Free water is the shining splendor of the natural landscape. From the bubbling spring and upland pool to the splashing stream, rushing rapids, waterfall, freshwater lake, and brackish estuary and finally to the saltwater sea, water has held for all creatures an irresistible appeal. To some degree, we humans still seem to share with our earliest predecessors the urgent and instinctive sense that drew them to the water’s edge.

Perhaps at first they were drawn only for drink, to lave hot and dust-streaked bodies, or to gather the bounty of mollusk and fish. Later, water for the cooking pots would be dipped and carried in gourds, skins, hollow sections of bamboo, and jars of shaped, fire-baked clay. Perhaps our affinity for water has increased with the discovery of its value in gardens and irrigation and with the knowledge that only with moisture present can plants flourish and animals thrive. It may be because in the deep, moist soils of the bottomlands the grasses are richer, the foliage more lush, and the berries larger and sweeter. Here, too, the refreshing breeze seems cooler and even the song of the birds more melodious.

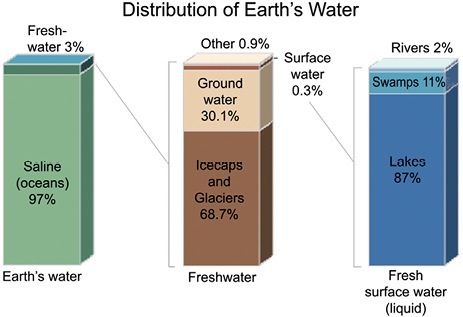

Almost every human activity is dependent upon the use of fresh water, but of all the water found on planet Earth only 3 percent is fresh and, of that, most is frozen in glaciers and polar regions, making less than 1 percent of the Earth’s fresh water potentially available for human use.

In planning the use of land areas in relation to waterways and water bodies, a reasonable goal would be to take full advantage of the benefits of proximity. These benefits would seem to fall within the following categories.

Water Supply, Irrigation, and Drainage

When these are important considerations, the area of more intensive use will be located near the sources. Those site functions requiring the most moisture in the soil or air will be given location priority. Usually gravity flow will have much to do with the plan layout.

USGS

Irrigated fields will be established below points of inlet where possible and be so arranged that lines or planes of flow will slope gently across the contours to achieve maximum percolation and continuity.

Drainage will be maintained whenever possible along existing lines of flow, with the natural vegetation left undisturbed. It would be hard to devise a more efficient and economical system of storm drainage than that which nature provides. Runoff from fertilized fields or turf will be directed to on-site retention swales or ponds so that the water may be filtered and purified before reentering the source or percolating into the soil to recharge the water table.

More than two-thirds of the earth’s surface is submerged in saltwater. The balance of surface area is generally underlaid with fresh water that fluctuates slowly in elevation and flows imperceptibly through the porous aquifers toward the waiting sea.

Use in Processing

When drawn from surface streams or water bodies for use in cooling, washing, or other processes, water of equal quantity and quality is to be returned to the source. Makeup water may be supplied from wells or public water supply systems.

In Florida at least 65 percent of all marine organisms, including shrimp, lobsters, oysters, and commercial and game fish, spend part of their life cycle in the brackish waters of tidal estuaries and coastal wetlands.

Within the past century, over half of the state’s wetlands have been dredged, filled, or drained.

The only way to protect fish and wildlife is to protect their habitat.

Transportation

When waterways, lakes, or abutting ocean are to be used for the transport of people or goods, the docking installations and vessels are to be so designed and operated that the functional and visual quality of the water is at all times ensured.

Microclimate Moderation

The extremes of temperature are tempered by the presence of moisture and by the resulting vegetation. This advantage may be augmented by the favorable placement of plan areas and structures in relation to open water, irrigated surfaces, or water-cooled breeze.

Wildlife Habitat

Lakeshores, stream edges, and wetlands together form a natural food source and habitat for birds and animals. When flora and fauna are to be protected, the indigenous vegetation is to be allowed to remain standing whenever feasible, and continuous swaths of cover are to be left intact to permit wildlife to move from place to place unmolested. The denser growth is usually concentrated along water edges and converging swales.

