Our first decisive step out of . . . our normal mentality is an ascent into a higher Mind . . . capable of the formation of a multitude of aspects of knowledge, ways of action, forms and significances of becoming. . . . [Its] most characteristic movement is a mass ideation, a system of totality of truth-seeing at a single view; the relations of idea with idea, of truth with truth are not established by logic but pre-exist and emerge already self-seen in the integral whole.

—Sri Aurobindo, The Life Divine

Passengers Carter Phipps and Ellen Daly, please report to Gate 14. This is the last call for boarding American Airlines Flight 567 to Chicago.”

My wife and I hurtled through the Denver airport, rushing through a special line at security, hurriedly throwing laptops and assorted gear into plastic trays. Finally we were clear, and as we took off across the airport lounge, lunging past restaurants and newsstands, for a moment I felt like O. J. Simpson in those old Hertz commercials, leaping over shoeshine stands in a mad dash to make his flight. I had never been paged in an airport before, and I didn’t want to miss the flight—especially now that the entire airport was witness to our drama.

It was a hot summer day in the Mile-High City, and even amid our mad scramble for the plane, I was a happy man. Our tardiness was justified. Our lateness was worth the price. We had just spent several hours in the downtown loft of Ken Wilber, and let’s face it—it’s not every day that one gets to hang out with one of the great philosophers of our age. American Airlines could wait.

If you’re not familiar with the work of Wilber, don’t be concerned. He doesn’t have a high profile in contemporary culture, choosing to stay out of the limelight and the rough-and-tumble talk-show culture that is the usual path to fame for our public intellectuals. So you won’t see him talking to world leaders on CNN. You won’t see him schmoozing with politicians at Davos. You won’t see interviews with him on 60 Minutes, Frontline, or C-SPAN. You can be an educated, thoughtful, well-informed citizen of the Western world and never have heard his name. But make no mistake, Wilber is important. His work and ideas—he calls it “integral philosophy” but it could just as easily fall under the category of evolutionary philosophy—are quietly affecting the way hundreds of thousands of people think about the world they live in. Ever since publishing his first book, The Spectrum of Consciousness, in 1977, Wilber’s work has chipped away at the philosophical girders of our postmodern age, clearing out contradictions and confusion and articulating new models and maps of reality that may shape the contours of our future. If postmodernism can be defined, as Jean-François Lyotard famously put it, as “incredulity toward meta-narratives,” then Wilber’s work is a legitimate antidote. With books called A Brief History of Everything and A Theory of Everything, Wilber has sought to create the sort of Holy Grail of grand narratives, a vast philosophical framework that attempts to integrate all categories of human knowledge and the history of human cultural development. He attempts to bring together religion, art, morality, economics, psychology, and all of the major sciences under the umbrella of one theory, one meta-perspective. When Wilber uses the world “integral,” he really means it.

This was my second trip to his Denver apartment. Wilber, then in his mid-fifties, seemed remarkably fit and full of energy, though I knew the reality was more complicated. Years earlier, he had been exposed to toxic chemicals in a nasty spill near Lake Tahoe, resulting in an autoimmune disease that would occasionally flare up and knock him off his feet for a few days or weeks. Indeed, a couple of years after our visit, the disease would temporarily get the better of him, and a grand mal seizure sent him to the emergency room. He has made an impressive recovery, but while his mind is fully intact, his body presents a daily challenge.

With his tall, chiseled, bodybuilder figure, Wilber sure didn’t come across as a bookish intellectual, though there was no mistaking his cognitive gifts. Born in Nebraska and raised a self-described “Army brat” whose family moved around the country, he still has something of that Midwestern hospitableness about him, a warmth of soul that belies his critics’ complaints that he is an aloof character, coolly surveying the culture from his mile-high home. On the contrary, he was down-to-earth and engaging, and made both my wife and me feel like close colleagues despite the fact that this was only our second meeting. He does have a marked tendency to curse like a sailor, as if he wants to erase all notions that he’s an ivory-tower character.

Wilber’s work has taken up the fallen standard of philosophy, the one that reads “The Truth Shall Set You Free” and has wrestled with that great demon of the information age—the explosive proliferation of knowledge to the point of mental overload. Little by little, he has brought forth new, clarifying, and liberating perspectives to help us navigate this chaotic context.

Of course, in a contemporary milieu that has often celebrated feeling and intuition over critical discourse and conceptual illumination, Wilber has certainly earned himself some pointed resentment as well as praise. Moreover, his embrace of evolutionarily inspired notions of purpose and progress, and his placement of spirituality at the heart of his philosophical framework, has not endeared him to a skeptical Western intelligentsia. But even at the beginning of his career, he knew that his own philosophy would run counter to the dominant intellectual currents of the day:

One thing was very clear to me as I struggled with how best to proceed in an intellectual climate dedicated to deconstructing anything that crossed its path: I would have to back up and start at the beginning, and try to create a vocabulary for a more constructive philosophy. Beyond pluralistic relativism is universal integralism; I therefore sought to outline a philosophy of universal integralism.

