PART 2

Introducing a Roommate

New Characters and Words

Study the six characters below and the common words written with them, paying careful attention to each character’s pronunciation, meaning, and structure, as well as similar-looking characters. After you’ve studied a character, turn to the Practice Book volume and practice writing it on the practice sheet, making sure to follow the correct stroke order and direction as you pronounce it out loud and think of its meaning.

79 |

的 |

-de |

(indicates possession) |

Radical is 白 bái “white.” The other component is 勺 sháo “spoon.” |

|||

的 |

-de |

(indicates possession) [P] |

|

我的名字 |

wŏde míngzi |

my name |

|

她的同屋 |

tāde tóngwū |

her roommate |

|

80 |

同 |

tóng |

same |

Radical is 口 kŏu “mouth.” The other components are 一 yī and 冂 jiōng “wide.” Perhaps this mnemonic will help you remember the character 同: “one” and the “same” “person” (represented by his/her 口 “mouth”) in a “wide” space. 同 is itself a phonetic in 铜 ( 銅 ) tóng “copper,” 筒 tŏng as in 筒子 tŏngzi “tube”, and 洞 dòng “hole.” Contrast 同 with 问 ( 問 ) wèn (75) and 国 ( 國 ) guó (74). |

|||

81 |

屋 |

wū |

room |

Radical is 尸 shī “corpse” [BF]. The other element is 至 zhì “arrive” [BF]. Here’s a macabre explanation of 屋 that you’ll be sure to remember: the “corpse” “arrives” in the “room.” |

|||

同屋 |

tóngwū |

roommate [N] |

|

82 |

别(別) |

bié |

don’t |

Radical is 刀 dāo “knife,” which is written 刂 when occurring at the right-hand side of a character. This radical is referred to colloquially as 立刀 lìdāo “standing knife.” The other component of the simplified character is 另 lìng “another.” Notice the small difference and (on the character practice sheets in Practice Book) the different stroke order between the simplified and traditional characters for this word; however, many native writers of Chinese don’t pay attention to such details. |

|||

别 ( 別 ) |

bié |

don’t [AV] |

|

83 |

名 |

míng |

name |

Radical is 口 kŏu “mouth.” This radical is referred to colloquially as 口字底 kŏuzìdĭ “bottom made up of the character 口.” The other part is 夕 xī “evening” [BF]. The idea is that in the “evening,” everyone should call out (with their “mouths”) their “names,” so that others might know who approaches. |

|||

84 |

字 |

zì |

Chinese character |

Radical is 宀 mián “roof” [BF]. This radical is referred to colloquially as 宝盖头 ( 寶蓋頭 ) băogàitóu “top made up of a canopy.” Phonetic is 子 zĭ “son” [BF]. To the ancient Chinese, “characters” were as precious as a “son” under a “roof.” |

|||

名字 |

míngzi |

name [N] |

|

New Words in BMC–SL 2-2 Written with Characters You Already Know

好 |

hăo |

“all right,” “O.K.” [IE] |

叫 |

jiào |

call someone a name [V] |

Reading Exercises (Simplified Characters)

Now practice reading the new characters and words for this lesson in context. Be sure to refer to the Notes at the end of this lesson, and make use of the accompanying audio disc to hear and practice correct pronunciation, phrasing, and intonation.

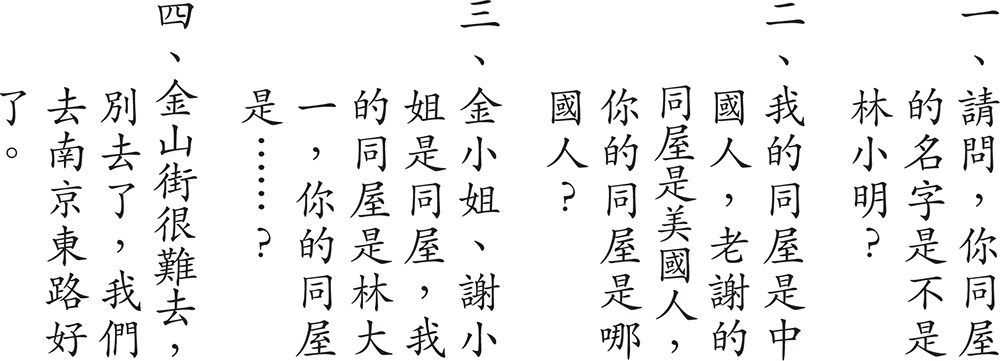

A. SENTENCES

Read out loud each of the following sentences, which include all the new characters of this lesson. The first time you read a sentence, focus special attention on the characters and words that are new to you, reminding yourself of their pronunciation and meaning. The second time, aim to comprehend the overall meaning of the sentence.