Recreational Use

Our streams and water bodies have long provided our most popular types of outdoor recreation such as boating, fishing, and swimming. Along their banks and shores is found the accretion of cottages, mobile home parks, and campsites that attest to our love of water. It is proposed that in long-range planning, with few exceptions, all water areas and edges to the limits of a 50-year flood would be acquired and made part of the public domain.

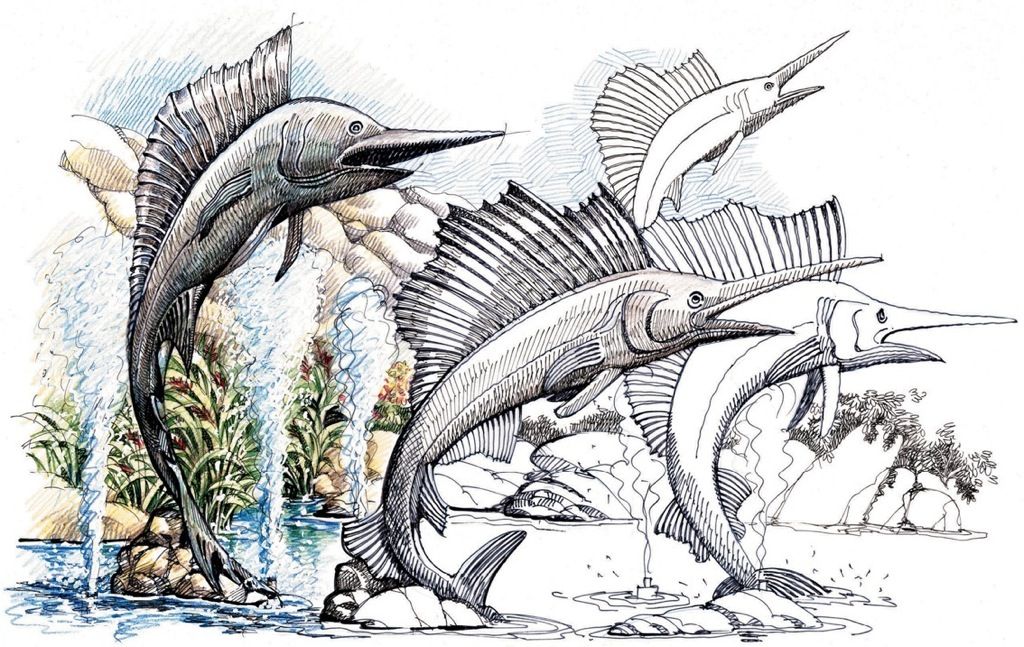

Scenic value. Burton Landscape Architecture Studio

Recreation value. Barry W. Starke, EDA

If there is magic on the planet, it is contained in water … its substance reaches everywhere; it touches the past and prepares the future; it moves under the poles and wanders thinly in the heights or air. It can assume forms of exquisite perfection in a snowflake, or strip the living to a single shining bone cast up by the sea.

Loren Eiseley

Scenic Values

For most people, the glimmer of sunlight on open water is sure to elicit an exclamation of discovery and delight. The feelings may be expressed as a shout of triumph or as a silent upsurge of the spirits. Not only the sight but as well the sounds of water evoke a sense of pleasure. It would seem that we are so acutely attuned to the language of water—the trickle and gurgle of ice melt, the splash of the stream, the lapping of water on lakeshore, the surf crash, even the cry of shorebirds—that we can almost see with our ears.

A glimpse, a view, an unfolding panorama of the aquatic landscape is a scenic superlative. Streams and water bodies are the punctuation marks in reading the landscape. They translate for us the landforms and the story of their geologic formation. They set the mood; they articulate; they intensify. They give the essential meaning. What is a prairie without its sloughs? A meadow without its meandering brook? A mountainside without its cascade? A valley without its river?

The subsurface reservoir of fresh water may be tapped and used freely as long as the local supply is not thereby depleted. Depletion is caused not only by overuse but also, and more often, by destruction of the natural ground covers and vegetation, which would otherwise retain precipitation for filtration to the aquifer.