Put differently, I sought a world philosophy. I sought an integral philosophy, one that would believably weave together the many pluralistic contexts of science, morals, aesthetics, Eastern as well as Western philosophy, and the world’s great wisdom traditions. Not on the level of details—that is finitely impossible; but on the level of orienting generalizations: a way to suggest that the world really is one, undivided, whole, and related to itself in every way: a holistic philosophy for a holistic Kosmos: a world philosophy, an integral philosophy.

Wilber is not the first to use the term “integral” in this way. That distinction might better be placed at the feet of Indian sage Sri Aurobindo, or Harvard sociologist Pitirim Sorokin, or perhaps Jean Gebser. Steve McIntosh suggests that they all began using it around the same time in the early twentieth century, unaware of one another’s work. Whatever the case, Gebser and Aurobindo have been quite influential on Wilber. Gebser, with his emphasis on the structures of consciousness and culture, helped elucidate the succession of evolutionary unfolding that we have explored in the previous chapters and that Wilber has made central to his philosophy. In other respects, Wilber’s body of work resembles Aurobindo’s philosophy of “Integral Yoga,” at least in its comprehensive evolutionary vision. Of course, Wilber is a philosopher, not a spiritual visionary, and his work incorporates many twentieth-century breakthroughs of which Aurobindo had little knowledge. In particular, Wilber made generous use of the tremendous progress in psychology over the last century, becoming one of the first philosophical voices to incorporate developmental psychology as well as depth psychology into an integral framework.

It would be an exercise in futility to attempt to convey Wilber’s full contribution in the narrow confines of a single chapter. Moreover, his work is always evolving rapidly, picking up new streams of knowledge and integrating them into his overarching model, making any definitive statement soon outdated. But I do hope to show how his philosophy helps integrate many of the insights discussed in previous chapters, as well as organize their complexities and contradictions into a more easily comprehensible picture. In these brief pages, I will seek to convey why I believe there is no more powerful theoretical context than integral philosophy to help us understand what evolution actually means in the internal universe.

In this book, I’m calling this new worldview “evolutionary.” Wilber, as I’ve mentioned, prefers the term “integral.” Each name emphasizes a different dimension or aspect of this emerging stage of culture, but clearly there is enough overlap here to suggest that these terms are pointing at least in the same direction, if not more or less to the same idea. Is Wilber’s evolutionary system integral? Or is his integral system evolutionary? No doubt both are true. Integral practitioner and author Terry Patten describes integral philosophy as “meta-systemic.” It connects the dots, he explains, “and when you connect the dots, the single essential story that emerges out of the otherwise bewildering complexity of our world is evolution—the amazing multidimensional story of our universe’s gradually accelerating development—at first cosmic, then biological, then cultural and noetic.” Integral, evolutionary, or both, Wilber’s novel perspectives on the development of “self, culture, and nature” are seminal for anyone seeking to find their way forward in a postmodern world.

ONE REALITY, FOUR PERSPECTIVES

In the early 1990s, Wilber sat down to write his most comprehensive philosophical work yet, Sex, Ecology, Spirituality. It was his first attempt to fashion what could legitimately be called “a theory of everything.” It took him three years, and during this extended writing retreat, he ran up against a major problem. The problem was serious but simple—everybody had a different sequence of stages in their developmental system. We’ve looked at just a couple of such sequences in the preceding chapters, but Wilber was looking at hundreds, in multiple fields of knowledge.

Every school of thought, every system of knowledge, every field of study seemed to have a different set of assumptions as to what constituted the hierarchies of the natural world and of human culture. “There were linguistic hierarchies, contextual hierarchies, spiritual hierarchies,” Wilber writes in the introduction to his Collected Works (a ten-volume set of impressively weighty books, published in 2000). “There were stages of development in phonetics, stellar systems, cultural worldviews, autopoietic systems, technological modes, economic structures, phylogenetic unfoldings, superconscious realizations. . . . And they simply refused to agree with each other.”

As the days and months went by, Wilber sought to bring order to these multiple systems of knowledge. Working alone, in the days before Google allowed instant access to information, he read and read and read. And as he read, he began to make lists of all the various hierarchies that made up the particular structure of any given system of thinking. Those lists eventually begin to collect like stray pieces of clothing all over the floor of his house, a messy collection of data begging for order and clarity, an outward manifestation of a very contemporary conundrum—too much knowledge, too little context. Wilber describes the scene:

At one point, I had over two hundred hierarchies written out on legal pads lying all over the floor, trying to figure out how to fit them together. There were the “natural science” hierarchies, which were the easy ones, since everybody agreed with them: atoms to molecules to cells to organisms, for example. They were easy to understand because they were so graphic: organisms actually contain cells, which actually contain molecules, which actually contain atoms. . . .

The other fairly easy series of hierarchies were those discovered by the developmental psychologists. They all told variations on the cognitive hierarchy that goes from sensation to perception to impulse to image to symbol to concept to rule. The names varied, and the schemes were slightly different, but the hierarchical story was the same—each succeeding stage incorporated its predecessors and then added some new capacity. This seemed very similar to the natural science hierarchies, except they still did not match up in any obvious way. Moreover, you can actually see organisms and cells in the empirical world, but you can’t see interior states of consciousness in the same way. It is not at all obvious how these hierarchies would—or even could—be related.