一、 |

请问,你同屋的名字是不是林小明? |

二、 |

我的同屋是中国人,老谢的同屋是美国人,你的同屋是哪国人? |

三、 |

金小姐、谢小姐是同屋,我的同屋是林大一,你的同屋是⋯⋯? |

四、 |

金山街很难去,别去了,我们去南京东路好了。 |

五、 |

她叫金香川。她的名字很难叫! |

六、 |

老林,你别走,你先请坐。 |

七、 |

请你别叫我王先生,叫我京生好了。 |

八、 |

你别去台北。谢小姐、李小姐她们都很忙。 |

九、 |

台湾是不是中国的一省? |

十、 |

“王大海”是中国人的名字吗? |

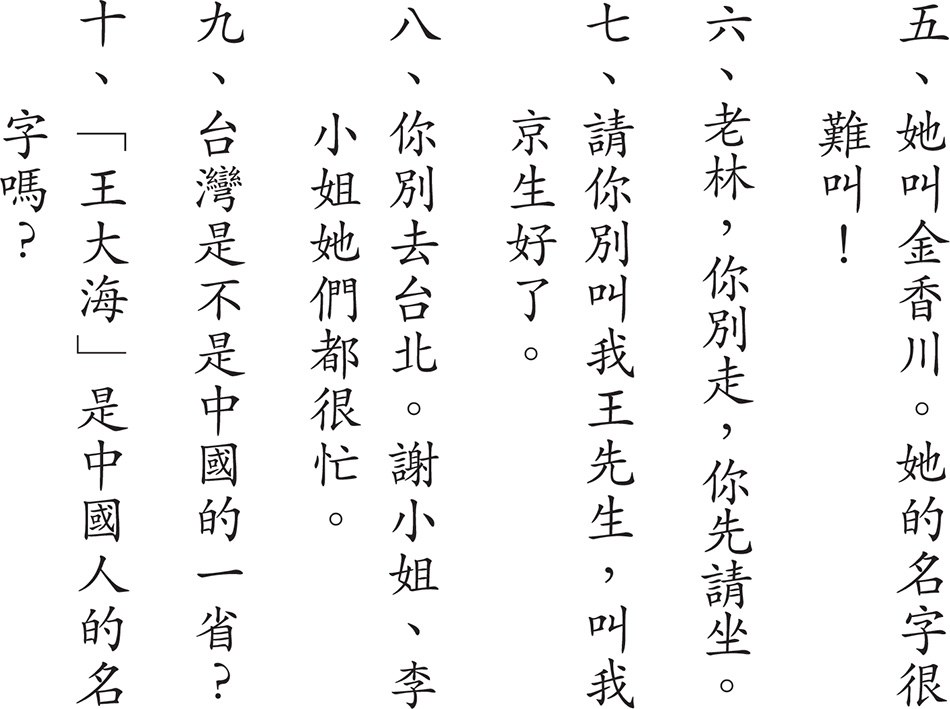

B. CONVERSATIONS

Read out loud the following conversations, including the name or role of the person speaking. If possible, find a partner or partners and each of you play a role. Then switch roles, so you get practice reading all of the lines.

一、

小高:你好!我叫高大明。

小文:你好!我叫文中。

小高:你是我的同屋吗?

小文:是,我们是同屋。

二、

金先生:王先生,你好!

王先生:别叫我王先生,叫我小王好了。

金先生:好,小王。你的名字是不是叫王明?

王先生:不是,我的名字叫王太中。

三、

李大山:你好!我叫李大山。你的名字是⋯⋯?

林京生:我叫林京生,你叫我小林好了。

李大山:小林,你是哪国人?

林京生:我是中国人,你呢?