Site Amenity

Fortunate is the landowner whose property includes or borders upon an attractive stretch of water or affords even a distant view. In landscape and architectural planning, a chief endeavor will be the devising of relationships that exact the full visual and use possibilities.

Submarine ecosystems. © William Rafti of the William Rafti Institute

Aquatic environment. Kongjian Yu/Turenscape

Most attributes of nature—the hills, the trees, the starlit sky—are usually taken for granted, but the value of free water is not. Where it exists, as in the form of pond, stream, lake, or ocean, the adjacent landholdings are eagerly sought. They are prized as sites for parks and parkways, for homes, institutions, resort hotels, and other commercial ventures. It could almost be stated as a law of land economics that “the closer a site to open water, the higher its value as real estate.”

From upland spring to ocean outfall the river basin, river, and all its tributaries are part of a unified system.

In the past, freshwater in all its forms has been used, and too often misused or wasted, as if these were God-given privileges. Except in irrigated lands, where water rights and supply are jealously guarded, there has been little concern for what is happening upstream or downstream unless the flow should be cut off or increased to the point of flooding.

Water flows, inevitably, from source to receiving ocean basin. This continuity of rivulets, streams, and rivers can be readily observed. Not so obvious are the sequential and interacting relationships of the ponds, lakes, and wetlands. These, too, are links in the chain of flow. They are affected not only by the things that happen at their sides but by all that transpires within the upper watersheds or the subsurface aquifers that feed and help sustain them. These same subsurface water-bearing, water-transporting, water-yielding strata provide, also, the groundwater essential to farmland, meadow, and forest and to maintaining the level of the well fields from which our water supplies are drawn.

Water and water areas well used can benefit all who live within their sphere of influence. If, however, they are unwisely used, contaminated, or wasted, dependent life is thereby threatened, sometimes with minor loss or inconvenience, sometimes with major disaster, as by devastating drought or overwhelming flood.

Fresh water is a renewable resource, yet the world’s supply of clean, fresh water is steadily decreasing. Water demand already exceeds supply in many parts of the world and as the world population continues to rise, so too does the water demand. Awareness of the global importance of preserving water for ecosystem services has only recently emerged as, during the 20th century, more than half the world’s wetlands have been lost along with the valuable environmental services for Water Education. The framework for allocating water resources to water users (where such a framework exists) is known as water rights.

Tidal wetlands. Barry W. Starke, EDA

It is only recently that entire river basins have come to be studied as unified and interrelated systems. Such a rational approach increases rather than limits the possibilities of fuller use and enjoyment and sets a workable framework within which all subareas may then be better planned.

Any consideration of the flow of surface or subsurface water leads one to the obvious conclusion that only comprehensive watershed management makes any sense at all. A parcel-by-parcel approach to the use of river-basin lands can only fracture the contiguous water-related matrix and disrupt the natural systems.

Problems

The problems to be precluded are those of overuse, rapid runoff, erosion, siltation, flooding, induced drought, and contamination. Simply stated, any use that causes one or more of these abuses to any significant degree is improper and should not be condoned. It can be left to biologists and legal experts to define a significant impact. But it can no longer be left to individuals or groups to determine whether or not their activities may cause harm to their neighbors, no matter if the “neighbors” live next door or at the river mouth 1,000 miles downstream.

What happens in the wheat fields of North Dakota can have a telling effect on the working of the lower Missouri and Mississippi rivers. What happens or doesn’t happen on the forest slopes of the upper James River may decimate the wildfowl yield of the distant salt marsh or contaminate the oyster beds of Chesapeake Bay. In Florida a cloud of spawning shrimp may die where the Apalachicola River debouches, because of an oil spill on a tributary two states away.

