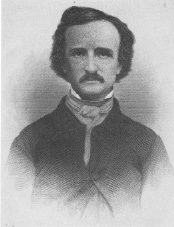

Obituary

Philadelphia Quaker City

The Late M Edgar Allan Poe

October 20, 1849

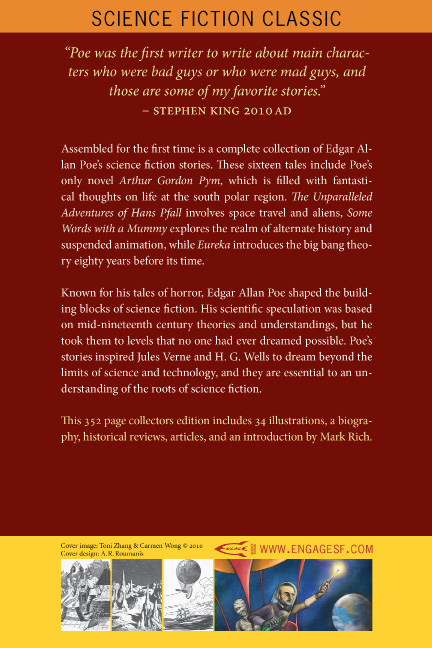

“Edgar Allan Poe died, in the city of Baltimore, on Sunday, nearly two weeks ago. He is dead and we are conscious that words are fruitless to express our feelings in relation to his death. Only a few weeks ago we took him by the hand in our office, and heard him express himself in these words – “I am sick – sick at heart. I have come to see you before I leave for Virginia. I am homesick for Virginia. I don’t know why it is but when my foot is once in Virginia, I feel myself a new man. It is a pleasure to me to go into her woods – to lay myself upon her sod – even to breathe her air.” These words, the manner in which they were spoken, made a deep impression. They were the words of a man of genius, hunted by the world, trampled upon by the men whom he had loaded with favors, and disappointed on every turn of life. Poe spent a day with us. We talked of the time we had first met, in his quiet home on Seventh Street, Philadelphia, when it was made happy by the presence of his wife – a pure and beautiful woman. He talked also of his last book “Eureka,” well termed a “Prose Poem,” and spoke much of projects for the future. When we parted from him on the cars, he held our hand for a long time, and seemed loath to leave us – there was in his voice, look and manner something of a presentiment that his strange and stormy life was near its close. His looks and his words were vividly impressed upon our memory, until we heard of his death and the news of that event brought every look and word home to us as keenly as though only a moment had passed since we parted from him. We frankly confess that, on this occasion, we cannot imitate a number of editors who have taken upon themselves to speak of Poe, and his faults in a tone of condescending pity! That Poe had faults we do not deny. He was a harsh, a bitter and sometimes an unjust critic. But he was a man of genius – a man of high honor – a man of good heart. He was not an intemperate man. When he drank, the first drop maddened him; hence his occasional departures from the strict propriety. But he was not an habitual drinker. As an author his name will live, while three-fourths of the bastard critics and mongrel authors of the present day go down to nothingness and night. And the men who now spit upon his grave, by way of retaliation for some injury which they imagined they have received from Poe living, would do well to remember, that it is only an idiot or a coward who strikes the cold forehead of a corpse.

George Lippard

[1]Whaling vessels are usually fitted with iron oil-tanks – why the Grampus was not I have never been able to ascertain.

[2]The case of the brig Polly, of Boston, is one so much in point, and her fate, in many respects, so remarkably similar to our own, that I cannot forbear alluding to it here. This vessel, of one hundred and thirty tons burden, sailed from Boston, with a cargo of lumber and provisions, for Santa Croix, on the twelfth of December, 1811, under the command of Captain Casneau. There were eight souls on board besides the captain – the mate, four seamen, and the cook, together with a Mr. Hunt, and a negro girl belonging to him. On the fifteenth, having cleared the shoal of Georges, she sprung a leak in a gale of wind from the southeast, and was finally capsized; but, the masts going by the board, she afterward righted. They remained in this situation, without fire, and with very little provision, for the period of one hundred and ninety-one days (from December the fifteenth to June the twentieth), when Captain Casneau and Samuel Badger, the only survivors, were taken off the wreck by the Fame, of Hull, Captain Featherstone, bound home from Rio Janeiro. When picked up, they were in latitude 28 degrees N., longitude 13 degrees W., having drifted above two thousand miles! On the ninth of July the Fame fell in with the brig Dromero, Captain Perkins, who landed the two sufferers in Kennebeck. The narrative from which we gather these details ends in the following words:

“It is natural to inquire how they could float such a vast distance, upon the most frequented part of the Atlantic, and not be discovered all this time. They were passed by more than a dozen sail, one of which came so nigh them that they could distinctly see the people on deck and on the rigging looking at them; but, to the inexpressible disappointment of the starving and freezing men, they stifled the dictates of compassion, hoisted sail, and cruelly abandoned them to their fate.”

[3] Among the vessels which at various times have professed to meet with the Auroras may be mentioned the ship San Miguel, in 1769; the ship Aurora, in 1774; the brig Pearl, in 1779; and the ship Dolores, in 1790. They all agree in giving the mean latitude fifty-three degrees south.

[4] The terms morning and evening, which I have made use of to avoid confusion in my narrative, as far as possible, must not, of course, be taken in their ordinary sense. For a long time past we had had no night at all, the daylight being continual. The dates throughout are according to nautical time, and the bearing must be understood as per compass. I would also remark, in this place, that I cannot, in the first portion of what is here written, pretend to strict accuracy in respect to dates, or latitudes and longitudes, having kept no regular journal until after the period of which this first portion treats. In many instances I have relied altogether upon memory.

[5] This day was rendered remarkable by our observing in the south several huge wreaths of the grayish vapour I have spoken of.

[6] The marl was also black; indeed, we noticed no light colored substances of any kind upon the island.

[7] For obvious reasons I cannot pretend to strict accuracy in these dates. They are given principally with a view to perspicity of narrative, and as set down in my pencil memorandum.

– –