Spaulding started flinging folders back into the briefcase as fast as he could, but she was already almost at the door.

The footsteps stopped, the doorknob rattled—and a shrill voice rang out.

“Yoo-hoo! Desdemona, Liebling! I was just coming to speak to you!”

Spaulding slumped with relief. Mrs. Welliphaunt would yak at Dr. Darke for ages. He straightened up the folders and carefully shut the briefcase, then slipped into his usual seat in front of the doctor’s desk.

In the hallway, Dr. Darke gave a loud sigh. “What is it, Welliphaunt? Is this regarding whatever your son was calling for? He hung up before I got to the phone, and there was no answer when I called back.”

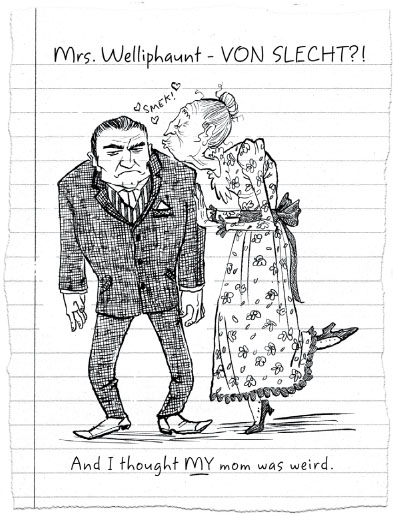

Spaulding’s mouth dropped open. Her son? Mrs. Welliphaunt was Von Slecht’s mother? He shuddered. It was almost enough to make him feel sorry for Mr. Von Slecht.

“No, I haven’t any idea why Werner called you,” Mrs. Welliphaunt said. “Unless perhaps it was about Griselda. He was in a bit of a flutter about her this morning—he’s convinced she’s not well.” A hint of irritation crept into her voice. “You know how foolish he is about that woman.”

Dr. Darke snorted. “I know better than anyone.”

“I was coming to speak to you about the Meriwether boy—he won’t be at his appointment. He hasn’t been in school today.” Mrs. Welliphaunt lowered her voice. “I suspect our little plan is working. The poor dear is quite the laughingstock. I doubt he’ll continue snooping, and even if he does, he certainly won’t be listened to. Everyone is now well aware that he’s a deeply troubled boy.” She gave a dainty giggle. Spaulding clenched his fists.

Dr. Darke sniffed. “I still say my plan would have been much easier. I really can’t fathom why you and Werner are so squeamish about it.”

Mrs. Welliphaunt gasped. “I am a teacher, Desdemona! I care about young people. I would never allow harm to come to one of my dear students. Unless it was completely necessary, of course.”

“Oh, what rot,” Dr. Darke snapped. “As if you care any more about teaching than I do about these ridiculous counseling sessions. If that’s all, I’ll be getting back to the factory. I really don’t know why I waste my time here at all.” Still grumbling, she stomped into the office and slammed the door in Mrs. Welliphaunt’s face.

Spaulding felt his palms start to sweat as Dr. Darke turned from the door. He tried to keep his voice steady. “Oh, hello, Dr. Darke. I’m here for my session. I had to miss morning classes for a—um, a doctor’s appointment, but I’m back now.”

Dr. Darke didn’t reply. Her razor-sharp gaze slid from his face to the closed briefcase.

Oops. It had been open when he came in.

“Spying again, were we?” Dr. Darke said.

She crossed to her desk and leaned on the edge of it in front of him. Spaulding gripped the arms of his chair nervously. But the doctor merely picked up a nail file and examined her perfectly polished fingernails. She gave the edge of one a few delicate swipes with the file.

“You fancy yourself quite the little detective, don’t you? If I actually wanted to counsel you”—she curled her lip at the thought—“I’d tell you to stop trying to impress your parents. They obviously don’t care what you do.”

Before he could respond, she tossed the file aside, leaned down toward him, and seized his jaw in an iron grip. She tilted his face from side to side, scrutinizing him. Her red fingernails dug painfully into his skin. He thought she’d look angry, but instead she was smiling. And somehow that was much, much worse.

After what seemed a very long time, she leaned in until her face was so close he could feel her icy breath. He tried to lean back, but her fingers tightened until his jaw creaked.

“And if you’re still tempted to snoop,” she said, “just keep in mind—I am watching you.” She shoved him away, hard, and strolled over to her own chair.

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” he said shakily. “You and Mrs. Welliphaunt are the ones who told me I needed counseling. I’m just doing what I thought I was supposed to.”

The doctor stared at him, her eyes as cold and flat as two dimes. “You’re obviously beyond help. Your sessions are over. And the next time I catch you snooping, you will not get away from me alive. Now get out.”

He got out.

