20.

Foreword

In her great work, The Making of Ireland and Its Undoing, the only contribution to Irish history we know of which conforms to the methods of modern historical science, the authoress, Mrs. Stopford Green, dealing with the effect upon Ireland of the dispersion of the Irish race in the time of Henry VIII and Elizabeth, and the consequent destruction of Gaelic culture, and rupture with Gaelic tradition and law, says that the Irishmen educated in schools abroad abandoned or knew nothing of the lore of ancient Erin, and had no sympathy with the spirit of the Brehon Code, nor with the social order of which it was the juridical expression. She says they “urged the theory, so antagonistic to the immemorial law of Ireland, that only from the polluted sinks of heretics could come the idea that the people might elect a ruler, and confer supreme authority on whomsoever pleased them.” In other words, the new Irish, educated in foreign standards, had adopted as their own the feudal-capitalist system of which England was the exponent in Ireland, and urged it upon the Gaelic Irish. As the dispersion of the clans, consummated by Cromwell, finally completed the ruin of Gaelic Ireland, all the higher education of Irishmen thenceforward ran in this foreign groove, and was colored with this foreign coloring.

In other words, the Gaelic culture of the Irish chieftainry was rudely broken off in the seventeenth century, and the continental schools of European despots implanted in its place in the minds of the Irish students, and sent them back to Ireland to preach a fanatical belief in royal and feudal prerogatives, as foreign to the genius of the Gael as was the English ruler to Irish soil. What a light this sheds upon Irish history of the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries! And what a commentary it is upon the real origin of that so-called “Irish veneration for the aristocracy,” of which the bourgeois charlatans of Irish literature write so eloquently! That veneration is seen to be as much of an exotic, as much of an importation, as the aristocratic caste it venerated. Both were

“… foul foreign blossoms Blown hither to poison our plains.”

But so deeply has this insidious lie about the aristocratic tendencies of the Irish taken root in Irish thought, that it will take a long time to eradicate it from the minds of the people, or to make the Irish realize that the whole concept of orthodox Irish history for the last two hundred years was a betrayal and abandonment of the best traditions of the Irish race. Yet such is undoubtedly the case. Let us examine this a little more closely!

Just as it is true that a stream cannot rise above its source, so it is true that a national literature cannot rise above the moral level of the social conditions of the people from whom it derives its inspiration. If we would understand the national literature of a people, we must study their social and political status, keeping in mind the fact that their writers were a product thereof, and that the children of their brains were conceived and brought forth in certain historical conditions. Ireland, at the same time as she lost her ancient social system, also lost her language as the vehicle of thought of those who acted as her leaders. As a result of this twofold loss, the nation suffered socially, nationally, and intellectually from a prolonged arrested development. During the closing years of the seventeenth century, all the eighteenth, and the greater part of the nineteenth, the Irish people were the lowest helots in Europe, socially and politically. The Irish peasant, reduced from the position of a free clansman owning his tribeland and controlling its administration in common with his fellows, was a mere tenant-at-will subject to eviction, dishonor, and outrage at the hands of an irresponsible private proprietor. Politically he was nonexistent, legally he held no rights, intellectually he sank under the weight of his social abasement, and surrendered to the downward drag of his poverty. He had been conquered, and he suffered all the terrible consequences of defeat at the hands of a ruling class and nation who have always acted upon the old Roman maxim of “Woe to the vanquished.”

To add to his humiliation, those of his name and race who had contrived to escape the general ruin, and sent their children to be educated in foreign schools, discovered, with the return of those “wild geese” to their native habitat, that they who had sailed for France, Italy, or Spain, filled with hatred of the English Crown and of the English landlord garrison in Ireland, returned as mere Catholic adherents of a pretender to the English throne, using all the prestige of their foreign schooling to discredit the Gaelic ideas of equality and democracy, and instead instilling into the minds of the growing generation feudal ideas of the divine right of kings to rule, and of subjects to unquestioningly obey. The Irish students in the universities of the Continent were the first products of a scheme which the papacy still pursues with its accustomed skill and persistence—a persistence which recks little of the passing of centuries—a scheme which looks upon Catholic Ireland simply as a tool to be used for the spiritual reconquest of England to Catholicity. In the eighteenth century this scheme did its deadliest work in Ireland. It failed ridiculously to cause a single Irish worker in town or country to strike a blow for the Stuart cause in the years of the Scottish Rebellions in 1715 and 1745, but it prevented them from striking any blows for their own cause, or from taking advantage of the civil feuds of their enemies. It did more. It killed Gaelic Ireland; an Irish-speaking Catholic was of no value as a missionary of Catholicism in England, and an Irish peasant who treasured the tongue of his fathers might also have some reverence for the principles of the social polity and civilization under which his forefathers had lived and prospered for unnumbered years. And such principles were even more distasteful to French, Spanish, or Papal patrons of Irish schools of learning on the Continent than they were to English monarchs. Thus the poor Irish were not only pariahs in the social system of their day, but they were also precluded from hoping for a revival of intellectual life through the achievements of their children. Their children were taught to despise the language and traditions of their fathers.

It was at or during this period, when the Irish peasant had been crushed to the very lowest point, when the most he could hope for was to be pitied as animals are pitied; it was during this period Irish literature in English was born. Such Irish literature was not written for Irishmen as a real Irish literature would be, it was written by Irishmen, about Irishmen, but for English or Anglo-Irish consumption.

Hence the Irishman in English literature may be said to have been born with an apology in his mouth. His creators knew nothing of the free and independent Irishman of Gaelic Ireland, but they did know the conquered, robbed, slave-driven, brutalized, demoralized Irishman, the product of generations of landlord and capitalist rule, and him they seized upon, held up to the gaze of the world, and asked the nations to accept as the true Irish type.

If he crouched before a representative of royalty with an abject submission born of a hundred years of political outlawry and training in foreign ideas, his abasement was pointed to proudly as an instance of the “ancient Celtic fidelity to hereditary monarchs”; if, with the memory of perennial famines, evictions, jails, hangings, and tenancy-at-will beclouding his brain, he humbled himself before the upper class, or attached himself like a dog to their personal fortunes, his sycophancy was cited as a manifestation of “ancient Irish veneration for the aristocracy,” and if long-continued insecurity of life begat in him a fierce desire for the ownership of a piece of land to safeguard his loved ones in a system where land was life, this newborn land hunger was triumphantly trumpeted forth as a proof of the “Irish attachment to the principle of private property.”’ Be it understood we are not talking now of the English slanderers of the Irishman, but of his Irish apologists. The English slanderer never did as much harm as did these self-constituted delineators of Irish characteristics. The English slanderer lowered Irishmen in the eyes of the world, but his Irish middle-class teachers and writers lowered him in his own eyes by extolling as an Irish virtue every sycophantic vice begotten of generations of slavery. Accordingly, as an Irishman, peasant, laborer, or artisan, banded himself with his fellows to strike back at their oppressors in defense of their right to live in the land of their fathers, the “respectable” classes who had imbibed the foreign ideas publicly deplored his act, and unctuously ascribed it to the “evil effects of English misgovernment upon the Irish character”; but when an occasional Irishman, abandoning all the traditions of his race, climbed up upon the backs of his fellows to wealth or position, his career was held up as a sample of what Irishmen could do under congenial or favorable circumstances. The seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries were, indeed, the Via Dolorosa of the Irish race. In them the Irish Gael sank out of sight, and in his place the middle-class politicians, capitalists, and ecclesiastics labored to produce a hybrid Irishman, assimilating a foreign social system, a foreign speech, and a foreign character. In the effort to assimilate the first two the Irish were unhappily too successful, so successful that today the majority of the Irish do not know that their fathers ever knew another system of ownership, and the Irish Irelanders are painfully grappling with their mother tongue with the hesitating accent of a foreigner. Fortunately the Irish character has proven too difficult to press into respectable foreign molds, and the recoil of that character from the deadly embrace of capitalist English conventionalism, as it has already led to a revaluation of the speech of the Gael, will in all probability also lead to a restudy and appreciation of the social system under which the Gael reached the highest point of civilization and culture in Europe.

