptive title at the top of the page and the conclusion or main message at the bottom. This seems to me to give the impression that you weren^ really sure what the point of the page was until you finished it. Better to start out with the point, and then have everything on the page reinforce it.

The importance of “roadmapping” was mentioned above. Using numerical or alphabetical guide marks can help with this. You can direct your audience to “Look first at box .a, . ” for example. As noted above, callout boxes or annotations are helpful for drawing attention, and also for ensuring clear communication to people who read your handout without the benefit of the presentation.

Finally, make sure that each page lists the source for the data on the page—this is important for credibility—and also that each page is numbered. If you are handing out more than one page, then you need page numbers to ensure that everyone is “on the same page.” (Figure 8.22 contains a post-checklist for evaluating each of your slides.)

FIGURE 8.21. Final Details

FIGURE 8.22. Checklist: Evaluating Your Slides

Your page is not complete until you can answer “yes” to each of these questions:

□ Does the layout of the page reinforce the main message of the page?

□ Does the page have a title, and does the title reinforce the main message of the page?

□ Do all the elements on the page reinforce the main message of the page, as expressed in the page title?

□ Does the page contain lots of relevant detail?

□ Is your page properly “roadmapped”? (Are the elements on the page numbered in the order that you want your audience to look at them?)

□ Are the data sources identified?

□ Is the page numbered?

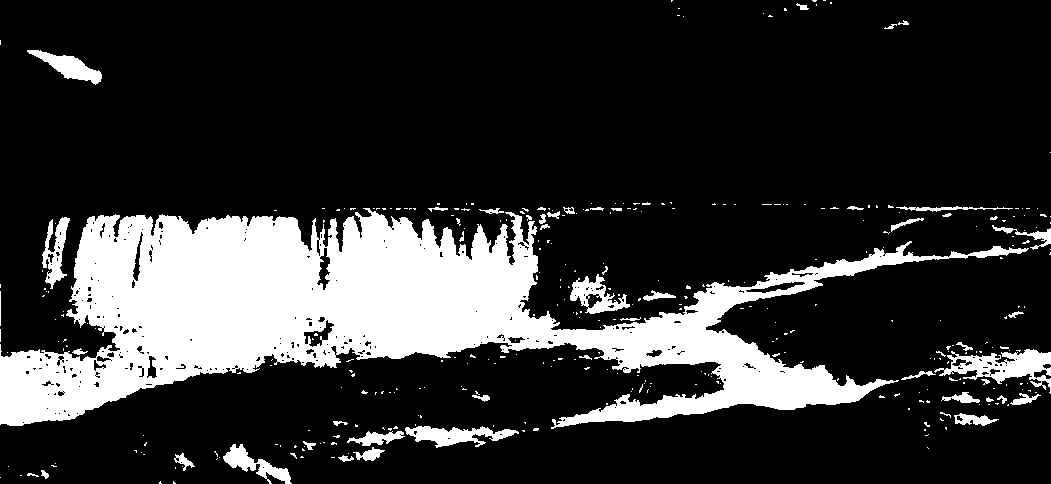

FIGURE 8.23. Frederick Church’s Painting of Niagara Falls

In the Collection of The Corcoran Gallery of Art. Accession Number 76.15. Artist: Frederic Edwin Church. Title: Niagara. 1857. Medium: Oil on canvas. Dimensions: 42 1/2 3 90 1/2 inches. Courtesy of Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. Credit Line: Museum Purchase, Gallery Fund.

It takes effort to create excellent visual communication—to find a good combination of simplicity of design and complexity of detail. Look at the picture in Figure 8.23. This is Frederick Church’s famous painting of Niagara Falls. It represents an impressive demonstration of simplicity of design and complexity of detail. Church put a tremendous amount of effort into this painting. He made six separate visits to Niagara Falls. He drew hundreds of preliminary drawings. He painted twenty-one trial “sketches”—which were really complete oil paintings in themselves—to try to out different angles, times of day, and so on. The final version, which hangs today in the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C., and is seven-and-a-half feet wide, took him six weeks to paint (Johnson, 1998).

What’s the point here? If you’ re working on getting good detail into your presentation, you need to put a lot of effort into it. Not necessarily as much as Frederick Church put into his painting, but more than we usually do in banging out the typical PowerPoint slides. This is because we are not just putting in the detail, but we are also organizing the detail so that it makes sense to the viewer. Fortunately, since you are creating far fewer slides, and perhaps even only one, then you can spend a lot more time on each, and very likely the total amount of time you spend on your presentation will be less than you would otherwise—and yet your presentation will be far more effective.

We are almost finished. But after all this work, someone in your audience could still surprise you with some unanticipated opposition and wreck your presentation. What can you do to avoid that? The last chapter in the book will address this question, and also discuss how to measure your presentation’s effectiveness.

THE FINAL PART OF THE BOOK includes two more steps, from the politics and metrics dimensions, respectively. It is important to begin each presentation with an understanding of the audience and your specific objectives for them, and likewise it is important to end it with another look at the larger audience for your proposal, and with measurement of whether you achieved your objective. This is why Parts I and V of this book are both devoted to politics and metrics, rather than one being focused on each—because you want to start and end your presentation with both.

The next chapter, Chapter 9 , presents the last two steps in the Extreme Presentation™ method. The ninth step, a politics question, asks who beyond your immediate audience has to play a role in your recommendations being implemented. The tenth and final step is a metrics question: How will you know whether your presentation is successful?

