Time, Work-Discipline and Industrial CapitalismTime, Work-Discipline and Industrial Capitalism

We kept an old Servant whose name was Wright, in constant Work, though paid by the Week, he was a Wheel-wright by Trade. . . It happen’d one Morning that a Cart being Broken-down upon the Road. . . the old Man was fetch’d to repair it where it lay; while he was busy at his Work, comes by a Countryman that knew him, and salutes him with the usual Compliment, Good-Morrow Father Wright, God speed your Labour; the old Fellow looks up at him. . . and with a kind of pleasant Surlyness, answer’d, I don’t care whether he does or no, ’tis Day-Work.

D. Defoe, The Great Law of Subordination Considered; or the Insolence and Insufferable Behaviour of SERVANTS in England duly enquired into (1724)

To the upper Part of Mankind Time is an Enemy, and. . . their chief Labour is to kill it; whereas with the others, Time and Money are almost synonymous.

Henry Fielding, An Enquiry into the Causes of the late Increase of Robbers (1751)

Tess. . . started on her way up the dark and crooked lane or street not made for hasty progress; a street laid out before inches of land had value, and when one-handed clocks sufficiently subdivided the day.

Thomas Hardy

I

It is commonplace that the years between 1300 and 1650 saw within the intellectual culture of Western Europe important changes in the apprehension of time.11 In the Canterbury Tales the cock still figures in his immemorial role as nature’s timepiece: Chauntecleer —

Caste up his eyen to the brighte sonne,

That in the signe of Taurus hadde yronne

Twenty degrees and oon, and somwhat moore,

He knew by kynde, and by noon oother loore

That it was pryme, and crew with blisful stevene. . .

But although “By nature knew he ech ascensioun/Of the equynoxial in thilke toun”, the contrast between “nature’s” time and clock time is pointed in the image —

Wel sikerer was his crowyng in his logge

Than is a clokke, or an abbey orlogge.

This is a very early clock: Chaucer (unlike Chauntecleer) was a Londoner, and was aware of the times of Court, of urban organisation and of that “merchant’s time” which Jacques Le Goff, in a suggestive article in Annales, has opposed to the time of the medieval church.11

I do not wish to argue how far the change was due to the spread of clocks from the fourteenth century onwards, how far this was itself a symptom of a new Puritan discipline and bourgeois exactitude. However we see it, the change is certainly there. The clock steps on to the Elizabethan stage, turning Faustus’s last soliloquy into a dialogue with time: “the stars move still, time runs, the clock will strike”. Sidereal time, which has been present since literature began, has now moved at one step from the heavens into the home. Mortality and love are both felt to be more poignant as the “Snayly motion of the mooving hand”22 crosses the dial. When the watch is worn about the neck it lies in proximity to the less regular beating of the heart. The conventional Elizabethan images of time as a devourer, a defacer, a bloody tyrant, a scytheman, are old enough, but there is a new immediacy and insistence.11

As the seventeenth century moves on the image of clockwork extends, until, with Newton, it has engrossed the universe. And by the middle of the eighteenth century (if we are to trust Sterne) the clock had penetrated to more intimate levels. For Tristram Shandy’s father — “one of the most regular men in everything he did. . . that ever lived” — “had made it a rule for many years of his life, — on the first Sunday night of every month. . . to wind up a large house-clock, which we had standing on the back-stairs head”. “He had likewise gradually brought some other little family concernments to the same period”, and this enabled Tristram to date his conception very exactly. It also provoked The Clockmakers Outcry against the Author:

The directions I had for making several clocks for the country are countermanded; because no modest lady now dares to mention a word about winding-up a clock, without exposing herself to the sly leers and jokes of the family. . . Nay, the common expression of street-walkers is, “Sir, will you have your clock wound up?”

Virtuous matrons (the “clockmaker” complained) are consigning their clocks to lumber rooms as “exciting to acts of carnality”.22

However, this gross impressionism is unlikely to advance the present enquiry: how far, and in what ways, did this shift in time-sense affect labour discipline, and how far did it influence the inward apprehension of time of working people? If the transition to mature industrial society entailed a severe restructuring of working habits — new disciplines, new incentives, and a new human nature upon which these incentives could bite effectively — how far is this related to changes in the inward notation of time?

II

It is well known that among primitive peoples the measurement of time is commonly related to familiar processes in the cycle of work or of domestic chores. Evans-Pritchard has analysed the time-sense of the Nuer:

The daily timepiece is the cattle clock, the round of pastoral tasks, and the time of day and the passage of time through a day are to a Nuer primarily the succession of these tasks and their relation to one another.