In the reconversion of Ireland to the Gaelic principle of common ownership by a people of their sources of food and maintenance, the worst obstacles to overcome will be the opposition of the men and women who have imbibed their ideas of Irish character and history from Anglo-Irish literature. That literature, as we have explained, was born in the worst agonies of the slavery of our race; it bears all the birthmarks of such origin upon it, but irony of ironies, these birthmarks of slavery are hailed by our teachers as “the native characteristics of the Celt.”

One of these slave birthmarks is a belief in the capitalist system of society; the Irishman frees himself from such a mark of slavery when he realizes the truth that the capitalist system is the most foreign thing in Ireland.

Hence we have had in Ireland for over 250 years the remarkable phenomenon of Irishmen of the upper and middle classes urging upon the Irish toilers, as a sacred national and religious duty, the necessity of maintaining a social order against which their Gaelic forefathers had struggled, despite prison cells, famine, and the sword, for over 400 years. Reversing the procedure of the Normans settled in Ireland, who were said to have become “more Irish than the Irish,” the Irish propertied classes became more English than the English, and so have continued to our day.

Hence we believe that this book, attempting to depict the attitude of the dispossessed masses of the Irish people in the great crisis of modern Irish history, may justly be looked upon as part of the literature of the Gaelic revival. As the Gaelic language, scorned by the possessing classes, sought and found its last fortress in the hearts and homes of the “lower orders,” to reissue from thence in our own time to what the writer believes to be a greater and more enduring place in civilization than of old, so in the words of Thomas Francis Meagher, the same “wretched cabins have been the holy shrines in which the traditions and the hopes of Ireland have been treasured and transmitted.”

The apostate patriotism of the Irish capitalist class, arising as it does upon the rupture with Gaelic tradition, will, of course, reject this conception, and saturated with foreignism themselves, they will continue to hurl the epithet of “foreign ideas” against the militant Irish democracy. But the present Celtic revival in Ireland, leading as it must to a reconsideration and more analytical study of the laws and social structure of Ireland before the English Invasion, amongst its other good results, will have this one also, that it will confirm and establish the truth of this conception. Hitherto the study of the social structure of Ireland in the past has been marred by one great fault. For a description and interpretation of Irish social life and customs, the student depended entirely upon the description and interpretation of men who were entirely lacking in knowledge of, and insight into, the facts and spirit of the things they attempted to describe. Imbued with the conception of feudalistic or capitalistic social order, the writers perpetually strove to explain Irish institutions in terms of an order of things to which those institutions were entirely alien. Irish titles, indicative of the function in society performed by their bearers, the writers explained by what they supposed were analogous titles in the feudal order of England, forgetful of the fact that, as the one form of society was the antithesis of the other, and not its counterpart, the one set of titles could not possibly convey the same meaning as the other, much less be a translation.

Much the same mistake was made in America by the early Spanish conquistadores in attempting to describe the social and political systems of Mexico and Peru, with much the same results of introducing almost endless confusion into every attempt to comprehend life as it actually existed in those countries before the conquest. The Spanish writers could not mentally raise themselves out of the social structure of continental Europe, and hence their weird and wonderful tales of despotic Peruvian and Mexican “emperors” and “nobles” where really existed the elaborately organized family system of a people not yet fully evolved into the political state. Not until the publication of Morgan’s monumental work on ancient society was the key to the study of American native civilization really found and placed in the hands of the student. The same key will yet unlock the doors which guard the secrets of our native Celtic civilization, and make them possible of fuller comprehension for the multitude.

Meanwhile we desire to place before our readers the two propositions upon which this book is founded—propositions which we believe embody alike the fruits of the experience of the past, and the matured thought of the present, upon the points under consideration.

First, that in the evolution of civilization the progress of the fight for national liberty of any subject nation must, perforce, keep pace with the progress of the struggle for liberty of the most subject class in that nation, and that the shifting of economic and political forces which accompanies the development of the system of capitalist society leads inevitably to the increasing conservatism of the non-working-class element, and to the revolutionary vigor and power of the working class.

Second, that the result of the long drawn-out struggle of Ireland has been, so far, that the old chieftainry has disappeared, or, through its degenerate descendants, has made terms with iniquity, and become part and parcel of the supporters of the established order; the middle class, growing up in the midst of the national struggle, and at one time, as in 1798, through the stress of the economic rivalry of England almost forced into the position of revolutionary leaders against the political despotism of their industrial competitors, have now also bowed the knee to Baal, and have a thousand economic strings in the shape of investments binding them to English capitalism as against every sentimental or historic attachment drawing them toward Irish patriotism; only the Irish working class remain as the incorruptible inheritors of the fight for freedom in Ireland.

To that unconquered Irish working class this book is dedicated by one of their number.

Chapter I. The Lessons of History

What is history but a fable agreed upon.

—Napoleon I

It is in itself a significant commentary upon the subordinate place allotted to labor in Irish politics that a writer should think it necessary to explain his purpose before setting out to detail for the benefit of his readers the position of the Irish workers in the past, and the lessons to be derived from a study of that position in guiding the movement of the working class today. Were history what it ought to be, an accurate literary reflex of the times with which it professes to deal, the pages of history would be almost entirely engrossed with a recital of the wrongs and struggles of the laboring people, constituting, as they have ever done, the vast mass of mankind. But history in general treats the working class as the manipulator of politics treats the working man—that is to say, with contempt when he remains passive, and with derision, hatred, and misrepresentation whenever he dares evince a desire to throw off the yoke of political or social servitude. Ireland is no exception to the rule. Irish history has ever been written by the master class—in the interests of the master class.

Whenever the social question cropped up in modern Irish history, whenever the question of labor and its wrongs figured in the writings or speeches of our modern Irish politicians, it was simply that they might be used as weapons in the warfare against a political adversary, and not at all because the person so using them was personally convinced that the subjection of labor was in itself a wrong. This book is intended primarily to prove that contention. To prove it by a reference to the evidence—documentary and otherwise—adduced, illustrating the state of the Irish working class in the past, the almost total indifference of our Irish politicians to the sufferings of the mass of the people, and the true inwardness of many of the political agitations which have occupied the field in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Special attention is given to the period preceding the Union and evidence brought forward relative to the state of Ireland before and during the continuance of Grattan’s Parliament; to the condition of the working people in the town and country, and the attitude towards labor taken up by politicians of all sides, whether patriot or ministerialist. In other words, we propose to do what in us lies to repair the deliberate neglect of the social question by our historians; and to prepare the way in order that other and abler pens than our own may demonstrate to the reading public the manner in which economic conditions have controlled and dominated our Irish history.

But as a preliminary to this essay on our part it becomes necessary to recapitulate here some of the salient facts of history we have elsewhere insisted upon as essential to a thorough grasp of the “Irish Question.”

