3

ADELAIDE,

12 OCTOBER 2012

Alison Connor’s mum’s friend was a Ten Pound Pom called Sheila; with that name, she used to say, she’d fitted right in in Australia. She’d sailed to Adelaide from Southampton in 1967 on one of those dirt-cheap assisted passages, following the promise of a new life in Elizabeth and a job at the Holden car plant, and there, she’d met and married Kalvin Schumer, an engineer, a real Australian, born and bred in Adelaide to German parents and as fine and strapping a man as Sheila had ever laid eyes on. At weekends, he’d wooed her on long trips north out of town to the desert, shooting big red roos to feed to his dogs, and snatching up snakes from the red earth, cracking them to death on a rock, like a whip.

All this was in her letters, which for a while after she emigrated came about once a month, a conscientious and lyrical correspondence that really got on Catherine’s wick. She’d known Sheila Baillie when they were girls in the same street, but then the Baillie family moved to Liverpool, and Catherine only saw Sheila once more, at her own wedding to Geoff Connor, but Sheila hung on to the friendship, never quite grasping either the extent of Catherine’s indifference, or her relationship with the bottle, so she didn’t know that her letters from South Australia, chock full of verve and immigrant zeal, only shovelled further misery and bitterness into Catherine’s soul by flaunting a vivid picture of the world, so different to her own drab orbit.

There was nothing drab about Sheila’s letters, oh no. She detailed her adventures in a looping, gregarious hand and peppered the words and phrases with exclamation marks, as if the tropical climate and lethal spiders and vast horizons weren’t exotic and surprising enough; as if she had to flag them up for her audience in case they missed the best bits. Her traveller’s tales were read aloud to little Alison when the pale-blue, tissue-thin airmail letters arrived addressed to Catherine. If Catherine had ever written back to Sheila, doubtless the tales of life down under would’ve continued, but Alison’s mum was a drinker, not a reader or a writer. She’d only paid any attention to the first letter, and it had made her very cross; Alison didn’t know why. After that, she’d pick them up from the mat and flap them disparagingly, like used Kleenex, and say sour things such as, ‘Heat and dust and bloody spiders. Does she think we’re interested?’ Then she’d drop the unopened envelope in the kitchen bin and later, when the coast was clear, Alison’s brother Peter – older than her by six years – would fish it out from among the tea leaves and peelings, slice a knife though the seal with a piratical flourish, and hold ‘story time’ in his bedroom, reading the letter aloud to his sister, both cross-legged on his bed.

Sheila’s letters filled Alison with a kind of courage and resolve. She kept them as totems, slipping each new one between the base of her bed and the mattress, and when the letters stopped coming, when Sheila stopped writing to Catherine, Alison felt bereft. It never occurred to her that she could have written back herself; well, she was so young, she didn’t have the know-how or the confidence or the money for a stamp, and she was growing up with Catherine for a mother. But she treasured the letters, read and reread them until all the best parts were memorised, so that even when Catherine found the stash one day and put them on the fire to punish her for treachery and deceit, Alison still had them in her mind and could recite whole paragraphs, reverentially, as if they were sonnets or psalms.

There are cockatoos in the trees here, white with yellow crests, and noisy devils! They eat the plums from our garden and stare at us with bold, black eyes. Koalas, sweet as pie, curl up in the boughs of giant gums, endlessly sleeping, like old men after Sunday dinner. The spiders are as big as a man’s hand, spread out flat. Imagine that! But they’re not the ones to worry about – the killers are the redbacks, much, much smaller, but lethal when rattled. Kalvin says always look in the mailbox before putting your hand in!

As for the heat! The grass in our back yard steams in the mornings as the sun comes up and sometimes the road starts to melt! We grow flowers, though. Poinciana do well, but so do petunias and humble pansies, if they get plenty to drink. But the dust puffs up round my feet when I’m gardening and even though the desert’s a long drive away, somehow it looms, hot and red, and I never forget it’s there.