Archimedes had his moment in the bathtub when he discovered the theory of water displacement; Newton had his legendary moment with the apple; Einstein had what he called the “happiest thought of my life,” an insight that led to relativity theory. The genesis of Wilber’s own breakthrough insight didn’t involve such sudden illumination. In fact, it was more grit than grace (to paraphrase the title of another of his many books). But while Wilber’s own epiphany may have lacked the “flash of insight” of those other great moments in the history of human knowledge, don’t be surprised if, when the dust clears and we can look back with the dispassionate lens of history, his signature insight compares favorably. Little by little, as he put the pieces together, the answer finally fell into place.

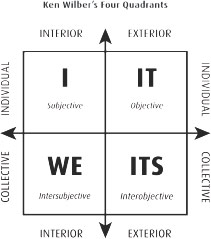

The answer was called “the four quadrants” and it became the basis for Wilber’s integral theory and evolutionary philosophy. He realized that all the many hierarchies and systems of knowledge could actually be divided up into four major categories. Some of the hierarchies were referring to collectives, some to individuals. Some were referring to exterior realities, some to interior realities. In fact, it seemed that every hierarchy on his list was referring either to an individual or a collective, and either to interior (subjective) or exterior (objective) dimensions of reality. It all fell together as the various schools and systems separated out into their respective quadrant, and soon he had a clear map—one that contextualized and embraced all of these seemingly conflicting schools of knowledge, one that transcended and yet included the cacophony of completing theories and settled them down into an integrated unity. He had started with a complex, confusing amalgamation of fragmented and isolated data from hundreds of disparate knowledge systems, and he had ended up with one relatively simple, coherent map of the cosmos (or Kosmos, the term he prefers).8

For Wilber, every event in the manifest world can be viewed from any one of those four perspectives: individual interior (I), collective interior (we), individual exterior (it), and collective exterior (its).

Let’s take me as an example. I have an individual, interior perspective—my thoughts, psychology, and spiritual experiences would fall under that category in Wilber’s upper-left quadrant. I also have an interior collective dimension, the culture I share with others, including worldviews, values, and belief systems. This is the “we” dimension, the intersubjective domain, which corresponds to the lower-left quadrant. Then I have an exterior, physical dimension—my brain, body, and nervous system, as well as the objective ways I behave in the world—this is the upper-right quadrant. And I participate in collective exterior systems—economic systems, political systems, social arrangements, and so forth, which fall into the lower-right quadrant. And here’s the key. Evolution, according to Wilber, happens in all four quadrants.

Let’s take an example from the biological world: the explosion in hominid brain size that happened over the last several million years. This evolution of the neocortex, according to this map, would not be confined to one quadrant. The physical brain doesn’t evolve on its own. So there would be a corresponding evolution in the left quadrants as well, an increase in our favorite hominid’s consciousness and capacities (upper-left), and a corresponding change in the culture that he or she was now able to share with others (lower-left). In the lower-right quadrant we would see an evolution in the sociopolitical systems that this hominid shares with others—from primitive tribal arrangements to global economics and trade, for example. In truth, it’s a more sophisticated version of the point that so many evolutionists have made—evolution of the interior corresponds to the evolution of the exterior; the evolution of the subjective corresponds to the evolution of the objective; the evolution of complexity corresponds to the evolution of consciousness. Only now we don’t have two perspectives from which to examine this process; we have four.

Let’s use a more mundane example. Imagine that I go through a religious awakening. I’m born again. I go from being a no-good, petty street criminal to a God-fearing, upstanding Christian. I find Jesus and my life is forever transformed. That’s a notable evolution in the self, and it will be reflected in each of these four quadrants. How?

First, that religious awakening is a massive shift in consciousness, and my interior world will be transformed. That evolution will mean that my worldview will shift and it will tend to put an upward pressure on the relationships I share with others. I’ll be less likely to hang out with drug dealers and more likely to form a “we” space with those who share my new worldview. The cultural reference points and quality of my personal relationships will be affected, hopefully for the better. Then, in the right-hand quadrants, we would see changes as well. The religious awakening will have effects not just on my consciousness but on my physical brain. New pathways will be created as my behavior shifts and the structure of my gray matter shifts along with it. Researchers talk about “God centers” in the brain. Perhaps I will connect with those aspects of brain chemistry as well. Whatever the case, things will change between my ears, both physically and mentally.

Finally, there is the lower-right, the “its” dimension of evolution. How will that be affected by my religious conversion? Well, imagine the society that is created in the ghettos of the inner city as a result of a poverty-ridden, disadvantaged criminal underclass. That creates its own social system, its own economic system, its own power structures and political order. And they are generally not healthy. But the religious awakening changes that—I begin to participate in and support the creation of new and different social systems, economic ventures, and power structures. My transformation starts to exert an upward, positive pressure on the lower-right structures of my chosen neighborhood. As the internal culture I share with others evolves, so do the external social systems I participate in. As always, my evolution is not mine alone; I’m affecting those around me. We are all, always, participating in all four quadrants of reality.