Every activity which impacts a resource, such as the Chesapeake Bay, imposes a cost and that cost must be paid by someone. For years, we cheerfully operated under the assumption that where the environment and natural resources were concerned we could operate outside the laws of nature and economics. Cities disposed of their sewage for “free” by simply directing their outfalls to the nearest river. Factories poured wastes into the bay and its tributaries at little or no cost—to their owners. Unfortunately, even though the cost of such activities did not show up on any ledger book, they were being paid for, with heavy interest, by—the downstream municipality forced to find another water supply, the waterman facing condemned oyster grounds, the seafood packer forced to look further and further afield for products to market—all of them picked up the tab for this “free” activity.

W. Tayloe Murphy

In most nonarid parts of our land it is assumed that the supply of freshwater is limitless. It is not. It has recently been common for reservoirs and wells to reach such low levels that whole regions are alerted and rationed. Along much of our coastline, the aquifers that flow underground to the oceans have been so lowered by drawdown that saltwater intrusion for many miles inland has been a vexing problem.

The normal solution to such shortages has been to extend aqueducts, no matter how far, to tap additional sources. Serious thought has even been given to the massive melting of the arctic icecap as a source of supply. This, even as we are beginning to realize the disastrous effects of global warming. Today the supply of freshwater is not equal to our use (or misuse) and demands. This has become a major land planning consideration.

Widespread irrigation and its exhaustion of the freshwater reserves is believed to have caused the demise of the ancient Mayan culture. In the United States in contemporary times it is not far from posing an impending threat to our style of life as we have known it.

The irrigation of thousands upon thousands of acres of otherwise parched semidesert, converting it into lucrative farmland, was a good thing as long as the water was abundant. Overuse, however, has dried the beds of such rivers as the Colorado and lowered the levels of water tables nationwide. Recently, newly assembled macrofarms with rolling irrigation machines gush fountains of potable water skyward, while in nearby homes, faucet flows have been reduced to a trickle.

Beyond and exceeding the drain of agricultural irrigation, the sprinkling of untold thousands of lawn areas has caused a major depletion of our nation’s water supply. It is said that the vast nationwide acreage of lawn under irrigation exceeds that of all cropland in New England. These are but examples of our prodigious waste. We think nothing of using 30 gallons in the taking of a shower, while in many countries the daily water consumption of an entire family is carried home from the stream or well each morning in a jar on the daughter’s head. It is time for planners to adopt a new approach to water conservation, use, abuse, reuse, and replenishment.

Ten Axioms of Water Resource Management

Within each rationally defined hydrographic region:

- Protect the watersheds, wetlands, and the banks and shores of all streams and water bodies.

- Minimize pollution in any and all forms and initiate a program of decontamination.

- Gear land use allocation and development capacities to the available water supply, rather than vice versa.

- Return to the underlying aquifer water of quantity and quality equal to that withdrawn.

- Limit use to such quantities as will sustain the local fresh-water reserves.

- Conduct surface runoff by natural drainageways insofar as feasible rather than by constructed storm sewer systems.

- Utilize ecologically designed wetlands for wastewater treatment, detoxification, and groundwater recharge.

- Promote dual systems of water supply and distribution, with differentiated rates for potable water and that used for irrigation or industrial purposes.

- Reclaim, restore, and regenerate abused land and water areas to their natural healthful condition.

- Work to advance the technology of water supply, use, processing, recycling, and recharge.

Clearly, the amount of water drawn from streams, water bodies, and well fields must be reduced and brought into balance with sources of replacement. The area of irrigated agricultural land must be reduced—phased out instead of expanded as presently. It is to be permitted only where freshwater is abundant and can be used without depletion of local and regional reserves. This must be a factor also in the allocation of development sites of all types.

Priority attention is to be given to reducing the vast areas of mowed and irrigated residential lawns. The American homeowner’s dream seems to be that of widely spaced single-family homes fronted or surrounded by as much closely shorn and well-watered green lawn as possible. With both land and water now at a premium, we must look to smaller lots, attached homes, and multifamily apartment living with lawn areas confined to walk borders, game courts, and other specialized areas.

With wise land use planning and water resource management, we can have in the United States an adequate supply of freshwater for centuries to come.