This is a wonderful country, Catherine, a lucky country, and you’ll know what I mean when you come to visit. Do come!

Those words lived with Alison, once she’d heard Peter read them. And you’ll know what I mean when you come to visit. Did this person, Sheila, expect them? Might Alison and Peter be given the chance to grow up in a faraway place called Elizabeth, instead of Attercliffe? Peter didn’t know, and their mother couldn’t be asked: not this, nor anything else. Catherine Connor had no patience for questions. They reminded her of her responsibilities.

So these memories, all of them, the pleasure and the pain, bloomed in Ali Connor’s mind every time a journalist, interviewing her about her new success, asked what had brought her to Adelaide. The climate, she’d say. The Adelaide Hills, the gracious city, the infinite ocean, the food, the rainbow-coloured parrots, the luminous sun-flooded early mornings, the inky nights, the space to write. And all these things were reasons she’d stayed, but none of them were why she’d come. She’d always kept those to herself, hadn’t told her husband, hadn’t even told Cass Delaney, who thought she knew every secret skeleton in Ali’s closet. They were sitting together in a café in North Adelaide, reunited after Cass’s working week in Sydney, and she’d heard Ali three times today already, twice on the telly on News Breakfast and Sunrise, and once on the radio, and soon Ali’d be back at the ABC studios for a pre-record with the BBC. Cass was buzzing from it all, getting a huge vicarious kick from her friend’s moment under the media gaze – but why, she wanted to know, did Ali always sound so bloody cagey?

‘All those platitudes!’ Cass said now. ‘Just quit the crap about the scenery, it makes you sound pretentious.’

‘Don’t listen then,’ Ali said. ‘I’d prefer it if you didn’t anyway, to be honest. It makes me anxious.’

‘You sound all uptight, like you don’t wanna be there. You’re an Aussie, girl! Behave like one, hang loose, spill the beans. Tell ’em about how you picked up Michael in Spain, and he followed you for weeks, like a sad puppy, before you caved in and crossed the globe with him.’

Ali laughed, then sipped her coffee. ‘Honestly, Cass, I’m just being myself, and if it was up to me, I’d say no to all this publicity. I’m only doing it for that nice girl Jade at the publishers. She’s making all this effort, I feel I have to turn up.’

‘Oh, c’mon, you gotta bask in the spotlight while it’s still on you.’

‘I wish you could do it for me instead. You’d be so much better at it.’

‘I’ve never been known to shrink from attention, this is true.’

‘I just like sitting alone at a desk, making up stories and not having to get dressed or wash my hair if I don’t feel like it.’

‘You gotta wise up,’ Cass said. ‘You’re famous now, whether you like it or not, and if you don’t start coming over as a warm human being with a story to tell, people might take against you. You don’t want the tide to turn.’

‘Rubbish. I’m not famous at all,’ Ali said. She looked about her, at all the oblivious people around them, eating and talking and ordering food. ‘See? Nobody cares. My book’s quite well known, but I bet half the people who’ve read it couldn’t name the author, and thank God for that.’ She leaned forwards, elbows on the table, resting her chin in two cupped hands. ‘So, how was your week?’ she asked.

‘Yeah, so-so,’ Cass said. ‘Mad busy, as usual. Wrote a big piece for the magazine, “Greed as the new economic orthodoxy”, if you’re interested.’

Ali shook her head. ‘Nah, not really.’

Cass laughed, and winked at her. ‘Hey, are you coming to Sydney any time soon? I’ve got a new squeeze, Chinese-Australian guy, a bit short for me, but they’re all tall enough when they’re lying down.’

‘Oooh, what’s his name?’

Cass pretended to think for a while. ‘No,’ she said. ‘It escapes me.’

Ali laughed and said, ‘Good-looking, though?’

‘Well, he wouldn’t set Sydney Harbour on fire, but he’s quite cute. Come and see for yourself, but come soon before he gets the flick.’