We could have long discussions about which quadrant “leads” the evolutionary process. For Marx, economic structures (lower-right) were the key to cultural evolution. Everything else was “superstructure,” meaning that it was sort of a secondary result of changes in economic conditions. For some, consciousness is primary. It all comes down to individuals’ shifts in personal consciousness (upper-left). To change the world, they would say, we must first change ourselves and everything will follow from that. But whatever our particular preference, what is perhaps more important is to see how these four quadrants represent a sort of web of connection, a matrix of interconnected structures. Push upward on any one of the quadrants, and the whole dynamic matrix begins to shift. Change in any one area puts positive evolutionary pressure on the other quadrants as well.

Unfortunately, many schools of thought that emphasize one particular quadrant don’t even recognize the existence of other schools of thought, and so we get what Wilber likes to call “quadrant absolutism”—people who think their particular corner of reality is the way, the truth, and the light. We see this with certain schools of scientific reductionism—they claim that just about everything can be reduced to the upper-right quadrant. They collapse all the rich realities of the upper-left interiors—thoughts, emotions, psychological structures, spiritual experiences, and so on—into the upper-right (“It’s all just brain chemistry”). Or with schools of Marxism, everything is reduced to economic structures, the lower-right quadrant. And we also see it with schools of mysticism or idealism, which claim that everything can be reduced to consciousness, the upper-left quadrant. We see it with philosophies that hold that all behavior can be reduced to deep social and cultural influences, the lower-left quadrant. This basic insight has been a guiding light for Wilber’s work—that most schools of thought are neither right nor wrong but rather “true but partial,” meaning they are right in their own limited corner of the universe but fail to take into account the larger ocean of ideas in which they swim. Thus, even in being right, they can be horribly blind. Even in being true, they can be partial. “The real intent of my writing is not to say, You must think in this way.” Wilber explains, “My work is an attempt to make room in the Kosmos for all of the dimensions, levels, domains, waves, memes, modes, individuals, cultures, and so on ad infinitum. I have one major rule: Everybody is right. More specifically, everybody—including me—has some important pieces of truth. . . . But every approach, I honestly believe, is essentially true but partial, true but partial, true but partial. And on my own tombstone, I dearly hope that someday they will write: He was true but partial.”

The four quadrants were instrumental in helping Wilber make sense out of the mess on his floor and the knowledge in his mind. And while they have remarkable breadth, they also have another important dimension: depth. Wilber has been one of the most prominent advocates of the core idea we have been exploring in this section, that individual and collective evolution progress through a series of discernible stages of consciousness and culture. And he is perhaps the first to notice just how much common ground there is among theorists and researchers from vastly different fields—from the social evolution stages of Habermas to the psychological stages of Baldwin to the cognitive stages of Piaget to the moral stages of Kohlberg and Gilligan to the cultural stages of Gebser to the sociological stages of Paul Ray, the ego-development stages of Loevinger and Susanne Cook-Greuter, the media theory stages of Marshall McLuhan, the spiritual stages of Sri Aurobindo, the color-coded cultural stages of Spiral Dynamics, and many, many more.

Gathering together all of these various systems under one roof, it became clear to Wilber that while each of these developmental, evolutionary theories is tracking different specifics, there is a clear evolutionary pattern at work. We are not looking at hundreds of different systems of development, all disparate and disconnected. Despite their varying disciplines, contexts, and fields, they have a remarkable amount in common. In fact, Wilber noticed, they display a consistent series of seven or eight clear and distinct worldviews, waves, levels, or stages, viewed from a number of different perspectives.

He began to call his map “AQAL”—all quadrants, all levels. Only by embracing all of these truths, only by acknowledging all of these important facets of reality, Wilber came to believe, could we even start to have a reasonable, non-distorted discussion about human knowledge, human culture, and how to address the many problems of our world. For Wilber, this is the test of any perspective in an integrally informed, evolutionary age: Does it include an awareness of all quadrants, all levels of reality—at least all of those we have collectively explored thus far in the human journey? And while Wilber has never shied away from the hierarchy that such a schema implies, he also recognizes, along with Gebser, Graves, and most sophisticated developmental theorists, that as we progress upward along the path of evolution, we must be careful not to draw facile moral conclusions about what it all means. He writes:

[T]his does not mean that development is nothing but sweetness and light, a series of wonderful promotions on a linear ladder of progress. For each stage of development brings not only new capacities but the possibility of new disasters; not just novel potentials but novel pathologies; new strengths, new diseases. In evolution at large, new emergent systems always face new problems: dogs get cancer, atoms don’t. Annoyingly, there is a price to be paid for each increase in consciousness, and this “dialectic of progress” (good news, bad news) needs always to be remembered. Still, the point for now is that each unfolding wave of consciousness brings at least the possibility for a greater expanse of care, compassion, justice, and mercy, on the way to an integral embrace.