Politically, Ireland has been under the control of England for the past seven hundred years, during the greater part of which time the country has been the scene of constant wars against her rule upon the part of the native Irish. Until the year 1649, these wars were complicated by the fact that they were directed against both the political and social order recognized by the English invader. It may surprise many readers to learn that up to the date above mentioned, the basis of society in Ireland except within the Pale (a small strip of territory around the capital city, Dublin) rested upon communal or tribal ownership of land. The Irish chief, although recognized in the courts of France, Spain, and Rome as the peer of the reigning princes of Europe, in reality held his position upon the sufferance of his people, and as an administrator of the tribal affairs of his people, while the land or territory of the clan was entirely removed from his private jurisdiction. In the parts of Ireland where for four hundred years after the first conquest (so-called) the English governors could not penetrate except at the head of a powerful army, the social order which prevailed in England—feudalism—was unknown, and as this comprised the greater portion of the country, it gradually came to be understood that the war against the foreign oppressor was also a war against private property in land. But with the forcible breakup of the clan system in 1649, the social aspect of the Irish struggle sank out of sight, its place being usurped by the mere political expressions of the fight for freedom. Such an event was, of course, inevitable in any case. Communal ownership of land would undoubtedly have given way to the privately owned system of capitalist-landlordism, even if Ireland had remained an independent country, but coming as it did in obedience to the pressure of armed force from without, instead of by the operation of economic forces within, the change has been bitterly and justly resented by the vast mass of the Irish people, many of whom still mix with their dreams of liberty longings for a return to the ancient system of land tenure—now organically impossible. The dispersion of the clans, of course, put an end to the leadership of the chiefs, and in consequence, the Irish aristocracy being all of foreign or traitor origin, Irish patriotic movements fell entirely into the hands of the middle class, and became, for the most part, simply idealized expressions of middle-class interest.

Hence the spokesmen of the middle class, in the press and on the platform, have consistently sought the emasculation of the Irish national movement, the distortion of Irish history, and, above all, the denial of all relation between the social rights of the Irish toilers and the political rights of the Irish nation. It was hoped and intended by this means to create what is termed “a real national movement”—i.e., a movement in which each class would recognize the rights of other classes and, laying aside their contentions, would unite in a national struggle against the common enemy—England. Needless to say, the only class deceived by such phrases was the working class. When questions of “class” interests are eliminated from public controversy, a victory is thereby gained for the possessing, conservative class, whose only hope of security lies in such elimination. Like a fraudulent trustee, the bourgeois dreads nothing so much as an impartial and rigid inquiry into the validity of his title deeds. Hence the bourgeois press and politicians incessantly strive to inflame the working-class mind to fever heat upon questions outside the range of their own class interests. War, religion, race, language, political reform, patriotism—apart from whatever intrinsic merits they may possess—all serve in the hands of the possessing class as counter-irritants, whose function it is to avert the catastrophe of social revolution by engendering heat in such parts of the body politic as are the farthest removed from the seat of economic enquiry, and consequently of class consciousness on the part of the proletariat. The bourgeois Irishman has long been an adept at such maneuvering, and has, it must be confessed, found in his working-class countrymen exceedingly pliable material. During the last hundred years every generation in Ireland has witnessed an attempted rebellion against English rule. Every such conspiracy or rebellion has drawn the majority of its adherents from the lower orders in town and country; yet, under the inspiration of a few middle-class doctrinaires, the social question has been rigorously excluded from the field of action to be covered by the rebellion if successful; in hopes that by such exclusion it would be possible to conciliate the upper classes and enlist them in the struggle for freedom. The result has in nearly every case been the same. The workers, though furnishing the greatest proportion of recruits to the ranks of the revolutionists, and consequently of victims to the prison and the scaffold, could not be imbued en masse with the revolutionary fire necessary to seriously imperil a dominion rooted for seven hundred years in the heart of their country. They were all anxious enough for freedom but, realizing the enormous odds against them, and being explicitly told by their leaders that they must not expect any change in their condition of social subjection, even if successful, they as a body shrank from the contest, and left only the purest-minded and most chivalrous of their class to face the odds and glut the vengeance of the tyrant—a warning to those in all countries who neglect the vital truth that successful revolutions are not the product of our brains, but of ripe material conditions.

The upper class also turned a contemptuously deaf ear to the charming of the bourgeois patriot. They (the upper class) naturally clung to their property, landed and otherwise; under the protecting power of England they felt themselves secure in the possession thereof, but were by no means assured as to the fate which might befall it in a successful revolutionary uprising. The landlord class, therefore, remained resolutely loyal to England, and while the middle-class poets and romanticists were enthusing on the hope of a “union of class and creeds,” the aristocracy were pursuing their private interests against their tenants with a relentlessness which threatened to depopulate the country, and led even an English Conservative newspaper, the London Times, to declare that “the name of an Irish landlord stinks in the nostrils of Christendom.”

It is well to remember, as a warning against similar foolishness in future, that the generation of Irish landlords which had listened to the eloquent pleadings of Thomas Davis was the same as that which in the Famine years “exercised its rights with a rod of iron and renounced its duties with a front of brass.”

The lower middle class gave to the national cause in the past many unselfish patriots, but, on the whole, while willing and ready enough to please their humble fellow countrymen, and to compound with their own conscience by shouting louder than all others their untiring devotion to the cause of freedom, they, as a class, unceasingly strove to divert the public mind upon the lines of constitutional agitation for such reforms as might remove irritating and unnecessary officialism, while leaving untouched the basis of national and economic subjection. This policy enabled them to masquerade as patriots before the unthinking multitude, and at the same time lent greater force to their words when as “patriot leaders” they cried down any serious revolutionary movement that might demand from them greater proofs of sincerity than could be furnished by the strength of their lungs, or greater sacrifices than would be suitable to their exchequer. ’48 and ’67, the Young Ireland and the Fenian Movements, furnish the classic illustrations of this policy on the part of the Irish middle class.

Such, then, is our view of Irish politics and Irish history. Subsequent chapters will place before our readers the facts upon which such a view is based.

Chapter II. The Jacobites and the Irish People

If there was a time when it behoved men in public stations to be explicit, if ever there was a time when those scourges of the human race called politicians should lay aside their duplicity and finesse, it is the present moment. Be assured that the people of this country will no longer bear that their welfare should be the sport of a few family factions; be assured they are convinced their true interest consists in putting down men of self creation, who have no object in view but that of aggrandizing themselves and their families at the expense of the public, and in setting up men who shall represent the nation, who shall be accountable to the nation, and who shall do the business of the nation.

—Arthur O’Connor in Irish House of Commons, May 4, 1795

Modern Irish history, properly understood, may be said to start with the close of the Williamite Wars in the year 1691. All the political life of Ireland during the next two hundred years draws its coloring from, and can only be understood in the light of, that conflict between King James of England and William, Prince of Orange. Our Irish politics, even to this day and generation, have been and are largely determined by the light in which the different sections of the Irish people regarded the prolonged conflict which closed with the surrender of Sarsfield and the garrison of Limerick to the investing forces of the Williamite party. Yet never, in all the history of Ireland, has there been a war in which the people of Ireland had less reason to be interested either on one side or the other. It is unfortunately beyond all question that the Irish Catholics of that time did fight for King James like lions. It is beyond all question that the Irish Catholics shed their blood like water, and wasted their wealth like dirt, in an effort to retain King James upon the throne. But it is equally beyond all question that the whole struggle was no earthly concern of theirs; that King James was one of the most worthless representatives of a worthless race that ever sat upon a throne; that the “pious glorious and immortal” William was a mere adventurer fighting for his own hand, and his army recruited from the impecunious swordsmen of Europe who cared as little for Protestantism as they did for human life; and that neither army had the slightest claim to be considered as a patriot army combating for the freedom of the Irish race. So far from the paeans of praise lavished upon Sarsfield and the Jacobite army being justified, it is questionable whether a more enlightened or patriotic age than our own will not condemn them as little better than traitors for their action in seducing the Irish people from their allegiance to the cause of their country’s freedom, to plunge them into a war on behalf of a foreign tyrant—a tyrant who, even in the midst of their struggles on his behalf, opposed the Dublin Parliament in its efforts to annul the supremacy of the English Parliament. The war between William and James offered a splendid opportunity to the subject people of Ireland to make a bid for freedom while the forces of their oppressors were rent in a civil war. The opportunity was cast aside, and the subject people took sides on behalf of the opposing factions of their enemies. The reason is not hard to find. The Catholic gentlemen and nobles who had the leadership of the people of Ireland at the time were, one and all, men who possessed considerable property in the country, property to which they had, notwithstanding their Catholicity, no more right or title than the merest Cromwellian or Williamite adventurer. The lands they held were lands which in former times belonged to the Irish people—in other words, they were tribe lands. As such, the peasantry—then reduced to the position of mere tenants-at-will—were the rightful owners of the soil, whilst the Jacobite chivalry of King James were either the descendants of men who had obtained their property in some former confiscation as the spoils of conquest; of men who had taken sides with the oppressor against their own countrymen and were allowed to retain their property as the fruits of treason; or finally, of men who had consented to seek from the English government a grant giving them a personal title to the lands of their clansmen. For such a combination no really national action could be expected, and from first to last of their public proceedings they acted as an English faction, and as an English faction only. In whatever point they might disagree with the Williamites, they were at least in perfect accord with them on one point—viz., that the Irish people should be a subject people; and it will be readily understood that even had the war ended in the complete defeat of William and the triumph of James, the lot of the Irish, whether as tillers of the soil or as a nation, would not have been substantially improved. The undeniable patriotism of the rank and file does not alter the truthfulness of this analysis of the situation. They saw only the new enemy from England, the old English enemy settled in Ireland they were generously, but foolishly, ready to credit with all the virtues and attributes of patriotic Irishmen.