‘Well, I might just do that. My editor’s on at me for a date, she wants me to meet her boss and talk next book.’

‘And is there a next book yet?’

‘Nope.’

‘Still no ideas?’

‘Plenty, but none that relate to Tell the Story, Sing the Song.’

‘Ah, gotcha, they want more of the same?’

‘Precisely. I haven’t yet decided whether I’m willing to bend enough to keep them happy.’

‘You’ve written the new Thorn Birds, babe, you can do what you like. You not eating your cake?’

She shook her head. ‘I told you I didn’t want one. Coffee’s all I wanted.’

‘C’mon! We don’t want to hear your belly rumbling on the radio.’

Ali shook her head, then checked the time on her phone. ‘Look, I’m going to dash home before that interview,’ she said.

‘What? Why?’ Cass was supposed to be driving her up there. That was the plan.

‘I just want to, not sure why.’ Ali stood up and drained her coffee. ‘I have time: I’m not due at Collinswood for another forty-five minutes. I’ll drive myself there from home, don’t worry.’

‘You’ll be late.’

‘I won’t!’

‘Seriously, Ali, don’t be late for the BBC. They’re your people, after all.’

Ali laughed. ‘Cass, you talk such bullshit. Not five minutes ago you told me I was an Aussie.’ She slung a small black leather rucksack over her shoulder and pushed her hair away from her eyes, tucking a few strands behind her ears. Her lovely face was pale, Cass thought, eyes a little strained, and perhaps she was a little too thin.

‘Thank God it’s radio,’ Ali said, as if she could read her mind. ‘At least it doesn’t matter what I look like.’

‘Well, you look ravishing as usual,’ Cass said. ‘But a bit of lippy wouldn’t hurt, in case there are autograph hunters?’

‘Very funny,’ Ali said, and she blew a kiss and swung away.

Cass watched her go. In a desert island situation, if it came down to a choice between Ali Connor or a young Paul Newman, she’d have to regretfully push Paul back into the sea, because she couldn’t do without Ali, no way. Cass had heaps of friends in Sydney, women and men, and she loved the buzz of the city’s nightlife, but very often by Thursday or Friday she would fly home to her Adelaide roots, and Ali was top of the list of reasons why. She saw her friend thread her way through the busy café, open the door on to the street, step outside into the sunshine where she paused to put on her sunnies, then she was off.

‘I’m right behind you, sweetheart,’ Cass said, watching her go.

It was only just over a kilometre from Jeffcott Street to her house, but still, Ali walked briskly, knowing she was probably pushing her luck to get home and then across to Collinswood in time for the interview. She could have – should have – stayed put with Cass, had a second coffee, then be driven in her smooth, silent, air-conditioned company Merc up to the ABC studios, to arrive serenely on time. But she’d faced three presenters today already, and a whole battery of personal questions, and she had an overpowering desire to shut the door on the world for a while, shut it even on Cass. She half walked, half ran, head down, full of purpose, through the streets of North Adelaide, and by the time she reached the house, her face and throat, and her bare arms, were covered in a fine layer of sweat, and she experienced a swell of pure relief as she put her key in the front door and opened it. Once inside, she closed it again and stood for a few moments on the burnished parquet floor of the hallway, breathing in and out, in and out, letting the house calm her, absorb and dissipate her tensions, hold her steady between its solid colonial walls.