Possibilities

If there may be problems, there are possibilities also. These include the preservation of those areas of wilderness or wild river yet unspoiled. They include the conservation and compatible uses of those water-related areas which are rich in soils, cover, or scenic quality and which in their natural or existing state are important contributors to our ecological well-being. The possibilities include the restoration of depleted farmlands and dilapidated urban wastelands to productive use by regrading, soil stabilization, and replanting of eroded slopes and slashings. Well-planned agricultural districts, recreation lands, towns, and cities could then be clustered within a green-blue surrounding of field, forest, and clean water, linked with parklike transportation ways. Far more than many may realize, we are already well on our way to such a concept, and ethic, of land and water management.

Ecologically managed wetlands are rapidly becoming an important alternative to conventional wastewater treatment systems.

Proficient land and site planning will help solve the water-related problems and ensure that the possibilities are fully realized. The level of performance should be continually improved in the light of increasing public support and advancing technology. It is quite possible that within the span of our lifetimes wide reaches of our land and waterways may be restored to the fairer form that our naturalist friends Thoreau, Muir, and Aldo Leopold once found so exhilarating.

In considering the site development of any landscape area, a first concern is the protection of the surface and subsurface waters both as to quality and as to quantity. Quality is maintained by precluding contamination in any form, as by the flow or seepage of pollutants, by groundwater runoff charged with chemicals or nutrients, by siltation, or by the introduction of solid wastes. The assurance of acceptable water quantity is largely a matter of retaining surface runoff in swales, ponds, or wetlands to prevent the flooding of streams or water bodies, to sustain the level of the underlying water table, and to replenish the deep-flowing aquifers.

Utilize

Since propinquity to water is so highly desirable, since there is only so much water area and frontage to go around, and since the protection of our water and edges has become so critical in our environmental planning, it would seem reasonable that all water-oriented land areas should be planned in such a way as to reap the maximum benefits of the water feature while protecting its integrity. This goal often resolves itself into the simple device of expanding the actual and visual limits of water-related land to the reasonable maximum. This is not as difficult as it might seem.

Avoid the water-edge ring of roads and buildings that seal off water bodies and limit their use.

By expanding the traffic-free lake environs to include park, wildlife preserve, and public areas as well as private cottages and resorts, the use and enjoyment of the lake (and surrounding real estate values) are enhanced.

In practice, the rim of frontage is extended landward from the water edge in such a manner as to define an ample protective sheath. This variform vegetated band, at best following the lines of drainage flow and responding to the subtle persuasions of the topography, will provide frontage for compatible development and serve as access to the water. The possible variations are limitless, but the principle remains always the same. Each variable diagram must stand the test of these three underlying conditions:

- All related uses are to be compatible with the water resource and landscape.

- The intensity of the introduced uses must not exceed the carrying capacity or biologic tolerance of the land and water areas.

- The continuity of the natural and built systems is to be ensured. If these three principles are adhered to, it can be seen that all land-water areas, from homesite to region, can be planned and developed in such a way that both the scenic quality and the ecologic functions are maintained.

As a breakthrough in the treatment of wastewater and toxic effluents it has been discovered that ecologically engineered wetlands can be devised to extract and retain the contaminants while storing the clarified water and providing habitat.

Open water is fast disappearing from the American scene. Expanding agricultural lands and development continue to follow the drainage ditches and tile fields across prairie wetlands and everglades. The urgent compulsion to dredge and fill, while slowed by recent conservation legislation, continues to reclaim the marsh, the cedar bog, and the mangrove strands. Rivers, lakes, and oceanfront are being hidden from public view and shielded from public access by a rising wall of apartments and office towers.

Is it not too late.

It is not too late!

Protect

Where water features exist, protect them. Work to preserve not only the open water but the supporting watershed covers, the natural holding ponds, the swampland, the floodplain, the feeding streams, and the green sheath along their banks. To be protected as well are the coastal wetlands, the landward dunes, and the outward reefs or sandbars.

In the planning of every water-related project site there is an opportunity to demonstrate sound management principles. Each well-designed example not only serves the interest of the client but also stands as a lesson to others.