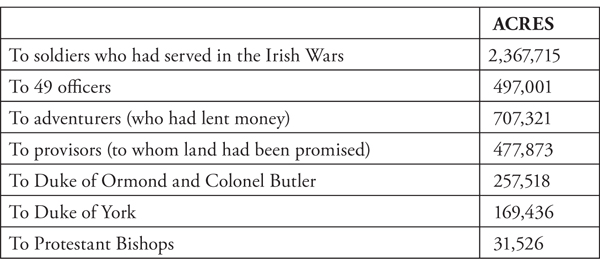

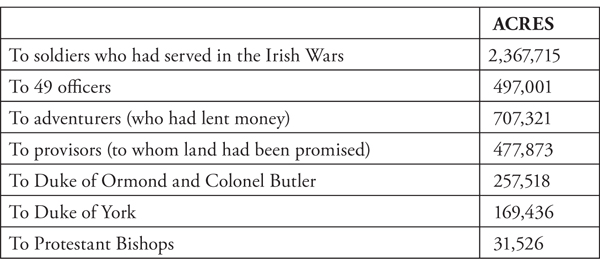

To further illustrate our point regarding the character of the Jacobite leaders in Ireland we might adduce the result of the great land settlement of Ireland in 1675. Eleven million acres had been surveyed at the time, of which four million acres were in the possession of Protestant settlers as the result of previous confiscations.

Lands so held were never disturbed, but the remainder were distributed as follows:

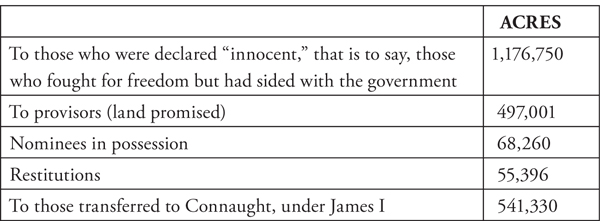

The lands left to the Catholics were distributed among the Catholic gentlemen as follows:

It will be thus seen that with the exception of the lands held in Connacht, all the lands held by the Catholic gentry throughout Ireland were lands gained in the manner we have before described—as spoils of conquest or the fruits of treachery. Even in that province the lands of the gentry were held under a feudal tenure from the English Crown, and therefore their owners had entered into a direct agreement with the invader to set aside the rights of the clan community in favor of their own personal claims. Here then was the real reason for the refusal of the Irish leaders of that time to raise the standard of the Irish nation instead of the banner of an English faction. They fought, not for freedom for Ireland, nor for the restitution of their rights to the Irish people, but rather to secure that the class who then enjoyed the privilege of robbing the Irish people should not be compelled to give way in their turn to a fresh horde of land thieves. Much has been made of their attempt to repeal Poyning’s Law[1] and in other ways to give greater legislative force to the resolutions of the Dublin Parliament, as if such acts were a proof of their sincere desire to free the country, and not merely to make certain their own tenure of power. But such claims, on the part of some writers, are only another proof of the difficulty of comprehending historical occurrences without having some central principle to guide and direct the task.

For the benefit of our readers we may here set forth the socialist key to the pages of history, in order that it may be the more readily understood why in the past the governing classes have ever and always aimed at the conquest of political power as the guarantee for their economic domination—or, to put it more plainly, for the social subjection of the masses—and why the freedom of the workers, even in a political sense, must be incomplete and insecure until they wrest from the governing classes the possession of the land and instruments of wealth production. This proposition, or key to history, as set forth by Karl Marx, the greatest of modern thinkers and first of scientific socialists, is as follows: “That in every historical epoch the prevailing method of economic production and exchange, and the social organization necessarily following from it, forms the basis upon which alone can be explained the political and intellectual history of that epoch.”

In Ireland at the time of the Williamite war, the “prevailing method of economic production and exchange” was the feudal method, based upon the private ownership of lands stolen from the Irish people, and all the political struggles of the period were built upon the material interests of one set of usurpers who wished to retain, and another set who wished to obtain, the mastery of those lands—in other words, the application of such a key as the above to the problem furnished by the Jacobite Parliament of King James, at once explains the reason of the so-called patriotic efforts of the Catholic gentry. Their efforts were directed to the conservation of their own rights of property, as against the right of the English Parliament to interfere with or regulate such rights. The so-called Patriot Parliament was in reality, like every other Parliament that ever sat in Dublin, merely a collection of land thieves and their lackeys; their patriotism consisted in an effort to retain for themselves the lands of the native peasantry; the English influence against which they protested was the influence of their fellow thieves in England, hungry for a share of the spoil; and Sarsfield and his followers did not become patriots because of their fight against King William’s government any more than an Irish Whig out of his office becomes a patriot because of his hatred to the Tories who are in. The forces which battled beneath the walls of Derry or Limerick were not the forces of England and Ireland, but the forces of two English political parties fighting for the possession of the powers of government; and the leaders of the Irish Wild Geese on the battlefield of Europe were not shedding their blood because of their fidelity to Ireland, as our historians pretend to believe, but because they had attached themselves to the defeated side in English politics. This fact was fully illustrated by the action of the old Franco-Irish at the time of the French Revolution. They in a body volunteered into the English army to help to put down the new French Republic, and as a result Europe witnessed the spectacle of the new republican Irish exiles fighting for the French Revolution, and the sons of the old aristocratic Irish exiles fighting under the banner of England to put down that Revolution. It is time we learned to appreciate and value the truth upon such matters, and to brush from our eyes the cobwebs woven across them by our ignorant or unscrupulous history-writing politicians.

On the other hand, it is just as necessary to remember that King William, when he had finally subdued his enemies in Ireland, showed by his actions that he and his followers were animated throughout by the same class feeling and considerations as their opponents. When the war was over, William confiscated a million and a half acres, and distributed them among the aristocratic plunderers who followed him, as follows:

He gave Lord Bentinck, 135,300 acres; Lord Albemarle, 103,603; Lord Coningsby, 59,667; Lord Romney, 49,517; Lord Galway, 36,142; Lord Athlone, 26,840; Lord Rochford, 49,512; Dr. Leslie, 16,000; Mr. F. Keighley, 12,000; Lord Mountjoy, 12,000; Sir T. Prendergast, 7,083; Colonel Hamilton, 5,886 acres.

These are a few of the men whose descendants some presumably sane Irishmen imagine will be converted into “nationalists” by preaching “a union of classes.”