“In every work of genius,” wrote Emerson, “we recognize our own rejected thoughts; they come back to us with a certain alienated majesty.” Wilber’s work is no exception. His theory has that unique trait of explaining the world in a way that seems completely novel yet somehow familiar at the same time. Once you deeply internalize the power of this simple map of reality, it lodges in your mind like a mental filtering mechanism, a natural organizing principle that begins to clarify and contextualize incoming data almost before thought. Any attempt to reduce the evolutionary process to one dimension of that four-part map begins to feel like a dangerous form of fundamentalism—not religious, perhaps, but limited and problematic nevertheless—a distortion of reality that inevitably leads to all sorts of conundrums and confusions, the disastrous result of which we see splashed across the headlines every day of the year.

A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON EVOLUTION

“The course of evolution has, just on this planet, gone from dirt to the sonnets of William Shakespeare. How can anyone not see meaning in that?” Wilber exclaimed to Ellen and me in his apartment that day in Denver, his voice rising as he delivered a mini-discourse on the current state of evolutionary theory. “How does one miss these extraordinary higher stages of unfolding? How could one look at dirt on the one hand and the music of Bach on the other and say, ‘Oh, they’re both equally meaningless phenomena.’ What kind of person could come up with that conclusion?”

Wilber is indeed passionate about the meaningful nature of evolution and has devoted a significant part of his philosophical work to understanding exactly how evolution works in the deeper dimensions of self, culture, and nature. As I have mentioned before in this book, most Evolutionaries see the nature of evolution through a particular lens, reflecting their particular angle on the deeper dimensions of reality. Some talk about the evolution of genes, some the evolution of cooperation, some the evolution of consciousness, some the evolution of information, some the evolution of values, some the evolution of economics, some the evolution of empathy, and so on. While these approaches can be complementary, they nevertheless each reflect the fundamental viewpoint of their proponents. In this sense, Wilber’s evolutionary vision is no different. While he is attempting to integrate many of these various currents of thought into one framework, he also privileges a very particular approach to the evolutionary process as being perhaps more true, more accurate, more foundational. So what is the unit of evolution that he sees as being the most essential element of this cosmic process? Perspectives.

Wilber tracks the evolutionary journey as a development of perspectives. His integral philosophy “replaces perceptions with perspectives,” as he puts it. It “re-defines the manifest realm as the realm of perspectives, not things nor events nor structures nor processes nor vasanas nor dharmas, nor archetypes, because all of these are perspectives before they are anything else, and they cannot be adopted or even stated without first assuming a perspective.”

It is a powerful and novel way to think about evolution. And it points to capacities we take for granted today that may not have always existed as potentials in consciousness. For Wilber, each evolutionary step in culture, each new wave of consciousness, each new worldview—from tribal to traditional to modern to postmodern, or from egocentric to ethnocentric to worldcentric—is also a fundamentally new perspective, a new vantage point from which to see the world.

To illustrate this, I like to think of the iconic picture of the Earth from space. That picture, in all its many forms, has helped to give us an amazing new perspective on the life of our planetary system. Beyond its aesthetic beauty, that picture represents something important, a sense of unity perhaps, an awareness of the system of which we all are a part, of our common home and the fate we share on this remarkable blue-green planet. It almost represents a new capacity in consciousness, the ability to embody the perspective, in some rudimentary way, of the planet itself. We can look at things from the perspective of how they influence, benefit, affect, or harm the overall integrated planetary system and all of its inhabitants. We can step beyond our personal perspective or the perspective of any particular species and grasp, at least temporarily, a critical viewpoint that has nothing to do with our everyday concerns. Not everyone alive today is able or willing to take such a perspective. In fact, it is still a rare capacity, and during other times of human history it simply was not possible to think about life in that manner. Such a planetary perspective was probably not even available to human consciousness, except perhaps through some remarkable individual cognitive leap. That is not to denigrate our ancestors. Rather it is to point out that we perpetually underappreciate our evolutionary achievements. And a big one of those achievements is the capacity to embody more encompassing, more comprehensive, and more integrated perspectives.

There is another, perhaps more humbling, implication of this “ontology of perspectives.” It also means that we are already always embedded within a perspective. In the actual interior world of my own consciousness, I am not just a subject apprehending other objects in consciousness. I, the subject, am also embedded in very real perspectives that often remain unseen by the interior vision of my mind’s eye. In other words, I may think that I have some objective relationship to the events in my perception, that I am seeing reality “as it is,” but that is a trick, an illusion of first-person consciousness. My awareness is always conditioned by a perspective. It is an insight that runs counter to a fundamental assumption of the meditative and contemplative traditions—that knowledge gained through introspection is trustworthy. Wilber points out that postmodern thinkers such as French philosopher Michel Foucault accurately noticed that this was a fallacy endemic to introspective traditions. We are always embedded in intersubjective cultural structures that influence our “objective” perception of reality. For example, if a Christian monk has a vision of Jesus, he may believe that he is seeing an objective spiritual reality. But he fails to recognize, these thinkers tell us, that his vision—even if it is spiritually authentic—is inevitably being influenced by tremendous cultural and social conditioning that is all taking place prior to and outside of the monk’s immediate awareness. Like a Hindu witnessing a vision of Krishna, or Tibetan experiencing a powerful visitation from a bodhisattva, he is mistaking a cultural archetype for objective perception.