This house was very fine: a stately bluestone mansion, Michael’s inheritance. They were already husband and wife when he first brought her here to meet his family, but even so she had been promptly – and somewhat coldly – billeted by his mother in one of the spare bedrooms, and only after a full twelve months of married life did she permit them to openly share a room, and a double bed. Margaret McCormack had been a force of nature, an impossible, indomitable, high-handed martinet of a woman who believed her son had been hoodwinked by Ali, because after all, what did the girl have to offer? Margaret saw no cachet in the English accent, was unmoved by Ali’s obvious beauty, and was maddened almost beyond endurance that the young woman quickly found herself a job behind a bar in a pub on Hutt Street. But the young couple toughed it out, and Michael told Ali that his mother would love her in the end, if they just played by her rules when they were in the house. Anyway, he said, this house was a treasure: why pay rent somewhere inferior, when they had no money as it was? So, for a year, Michael – an adult, a medic, a married man – crept across the expansive Turkish rug on the first-floor landing to find Ali, awake in her chastely single bed, waiting for him. Hard to imagine, if you’d never met Margaret, that such a situation could go unchallenged, but they perfected the art of silent sex, and Margaret – who must have known what was going on, because only a fool could not have known, and she was no fool – seemed satisfied that her supremacy remained undiminished. A year after she arrived, to the very day, Ali had gone upstairs to find the single bed stripped of linen, and her belongings – clothes, toiletries, cosmetics – gone. Margaret, behind her on the landing, had said, ‘Your things are in Michael’s room. I had Beatriz move them while you were out. No need to thank her, she’s more than adequately paid. You may, however, thank me.’

Now, of course, Margaret was long gone, but Beatriz was still here and she was sitting at the counter shelling peas when Ali walked into the kitchen. The old lady had her long grey hair piled into its habitual turban, and she wore a quaint, outdated housecoat, bright florals, gold buttons, to keep her clothes clean. Her fingers worked expertly at the pods and her broad, open face creased into an affectionate smile when she saw Ali.

‘Ali, my girl,’ she said. She held out an unpodded shell, and Ali took it, cracked it open, and tipped the row of peas into her mouth. Beatriz looked at her with love.

‘I’m not here for long,’ Ali said through the peas. ‘I have to go up to Collinswood, to the studios.’

Beatriz shook her head sadly. She had such expressive eyes, thought Ali; they could communicate every emotion: joy, desire, sorrow, disdain, anger, amusement. Right now, they showed only pity.

‘Busy, busy, busy,’ she said. ‘Always busy, always running somewhere, never time to sit with me and shell the peas.’ Her Portuguese accent was undiminished even after nearly sixty years in Adelaide, but it was always only a question of tuning in, like learning to love a different kind of music.

She bent her head, getting back to the task in hand, and Ali watched her for a few moments, then said, ‘How’s your hip today, Beatriz?’

Beatriz looked up again and said, ‘No better, no worse.’

‘Don’t sit for too long,’ Ali said. ‘Have a walk, keep it moving. Have a dip, be a devil.’

Beatriz threw back her head and laughed, and said, ‘You know how I hate getting myself wet.’

‘It’s very therapeutic,’ Ali said. ‘And there’s a pool out there that nobody seems to use any more.’ She took a glass tumbler from the cupboard and poured water into it from the bottle they kept in the fridge. It was shockingly cold, and Ali felt a stab of pain at her temples, and in her teeth. Beatriz was involved with the peas again, and Ali wandered out of the open back door into the garden, where the irrigation system had turned on and was sprinkling the lawn. A small flock of rainbow lorikeets were dancing in the fine arc of drops, and when Ali kicked off her sandals and joined them on the damp grass, they eyed her beadily, and stood their ground. She walked across the lawn to the swimming pool – a narrowish rectangle of aquamarine, startling against the old stone pathway that surrounded it – hitched up her skirt, and sat down on the very edge, so that her feet and calves were submerged, almost up to the knees. Then she lay down, and let the warmth of the stone and the damp cool of the grass support her, while the water lapped, barely perceptibly, around her legs. She closed her eyes against the too-blue sky, and listened to the squawking chatter of the birds and the thrum of water from the sprinkler, and allowed her thoughts to float loose and free; then a shadow fell across her face and she heard Stella’s voice.

‘Mum, your skirt’s soaked.’