It must not be forgotten, also, if only as proof of his religious sincerity, that King William bestowed 95,000 acres, plundered from the Irish people, upon his paramour, Elizabeth Villiers, Countess of Orkney. But the virtuous Irish Parliament interfered, took back the land, and distributed it amongst their immediate friends, the Irish Loyalist adventurers.

Chapter III. Peasant Rebellions

To permit a small class, whether alien or native, to obtain a monopoly of the land is an intolerable injustice; its continued enforcement is neither more nor less a robbery of the hard and laborious earnings of the poor.

—Irish People (organ of the Fenian Brotherhood), July 30, 1864

In the preceding chapter we pointed out that the Williamite war in Ireland, from Derry to Limerick, was primarily a war for mastery over the Irish people, and that all questions of national or industrial freedom were ignored by the leaders on both sides as being presumably what their modern prototypes would style “beyond the pale of practical politics.”

When the nation had once more settled down to the pursuits of peace, and all fear of a Catholic or Jacobite rising had departed from the minds of even the most timorous squireen, the unfortunate tenantry of Ireland, whether Catholic or Protestant, were enlightened upon how little difference the war had made to their position as a subject class. The Catholic who had been so foolish as to adhere to the army of James could not, in the nature of things, expect much consideration from his conquerors—and he received none—but he had the consolation of seeing that the rank and file of his Protestant enemies were treated little, if at all, better than himself. When the hungry horde of adventurers who had brought companies to the service of William had glutted themselves with the plunder for which they had crossed the Channel, they showed no more disposition to remember the claims of the common soldier—by the aid of whose sword they had climbed to power—than do our present rulers when they consign to the workhouse the shattered frames of the poor fools who, with murder and pillage, have won for their masters empire in India or Africa.

Before long the Protestant and Catholic tenants were suffering one common oppression. The question of political supremacy having been finally decided, the yoke of economic slavery was now laid unsparingly upon the backs of the laboring people. All religious sects suffered equally from this cause. The Penal Laws then in operation against the Catholics did indeed make the life of the propertied Catholics more insecure than would otherwise have been the case; but to the vast mass of the population the misery and hardship entailed by the working out of economic laws were fraught with infinitely more suffering than it was at any time within the power of the Penal Laws to inflict. As a matter of fact, the effect of the latter code in impoverishing wealthy Catholics has been much overrated. The class interests, which at all times unite the propertied section of the community, operated, to a large extent, to render impossible the application of the power of persecution to its full legal limits. Rich Catholics were quietly tolerated, and generally received from the rich Protestants an amount of respect and forbearance which the latter would not at any time extend to their Protestant tenantry or work-people. So far was this true that, like the Jew, some Catholics became notorious as moneylenders, and in the year 1763 a bill was introduced into the Irish House of Commons to give greater facilities to Protestants wishing to borrow money from Catholics. The bill proposed to enable Catholics to become mortgagees of the landed estates in order that Protestants wishing to borrow money could give a mortgage upon their lands as security to the Catholic lender. The bill was defeated, but its introduction serves to show how little the Penal Laws had operated to prevent the accumulation of wealth by the Catholic propertied classes.

But the social system thus firmly rooted in the soil of Ireland—and accepted as righteous by the ruling class irrespective of religion—was a greater enemy to the prosperity and happiness of the people than any legislation religious bigotry could devise. Modern Irish politicians, inspired either by a blissful unconsciousness of the facts of history, or else sublimely indifferent to its teachings, are in the habit of tracing the misery of Ireland to the Legislative Union as its source, but the slightest possible acquaintance with ante-Union literature will reveal a record of famine, oppression, and injustice, due to economic causes, unsurpassed at any other stage of modern Irish history. Thus Dean Swift, writing in 1729, in that masterpiece of sarcasm entitled “A Modest Proposal for Preventing the Children of the Poor People in Ireland from Becoming a Burden on Their Parents or Country, and for Making Them Beneficial to the Public,” was so moved by the spectacle of poverty and wretchedness that, although having no love for the people, for whom, indeed, he had no better name than “the savage old Irish,” he produced the most vehement and bitter indictment of the society of his day, and the most striking picture of hopeless despair, that literature has yet revealed. Here is in effect his proposal:

It is a melancholy object to those who walk through this great town, or travel in the country, when they see the streets, the roads, and cabin doors crowded with beggars of the female sex, followed by three, four, or six children all in rags, and importuning every passenger for an alms…. I, do, therefore, offer it to public consideration that of the hundred and twenty thousand children already computed, twenty thousand may be reserved for breed…. that the remaining hundred thousand may at a year old be offered in sale to the persons of quality and fortune through the kingdom, always advising the mother to let them suck plentifully in the last month so as to render them plump and fat for a good table. A child will make two dishes at an entertainment for friends, and when the family dines alone the fore or hind quarters will make a reasonable dish, and seasoned with a little pepper or salt, will be very good boiled on the fourth day, especially in winter…. I have already computed the charge of nursing a beggar’s child (in which list I reckon all cottagers, laborers, and four-fifths of the farmers), to be about two shillings per annum, rags included; and I believe no gentleman would refuse to give ten shillings for the carcase of a good, fat child, which, as I have said, will make four dishes of excellent, nutritious meat.

Sarcasm, truly, but how terrible must have been the misery which made even such sarcasm permissible! Great as it undoubtedly was, it was surpassed twelve years later in the famine of 1740, when no less a number than four hundred thousand are estimated to have perished of hunger or of the diseases which follow in the wake of hunger. This may seem an exaggeration, but the statement is amply borne out by contemporary evidence. Thus Bishop Berkeley, of the Anglican Church, writing to Mr. Thomas Prior, of Dublin, in 1741, mentions that “the other day I heard one from the county of Limerick say that whole villages were entirely dispeopled. About two months since I heard Sir Richard Cox say that five hundred were dead in the parish, though in a country, I believe, not very populous.” And a pamphlet entitled The Groans of Ireland, published in 1741, asserts, “The universal scarcity was followed by fluxes and malignant fevers, which swept off multitudes of all sorts, so that whole villages were laid waste.”

This famine, be it remarked, like all modern famine, was solely attributable to economic causes; the poor of all religions and politics were equally sufferers; the rich of all religions and politics were equally exempt. It is also noteworthy, as illustrating the manner in which the hireling scribes of the propertied classes have written history, while a voluminous literature has arisen round the Penal Laws—a subject of merely posthumous interest—a matter of such overwhelming importance, both historically and practically, as the predisposing causes of Irish famine can, as yet, claim no notice except scanty and unavoidable references in national history.

The country had not recovered from the direful effects of this famine when a further economic development once more plunged the inhabitants into blackest despair. Disease having attacked and destroyed great quantities of cattle in England, the aristocratic rulers of that country—fearful lest the ensuing high price of meat should lead to a demand for higher wages on the part of the working class in England—removed the embargo off Irish cattle, meat, butter, and cheese at the English ports, thus partly establishing free trade in those articles between the two countries. The immediate result was that all such provisions brought such a price in England that tillage farming in Ireland became unprofitable by comparison, and every effort was accordingly made to transform arable lands into sheep-walks or grazing lands. The landlord class commenced evicting their tenants; breaking up small farms, and even seizing upon village common lands and pasture grounds all over the country with the most disastrous results to the laboring people and cottiers generally. Where a hundred families had reaped as sustenance from their small farms, or by hiring out their labor to the owners of large farms, a dozen shepherds now occupied their places. Immediately there sprung up throughout Ireland numbers of secret societies in which the dispossessed people strove by lawless acts and violent methods to restrain the greed of their masters, and to enforce their own right to life. They met in large bodies, generally at midnight, and proceeded to tear down enclosures; to hough cattle; to dig up and so render useless the pasture lands; to burn the houses of the shepherds; and in short, to terrorize their social rulers into abandoning the policy of grazing in favor of tillage, and to give more employment to the laborers and more security to the cottier. These secret organizations assumed different names and frequently adopted different methods, and it is now impossible to tell whether they possessed any coherent organization or not. Throughout the South they were called Whiteboys, from the practice of wearing white shirts over their clothes when on their nocturnal expeditions. About the year 1762 they posted their notices on conspicuous places in the country districts—notably, Cork, Waterford, Limerick, and Tipperary—threatening vengeance against such persons as had incurred their displeasure as graziers, evicting landlords, etc.