In the preceding chapters, we explored how unseen intersubjective worldviews and structures of consciousness condition our awareness more than most people realize. Many of us are unwitting mouthpieces of subtle but incredibly influential worldviews—whether we like it or not, whether we think we are or not. We may think that we perceive reality as it is, but in fact we are each more like the protagonist in our own personal version of The Truman Show, and we cannot see the subtler cultural forces that are invisibly shaping all of our perceptions—even our most cherished spiritual experiences.

So what’s the good news? The good news is that even our capacity to understand this truth shows evolution at work. We are gaining the capacity to take more and more broad, encompassing, sophisticated, and subtle perspectives. Look how far we’ve come in the last fifty thousand years. Once upon a time, we could likely do little but appreciate and apprehend our own vital experience, but slowly we developed unprecedented new perspectives. Take, for example, the capacity to “step outside of ourselves” and think about our own experience with some greater measure of objectivity. That’s an extraordinary leap forward in evolutionary terms. More recently, we’ve developed methods for exploring the natural world with the tools of science. That too is a perspective—one that has disembedded itself from the natural world enough to begin to analyze it. This capacity was not always part of the human experience but rather was the hard-won result of the evolution of perspectives over time.

Eventually we developed the capacity to stand in another person’s shoes, to imagine, through an extraordinary leap of consciousness, what it might be like to feel their emotions, to understand their suffering, to appreciate their joys and sorrows, even in circumstances vastly different from our own. This is yet another great gift of evolution, and one that not every individual on the planet has actually developed. And evolution continues. We are developing ever more subtle perspectives—for example, the capacity to take the perspective of the species itself, to imagine what might be good or bad for the future of humanity as a whole. We have even developed the capacity to take the perspectives of other species, to begin to imagine the quality of their consciousness and adapt our human activities to start to take into account their existence. And now, in just the last few decades, we are beginning to develop, as we have seen in this book, the extraordinary capacity to take the perspective of evolution itself, to step inside the mind of the process, so to speak, and explore reality from that very remarkable and revelatory perspective. This has just happened—in an evolutionary blink of an eye. So don’t underestimate the power of perspectives and the effect of their evolution on every last dimension of our lives.

THE KOSMIC GROOVES OF EVOLUTION

Thinking about Ken Wilber put me in mind of another underappreciated American philosopher. Charles Sanders Peirce was celebrated by his contemporary William James, praised as the greatest philosopher in America by Bertrand Russell, declared the American Aristotle by Alfred North Whitehead, and respected by countless other intellectuals of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Yet his legacy is relatively obscure, and he is barely recognized for his contributions to evolutionary thought. Like Wilber today, he was, in his own time, one of the most important thinkers the average educated American citizen had never heard of. And when it came to evolution, his philosophy was equally innovative. In fact, Peirce set in motion a way of thinking about the subject that would, more than a century later, inspire one of the aspects of Wilber’s work that I find most useful to understanding an evolutionary worldview.

Peirce lived a strange and in some respects tragic life. Born the son of a Harvard professor in 1839, he was a successful student, but history tells us that his interpersonal skills—his emotional intelligence, we might say—didn’t quite match his IQ. He seemed to suffer from a difficult personality (some of which stemmed from a physical condition) that earned him many powerful enemies and complicated his efforts to obtain academic respectability and credibility. But whatever his physical and psychological limitations, his mind lived on another plane, and his voluminous writings (mostly unpublished in his lifetime), his eclectic brilliance, and his groundbreaking thought were many decades ahead of their time. Though Whitehead only became aware of Peirce’s work more than a decade after the philosopher’s death, he recognized in this evolutionarily inspired pioneer a kindred spirit and saw important similarities to his own work. Like Whitehead, Peirce was at the forefront of a change in the way we understand the universe, seeing evolution, movement, and process where others saw only fixed laws, dead matter, and eternal stasis.

I found it remarkable to discover, in the course of my research, that all the way back in the nineteenth century Peirce was questioning the spell of solidity even as it applied to the most sacred cows of the physical sciences: the laws of nature. For Peirce, the entire universe and all of its forces and creations were subject to evolution. Indeed, Peirce’s work was one of the first to begin to theorize how something as ostensibly absolute as a law might be created through the processes of evolution. Perhaps the laws of nature are not unchanging, applying to everything for all time, he suggested. Perhaps they didn’t pre-date the universe. Perhaps they, too, evolved along with the forms and structures of our cosmos.

Peirce suspected that many of the seemingly fixed structures of our universe are in fact better described as habits—habits that have become so deeply embedded in nature that they behave like laws, fixed and unchangeable. In 1915, the Mid-West Quarterly, a publication of the University of Nebraska, published the following description of Peirce’s ideas as presented in his lectures at Johns Hopkins University.

May not the laws of the universe be the acquired habits of the universe? May there not still be a possibility of the modification of these habits? May there not be the possibility, forever, of the formation of new habits, new laws? May not law be evolved from a primordial chaos, a universe of chance? In the play of chance still apparent may we not see the continual renewal of the life of the universe, a continual renewal of the capacity for habit forming and growth?