Ali opened her eyes. Stella, impassively beautiful, stared down at her. She was seventeen, and she had Ali’s dark brown hair, Ali’s hazel eyes, Ali’s nose and mouth and chin: but her attitude was all her own.

‘What the hell are you doing anyway? You look so weird.’

Ali closed her eyes again. ‘Cooling down, chilling out,’ she said, and then, after a pause, ‘Don’t pass remarks, Stella.’

The girl dropped down next to her and crossed her legs, and Ali opened one eye to take a sideways look at her younger daughter. She was chewing the nail of her left thumb and staring at the pool water.

‘You good?’ Ali said.

Stella shrugged.

‘What?’ Ali pushed herself back up into a sitting position and noticed as she did so that Stella was right, her skirt was soaked. ‘Stell, what’s up?’

From the house, Beatriz called, ‘Ali, Cass’s here with her car, says she’s driving you to Collinswood,’ and Stella looked at Ali, and tutted and rolled her eyes.

‘Cass can wait,’ Ali said to Stella. ‘She wasn’t supposed to come here anyway.’

‘Whatever,’ Stella said. She turned away with a sort of gloomy fatalism. ‘Just go.’

‘Stella,’ Ali said. ‘What’s wrong, darling?’

Then Cass’s voice came, loud and clear, through the open back doors. ‘Ali Connor, your time is now,’ she shouted, completely misjudging the mood out there in the blissful perfection of the McCormack garden.

‘Zip it, Cass,’ Ali shouted.

‘Don’t try to be cool, Mum,’ Stella said with that flat, teenaged disdain.

‘I’m not trying to be cool. I’m just pissed off with Cass. What’s going on, Stella?’

‘Coo-ee, Stella babe,’ Cass called, waving wildly from across the garden, but Stella barely glanced at her.

‘Seriously, Mum, just go.’

‘Look, OK, I better had, but I’ll catch you, right? Later, or in the morning? I have to get to the studios again, it’s—’

‘—your book, I know, I know, off you go.’ Stella spoke with that toneless, disillusioned voice she used to communicate infinite ennui, and Ali knew there was no talking to her anyway now this mood had descended, so she left her by the pool, staring malevolently at the ripples in the water.

‘Uh-oh, trouble?’ Cass said as they left the house.

‘It’ll pass,’ said Ali.

The book. The book. A great big readable tome, 150,000 words, straight into paperback, and as far as Ali was concerned no better and no worse than her previous three novels, which had been modestly well received in Australia but were unheard of anywhere else. But Tell the Story, Sing the Song was officially a phenomenon. A quiet start after publication, then a speedy, influential burst of online reviews, a flood of sales, book club fever, and a scramble by the publisher to get the next print run out, then a phone call to her agent in early October from Baz Luhrmann’s office: name the price for the rights, they said; Baz wants this, Nicole’s on board, so’s Hugh. Thousands of books were selling each week around the world, and Ali’s paltry advance had earned out in record time. For the first time in her life she was making money from her writing, and Jenni Murray, in an interview for Woman’s Hour on BBC Radio 4, was asking her how this felt.

‘Unreal,’ Ali said, headphones on, alone at the green baize desk in an ABC recording suite. Through the glass wall she was looking directly at Cass who’d come into the studios with her and was sitting at the panel, reapplying her make-up and listening in. A young studio manager chewed gum and looked thoroughly disengaged, but she kept a weather eye on the levels, and the mics.

‘Unreal, and slightly obscene,’ Ali added.

‘Obscene?’ Jenni Murray said. ‘That’s an unusual choice of word.’

‘Well, I find myself in an unusual situation,’ Ali said. She could feel it happening again; feel the drawbridge coming up. And the sound of her own voice in this situation stunned her. Her accent was considered very English, comically so, among her family and friends in Adelaide, but now she heard the broadcaster’s rich, modulated, faintly plummy tones and her own voice bore no comparison. It lacked substance, she thought: a thin, hybrid drawl. On her side of the window, Cass made sweeping gestures with her hands, urging her to expand. Ali nodded. Yeah, yeah, hang loose.