Satisfying Your Stakeholders and Measuring Success

Step 9: Identify Any Potential Roadblocks to Achieving Your Objectives, and Make a Plan to Deal with Each

9

Not infrequently, some of the people who are necessary for the successful adoption and implementation of your recommendations will not be in the room during your presentation. If you want to be sure of success, you need to identify these people and create a plan to get them to agree to the steps that you need them to take if your recommendations are to bear fruit.

Think through each of the critical decisions that have to be made in order for your recommendations to be implemented and who needs to make each of those decisions. Think also about whether there are any people who, if they decided that they did not like your ideas for any reason, could block their implementation. These are your stakeholders for this particular project. Make a list of all these people. You will need to approach those who are not going to be in your audience, preferably before your presentation. You may also want to approach some of the more important ones who are going to be in your audience to try to “pre-sell” them on your ideas.

FIGURE 9.1. Stakeholder Analysis Example

|

Whose help will we need for our recommendations to be implemented? |

Jane |

Joe |

|

What must each of them think or do for the recommendations to be successful? |

Agree that the brand investment is worth'a test |

Agree that hecan/do without the incremental funding/ for his salesforce |

|

Where do they stand on this? |

Currently doesn’t agree |

Currently doesn’t agree |

|

What do we need to do to close the gap? |

Private meeting to go over the data in more detail |

Workon/hisboss, because Joe himself will never agree to this |

Once you have your list of stakeholders, the people whose buy-in you need, write down beside each name what the person needs to think or do for your recommendation to be a success, and where you think he or she stands right now. Then create a plan for how you will influence each, and schedule meetings accordingly. (See Figure 9.1 for an example; a blank form is included as Worksheet A.7 in Appendix A.) Then move on to Step 10.

Step 10: Decide How You Will Measure the Success of Your Presentation

The final step in the Extreme Presentation™ method is to measure the success of your presentation. Why should you bother to measure success? At one level, the success or failure of your presentation should be obvious rather quickly: either your audience did what you asked them to do, or they did not. Informally, another measure of success is to observe the quality of the discussion that accompanied or followed your presentation. If your audience starts to work out the implementation details of your proposal during your presentation, then you know you have succeeded.

1See Brinkerhoff’s Success Case Method (2003; 2006) for a detailed approach to measuring training effectiveness.

In addition, you may want to be more deliberate in how you measure success. You have already taken the most important step in measuring your presentation’s success, and that was back in Step 2, where you wrote clear and specific objectives for how you want your audience to change what they are thinking and doing with respect to your subject. To measure success, you want to know whether you have achieved these objectives. This is particularly important for a training presentation; for a presentation proposing an idea, recommending a course of action, or pitching a product or service, you want to know for yourself how successful your presentation was, but for a training presentation you typically also need to know to prove to others who have paid for your presentation.1

At the beginning of the book we mentioned that the Extreme Presentation method takes a marketing communication approach to presentation. The measurement step is just an extension of this analogy, and it suggests one additional goal beyond changing what your audience is thinking and doing. To know whether marketing is effective, we don’ t just measure changes in attitudes and behaviors—we also want to measure the change in brand or relationship equity. This allows us to determine whether our marketing efforts are strengthening our brand or, alternatively, whether they are just cashing in on it and therefore weakening it. Think of it in personal terms: If you try to convince people you know to do something, they may do it because you have convinced them that it would be good for them to do it, or else they may do it just as a favor to you. In the former case, your relationship may be strengthened because you have given them some useful information that allowed them to do something new; in the latter case your relationship is likely weakened. Too many such requests for favors and your friends will no longer be returning your phone calls.

It works the same way for presentations: we want each presentation to not only achieve its attitudinal and behavioral change objectives, but we also want each presentation to strengthen our personal credibility with our audience, so that the next presentation with the same audience achieves its goals more quickly and efficiently.

One way to gather all this information is to announce to your audience, at the end of the presentation, that you are working on an initiative to improve the impact of your work and that you would like to send them a very brief, less- than - one - minute online survey. Gain agreement from everyone in the room to respond to it, to increase the chances of receiving a good response rate. Then email them a link to a survey by the next day at the latest. The survey should have a few simple questions, which will cover these A-B-C’s:

* Attitudes: ask them to what extent they agree/disagree with a statement or two that describes the “thinking” that you are hoping to achieve with your presentation.

* Behaviors: ask them to rate the probability that they will undertake a particular action or set of actions (these actions representing the “doing” that you are trying to get them to do).

* Credibility (personal “brand equity”): ask them to rate their willingness to attend another presentation of yours, and whether this willingness has increased, decreased, or remains the same as a result of this presentation.

In all cases, however, do not tell you audience before your presentation begins that you will be asking them to evaluate your presentation at the end, because it may foster an (unnecessarily) critical mindset in your audience to your whole presentation. Only announce your request for feedback at the end.2

For more important projects, you may also want to send a similar survey again a few weeks, or months, after your presentation, to ask whether they have actually taken the actions they said they would.

Once you have decided how you will measure your success, you have completed the tenth step. Designing a presentation is an iterative process: if you have time, go through the method, the ten steps, one more time quickly, to see whether there is anything else you need to change. The next chapter, the Conclusion to this book, has a “ quick ” version of the ten steps that you can use for your final review.

2Consumer research suggests that informing customers in advance that they will be asked to evaluate something tends to reduce satisfaction, because they tend to focus on the more negative points (Ofir & Simonson, 2001).

Ricks, (2006). See also

http://armsandinfluence.typepad

.com/armsandinfluence/2006/08/

death_by_powerp.html and

watercoolerconfidential/2006/09/

death_by_powerpoint.html.