His heart was pounding and his hands were shaking as he stepped outside. He’d gotten information, all right. But Dr. Darke knew. She knew everything. And he had no doubt she was ruthless enough to do exactly what she’d threatened.

Yet as he hurried across the parking lot to his bike, a little of the tension drained away. He’d gone right into the lion’s den and come out unscathed. He scratched at his jaw as a small smile crept across his face. Katrina thought she was intimidating? She’d crumble if she ever faced Dr. Darke the way he just had.

Just then, the sun came out from behind a cloud and gilded the school buildings and the bare trees. It wasn’t as warm as it looked, but he turned his face toward it, breathing easier with every step.

His jaw itched again. It felt like an insect was crawling on him. He paused to check his reflection in the side mirror of a car—and gasped in shock.

A row of deep, blood-red crescents scored his skin, four on one side and one on the other.

He angled his head to see them better, rubbing gingerly at his skin. He forgot all about the odd little itch. And he didn’t notice that right where the itch had been—just above the fingernail gouges—a tiny, silvery speck glistened in the momentary ray of sunlight.

Then the sun went back behind the clouds, and the speck turned nearly invisible again as it wriggled its way up toward his ear and deeper into hiding.

The moment homeroom was over on Monday morning, Kenny ambushed Spaulding at his classroom door.

“I’ve been waiting to talk to you forever! Why weren’t you in school on Friday? Why were you invisible all weekend? I came by your house like a million times but no one ever answered the door.”

Spaulding sidestepped him and kept walking toward his locker. “I had homework to catch up on.”

“Yeah, right. You finish all your homework before school even gets out for the day. Something happened while I was out sick, didn’t it? Katrina knows all about your parents now, for one thing. Were you trying to impress her or something? ’Cause it definitely did not work.”

That was for sure. She’d spent all of homeroom with her phone out, making everyone watch the most embarrassing clips from Peering into the Darkness she could find. (Mrs. Welliphaunt had suddenly and conveniently become blind to students goofing off.) And Spaulding had an inkling that the hilarious new nickname for the show everyone was using—Peeing into the Darkness—was Katrina’s doing as well.

He stifled a sigh. “Marietta told her.”

Kenny gasped. “No! That’s too low, even for Marietta. Are you sure? Maybe she just found out somehow.”

“I’m sure. And I’d rather not talk about it, thank you.”

“Dude, don’t take it out on me. You’re, like, shutting me out because they’re jerks. I didn’t do anything.”

Spaulding edged away. “Look, it’s only a minute till the bell rings. We’ll talk some other time.”

Kenny raised his eyebrows. “Some other time? What’s that supposed to mean? How about, like, the second school gets out, duh?”

“I don’t know. I might not be home.”

The bell rang, saving him from further awkwardness. He hurried away, pretending not to notice Kenny still standing there staring at him.

Spaulding chewed his nails all through history class, not hearing a word of Mr. Robards’s lecture. He felt bad about what had happened with Kenny, but he couldn’t let himself soften.

No matter how nice Kenny acted, what happened with Marietta had opened Spaulding’s eyes. Sure, his plan had worked, and he’d convinced some kids to spend time with him because they were interested in the mystery he’d uncovered. But he hadn’t made real friends. They only cared about the revenants and the ghost and the haunted serpent. They didn’t care about him. Well, now he knew better. From this minute on, he was in it alone, as he should have been all along.

All he had to do was find concrete proof there was black magic going on in the factory. Once he revealed that to his parents, they’d take him back, and he’d move away from this town forever.

The sound of muffled snickering broke into his thoughts. He jerked his head up to find Mr. Robards sneering at him.

“Well, Mr. Meriwether?”

“I’m sorry?”

“Oh, goodness no! I’m sorry our poor little history class is too dull to hold your attention. Since you aren’t interested in responding to my question, perhaps there’s a topic you would rather address—red mercury, or black magic, or .. . . or . . .

the bogeyman, perhaps!” Mr. Robards was so indignant he was sputtering.

Spaulding sighed. “No, Mr. Robards. I’ll pay attention now, sir.”

The history teacher resumed the lesson, though he continued to shoot Spaulding frequent dark looks. Spaulding tried his best to appear attentive—but his mind was buzzing again, and not with thoughts about history class.

Red mercury.

He couldn’t believe he hadn’t thought of it sooner. When he’d brought it up to Mr. Robards before, he hadn’t taken it seriously; he’d just thought it was an interesting bit of folklore. But compared to ghosts and the rise of the living dead, the existence of red mercury no longer seemed like such a stretch.