Rediscover

Many water features of great potential landscape value have been bypassed in the process of building or roadway construction. They remain “out back” or “yonder,” often in their natural state, more often as silted or polluted drainage sumps or dump sites. They are waiting to be reclaimed by the community as parkland or open space preserves. Preserved or modified, they may be rediscovered and featured in new public or private landscape development.

Restore

Again, a spring, a pond, or a section of stream may have been enclosed in a culvert or buried in fill. Or it may have been used as a dumping ground and covered with brush and trash. Sometimes, to add to the disgrace, such water features have been shamefully polluted with oils and chemicals and are coated with scum. In most urban and suburban precincts and often in the open countryside, there are to be found such unrecognized landscape treasures waiting to be reclaimed.

Xeriscape landscape construction, planting, and gardening is that requiring a minimum of irrigation.

Constructed wetlands. Phillips Farevaag Smallenberg, Photo taken by Jim Breadon

Conserve

The alarming drawdown and depletion of our freshwater reserves underscores the need for new attitudes toward water use and resource management. Even in times of moderate drought, many city reservoirs are emptied. While in most parts of the world water is considered a precious commodity and used sparingly, in the United States it is squandered as though the supply were unlimited. It is not.

Only in America with its abundance of buildable land and fresh water has it been the fashion to surround single-family homes and apartments with irrigated lawn. With land and water supplies in short supply it will no longer be affordable or acceptable.

To conserve our diminishing supply in the face of ever-increasing demands, several courses of action are proposed:

Limit consumption.

Regulate household use by sharply escalating the rates on a sliding scale for use above a basic norm.

Preclude use of well water for irrigation.

Lawns cover over fifty thousand square miles of the surface of the United States—an area roughly equal to Pennsylvania, and larger than that occupied by any agricultural crop.

Wade Graham

Recycle wastewater. In urban areas this suggests a dual system of water supply—one for drinking, cooking, and bathing, the other for all other purposes. Treat and sanitize wastewater (at a much lower unit cost) to be used exclusively for irrigation, air-conditioning, street washing, and industrial processing.

Replenish

In undisturbed nature, the subsurface water reserves are sustained automatically—by the retention and soil filtration of precipitation. When trees, grasses, and other vegetative covers are removed—and especially when replaced by paving or construction—the water tables are thereby lowered.

Three feasible remedies are suggested:

- Protect and replant the upland watersheds.

- Restore the natural drainageways (to the 50-year flood stage) to public ownership or restricted private use, and sheathe them in vegetation.

- Require of new development that the storm-water runoff be retained in catchment basins, swales, or ponds, for percolation and aquifer recharge.

Preplan

Sometimes in the necessary process of mining or in the excavation of open extraction pits, there exists the need to create new water areas. From the air in some regions these can be seen to dot the landscape, usually in the form of dull rectilinear dragline creations. Each may now be recognized as a lost opportunity. With advanced planning and sometimes little additional cost, these pits and the bordering property area could have been, and yet can be, shaped into new and attractive waterscapes, with free-form lakes, grassy slopes, and tree-covered mounds. This reasonable preplanning approach, as a condition of obtaining excavation permits and combined with soil conservation and afforestation, provides the opportunity to preclude new scars on the countryside and, instead, to create new landscapes from the old. With enterprise, many existing extraction pits could be acquired, reshaped, and transformed into highly attractive and valuable real estate.

Use of native vegetation conserves water. © D.A. Horchner/Design Workshop

In the development of land-water holdings, special care is required in the delineation of use areas, in the location of paths of vehicular and pedestrian movement, and in site and building design.

Natural Streams and Water Bodies

Where these exist, they represent the resolution of many dynamic forces at work—precipitation, surface runoff, sedimentation, clarification, currents, wave action, and so forth. It can be seen that to alter a natural stream, pond, or lake will set in motion a whole chain of actions and interactions that must then be restored to equilibrium. It is soon learned, therefore, that a first consideration in the site planning of water-related areas is to leave the natural conditions undisturbed and build up to and around them.

For safety, a beach should slope to a depth exceeding a swimmer’s height (6 feet plus) before reaching a deep-cut line.