Among the Nandi an occupational definition of time evolved covering not only each hour, but half hours of the day — at 5.30 in the morning the oxen have gone to the grazing-ground, at 6 the sheep have been unfastened, at 6.30 the sun has grown, at 7 it has become warm, at 7.30 the goats have gone to the grazing-ground. etc. — an uncommonly well-regulated economy. In a similar way terms evolve for the measurement of time intervals. In Madagascar time might be measured by “a rice-cooking” (about half an hour) or “the frying of a locust” (a moment). The Cross River natives were reported as saying “the man died in less than the time in which maize is not yet completely roasted” (less than fifteen minutes).11

It is not difficult to find examples of this nearer to us in cultural time. Thus in seventeenth-century Chile time was often measured in “credos”: an earthquake was described in 1647 as lasting for the period of two credos; while the cooking time of an egg could be judged by an Ave Maria said aloud. In Burma in recent times monks rose at daybreak “when there is light enough to see the veins in the hand”.11 The Oxford English Dictionary gives us English examples — “pater noster wyle”, “miserere whyle” (1450), and (in the New English Dictionary but not the Oxford English Dictionary) “pissing while” — a somewhat arbitrary measurement.

Pierre Bourdieu has explored more closely the attitudes towards time of the Kaabyle peasant (in Algeria) in recent years: “An attitude of submission and of nonchalant indifference to the passage of time which no one dreams of mastering, using up, or saving. . . Haste is seen as a lack of decorum combined with diabolical ambition”. The clock is sometimes known as “the devil’s mill”; there are no precise meal-times; “the notion of an exact appointment is unknown; they agree. only to meet ‘at the next market’”. A popular song runs:

It is useless to pursue the world, No one will ever overtake it.22

Synge, in his well-observed account of the Aran Islands, gives us a classic example:

While I am walking with Michael someone often comes to me to ask the time of day. Few of the people, however, are sufficiently used to modern time to understand in more than a vague way the convention of the hours and when I tell them what o’clock it is by my watch they are not satisfied, and ask how long is left them before the twilight.33

The general knowledge of time on the island depends, curiously enough, upon the direction of the wind. Nearly all the cottages are built. . . with two doors opposite each other, the more sheltered of which lies open all day to give light to the interior. If the wind is northerly the south door is opened, and the shadow of the door-post moving across the kitchen floor indicates the hour; as soon, however, as the wind changes to the south the other door is opened, and the people, who never think of putting up a primitive dial, are at a loss. . .

When the wind is from the north the old woman manages my meals with fair regularity; but on the other days she often makes my tea at three o’clock instead of six. . .11

Such a disregard for clock time could of course only be possible in a crofting and fishing community whose framework of marketing and administration is minimal, and in which the day’s tasks (which might vary from fishing to farming, building, mending of nets, thatching, making a cradle or a coffin) seem to disclose themselves, by the logic of need, before the crofter’s eyes.22 But his account will serve to emphasise the essential conditioning in differing notations of time provided by different work-situations and their relation to “natural” rhythms. Clearly hunters must employ certain hours of the night to set their snares. Fishing and seafaring people must integrate their lives with the tides. A petition from Sunderland in 1800 includes the words “considering that this is a seaport in which many people are obliged to be up at all hours of the night to attend the tides and their affairs upon the river”.33 The operative phrase is “attend the tides”: the patterning of social time in the seaport follows upon the rhythms of the sea; and this appears to be natural and comprehensible to fishermen or seamen: the compulsion is nature’s own.

In a similar way labour from dawn to dusk can appear to be “natural” in a farming community, especially in the harvest months: nature demands that the grain be harvested before the thunderstorms set in. And we may note similar “natural” work-rhythms which attend other rural or industrial occupations: sheep must be attended at lambing time and guarded from predators; cows must be milked; the charcoal fire must be attended and not burn away through the turfs (and the charcoal burners must sleep beside it); once iron is in the making, the furnaces must not be allowed to fail.

The notation of time which arises in such contexts has been described as task-orientation. It is perhaps the most effective orientation in peasant societies, and it remains important in village and domestic industries. It has by no means lost all relevance in rural parts of Britain today. Three points may be proposed about task-orientation. First, there is a sense in which it is more humanly comprehensible than timed labour. The peasant or labourer appears to attend upon what is an observed necessity. Second, a community in which task-orientation is common appears to show least demarcation between “work” and “life”. Social intercourse and labour are intermingled — the working day lengthens or contracts according to the task — and there is no great sense of conflict between labour and “passing the time of day”. Third, to men accustomed to labour timed by the clock, this attitude to labour appears to be wasteful and lacking in urgency.11

Such a clear distinction supposes, of course, the independent peasant or craftsman as referent. But the question of task-orientation becomes greatly more complex at the point where labour is employed. The entire family economy of the small farmer may be task-orientated; but within it there may be a division of labour, and allocation of roles, and the discipline of an employer-employed relationship between the farmer and his children. Even here time is beginning to become money, the employer’s money. As soon as actual hands are employed the shift from task-orientation to timed labour is marked. It is true that the timing of work can be done independently of any time-piece — and indeed precedes the diffusion of the clock. Still, in the mid seventeenth century substantial farmers calculated their expectations of employed labour (as did Henry Best) in “dayworks” — “the Cunnigarth, with its bottomes, is 4 large dayworkes for a good mower”, “the Spellowe is 4 indifferent dayworkes”, etc.;11 and what Best did for his own farm, Markham attempted to present in general form:

A man. . . may mow of Corn, as Barley and Oats, if it be thick, loggy and beaten down to the earth, making fair work, and not cutting off the heads of the ears, and leaving the straw still growing one acre and a half in a day: but if it be good thick and fair standing corn, then he may mow two acres, or two acres and a half in a day; but if the corn be short and thin, then he may mow three, and sometimes four Acres in a day, and not be overlaboured. . .22

The computation is difficult, and dependent upon many variables. Clearly, a straightforward time-measurement was more convenient.33

This measurement embodies a simple relationship. Those who are employed experience a distinction between their employer’s time and their “own” time. And the employer must use the time of his labour, and see it is not wasted: not the task but the value of time when reduced to money is dominant. Time is now currency: it is not passed but spent.

We may observe something of this contrast, in attitudes towards both time and work, in two passages from Stephen Duck’s poem, “The Thresher’s Labour”.11 The first describes a work-situation which we have come to regard as the norm in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries:

From the strong Planks our Crab-Tree Staves rebound,

And echoing Barns return the rattling Sound.

Now in the Air our knotty Weapons Fly;

And now with equal Force descend from high:

Down one, one up, so well they keep the Time,

The Cyclops Hammers could not truer chime. . .

In briny Streams our Sweat descends apace,

Drops from our Locks, or trickles down our Face.

No intermission in our Works we know;

The noisy Threshall must for ever go.

Their Master absent, others safely play;

The sleeping Threshall doth itself betray.

Nor yet the tedious Labour to beguile,

And make the passing Minutes sweetly smile,

Can we, like Shepherds, tell a merry Tale?

The Voice is lost, drown’d by the noisy Flail. . .

Week after Week we this dull Task pursue,

Unless when winnowing Days produce a new;

A new indeed, but frequently a worse,

The Threshall yields but to the Master’s Curse:

He counts the Bushels, counts how much a Day,

Then swears we’ve idled half our Time away.

Why look ye, Rogues! D’ye think that this will do?

Your Neighbours thresh as much again as you.

This would appear to describe the monotony, alienation from pleasure in labour, and antagonism of interests commonly ascribed to the factory system. The second passage describes the harvesting:

At length in Rows stands up the well-dry’d Corn,

A grateful Scene, and ready for the Barn.

Our well-pleas’d Master views the Sight with joy,

And we for carrying all our Force employ.

Confusion soon o’er all the Field appears,

And stunning Clamours fill the Workmens Ears;

The Bells, and clashing Whips, alternate sound,

And rattling Waggons thunder o’er the Ground.

The Wheat got in, the Pease, and other Grain,

Share the same Fate, and soon leave bare the Plain:

In noisy Triumph the last Load moves on,

And loud Huzza’s proclaim the Harvest done.

This is, of course, an obligatory set-piece in eighteenth-century farming poetry. And it is also true that the good morale of the labourers was sustained by their high harvest earnings. But it would be an error to see the harvest situation in terms of direct responses to economic stimuli. It is also a moment at which the older collective rhythms break through the new, and a weight of folklore and of rural custom could be called as supporting evidence as to the psychic satisfaction and ritual functions — for example, the momentary obliteration of social distinctions — of the harvest-home. “How few now know”, M. K. Ashby writes, “what it was ninety years ago to get in a harvest! Though the disinherited had no great part of the fruits, still they shared in the achievement, the deep involvement and joy of it”.11

III

It is by no means clear how far the availability of precise clock time extended at the time of the industrial revolution. From the fourteenth century onwards church clocks and public clocks were erected in the cities and large market towns. The majority of English parishes must have possessed church clocks by the end of the sixteenth century.22 But the accuracy of these clocks is a matter of dispute; and the sundial remained in use (partly to set the clock) in the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.33

Charitable donations continued to be made in the seventeenth century (sometimes laid out in “clockland”, “ding dong land”, or “curfew bell land”) for the ringing of early morning bells and curfew bells.11 Thus Richard Palmer of Wokingham (Berkshire) gave, in 1664, lands in trust to pay the sexton to ring the great bell for half an hour every evening at eight o’clock and every morning at four o’clock, or as near to those hours as might be, from the 10th September to the 11th March in each year

not only that as many as might live within the sound might be thereby induced to a timely going to rest in the evening, and early arising in the morning to the labours and duties of their several callings, (things ordinarily attended and rewarded with thrift and proficiency). . .

but also so that strangers and others within sound of the bell on winter nights “might be informed of the time of night, and receive some guidance into their right way”. These “rational ends”, he conceived, “could not but be well liked by any discreet person, the same being done and well approved of in most of the cities and market-towns, and many other places in the kingdom. . .”. The bell would also remind men of their passing, and of resurrection and judgement.22 Sound served better than sight, especially in growing manufacturing districts. In the clothing districts of the West Riding, in the Potteries, (and probably in other districts) the horn was still used to awaken people in the mornings.33 The farmer aroused his own labourers, on occasion, from their cottages; and no doubt the knocker-up will have started with the earliest mills.