‘Does the money make you feel uncomfortable?’

‘It makes me think,’ Ali said, ‘about the arbitrary nature of success.’

‘So you didn’t know, when you had the idea for Tell the Story, that it might strike gold?’

‘Well, no, of course I didn’t,’ Ali said. ‘My three other books had done nothing of the sort, and to be honest I think they have no less merit than this new one. Sometimes a book just captures the public imagination, I suppose.’

‘So why do you think it succeeded in the way it has?’

‘Not sure,’ Ali said. ‘If I knew that I guess I would’ve written it sooner.’ This was meant to be funny, but as soon as the words came out she knew it only sounded rude. ‘No, seriously,’ she went on, trying to redeem herself, ‘I suppose it tells some truths about Australian life, about our collective past. And it’s accessible, but also thought-provoking; at least that’s what I was aiming for. It reflects a lot of the preoccupations of right-thinking Australians.’

‘The plight of the indigenous people, you mean?’

‘Among other things, yes, and I’ve plenty to say about that, but it’s poverty that my story addresses, and although that’s predominantly and historically a black issue, it can cripple white people too, especially in rural parts of South Australia, and I don’t know how much you know about the state, but the rural parts are vast-beyond-vast. We have a cattle station here that’s bigger than Wales, if that helps paint the picture.’

‘It does indeed, the mind boggles. And how much research did you have to do? It’s such a multi-layered book, perhaps that’s why it appeals to such a diverse readership.’

‘Thanks, yes, I hope it does. I did heaps of research for some aspects of it, not much at all for others. The music, for example, the young Aboriginal singer, I had her in my head and ready to go.’

‘She’s a wonderful character. Is she real?’

‘Yes, and no,’ Ali said. ‘Like most aspects of the book.’

‘Well, I couldn’t put it down,’ Jenni Murray said. ‘You’ve written a fascinating novel, and as I travelled into London by train this week, I saw so many people reading it.’

‘I guess the rest of the world must be more interested in Oz than we realised,’ Ali said. ‘Also, it’s set in Adelaide, and people don’t hear so much about this city. I think that maybe makes the book different, and appealing.’

‘Because Adelaide is different and appealing?’

‘Yes, I think so. We get a lot of stick from Sydney and Melbourne for being boring, but I reckon that’s sour grapes. To me, it’s always seemed a kind of paradise,’ Ali said.

‘Gosh, praise indeed!’ But because this wasn’t a question, Ali said nothing, so Jenni Murray filled the silence. ‘You’ve lived in Adelaide for thirty years or so, but of course, you’re a Sheffield lass by birth?’

‘Yes,’ Ali said. ‘Correct.’

‘And how have the people back home reacted to your success?’

‘Home?’ Ali said.

‘I beg your pardon – I mean, in Sheffield, in Attercliffe?’

‘Oh,’ Ali said flatly. She hesitated, then said, ‘I don’t know. I mean, I’m not in touch with anyone there, not any more.’

‘Family?’

‘Nope.’

‘So Adelaide really is home, in every sense?’

‘Yep, one hundred per cent.’

Afterwards, in Cass’s car, she dug out her phone and switched it on to scroll through the myriad messages and notifications waiting for her on the screen. She’d refused her publicist’s suggestion that she join Facebook, but had begrudgingly agreed to be a presence on Twitter, and it still amazed her how something so essentially trivial and self-referential could be held in such fawning esteem by so many. However, each day she garnered new followers, and whenever she posted something it was immediately ‘liked’ and retweeted again and again, and if she didn’t have a solid core of humility and good sense running through her, she might have begun to believe she was loved and adored by thousands. It was all cobblers, she thought, but needs must.

‘I’m going to please Jade and tweet about the wonders of Woman’s Hour,’ she said to Cass.