Peirce suggested all of this before science had any sense of cosmological evolution, of the deep-time developmental history of our universe. Questions concerning the laws of physics are even more fascinating today, particularly in the context of our current understanding of Big Bang Theory. Did those laws exist in some timeless void prior to the initial cosmic emergence? Did they pop into existence at the moment of that great conflagration? Were they gifts, perhaps, of a previous universe, a sort of cosmically inherited informational DNA designed to help structure the evolution of our own realm of time and space? When it comes to such issues that get at the heart of our cosmic origins, we still have far more questions than answers.

Biologist Rupert Sheldrake is another thinker who has suggested that the laws of nature may not be immutable and eternal but are more like habits. And he points out that most physicists have not thought deeply about these questions in light of our new cosmology. “Although cosmology is now evolutionary,” he writes, “old habits of thought die hard. Most scientists take eternal laws of Nature for granted—not because they have thought about them in the context of the Big Bang, but because they haven’t.” Lately, it seems, a few more physicists have stepped into the breach with interesting speculations about the source of the laws of nature, such as Templeton Prize winner Paul Davies and science writer James Gardner. But wherever such speculations ultimately lead us, what is important for our discussion is that once again the spell of solidity is broken and we can at least begin to consider the possibility that certain characteristics of the universe that seem immutable and unchanging might better be considered as evolutionary—things that develop over time through habitual repetition until they become more and more established. Eventually, in a cognitive illusion that fools us again and again, they seem fixed, eternal and unchanging, when actually they are nothing of the sort. Again, my point is not to weigh in on questions of physics or make any claims about what happened in the far-off reaches of deep time but rather to illuminate a way to think about evolution that becomes particularly interesting when we apply it—as Wilber would do—to the internal universe.

But first, Sheldrake would attempt to apply it to biology, with a theory he called morphic resonance. In 1981, he published A New Science of Life, suggesting that a new kind of information field, a “Morphogenetic” or “morphic” field, may be critical in helping to determine the forms and structures of living systems. A morphic field is a place where information is stored, where the informational memory or “habits” of past forms and structures reside and influence the form and content of the present. “According to this hypothesis,” Sheldrake writes, “systems are organized the way they are because similar systems were organized that way in the past. For example, the molecules of a complex organic chemical crystallize in a characteristic pattern because the same substance crystallized that way before; a plant takes up the form characteristic of its species because past members of its species took up that form; and an animal acts instinctively in a particular manner because similar animals behaved like that previously.”

We can see a very nonesoteric version of this “repetition creates habit” idea in the remarkable plasticity of the brain. Our contemporary appreciation of neuroscience tells us that when we act in a novel way, we are creating new connections in our brains that support that particular new behavior. Repeat the behavior and the neural connections are strengthened. Each time we act or think in that particular way, the neural pathways become a little more established. The habit is slowly forming. We are developing new pathways in the brain, new habits of mind, which in turn correspond to new ways of thinking and living. Obviously, there are constraints on how much the brain can change, but the basic point stands: novel behaviors create new pathways that develop into habits, and perhaps eventually into instincts.

In the 1980s Sheldrake’s proposals were summarily dismissed by the scientific powers that be and his book was referred to as the “best candidate for burning there has been in many years” by one of the more respectable scientific journals. This is in part because there is no place in existing biological theory for nonphysical, or very subtle, information fields that influence the development of biological form (though, as Sheldrake points out, the field of physics is much more open to such possibilities). He has recently republished the original book with updated data and has proposed a number of testable experiments to support his ideas and carried them out with mixed results. He has won some converts but has done little to convince skeptics.

Whatever the scientific fate of the idea in physics or biology, once again, the evolutionary principle is important—as Wilber has recognized. He has suggested that Sheldrake’s morphic fields are similar to deep structures of consciousness in the internal universe. Thus, the stages of development that we have discussed in previous chapters become, from this perspective, psychological, social, and cultural “grooves,” as Wilber likes to call them—“Kosmic habits” that have developed in the noosphere. Citing the common observation that once a certain task, such as synthesizing complex molecules, or rats learning a particular maze, has been accomplished in one part of the world, it can more easily be accomplished somewhere else, Wilber draws a parallel to the emergence of psychological forms: “In historical unfolding, once . . . [a stage of development] had significantly emerged anywhere in the world, it began more easily appearing elsewhere around the world. A difficult, novel, creative emergence had settled into a Kosmic habit.”

To illustrate Wilber’s point, I like to imagine I am walking into an unexplored land. In order to get from point A to point B, I must choose a particular route. In my wake, I leave a path, but a barely distinguishable one, only a slight imprint of my footsteps that a subsequent traveler might notice. Indeed, the second traveler may or may not see that trail I followed, but we might say that there is a slightly increased chance that he or she will be drawn to travel along the same pathway. With each subsequent traveler, that likelihood increases; as the path gets more well worn, the memory gets more stable, the groove in the land cuts deeper. Eventually, after millions of individuals have passed that way, the trail, now a well-established pathway, acts as a powerful attractor to any traveler on the same route. It would seem almost nonsensical not to follow it. One may add slight features to the existing path, but when it comes to the basic trail, the structure is relatively stable and mostly unchanging, a strong mold set into the internal universe. In fact, it might seem as if it were a permanent “unyielding mold” that has always been there. Such is the nature of deep Kosmic grooves. We may not be able to see them the way we can see a trail in the ground, but they are carved deep into our consciousness nonetheless, and they exercise the same power of attraction over us. And the older the pathway, the older the structure, the more settled and determined it is.