李大山:我是美国人。

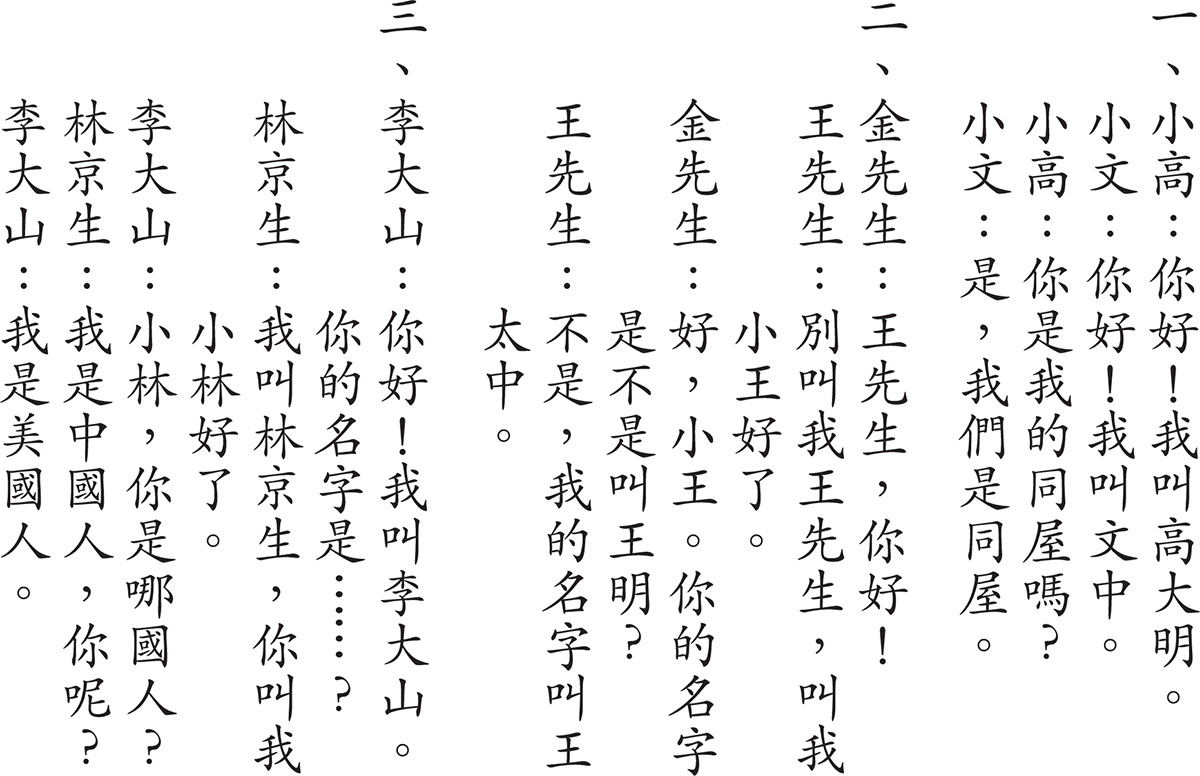

C. CHARACTER DIFFERENTIATION DRILLS

Distinguish carefully the following similar-looking characters, pronouncing each one out loud and thinking of its meaning.

一、同 同 同 问 问 问

二、同 同 同 国 国 国

三、同 问 国 同 国 同 问

D. NARRATIVES

Read the following narratives, paying special attention to punctuation and overall structure. The first time you read a narrative, read it out loud; the second time, read silently and try to gradually increase your reading speed. Always think of the meaning of what you’re reading.