These proclamations were signed by an imaginary female, sometimes called the “Sive Oultagh”’ sometimes “Queen Sive,” sometimes they were in the name of “Queen Sive and Her Subjects.” Government warred upon these poor wretches in the most vindictive manner: hanging, shooting, transporting without mercy; raiding villages at dead of night for suspected Whiteboys, and dragging the poor creatures before magistrates who never condescended to hear any evidence in favor of the prisoners, but condemned them to whatever punishments their vindictive class spirit or impaired digestion might prompt.

The spirit of the ruling class against those poor slaves in revolt may be judged by two incidents exemplifying how Catholic and Protestant proprietors united to fortify injustice and preserve their privileges, even at a time when we have been led to believe that the Penal Laws formed an insuperable barrier against such Union. In the year 1762 the government offered the sum of £100 for the capture of the first five Whiteboy chiefs. The Protestant inhabitants of the city of Cork offered in addition £300 for the chief, and £50 for each of his first five accomplices arrested. Immediately the wealthy Catholics of the same city added to the above sums a promise of £200 for the chief and £40 for each of his first five subordinates. This was at a time when an English governor, Lord Chesterfield, declared that if the military had killed half as many landlords as they did Whiteboys, they would have contributed more effectually to restore quiet, a remark which conveys some slight idea of the carnage made among the peasantry. Yet, Flood, the great Protestant “patriot,” he of whom Davis sings,

Bless Harry Flood, who nobly stood

By us through gloomy years.

in the Irish House of Commons of 1763 fiercely denounced the government for not killing enough of the Whiteboys. He had called it “clemency.”

Chapter IV. Social Revolts and Political Kites and Crows

When the aristocracy come forward the people fall backward; when the people come forward the aristocracy, fearful of being left behind, insinuate themselves into our ranks and rise into timid leaders of treacherous auxiliaries.

—Secret Manifesto of Projectors of United Irish Society, 1791

In the north of Ireland the secret organizations of the peasantry were known variously as Oakboys and the Hearts of Steel or Steelboys. The former directed their efforts mainly against the system of compulsory road repairing, by which they were required to contribute their unpaid labor for the upkeep of the county roads; a system, needless to say, offering every opportunity to the county gentry to secure labor gratuitously for the embellishment of their estates and private roads on the pretext of serving public ends. The Oakboy organization was particularly strong in the counties of Monaghan, Armagh, and Tyrone. In a pamphlet published about the year 1762, an account is given of a “rising”’ of the peasantry in the first-named county and of the heroic exploits of the officer in command of the troops engaged in suppressing said rising, in a manner which irresistibly recalls the present accounts in the English newspapers of the punitive expeditions of the British army against the “marauding” hill tribes of India or Dacoits of Burmah. The work is entitled the “True and Faithful Account of the Late Insurrections in the North, with a Narrative of Colonel Coote’s Campaign amongst the Oakboys in County Monaghan,” etc. The historian tells how, on hearing of the “rising,” the brave British officer set off with his men to the town of Castleblayney; how on his way thither he passed numerous bodies of the peasantry proceeding in the same direction, each with an oak bough or twig stuck in his hat as a sign of his treasonable sympathies; how on entering Castleblayney he warned the people to disperse, and only received defiant replies, and even hostile manifestations; how he then took refuge in the Market House and prepared to defend it if need be; and how, after occupying that stronghold all night, he found the next morning the rebels had withdrawn from the town. Next, there is an account of the same valiant general’s entry into the town of Ballybay. Here he found all the houses shut against him, each house proudly displaying an oak bough in its windows and all the people seemingly prepared to resist to the uttermost. Apparently determined to make an example, and so to strike terror, the valiant soldier and his men proceeded to arrest the ringleader, and, after a severe struggle, did succeed in breaking into some of the cabins of the poor people, and arresting some person, who was accordingly hauled off to the town of Monaghan, there to be dealt with according to the forms of the law from which every consideration of justice was rigorously excluded. In the town of Clones, we are informed, the people withstood the royal forces in the marketplace, but were, of course, defeated. The Monaghan Oakboys were then driven across the borders of their own county into Armagh, where they made a last stand, but were attacked and defeated in a “pitched battle,” the severity of which may be gauged from the fact that no casualties were reported on the side of the troops.

But the general feeling of the people was so pronouncedly against the system of compulsory and unpaid labor on the roads the government subsequently abolished the practice, and instituted a road rate providing for payment for such necessary labor by a tax upon owners and occupiers of property in the district. Needless to say, the poor peasants who were suffering martyrdom in prison for their efforts to remedy what the government had by such remedial legislation admitted to be an injustice, were left to rot in their cells—the usual fate of pioneers of reform.

The Steelboys were a more formidable organization, and had their strongholds in the counties of Down and Antrim. They were for the most part Presbyterian or other dissenters from the Established Church, and, like the Whiteboys, aimed at the abolition or reduction of tithes and the restriction of the system of consolidating farms for grazing purposes. They frequently appeared in arms, and moved with a certain degree of discipline, coming together from widely separated parts in obedience, apparently, to the orders of a common center. In the year 1722, six of their number were arrested and lodged in the town jail of Belfast. Their associates immediately mustered in thousands, and in the open day marched upon that city, made themselves masters thereof, stormed the jail, and released their comrades. This daring action excited consternation in the ranks of the governing classes, troops were despatched to the spot, and every precaution taken to secure the arrest of the leaders. Out of the numerous prisoners made, a batch were selected for trial, but whether as a result of intimidation or because of their sympathy with the prisoners it is difficult to tell, the jury in Belfast refused to convict, and when the trial was changed to Dublin, the government was equally unfortunate. The refusal of the juries to convict was probably in a large measure due to the unpopularity of the act then just introduced to enable the government to put persons accused of agrarian offenses on trial in a different county to their own. When this act was repealed the convictions and executions went on as merrily as before. Many a peasant’s corpse swung on the gibbet, and many a promising life was doomed to blight and decay in the foul confines of the prison hell, to glut the vengeance of the dominant classes. Arthur Young, in his Tour of Ireland, thus describes the state of matters against which those poor peasants revolted.

A landlord in Ireland can scarcely invent an order which a servant, laborer, or cottier dares to refuse to execute…. Disrespect, or anything tending towards sauciness he may punish with his cane or his horsewhip with the most perfect security. A poor man would have his bones broken if he offered to lift a hand in his own defense…. Landlords of consequence have assured me that many of their cottiers would think themselves honored by having their wives and daughters sent for to the bed of their master—a mark of slavery which proves the oppression under which people must live.

It will be observed by the attentive student that the “patriots” who occupied the public stage in Ireland during the period we have been dealing with never once raised their voices in protest against such social injustice. Like their imitators today, they regarded the misery of the Irish people as a convenient handle for political agitation; and, like their imitators today, they were ever ready to outvie even the government in their denunciation of all those who, more earnest than themselves, sought to find a radical cure for such misery.

Of the trio of patriots—Swift, Molyneux, and Lucas—it may be noted that their fight was simply a repetition of the fight waged by Sarsfield and his followers in their day—a change of persons and of stage costume truly, but no change of character; a battle between the kites and the crows.

