![]()

![]()

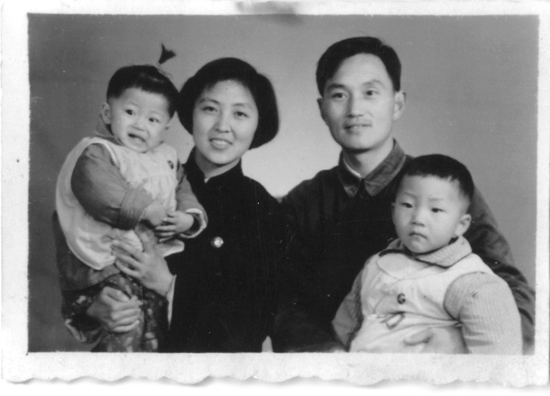

The year was 1966,

I was told,

five o’clock on a late spring afternoon.

Mama had been in labor for eight hours.

Baba was pacing up and down in the hall,

having just come from

a mass political meeting in the city square.

The doctor held me up in the air;

I was a ten-pound girl,

screaming loud with a little red face.

Outside the world was changing,

a revolution was in the making for my country.

Darkening clouds gathering in the sky above,

smothering thunders rolling on the horizon afar.

Mama sat on Baba’s bike, holding me tight in her arms;

Baba peddled toward home against the cold night wind.

Mama’s face was as pale as paper;

she caught cold on the way home,

during the weakest time after her labor.

Little Green—Xiao Qing—

was the name they gave me.

Qing, the green

of tree leaves in early spring,

of clear water in a deep pond,

my baba said;

of beautiful youth,

the evergreen of life,

my mama said;

and of precious jade worn close to the heart,

my nainai said.

Mama still says, telling me the story,

luckily for the illness,

she escaped the first struggle meeting

in the school where she taught

just by a day.

The beginning of

the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution

was announced,

people waving red flags on the streets and

shouting loud the slogans on their red banners:

“Ten Thousand Years Chairman Mao!”

“Ten Thousand Years the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution!”

Chairman Mao called to the country,

“Let’s hold the large flags of

the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution and

completely expose the reactionary position

of those so-called ‘academic authorities.’ ”

The school where Mama taught was in the countryside,

but there was no escape even there.

It was declared to be “a revolutionary battlefield,”

like many other schools around the country.

The day before Mama went back,

in the school ceremony hall

the Red Guards stood on the stage,

the teachers were gathered around the stage,

and other students gathered around them.

The teachers picked

were denounced on the stage,

forced down on their knees and

beaten in front of the crowd.

They were asked to slap their own faces

while denouncing themselves aloud

until the Red Guards were satisfied.

The only child of our grandma and grandpa,

they called her Cheng-Feng,

which means “becoming a phoenix.”

“You have no idea what trouble this could be,”

Mama told me.

“Phoenix is too traditional for the revolution.”

Some said the old world needed to be destroyed

for the new world to come.

That’s the idea of the revolution

I was born into.

That summer

around the country—our Middle Kingdom—

so many people died,

I was told many years later.

Spring 1967

“The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution,”

Chairman Mao said,

“is a great revolution that will touch people’s souls.”

A year after the revolution started,

Liu Shao-Qi,

the other chairman of the country then,

besides Chairman Mao,

was “downed with” completely.

People used to call him respectfully

“Our comrade Liu Shao-Qi,”

but an uncle teacher used these words one day too late.

It was his turn to criticize

the denounced leader in a struggle meeting.

“Our comrade Liu Shao-Qi,” he started with.

Just as he realized the mistake

and turned pale,

his head was already forced down.

“Down with the counterrevolutionary!”

people shouted,

throwing their arms up in the air,

trembling at this new discovery.

The uncle teacher slapped his own face,

calling himself one who “deserves to die.”

He carried the label ever since I remembered.

A dream was the first thing I ever remembered.

Mama was holding me in her arms,

snakes hanging from a big hollow tree,

wolves and hyenas running on the ground.

Mama was standing among these things,

holding me tight in her arms.

1968

I have a brother two years older,

who I called Gege.

Mama told me that

until the year I was two years old

and Gege was four,

the three of us had lived and traveled

between our home in the city where Baba worked

and the country school where Mama taught.

The city, like everywhere in the country,

The streets were filled with roaming Red Guards,

struggle meetings were held in every work unit,

and counterrevolutionaries were “downed with” every day.

A time of unpredictable changes,

a city of unrest.

Chairman Mao called to the whole country:

“Go up to the mountains and go down to the country,

to receive reeducation from poor and lower-middle-class peasants.”

Baba was sent down from the city to labor

in a May Seventh Cadre School in the countryside.

We lost our home in the city.

My gege and I stayed with Mama

in the country school

after Baba was gone.