In their existing state, the banks of streams and rivers are lined by a fringe of grasses, shrubs, and trees that stabilize soils and check the sheet inflow of surface storm water drainage. The bank faces are held in place by stones, logs, roots, and trailing plants that resist currents and erosion.

Lakeshores and beaches, armored with wave-resistant rock or protected by their sloped edges of sand or gravel, are ideally shaped to withstand the force and wash of wind-driven waves. Even the quiet pond or lagoon is edged with reeds or lily pads, which serve a similar purpose.

Where a water feature such as a spring, pond, lake, or tidal marsh occurs in nature, it is usually a distillate of the surrounding landscape and a rich contributor to its ecologic workings and the scene. Such superlatives are to be in all ways protected. This is not to preclude their use and enjoyment, for the purpose of sensitive planning is to ensure protection while facilitating the highest and best use of the landscape feature.

Rectilinear excavation pits can be reshaped by supplementary grading to create free-form lakes.

Canals and Impoundments

Parts of the American landscape are laced and interlaced with a network of canals. Some have been in operation since colonial times. Many have been long abandoned. When “rediscovered” and reactivated in rural or urban settings, these waterways, with hiking or biking trails alongside, become treasured community features. All are to be preserved and protected.

At a miniscale, a trickling rivulet can be impeded by a few well-placed stones to increase its size and depth. By the construction of a proper dam, larger and deeper pools can be created for fishing, swimming, or boating or as landscape features.

Ocean beaches are built and rebuilt by the forces of currents, storms, and tides. They are essentially temporary, since the forces that built them can also alter them beyond recognition—sometimes during a single great storm. Even the most costly stabilization projects have proven ineffective against.… beach evolution.

Albert R. Veri et al.

At a greater scale, huge reservoirs or lakes may be impounded for water storage, flood control, or the provision of hydroelectric energy. Provided the drawdowns are not too severe or frequent, such large impoundments offer the opportunity for many forms of water-related recreation and often become the focal attraction for extensive regional development. To ensure their maximum contribution and benefits, all major reservoirs and the contiguous lands around them should be preplanned before construction permits are issued, with dedication provided for necessary rights-of-way and for appropriate public and private uses.

Often, and particularly in large parks and nature preserves, the migratory aspect of beaches and shores is acknowledged, and they are allowed full freedom to assume and constantly adjust their natural conformation. This eminently sound approach deserves far wider application.

From the smallest dam to the largest, the location must be well selected to ensure its stability, for a failure and surging washout can bring serious problems downstream. Water levels are to be studied in relation to topographical forms so that the edges of the pond or lake may create a pleasing shape well suited to adjacent paths of movement, use areas, and structures.

Where the feeding streams are silt-laden or subject to periodic flooding, upstream settling basins with weirs and a gated bypass channel will be required.

The water in many city reservoirs is hidden from public view. In its storage and processing it could be used to refresh and beautify urban surroundings.

Paths, Bridges, and Decks

People are attracted to water. It is a natural tendency to wish to walk or ride along the edge of a stream or lake, to rest beside it enjoying the sights and sounds, or, in the case of streams, to cross to the other side.

These desires are to be accommodated in site planning. Routes of movement will be aligned to provide a variety of views and will in effect combine to afford a visual exploration of the lake or waterway. It is fitting that water-edge paths or drives be undulating in their horizontal and vertical curvature and constructed of materials that blend into the natural scene. At points where water-oriented uses are intensified or where the meeting of land and water is to be given more architectural treatment, the shapes and materials of the pathways and use areas will become more structural, too.

Ribbon path at river’s edge. Kongjian Yu/Turenscape

Overlooks may be as unprepossessing as a bench in the widened bend of a path. Or they may be decked, terraced, or walled, to bring the user into the most favorable relationship to the water for the purpose intended, be it viewing, relaxing, fishing, diving, or entering a boat.

Bridges, too, are designed with regard for much more than basic function. At their best they provide an exhilarating experience of crossing. Seen from many directions and angles, they are to be given sculptural form. Every bridge is to be designed with utmost simplicity as a clear expression of its materials, structure, and use. Each will derive distinctive character from the locality and the nature of the site.