It fit with what Marietta had said about Blackhope Pond. The pond was artificial, a by-product of mining, and full of mercury. She’d also said all the ley lines intersected there. Red mercury was supposed to be formed when regular mercury underwent an alchemical transformation. What if the pollution in the pond combined with the energy from the ley lines was creating red mercury? That would explain why his cell phone went haywire there; electronics were supposed to be affected by red mercury.

It would explain something else, too. Red mercury was extremely rare—so rare most people would say it didn’t even exist—and that, combined with the powers it was supposed to have, made it very valuable.

Valuable enough to interest a powerful businessman. Valuable enough that someone might have an entire business built on secretly collecting it.

Spaulding’s teeth clacked against each other as his bike bounced down the old gravel road leading to Blackhope Pond. The moment he’d gotten home from school, he’d grabbed his bike and left. (He did stop in the kitchen, despite feeling ridiculous, to pour a handful of salt in his pocket. Lately, some of his parents’ ideas didn’t seem so stupid.)

He made sure he was gone before Kenny showed up. He didn’t want to talk things over or listen to Kenny try to pretend they were really friends. It was easier this way.

At the clearing, the pond was as black and silent as ever. He scanned the woods carefully for anyone hiding there, undead or otherwise, but nothing moved. The only sound was leaves crunching under his feet.

He pulled out his phone. It didn’t have any reception, but that was normal for being this far out of town. Since he was close to where it had acted peculiarly before, he decided to keep it out and watch it for any strange activity. He held it in front of himself and kept one eye on it as he walked even though it made him feel like an extra on Star Trek exploring an alien planet and waving a tricorder around. Thank goodness no one could see him.

But as he thought this, the feeling of being watched crept over him.

At the same instant, his cell phone blared a discordant ring tone he’d never heard before. Spaulding flinched, and the phone slipped out of his hands. It landed faceup, the screen blank. No incoming call. The ringing switched abruptly to vibrate and then stopped altogether.

He wiped his palms on his jeans and retrieved the now-silent phone. So it hadn’t been a fluke when it had acted weirdly before. That must mean he was getting close to—

Snap!

A branch broke nearby. He spun around, heart pounding.

A little distance away, a sheepish face peered out of the bushes.

“Hey,” Lucy said with a feeble wave.

“Jeez, Lucy.” Spaulding slumped over and put his hands on his knees. “For the last time, quit doing that!”

She stuck her lip out. “But I wanted to make sure you were okay! I saw you leaving all by yourself, and I was worried.”

“You came out here just to see if I was all right?”

“Sure. I tried to get Marietta to come too, but she was acting all weird for some reason. Sorry it’s just me.”

“No—I’m glad it’s just you.”

Lucy’s face lit up. “You are?” She burst out of the bushes and ran over to throw her arms around him. Daphne’s case slammed into the back of his knees as he gave Lucy an awkward pat on the back.

Lucy pulled away and glanced around. Her smile wavered. “But, um . . . isn’t it kind of . . . dangerous out here?”

Spaulding’s heart sank. Just because it was a relief for him to have company didn’t mean he could put Lucy in danger. “You’re right. You have to go home. I can’t let you be out here.”

Lucy’s mouth fell open. “Let me? Let me? You’re as bad as Marietta—ever since our parents divorced, she thinks she has to protect me from everything. But at least she has the right to boss me around. She’s my sister! You can’t tell me what to do.”

“I’m not bossing you around, Lucy. I just don’t want anything to happen to you because of me.”

“It isn’t ’cause of you—I’m making up my own mind. This way, we can look out for each other while we . . . um, what are we doing out here again?”

Quickly, he filled her in on his theory about the red mercury.

Lucy pushed her glasses up her nose and looked doubtfully at his phone. “I don’t get it. What’s the point of this red mercury stuff, even if it is here? What’s it do besides mess up phones?”

“Well, the folklore says it can do everything from curing illness to turning common metals into gold to giving power over the dead. I think Von Slecht is collecting it from the pond. I was hoping there might be some kind of evidence out here, but so far there’s nothing.”

Suddenly, Lucy grabbed his sleeve. “Wait—what’s that?”

She was pointing to a large, corrugated metal drainage tunnel that stuck out of the bank of the pond. A stream of dirty-looking water trickled out of it, carrying bits and pieces of trash along with it. One particularly large piece seemed to have caught Lucy’s eye. Spaulding couldn’t see it well from this distance, but it appeared to be a grayish-white stick.

“It’s just a piece of litter,” he said. But he pushed his way through the tangled shrubbery overhanging the bank to get a clearer view.

Suddenly, the soft bank gave way beneath him. His foot plunged down and splashed into the pond. He managed to cling to a few skinny branches to keep himself from falling all the way in, but he still ended up with both feet ankle-deep in scummy water. On the bright side, he got a good close look at the stick—and then kind of wished he hadn’t.