A great advance in the accuracy of household clocks came with the application of the pendulum after 1658. Grandfather clocks began to spread more widely from the 1660s, but clocks with minute hands (as well as hour hands) only became common well after this time.11 As regards more portable time, the pocket watch was of dubious accuracy until improvements were made in the escapement and the spiral balance-spring was applied after 1674.22 Ornate and rich design was still preferred to plain serviceability. A Sussex diarist notes in 1688:

bought. . . a silver-cased watch, weh cost me 3Ii. . . This watch shewes ye hour of ye day, ye month of ye year, ye age of ye moon, and ye ebbing and flowing of ye water; and will goe 30 hours with one winding up.33

Professor Cipolla suggests 1680 as the date at which English clock- and watch-making took precedence (for nearly a century) over European competitors.44 Clock-making had emerged from the skills of the blacksmith,55 and the affinity can still be seen in the many hundreds of independent clock-makers, working to local orders in their own shops, dispersed through the market-towns and even the large villages of England, Scotland and Wales in the eighteenth century.66 While many of these aspired to nothing more fancy than the work-a-day farmhouse longcase clock, craftsmen of genius were among their numbers. Thus John Harrison, clock-maker and former carpenter of Barton-on-Humber (Lincolnshire), perfected a marine chronometer, and in 1730 could claim to have

brought a Clock to go nearer the truth, than can be well imagin’d, considering the vast Number of seconds of Time there is in a Month, in which space of time it does not vary above one second. . . I am sure I can bring it to the nicety of 2 or 3 seconds in a year.11

And John Tibbot, a clock-maker in Newtown (Montgomeryshire), had perfected a clock in 1810 which (he claimed) seldom varied more than a second over two years.22 In between these extremes were those numerous, shrewd, and highly-capable craftsmen who played a critically important role in technical innovation in the early stages of the industrial revolution. The point, indeed, was not left for historians to discover: it was argued forcibly in petitions of the clock- and watch-makers against the assessed taxes in February 1798. Thus the petition from Carlisle:

. . . the cotton and woollen manufactories are entirely indebted for the state of perfection to which the machinery used therein is now brought to the clock and watch makers, great numbers of whom have, for several years past. . . been employed in inventing and constructing as well as superintending such machinery. . .33

Small-town clock-making survived into the eighteenth century, although from the early years of that century it became common for the local clock-maker to buy his parts ready-made from Birmingham, and to assemble these in his own workshop. By contrast, watch-making, from the early years of the eighteenth century, was concentrated in a few centres, of which the most important were London, Coventry, Prescot and Liverpool.11 A minute subdivision of labour took place in the industry early, facilitating large-scale production and a reduction in prices: the annual output of the industry at its peak (1796) was variously estimated at 120,000 and 191,678, a substantial part of which was for the export market.22 Pitt’s ill-judged attempt to tax clocks and watches, although it lasted only from July 1797 to March 1798, marked a turning-point in the fortunes of the industry. Already, in 1796, the trade was complaining at the competition of French and Swiss watches; the complaints continue to grow in the early years of the nineteenth century. The Clockmakers’ Company alleged in 1813 that the smuggling of cheap gold watches had assumed major proportions, and that these were sold by jewellers, haberdashers, milliners, dressmakers, French toy-shops, perfumers, etc., “almost entirely for the use of the upper classes of society”. At the same time, some cheap smuggled goods, sold by pawnbrokers or travelling salesmen, must have been reaching the poorer classes.33

It is clear that there were plenty of watches and clocks around by 1800. But it is not so clear who owned them. Dr Dorothy George, writing of the mid eighteenth century, suggests that “labouring men, as well as artisans, frequently possessed silver watches”, but the statement is indefinite as to date and only slightly documented.11 The average price of plain longcase clocks made locally in Wrexham between 1755 and 1774 ran between £2 and £2 15s. 0d.; a Leicester price-list for new clocks, without cases, in 1795 runs between £3 and £5. A well-made watch would certainly cost no less.22 On the face of it, no labourer whose budget was recorded by Eden or David Davies could have meditated such prices, and only the best-paid urban artisan. Recorded time (one suspects) belonged in the mid-century still to the gentry, the masters, the farmers and the tradesmen; and perhaps the intricacy of design, and the preference for precious metal, were in deliberate accentuation of their symbolism of status.

But, equally, it would appear that the situation was changing in the last decades of the century. The debate provoked by the attempt to impose a tax on all clocks and watches in 1797-8 offers a little evidence. It was perhaps the most unpopular and it was certainly the most unsuccessful of all of Pitt’s assessed taxes:

If your Money he take — why your Breeches remain;

And the flaps of your Shirts, if your Breeches he gain;

And your Skin, if your Shirts; and if Shoes, your bare feet.