Water Edges

The meeting of land and water presents a line of special planning significance.

It has been noted that where the uses are mild and where the banks or shores are attractive, they are best left essentially undisturbed. As water-related uses are intensified and the need for space increased, the degree of edge treatment is correspondingly increased until in some instances it may become entirely architectural.

Water’s edge in urban environment. Tom Fox, SWA Group

In the shaping of water bodies it is desirable that the outline be curvilinear, rather than angular, to reflect the undulating nature of water.

Often, to provide more efficient use of the bordering land, the pond or lake is first excavated along straight lines, which are often softened by curvature and by rounding intersections.

Since in most methods of excavation, as by dragline or pans, straight, deep cuts are more economical, the central body of a lake is often a rectangle or a polyhedron in shape, with a widened perimeter shelf sloped to the deeper excavation pit and trimmed to more natural form.

From no point along the shore should the expanse of the water surface be seen in its entirety. If possible, the shoreline should be made to dip out of sight at several points to add interest and to set free the observer’s imagination. By this design device not only is the water body made more appealing, but its apparent size is increased.

In water-edge detailing these are some of the fundamentals to be kept in mind:

- Minimize disruption. Where the banks or shores are stable, the less treatment, the better.

- Maintain smooth flows. Avoid the use of elements that obstruct currents or block wave action.

- Slope and armor the banks, if necessary, to absorb energy where flows are swift or wave impacts are destructive.

- Provide boat access to water of desired depth by the use of docks, piers, or floats with self-adjusting ramps.

- Avoid the indiscriminate use of jetties and groins or the diverting of strong currents. The effects are often unpredictable and sometimes calamitous.

- Design to the worst conditions. Consider recorded water levels and the height of wind-driven surf.

- Preclude flooding. Hold the floor level of habitable structures above the 50-year-flood stage as a minimum.

- Promote safety by the use of handrails, nonslip pavement, buoys, markers, and lights.

- Use weather- and water-resistant materials, fastenings, and equipment. Corrosion and deterioration are constant problems along the waterfront.

- Prevent the flow of polluted surface runoff into receiving waters. Such runoff should be intercepted and treated, or filtered by the use of detention swales.

The qualities of water are infinite in their variety.

In depth, water may range from deep to no more than a film of surface moisture.

In motion, from rush to gush, plummet, spurt, spout, spill, spray, or seep.

In sound, from tumultuous roar to murmur.

Each attribute suggests a particular use and application in landscape design.

Pools, Fountains, and Cascades

It is hard to imagine any planned landscape area—patio, garden, or public square—that would not benefit by the introduction of water in natural or architectural form. Its sound, motion, and cooling effects give it universal appeal.

Inside the cascade. Barry W. Starke, EDA

Landscape Architect M. Paul Friedberg and Partners

Fountains add interest and refreshment. Belt Collins; © 2012 Bruce Forster Photography-All Rights Reserved; Belt Collins; Barry W. Starke, EDA; ©2003 AECOM/Photography by Dixi Carrillo; Kongjian Yu/Turenscape

Water has become symbolic. It connotes and promotes refreshment and stimulates verdant growth. Its presence can convert seeming desert into seeming oasis.

Where water is plentiful and its use is to be featured, as in urban courts, malls, or plazas, its treatment is often carried to an exhilarating scale and high degree of refinement. Many a city is remembered for the delight of its exuberant fountains and rushing cascades.

In even the smallest garden also, water has its essential place. Wherever plants are used, for example, irrigation is needed and is to be considered in the design. A trickling spout or well-placed spray can moisten and cool a patch of gravel mulch, a bed of ivy, or a square of sunlit paving. The simplest container of water placed out for the birds adds interest and refreshment, as does a quiet pool, a dripping ledge, or a splashing fountain. Such water features, easy to devise and construct, can yield long hours of watching and listening pleasure.

Water’s symbolic journey from mountain to sea. Barry W. Starke, EDA