‘Good girl, that’s the spirit. You did well back there, darling, you sounded très switched on.’ She reached out and turned on the radio, and the car was suddenly filled with Motormouth Maybelle singing ‘Big, Blonde And Beautiful’. Cass whooped and joined in; Ali groaned.

‘Really?’ she said. ‘Hairspray?’

‘All hail, Queen Latifah,’ Cass said, turning it up.

Ali laughed and said, ‘You really should do musical theatre,’ then she looked back at her phone, running her eyes down the list of notifications.

‘Oh,’ she said suddenly, and her voice was strange.

‘What?’ said Cass, immediately alert. ‘Trolls?’

‘No, no,’ Ali said. ‘No. No.’

‘That’s a lot of “no”s.’

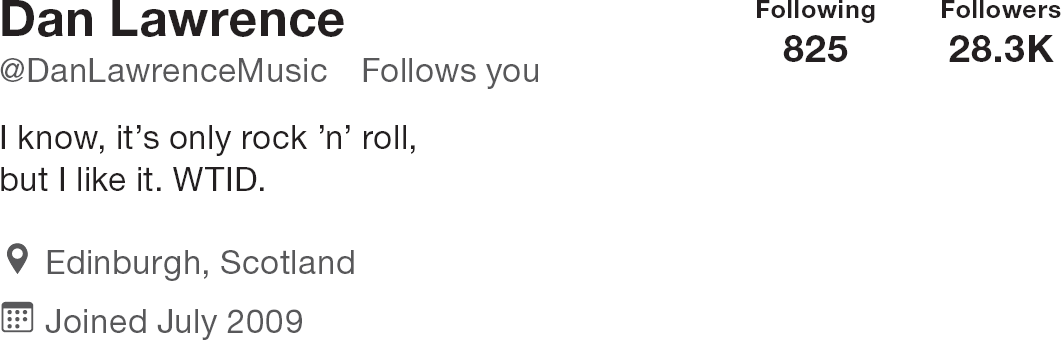

Ali was silent. Dan Lawrence followed you.

‘Ali?’

She was looking at Dan’s face now – a straightforward photo, no gimmicks, just him in a white T-shirt, looking directly at her – and after all this time, after all these years, he was utterly familiar. Daniel Lawrence. Oh, heavens, she thought. She forced herself to take a long, deep breath, but it shook on the exhale and gave her away.

‘Ali? What’s wrong?’

She stirred herself and managed a smile. ‘Oh, nothing, nothing, a name from way back, that’s all. Took me by surprise.’

She tapped on Dan’s name to open his profile, and then stared at the screen of her phone.

‘I’m at a severe disadvantage here, babe,’ Cass said. ‘I can’t see what’s grabbed you.’

Dan Lawrence.

Daniel Lawrence.

Daniel. That lovely boy, a man now, and there he was, smiling at her again.

‘Ali?’ Cass said, worried now, because her friend was staring at her phone in a most uncharacteristic manner, and she didn’t answer, but was gone, temporarily: lost, somehow.

‘C’mon, talk to me,’ Cass said, and switched off Maybelle. ‘What you looking at?’

Ali still didn’t speak, but because they’d stopped at a red light, she tilted the screen so that Cass could see.

‘Mmm, nice,’ she said. ‘Right up my alley. Great stubble. Who is he?’

‘He was Daniel,’ Ali said.

‘Dan now, evidently. What’s that?’ She pointed. ‘WTID? Is that some kind of code? Does it mean anything?’

‘Yes,’ Ali said. ‘It means Wednesday Till I Die.’

‘Wednesday? Why Wednesday, why not any other day of the week?’

‘Football team,’ Ali said. ‘Soccer.’

‘English guy?’

‘Yeah.’

‘Right on,’ Cass said, leaning over for a better look. ‘Oh yes, keep on stirring, baby, till it hits the spot.’