Then, never mind TAXES — We’ve beat the Dutch fleet!33

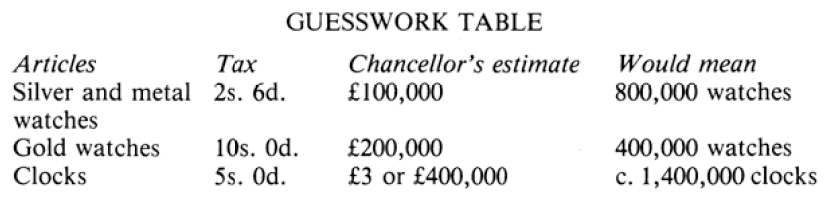

The taxes were of 2s. 6d. upon each silver or metal watch; 10s. upon each gold one; and 5s. upon each clock. In debates upon the tax, the statements of ministers were remarkable only for their contradictions. Pitt declared that he expected the tax to produce £200,000 per annum:

In fact, he thought, that as the number of houses paying taxes is 700,000 and that in every house there is probably one person who wears a watch, the tax upon watches only would produce that sum.

At the same time, in response to criticism, ministers maintained that the ownership of clocks and watches was a mark of luxury. The Chancellor of the Exchequer faced both ways: watches and clocks “were certainly articles of convenience, but they were also articles of luxury. . . generally kept by persons who would be pretty well able to pay. . .”. “He meant, however, to exempt Clocks of the meaner sort that were most commonly kept by the poorer classes.”11 The Chancellor clearly regarded the tax as a sort of Lucky Bag; his guess was more than three times that of the Pilot:

His eyes glittering at the prospect of enhanced revenue, Pitt revised his definitions: a single watch (or dog) might be owned as an article of convenience — more than this were “tests of affluence”.22

Unfortunately for the quantifiers of economic growth, one matter was left out of account. The tax was impossible to collect.33 All householders were ordered, upon dire pains, to return lists of clocks and watches within their houses. Assessments were to be quarterly:

Mr. Pitt has very proper ideas of the remaining finances of the country. The half-crown tax upon watches is appointed to be collected quarterly. This is grand and dignified. It gives a man an air of consequence to pay sevenpence halfpenny to support religion, property, and social order.11

In fact, the tax was regarded as folly; as setting up a system of espionage; and as a blow against the middle class.22 There was a buyer’s strike. Owners of gold watches melted down the covers and exchanged them for silver or metal.33 The centres of the trade were plunged into crisis and depression.44 Repealing the Act in March 1798, Pitt said sadly that the tax would have been productive much beyond the calculation originally made; but it is not clear whether it was his own calculation (£200,000) or the Chancellor of the Exchequer’s (£700,000) which he had in mind.55

We remain (but in the best of company) in ignorance. There were a lot of timepieces about in the 1790s: emphasis is shifting from “luxury” to “convenience”; even cottagers may have wooden clocks costing less than twenty shillings. Indeed, a general diffusion of clocks and watches is occurring (as one would expect) at the exact moment when the industrial revolution demanded a greater synchronisation of labour.

Although some very cheap — and shoddy — time-pieces were beginning to appear, the prices of efficient ones remained for several decades beyond the normal reach of the artisan.66 But we should not allow normal economic preferences to mislead us. The small instrument which regulated the new rhythms of industrial life was at the same time one of the more urgent of the new needs which industrial capitalism called forth to energise its advance. A clock or watch was not only useful; it conferred prestige upon its owner, and a man might be willing to stretch his resources to obtain one. There were various sources, various occasions. For decades a trickle of sound but cheap watches found their way from the pickpocket to the receiver, the pawnbroker, the public house.11 Even labourers, once or twice in their lives, might have an unexpected windfall, and blow it on a watch: the militia bounty,22 harvest earnings, or the yearly wages of the servant.33 In some parts of the country Clock and Watch Clubs were set up — collective hire-purchase.44 Moreover, the time-piece was the poor man’s bank, an investment of savings: it could, in bad times, be sold or put in hock.11 “This ’ere ticker”, said one Cockney compositor in the 1820s, “cost me but a five-pun note ven I bort it fust, and I’ve popped it more than twenty times, and had more than forty poun’ on it altogether. It’s a garjian haingel to a fellar, is a good votch, ven you’re hard up”.22

Whenever any group of workers passed into a phase of improving living standards, the acquisition of time-pieces was one of the first things noted by observers. In Radcliffe’s well-known account of the golden age of the Lancashire hand-loom weavers in the 1790s the men had “each a watch in his pocket” and every house was “well furnished with a clock in elegant mahogany or fancy case”.33 In Manchester fifty years later the same point caught a reporter’s eye:

No Manchester operative will be without one a moment longer than he can help. You see, here and there, in the better class of houses, one of the old-fashioned, metallic-faced eight-day clocks; but by far the most common article is the little Dutch machine, with its busy pendulum swinging openly and candidly before all the world.44

Thirty years later again it was the gold double watch-chain which was the symbol of the successful Lib-Lab trade union leader; and for fifty years of disciplined servitude to work, the enlightened employer gave to his employee an engraved gold watch.