Perhaps the best part of this perspective is that it explains the endurance of the past and its influence on the present, but like all good developmental theories these days, it is also upwardly open, allowing for the development of new habits and evolutionary grooves as humans evolve forward in history and confront new challenges.

Most of the early stages of [human] development have been around for thousands of years. And billions of human beings have gone through them so that now they are automatically part of development. They’re as rutted as the Grand Canyon. . . . But new stages . . . might be a yard or two deep, that’s all that’s been cut yet. And so, boy, it’s hard to make things stick in that. And anybody who’s pushing into those stages is basically going out next to the Grand Canyon, taking a stick, and starting to dig another groove. . . .”

Wilber further explains:

This does not mean that individuals cannot pioneer into these higher potentials . . . only that those structures are as yet lightly formed, consisting only of the faint footprints and gossamer trails of highly evolved souls who have pushed ahead, leaving gentle whispers of the extraordinary sights that lie before us if we have the courage to grow. These are higher potentials and nonordinary states, but . . . they have not yet become structures settled into stable Kosmic habits.

Let’s take, for example, the evolutionary worldview that this book is endeavoring to elucidate. At this point it remains unformed, a fascinating mixture of new ideas and like-minded little memes and values, all connected to larger breakthroughs in our understanding of evolution. To pick up on my earlier image, it’s multiple sets of footprints, all heading in roughly the same direction, crossing over one another, sometimes rambling, not yet a clear trail but a compelling imprint. Wilber refers to this time as the “frothy, chaotic, wildly creative leading-edge of consciousness unfolding and evolution, still rough and ready in its newly settling contours, still far from settled habit.” And he makes a critical point: “This is why today, right now, we want to try to lay down as ‘healthy’ a . . . groove as we possibly can, because we are creating morphic fields in all subsequent Kosmic memory.”

This brings to light another important implication of the notion of Kosmic karma or evolutionary grooves—it points to a new kind of moral imperative. As we begin to recognize ourselves as participants in the creative process, we also realize that there are ethical implications to this perspective. What we do matters—not just for its effect on the present but for its effect on the as-yet-unformed future. We are not just participating in an already-created universe; we are also participants in the process of creation. And that knowledge carries tremendous moral weight. It comes with a very real ethical context, Wilber suggests—one based not on some decree from an all-knowing God or religious belief system but on our emerging understanding of the way in which evolution works and the role we play in that process. Are you ready to be the individual who walks out on that virgin land and takes responsibility for laying down a positive trail? Are you willing to be the person whose behavior, good or bad, positive or negative, evolutionary or deevolutionary, could ratchet into the fabric of the universe a new habit, a new groove, one that may very well influence others? In EnlightenNext magazine, Wilber pointed out:

Paul Tillich said that what we call the Renaissance was participated in by about a thousand people. And that is astonishing. About a thousand people defined an entire culture by the choices they made at the leading edge and because they were choosing from the highest stage of development at that point, they were laying down structures that became the future of humanity in the Enlightenment, and then in modernity and then in post modernity. A thousand people. And the same thing can happen today if you are awakened to the leading edge . . . you very well could be part of the next thousand people that are laying down the form of tomorrow. . . . And we’re doing this now as a conscious process.

Now, before I start planting seeds of grandiosity, let’s understand that it is not every day that Joe Normal is going to be walking around defining new grooves in the internal universe. Most of us live out our entire lives in the well-worn grooves of yesteryear. Nevertheless, the basic point stands. Wilber calls this emerging moral sense the “evolutionary imperative,” reminiscent of Immanuel Kant’s categorical imperative. Kant was famous for his suggestion that each person should behave as if his actions would become a universal rule. We can see in his categorical imperative the dawning of a powerful world-centric morality, a sense of the universality of our ethical concerns. Human beings in his day were just beginning to think about morality in a new way, breaking out of the smaller ethical context of tribes, nations, or religious faiths, and starting to consider the moral truths that concern humanity as a whole. And Kant was leading the charge. Two and a half centuries later, the idea is reemerging, only this time it is not a world-centric morality we are talking about, it is a Kosmos-centric, evolutionary morality that is now the leading edge of our own discussions of how to redefine right and wrong in a postmodern culture that is none too crazy about either of those notions. Like almost everything else in an evolutionary universe, morality evolves. And with this new imperative, Evolutionaries find themselves embedded once again in a powerfully ethical context, connected to the newly discovered truths of an evolutionary universe, awake to the deep interior consequences of our actions, and consciously responsible for the choices we make at the edges of the future—where novel habits form, and new trails, lightly traveled, may slowly become the accepted pathways for tomorrow’s culture.