They found themselves members of a privileged class, living upon the plunder of the Irish people; but early perceived, to their dismay, that they could not maintain their position as a privileged class without the aid of the English Army; and in return for supplying that army the English ruling class were determined to have the lion’s share of the plunder. The Irish Parliament was essentially an English institution; nothing like it existed before the Norman Conquest. In that respect it was on the same footing as landlordism, capitalism, and their natural-born child—pauperism. England sent a swarm of adventurers to conquer Ireland; having partly succeeded, these adventurers established a Parliament to settle disputes among themselves, to contrive measures for robbing the natives, and to prevent their fellow tyrants who had stayed in England from claiming the spoil. But in course of time the section of land thieves resident in England did claim a right to supervise the doings of the adventurers in Ireland, and consequently to control their Parliament. Hence arose Poyning’s Law, and the subordination of Dublin Parliament to London Parliament. Finding this subordinate position of the Parliament enabled the English ruling class to strip the Irish workers of the fruits of their toil, the more far-seeing of the privileged class in Ireland became alarmed lest the stripping process should go too far, and leave nothing for them to fatten upon.

At once they became patriots, anxious that Ireland—which, in their phraseology, meant the ruling class in Ireland—should be free from the control of the Parliament of England. Their pamphlets, speeches, and all public pronouncements were devoted to telling the world how much nicer, equitable, and altogether more delectable it would be for the Irish people to be robbed in the interests of a native-born aristocracy than to witness the painful spectacle of that aristocracy being compelled to divide the plunder with its English rival. Perhaps Swift, Molyneux, or Lucas did not confess even to themselves that such was the basis of their political creed. The human race has at all times shown a proneness to gloss over its basest actions with a multitude of specious pretenses, and to cover even its iniquities with the glamor of a false sentimentality. But we are not dealing with appearances but realities, and, in justice to ourselves, we must expose the flimsy sophistry which strives to impart to a sordid, self-seeking struggle the appearance of a patriotic movement. In opposition to the movements of the people, the patriot politicians and government alike were an undivided mass.

In their fight against the tithes the Munster peasantry, in 1786, issued a remarkable document, which we here reprinted as an illustration of the thought of the people of the provinces of that time. This document was copied into many papers at the time, and was also reprinted as a pamphlet in October of that year.

LETTER ADDRESSED TO THE MUNSTER PEASANTRY

To obviate the bad impression made by the calumnies of our enemies, we beg leave to submit to you our claim for the protection of a humane gentry and humbly solicit yours, if said claim shall appear to you founded in justice and good policy.

In every age, country, and religion the priesthood are allowed to have been artful, usurping, and tenacious of their ill-acquired prerogatives. Often have their jarring interests and opinions deluged with Christian blood this long-devoted isle.

Some thirty years ago our unhappy fathers—galled beyond human sufferance—like a captive lion vainly struggling in the toils, strove violently to snap their bonds asunder, but instead rivetted them more tight. Exhausted by the bloody struggle, the poor of this province submitted to their oppression, and fattened with their vitals each decimating leech.

The luxurious parson drowned in the riot of his table the bitter groans of those wretches that his proctor fleeced, and the poor remnant of the proctor’s rapine was sure to be gleaned by the rapacious priest; but it was blasphemy to complain of him; Heaven, we thought, would wing its lightning to blast the wretch who grudged the Holy Father’s share. Thus plundered by either clergy, we had reason to wish for our simple Druids again.

At last, however, it pleased pitying Heaven to dispel the murky cloud of bigotry that hovered over us so long. Liberality shot her cheering rays, and enlightened the peasant’s hovel as well as the splendid hall. O’Leary told us, plain as friar could, that a God of a universal love would not confine His salvation to one sect alone, and that the subject’s election was the best title to the crown.

Thus improved in our religion and our politics … we resolve to evince on every occasion the change in our sentiments and hope to succeed in our sincere attempts. We examined the double causes of our grievances, and debated long how to get them removed, until at length our resolves terminated in this general peaceful remonstrance.

Humanity, justice, and policy enforce our request. Whilst the tithe farmer enjoys the fruit of our labours, agriculture must decrease, and while the griping priest insists on more for the bridegroom than he is worth, population must be retarded.

Let the legislature befriend us now, and we are theirs forever. Our sincerity in the warmth of our attachment when once professed was never questioned, and we are bold to say no such imputation will ever fall on the Munster peasantry.

At a very numerous and peaceable meeting of the delegates of the Munster peasantry, held on Thursday, the 1st day of July, 1786, the following resolutions were unanimously agreed to, viz.:—

Resolved—That we will continue to oppose our oppressors by the most justifiable means in our power, either until they are glutted with our blood or until humanity raises her angry voice in the councils of the nation to protect the toiling peasant and lighten his burden.

Resolved—That the fickleness of the multitude makes it necessary for all and each of us to swear not to pay voluntarily priest or parson more than as follows:—

Potatoes, first crop, 6s. per acre; do., second crop, 4s.; wheat, 4s.; barley, 4s.; oats, 3s.; meadowing, 2s. 8d.; marriage, 5s.; baptism, 1s. 6d.; each family confession, 2s.; Parish Priest’s Sun. Mass, 1s.; any other, 1s. Extreme Unction, 1s.

Signed by order,

WILLIAM O’DRISCOL,

General to the Munster Peasantry

Chapter V. Grattan’s Parliament

Dynasties and thrones are not half so important as workshops, farms and factories. Rather we may say that dynasties and thrones, and even provisional governments, are good for anything exactly in proportion as they secure fair play, justice and freedom to those who labor.

—John Mitchel, 1848

We now come to the period of the Volunteers. In this year, 1778, the people of Belfast, alarmed by rumors of intended descents of French privateers, sent to the Irish secretary of state at Dublin Castle asking for a military force to protect their town. But the English Army had long been drafted off to the United States—then rebel American colonies of England—and Ireland was practically denuded of troops. Dublin Castle answered Belfast in the famous letter which stated that the only force available for the North would be “a troop or two of horse, or part of a company of invalids.”

On receipt of this news, the people began arming themselves and publicly organizing Volunteer corps throughout the country. In a short time Ireland possessed an army of some eighty thousand citizen soldiers, equipped with all the appurtenances of war; drilled, organized, and in every way equal to any force at the command of a regular government. All the expenses of the embodiment of this Volunteer army were paid by subscriptions of private individuals. As soon as the first alarm of foreign invasion had passed, the Volunteers turned their attention to home affairs and began formulating certain demands for reform—demands which the government was not strong enough to resist. Eventually, after a few years’ agitation on the Volunteer side, met by intrigue on the part of the government, the “patriot” party, led by Grattan and Flood, and supported by the moral (?) pressure of a Volunteer review outside the walls of the Parliament House, succeeded in obtaining from the legislature a temporary abandonment of the claim set up by the English Parliament to force laws upon the assembly at College Green. This and the concession of free trade (enabling Irish merchants to trade on equal terms with their English rivals) inaugurated what is known in Irish history as Grattan’s Parliament. At the present day our political agitators never tire of telling us with the most painful iteration that the period covered by Grattan’s Parliament was a period of unexampled prosperity for Ireland, and that, therefore, we may expect a renewal of this same happy state with a return of our “native legislature,” as they somewhat facetiously style that abortive product of political intrigue—Home Rule.

We might, if we choose, make a point against our political historians by pointing out that prosperity such as they speak of is purely capitalistic prosperity—that is to say, prosperity gauged merely by the volume of wealth produced, and entirely ignoring the manner in which the wealth is distributed amongst the workers who produce it. Thus in a previous chapter we quoted a manifesto issued by the Munster Peasantry in 1786 in which—four years after Grattan’s Parliament had been established—they called upon the legislature to help them, and resolved if such help was not forthcoming—and it was not forthcoming—to “resist our oppressors until they are glutted with our blood,” an expression which would seem to indicate that the “prosperity” of Grattan’s Parliament had not penetrated far into Munster. In the year 1794 a pamphlet published at 7 Capel Street, Dublin, stated that the average wage of a day laborer in the County Meath reached only 6d. per day in summer, and 4d. per day in winter; and in the pages of the Dublin Journal, a ministerial organ, and the Dublin Evening Post, a supporter of Grattan’s Party, for the month of April, 1796, there is to be found an advertisement of a charity sermon to be preached in the Parish Chapel, Meath Street, Dublin, in which advertisement there occurs the statement that in three streets of the Parish of St. Catherine’s “no less than 2,000 souls had been found in a starving condition.” Evidently, “‘prosperity” had not much meaning to the people of St. Catherine’s.