IV

Let us return from the time-piece to the task. Attention to time in labour depends in large degree upon the need for the synchronisation of labour. But in so far as manufacturing industry remained conducted upon a domestic or small workshop scale, without intricate subdivision of processes, the degree of synchronisation demanded was slight, and task-orientation was still prevalent.11 The putting-out system demanded much fetching, carrying, waiting for materials. Bad weather could disrupt not only agriculture, building and transport, but also weaving, where the finished pieces had to be stretched on the tenters to dry. As we get closer to each task, we are surprised to find the multiplicity of subsidiary tasks which the same worker or family group must do in one cottage or workshop. Even in larger workshops men sometimes continued to work at distinct tasks at their own benches or looms, and — except where the fear of the embezzlement of materials imposed stricter supervision — could show some flexibility in coming and going.

Hence we get the characteristic irregularity of labour patterns before the coming of large-scale machine-powered industry. Within the general demands of the week’s or fortnight’s tasks — the piece of cloth, so many nails or pairs of shoes — the working day might be lengthened or shortened. Moreover, in the early development of manufacturing industry, and of mining, many mixed occupations survived: Cornish tinners who also took a hand in the pilchard fishing; Northern lead-miners who were also smallholders; the village craftsmen who turned their hands to various jobs, in building, carting, joining; the domestic workers who left their work for the harvest; the Pennine small-farmer/weaver.

It is in the nature of such work that accurate and representative time-budgets will not survive. But some extracts from the diary of one methodical farming weaver in 1782-83 may give us an indication of the variety of tasks. In October 1782 he was still employed in harvesting, and threshing, alongside his weaving. On a rainy day he might weave 8

![]() or 9 yards; on October 14th he carried his finished piece, and so wove only 4

or 9 yards; on October 14th he carried his finished piece, and so wove only 4

![]() yards; on the 23rd he “worked out” till 3 o’clock, wove two yards before sunset, “clouted [mended] my coat in the evening”. On December 24th “wove 2 yards before 11 o’clock. I was laying up the coal heap, sweeping the roof and walls of the kitchen and laying the muck [midden?] till 10 o’clock at night.” Apart from harvesting and threshing, churning, ditching and gardening, we have these entries:

yards; on the 23rd he “worked out” till 3 o’clock, wove two yards before sunset, “clouted [mended] my coat in the evening”. On December 24th “wove 2 yards before 11 o’clock. I was laying up the coal heap, sweeping the roof and walls of the kitchen and laying the muck [midden?] till 10 o’clock at night.” Apart from harvesting and threshing, churning, ditching and gardening, we have these entries:

January 18, 1783: “I was employed in preparing a Calf stall & Fetching the Tops of three Plain Trees home which grew in the Lane and was that day cut down & sold to john Blagbrough.”

January 21st: “Wove 2![]()

![]() yards the Cow having calved she required much attendance.” (On the next day he walked to Halifax to buy medicine for the cow.)

yards the Cow having calved she required much attendance.” (On the next day he walked to Halifax to buy medicine for the cow.)

On January 25th he wove 2 yards, walked to a nearby village, and did “sundry jobs about the lathe and in the yard & wrote a letter in the evening”. Other occupations include jobbing with a horse and cart, picking cherries, working on a mill dam, attending a Baptist association and a public hanging.11

This general irregularity must be placed within the irregular cycle of the working week (and indeed of the working year) which provoked so much lament from moralists and mercantilists in the seventeenth centuries. A rhyme printed in 1639 gives us a satirical version:

You know that Munday is Sundayes brother;

Tuesday is such another;

Wednesday you must go to Church and pray;

Thursday is half-holiday;

On Friday it is too late to begin to spin;

The Saturday is half-holiday again.11

John Houghton, in 1681, gives us the indignant version:

When the framework knitters or makers of silk stockings had a great price for their work, they have been observed seldom to work on Mondays and Tuesdays but to spend most of their time at the ale-house or nine-pins. . . The weavers, ’tis common with them to be drunk on Monday, have their head-ache on Tuesday, and their tools out of order on Wednesday. As for the shoemakers, they’ll rather be hanged than not remember St. Crispin on Monday. . . and it commonly holds as long as they have a penny of money or pennyworth of credit.22