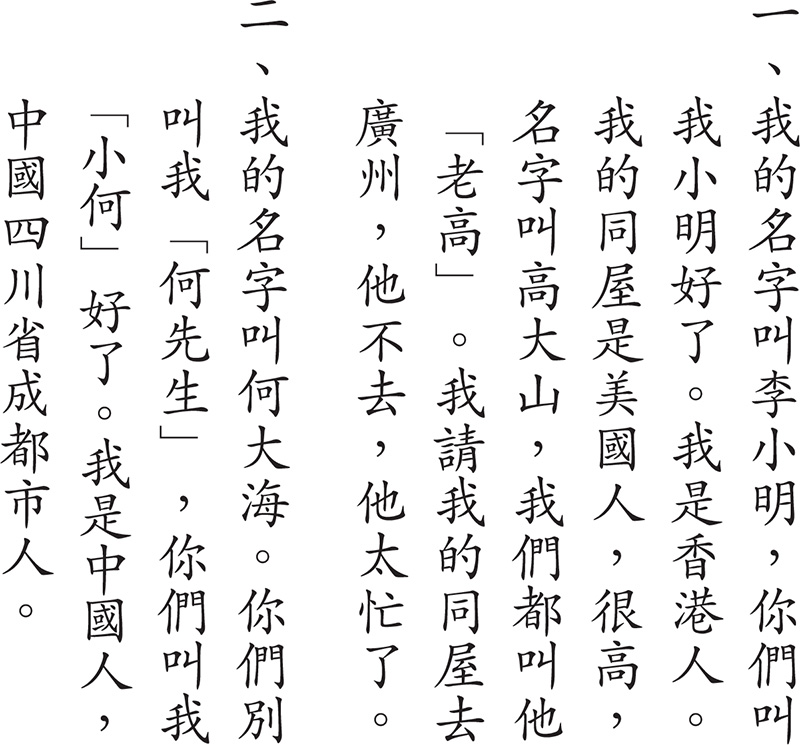

一、 |

我的名字叫李小明,你们叫我小明好了。我是香港人。我的同屋是美国人,很高,名字叫高大山,我们都叫他“老高”。我请我的同屋去广州,他不去,他太忙了。 |

二、 |

我的名字叫何大海。你们别叫我“何先生”,你们叫我“小何”好了。我是中国人,中国四川省成都市人。 |

Reading Exercises (Traditional Characters)

A. SENTENCES

Read out loud each of the following sentences, which include all the new characters of this lesson. The first time you read a sentence, focus special attention on the characters and words that are new to you, reminding yourself of their pronunciation and meaning. The second time, aim to comprehend the overall meaning of the sentence.

B. CONVERSATIONS

Read out loud the following conversations, including the name or role of the person speaking. If possible, find a partner or partners and each of you play a role. Then switch roles, so you get practice reading all of the lines.

C. CHARACTER DIFFERENTIATION DRILLS

Distinguish carefully the following similar-looking characters, pronouncing each one out loud and thinking of its meaning.

Street scene in Kowloon, Hong Kong

D. NARRATIVES

Read the following narratives, paying special attention to punctuation and overall structure. The first time you read a narrative, read it out loud; the second time, read silently and try to gradually increase your reading speed. Always think of the meaning of what you’re reading.

Notes

A1. In this sentence, look at the phrase 你同屋的名字 “your roommate’s name.” Normally, to say “your roommate” you would say 你的同屋, so why is this not *你的同屋的名字? The answer is that, in general, Chinese people do not like the “sound” of several 的 in a row, so they usually delete all the 的 except the last one. In other words, we could say the deeper structure of this phrase was originally 你的同屋的名字 but, when it became a surface structure, the first 的 was deleted, so that the phrase became 你同屋的名字.

A3. In 你的同屋是……?, the 省略号 ( 省略號 ) shĕnglüèhào (……) at the end of the sentence indicates an incomplete question. An English translation would be “Your roommate is…?” Incomplete questions like this are often used in Chinese when one doesn’t wish to ask too directly (“Who is your roommate?”) but still wants, in a more “gentle” manner, to put one’s interlocutor into a situation where he or she is almost forced to complete one’s sentence. Compare similar usage in B3.

A5. Note how 叫 is used in this sentence. The literal meaning of 她的名字很难叫 ( 她的名字很難叫) is “Her name is hard to call out.” In more idiomatic English, we would say “Her name is hard to say” or “Her name is hard to pronounce.” This is because to a native speaker of Mandarin, the syllables 金香川 Jīn Xiāngchuān do not sound pleasant when pronounced one right after another (they are all in Tone One and they all end in nasal finals).

A9. Look at this sentence: 台湾是不是中国的一省?( 台灣是不是中國的一省?) Literally, the sentence means “Taiwan is it or is it not China’s a province?” In good English, of course, we would translate this as “Is Taiwan a province of China?”

D1. Pay attention to the construction 不去 in 我请我的同屋去广州,他不去 ( 我請我的同屋去廣州,他不去 ). Here, 不去 means “didn’t want to go” or “couldn’t go.” The whole sentence could be translated as “I asked my roommate to go to Guangzhou, but he didn’t want to go.” (To express past negative “didn’t,” another word, that we will be taking up in BMC—RW 2-4, would be used.)