But this is not the ground we mean at present to take up. We will rather admit, for the purpose of our argument, that the Home Rule capitalistic definition of “prosperity” is the correct one, and that Ireland was prosperous under Grattan’s Parliament, but we must emphatically deny that such prosperity was in any but an infinitesimal degree produced by Parliament. Here again the socialist philosophy of history provides the key to the problem—points to the economic development as the true solution. The sudden advance of trade in the period in question was almost solely due to the introduction of mechanical power, and the consequent cheapening of manufactured goods. It was the era of the Industrial Revolution, when the domestic industries we had inherited from the Middle Ages were finally replaced by the factory system of modern times. The warping frame, invented by Arkwright in 1769; the spinning jenny, patented by Hargreaves in 1770; Crampton’s mechanical mule, introduced in 1779; and the application in 1778 of the steam engine to blast furnaces all combined to cheapen the cost of production, and so to lower the price of goods in the various industries affected. This brought into the field fresh hosts of customers, and so gave an immense impetus to trade in general in Great Britain as well as in Ireland. Between 1782 and 1804 the cotton trade more than trebled its total output; between 1783 and 1796 the linen trade increased nearly threefold; in the eight years between 1788 and 1796 the iron trade doubled in volume. The latter trade did not long survive this burst of prosperity. The invention of smelting by coal instead of wood in 1750, and the application of steam to blast furnaces, already spoken of, placed the Irish manufacturer at an enormous disadvantage in dealing with his English rival, but in the halycon days of brisk trade—between 1780 and 1800—this was not very acutely felt. But, when trade once more assumed its normal aspect of keen competition, Irish manufacturers, without a native coal supply and almost entirely dependent on imported English coal, found it impossible to compete with their trade rivals in the sister country who, with abundant supplies of coal at their own door, found it very easy, before the days of railways, to undersell and ruin the unfortunate Irish. The same fate, and for the same reason, befell the other important Irish trades. The period marked politically by Grattan’s Parliament was a period of commercial inflation due to the introduction of mechanical improvements into the staple industries of the country. As long as such machinery was worked by hand, Ireland could hold her place on the markets, but with this application of steam to the service of industry, which began on a small scale in 1785, and the introduction of the power loom, which first came into general use about 1813, the immense natural advantage of an indigenous coal supply finally settled the contest in favor of English manufacturers.

A native Parliament might have hindered the subsequent decay, as an alien Parliament may have hastened it; but in either case, under capitalistic conditions, the process itself was as inevitable as the economic evolution of which it was one of the most significant signs. How little Parliament had to do with it may be gauged by comparing the positions of Ireland and Scotland. In the year 1799, Mr. Foster in the Irish Parliament stated that the production of linen was twice as great in Ireland as in Scotland. The actual figures given were for the year 1796: 23,000,000 yards for Scotland as against 46,705,319 for Ireland. This discrepancy in favor of Ireland he attributed to the native Parliament. But by the year 1830, according to McCulloch’s Commercial Dictionary, the one port of Dundee in Scotland exported more linen than all Ireland. Both countries had been deprived of self-government. Why had Scottish manufacture advanced whilst that of Ireland had decayed? Because Scotland possessed a native coal supply, and every facility for industrial pursuits which Ireland lacked.

The “prosperity” of Ireland under Grattan’s Parliament was almost as little due to that Parliament as the dust caused by the revolutions of the coach wheel was due to the presence of the fly who, sitting on the coach, viewed the dust, and fancied himself the author thereof. And, therefore, true prosperity cannot be brought to Ireland except by measures somewhat more drastic than that Parliament ever imagined.

Chapter VI. Capitalist Betrayal of the Irish Volunteers

Remember still, through good and ill, How vain were prayers and tears. How vain were words till flashed the swords Of the Irish Volunteers.

—Thomas Davis

The theory that the fleeting “prosperity” of Ireland in the time we refer to was caused by the Parliament of Grattan is only useful to its propagators as a prop to their argument that the Legislative Union between Great Britain and Ireland destroyed the trade of the latter country, and that, therefore, the repeal of that Union placed all manufactures on a paying basis. The fact that the Union placed all Irish manufactures upon an absolutely equal basis legally with the manufactures of England is usually ignored, or, worse still, is so perverted in its statement as to leave the impression that the reverse is the case. In fact many thousands of our countrymen still believe that English laws prohibit mining in Ireland after certain minerals, and the manufacture of certain articles.

A moment’s reflection should remove such an idea. An English capitalist will cheerfully invest his money in Timbuctoo or China, or Russia, or anywhere that he thinks he can secure a profit, even though it may be in the territory of his mortal enemy. He does not invest his money in order to give employment to his workers, but to make a profit, and hence it would be foolish to expect that he would allow his Parliament to make laws prohibiting him from opening mines or factories in Ireland to make a profit out of the Irish workers. And there are not, and have not been since the Union, any such laws.

If a student desires to continue the study of this remarkable controversy in Irish history, and to compare this Parliamentarian theory of Irish industrial decline with that we have just advanced—the socialist theory outlined in our previous chapter—he has an easy and effective course to pursue in order to bring this matter to the test. Let him single out the most prominent exponents of Parliamentarianism and propound the following question:

Please explain the process by which the removal of Parliament from Dublin to London—a removal absolutely unaccompanied by any legislative interference with Irish industry—prevented the Irish capitalistic class from continuing to produce goods for the Irish market?

He will get no logical answer to his question—no answer that any reputable thinker on economic questions would accept for one moment. He will instead undoubtedly be treated to a long enumeration of the number of tradesmen and laborers employed at manufacturers in Ireland before the Union, and the number employed at some specific period, twenty or thirty years afterwards. This was the method adopted by Daniel O’Connell, the Liberator, in his first great speech in which he began his Repeal agitation, and has been slavishly copied and popularized by all his imitators since. But neither O’Connell nor any of his imitators have ever yet attempted to analyze and explain the process by which those industries were destroyed. The nearest approach to such an explanation ever essayed is the statement that the Union led to absentee landlordism and the withdrawal of the custom of these absentees from Irish manufacturers. Such an explanation is simply no explanation at all. It is worse than childish. Who would seriously contend that the loss of a few thousand aristocratic clients killed, for instance, the leather industry, once so flourishing in Ireland and now scarcely existent? The district in the city of Dublin which lies between Thomas Street and the South Circular Road was once a busy hive of men engaging in the tanning of leather and all its allied trades. Now that trade has almost entirely disappeared from this district. Were the members of Irish Parliament and the Irish landlords the only wearers of shoes in Ireland?—the only persons for whose use leather was tanned and manufactured? If not, how did their emigration to England make it impossible for the Irish manufacturer to produce shoes or harness for the millions of people still left in the country after the Union? The same remark applies to the weavers, once so flourishing a body in the same district, to the woollen trade, to the fishing trade, and so down along the line. The people of Ireland still wanted all these necessaries of life after the Union just as much as before, yet the superficial historian tells us that the Irish manufacturer was unable to cater to their demand, and went out of business accordingly. Well, we Irish are credited with being gifted with a strong sense of humor, but one is almost inclined to doubt it in the face of gravity with which the Parliamentary theory has been accepted by the masses of the Irish people.