The work pattern was one of alternate bouts of intense labour and of idleness, wherever men were in control of their own working lives. (The pattern persists among some self-employed — artists, writers, small farmers, and perhaps also with students — today, and provokes the question whether it is not a “natural” human work-rhythm.) On Monday or Tuesday, according to tradition, the hand-loom went to the slow chant of Plen-ty of Time, Plen-ty of Time: On Thursday and Friday, A day t’lat, A day t’lat.33 The temptation to lie in an extra hour in the morning pushed work into the evening, candle-lit hours.44 There are few trades which are not described as honouring Saint Monday: shoemakers, tailors, colliers, printing workers, potters, weavers, hosiery workers, cutlers, all Cockneys. Despite the full employment of many London trades during the Napoleonic Wars, a witness complained that “we see Saint Monday so religiously kept in this great city. . . in general followed by a Saint Tuesday also”.11 If we are to believe “The Jovial Cutlers”, a Sheffield song of the late eighteenth century, its observance was not without domestic tension:

How upon a good Saint Monday,

Sitting by the smithy fire,

Telling what’s been done o’t Sunday,

And in cheerful mirth conspire,

Soon I hear the trap-door rise up,

On the ladder stands my wife:

“Damn thee, Jack, I’ll dust they eyes up,

Thou leads a plaguy drunken life;

Here thou sits instead of working,

Wi’ thy pitcher on thy knee;

Curse thee, thou’d be always lurking.

And I may slave myself for thee”.

The wife proceeds, speaking “with motion quicker/Than my boring stick at a Friday’s pace”, to demonstrate effective consumer demand:

“See thee, look what stays I’ve gotten,

See thee, what a pair o’ shoes;

Gown and petticoat half rotten,

Ne’er a whole stitch in my hose. . .”

and to serve notice of a general strike:

“Thou knows I hate to broil and quarrel,

But I’ve neither soap nor tea;

Od burn thee, Jack, forsake thy barrel,

Or nevermore thou’st lie wi’ me”.22

Saint Monday, indeed, appears to have been honoured almost universally wherever small-scale, domestic, and outwork industries existed; was generally found in the pits; and sometimes continued in manufacturing and heavy industry.11 It was perpetuated, in England, into the nineteenth — and, indeed, into the twentieth22 — century for complex economic and social reasons. In some trades, the small masters themselves accepted the institution, and employed Monday in taking-in or giving-out work. In Sheffield, where the cutlers had for centuries tenaciously honoured the Saint, it had become “a settled habit and custom” which the steel-mills themselves honoured (1874):

This Monday idleness is, in some cases, enforced by the fact that Monday is the day that is taken for repairs to the machinery of the great steelworks.33

Where the custom was deeply-established, Monday was the day set aside for marketing and personal business. Also, as Duveau suggests of French workers, “le dimanche est le jour de la famille, le lundi celui de l’amitié”; and as the nineteenth century advanced, its celebration was something of a privilege of status of the better-paid artisan.11

It is, in fact, in an account by “An Old Potter” published as late as 1903 that we have some of the most perceptive observations on the irregular work-rhythms which continued on the older pot-banks until the mid-century. The potters (in the 1830s and 1840s) “had a devout regard for Saint Monday”. Although the custom of annual hiring prevailed, the actual weekly earnings were at piece-rates, the skilled male potters employing the children, and working, with little supervision, at their own pace. The children and women came to work on Monday and Tuesday, but a “holiday feeling” prevailed and the day’s work was shorter than usual, since the potters were away a good part of the time, drinking their earnings of the previous week. The children, however, had to prepare work for the potter (for example, handles for pots which he would throw), and all suffered from the exceptionally long hours (fourteen and sometimes sixteen hours a day) which were worked from Wednesday to Saturday:

I have since thought that but for the reliefs at the beginning of the week for the women and boys all through the pot-works, the deadly stress of the last four days could not have been maintained.

“An Old Potter”, a Methodist lay preacher of Liberal-Radical views, saw these customs (which he deplored) as a consequence of the lack of mechanisation of the pot-banks; and he urged that the same indiscipline in daily work influenced the entire way of life and the working-class organisations of the Potteries. “Machinery means discipline in industrial operations”:

If a steam-engine had started every Monday morning at six o’clock, the workers would have been disciplined to the habit of regular and continuous industry. . . I have noticed, too, that machinery seems to lead to habits of calculation. The Pottery workers were woefully deficient in this matter; they lived like children, without any calculating forecast of their work or its result. In some of the more northern counties this habit of calculation has made them keenly shrewd in many conspicuous ways. Their great co-operative societies would never have arisen to such immense and fruitful development but for the calculating induced by the use of machinery. A machine worked so many hours in the week would produce so much length of yarn or cloth. Minutes were felt to be factors in these results, whereas in the Potteries hours, or even days at times, were hardly felt to be such factors. There were always the mornings and nights of the last days of the week, and these were always trusted to make up the loss of the week’s early neglect.11

This irregular working rhythm is commonly associated with heavy week-end drinking: Saint Monday is a target in many Victorian temperance tracts. But even the most sober and self-disciplined artisan might feel the necessity for such alternations. “I know not how to describe the sickening aversion which at times steals over the working man and utterly disables him for a longer or shorter period, from following his usual occupation”, Francis Place wrote in 1829; and he added a footnote of personal testimony:

For nearly six years, whilst working, when I had work to do, from twelve to eighteen hours a day, when no longer able, from the cause mentioned, to continue working, I used to run from it, and go as rapidly as I could to Highgate, Hampstead, Muswell-hill, or Norwood, and then “return to my vomit”. . . This is the case with every workman I have ever known; and in proportion as a man’s case is hopeless will such fits more frequently occur and be of longer duration.22

We may, finally, note that the irregularity of working day and week were framed, until the first decades of the nineteenth century, within the larger irregularity of the working year, punctuated by its traditional holidays, and fairs. Still, despite the triumph of the Sabbath over the ancient saints’ days in the seventeenth century,11 the people clung tenaciously to their customary wakes and feasts, and may even have enlarged them both in vigour and extent.22

How far can this argument be extended from manufacturing industry to the rural labourers? On the face of it, there would seem to be unrelenting daily and weekly labour here: the field labourer had no Saint Monday. But a close discrimination of different work-situations is still required. The eighteenth- (and nineteenth-) century village had its own self-employed artisans, as well as many employed on irregular task work.33 Moreover, in the unenclosed countryside, the classical case against open field and common was in its inefficiency and wastefulness of time, for the small farmer or cottager:

. . . if you offer them work, they will tell you that they must go to look up their sheep, cut furzes, get their cow out of the pound, or, perhaps, say they must take their horse to be shod, that he may carry them to a horse-race or cricket-match (Arbuthnot, 1773.)

In sauntering after his cattle, he acquires a habit of indolence. Quarter, half, and occasionally whole days are imperceptibly lost. Day labour becomes disgusting. . . (Report on Somerset, 1795.)

Whenalabourerbecomespossessedofmorelandthanheandhis family can cultivate in the evenings. . . the farmer can no longer depend on him for constant work. . . (Commercial & Agricultural Magazine, 1800.)44

To this we should add the frequent complaints of agricultural improvers as to the time wasted, both at seasonal fairs, and (before the arrival of the village shop) on weekly market days.11

The farm servant, or the regular wage-earning field labourer, who worked, unremittingly, the full statute hours or longer, who had no common rights or land, and who (if not living-in) lived in a tied cottage, was undoubtedly subject to an intense labour discipline, whether in the seventeenth or the nineteenth century. The day of a ploughman (living-in) was described with relish by Markham in 1636:

. . . the Plowman shall rise before four of the clock in the morning, and after thanks given to God for his rest, & prayer for the success of his labours, he shall go into his stable. . .

After cleansing the stable, grooming his horses, feeding them, and preparing his tackle, he might breakfast (6-6.30 a.m.), he should plough until 2 p.m. or 3 p.m., take half an hour for dinner; attend to his horses etc. until 6.30 p.m., when he might come in for supper:

. . . and after supper, hee shall either by the fire side mend shooes both for himselfe and their Family, or beat and knock Hemp or Flax, or picke and stamp Apples or Crabs, for Cyder or Verdjuyce, or else grind malt on the quernes, pick candle rushes, or doe some Husbandly office within doors till it be full eight a clock. . .

Then he must once again attend to his cattle and (“giving God thanks for benefits received that day”) he might retire.22

Even so, we are entitled to show a certain scepticism. There are obvious difficulties in the nature of the occupation. Ploughing is not an all-the-year-round task. Hours and tasks must fluctuate with the weather. The horses (if not the men) must be rested. There is the difficulty of supervision: Robert Loder’s accounts indicate that servants (when out of sight) were not always employed upon their knees thanking God for their benefits: “men can worke yf they list & soe they can loyter”.11 The farmer himself must work exceptional hours if he was to keep all his labourers always employed.22 And the farm servant could assert his annual right to move on if he disliked his employment.

Thus enclosure and agricultural improvement were both, in some sense, concerned with the efficient husbandry of the time of the labour-force. Enclosure and the growing labour-surplus at the end of the eighteenth century tightened the screw for those who were in regular employment; they were faced with the alternatives of partial employment and the poor law, or submission to a more exacting labour discipline. It is a question, not of new techniques, but of a greater sense of time-thrift among the improving capitalist employers. This reveals itself in the debate between advocates of regularly-employed wage-labour and advocates of “taken-work” (i.e. labourers employed for particular tasks at piece-rates). In the 1790s Sir Mordaunt Martin censured recourse to taken-work

which people agree to, to save themselves the trouble of watching their workmen: the consequence is, the work is ill done, the workmen boast at the ale-house what they can spend in “a waste against the wall”, and make men at moderate wages discontented.

“A Farmer” countered with the argument that taken-work and regular wage-labour might be judiciously intermixed:

Two labourers engage to cut down a piece of grass at two shillings or half-a-crown an acre; I send, with their scythes, two of my domestic farm-servants into the field; I can depend upon it, that their companions will keep them up to their work; and thus I gain. . . the same additional hours of labour from my domestic servants, which are voluntarily devoted to it by my hired servants.33