The word community has many connotations, most of them favorable. For people, like plants and animals, seem to flourish in shared and supportive groupings. What is the nature of such planned community groupings, and how are they best formed?

Historically, people have banded together for some compelling reason, as for protection within the gated walls of the medieval city or the palisade of the fort. They have formed communities to engage in farming, commerce, or industry or to pursue their religious beliefs. In the opening up of America, settlements grew spontaneously around harbors and river landings, at the crossings of transportation routes, and wherever natural resources were concentrated or abundant.

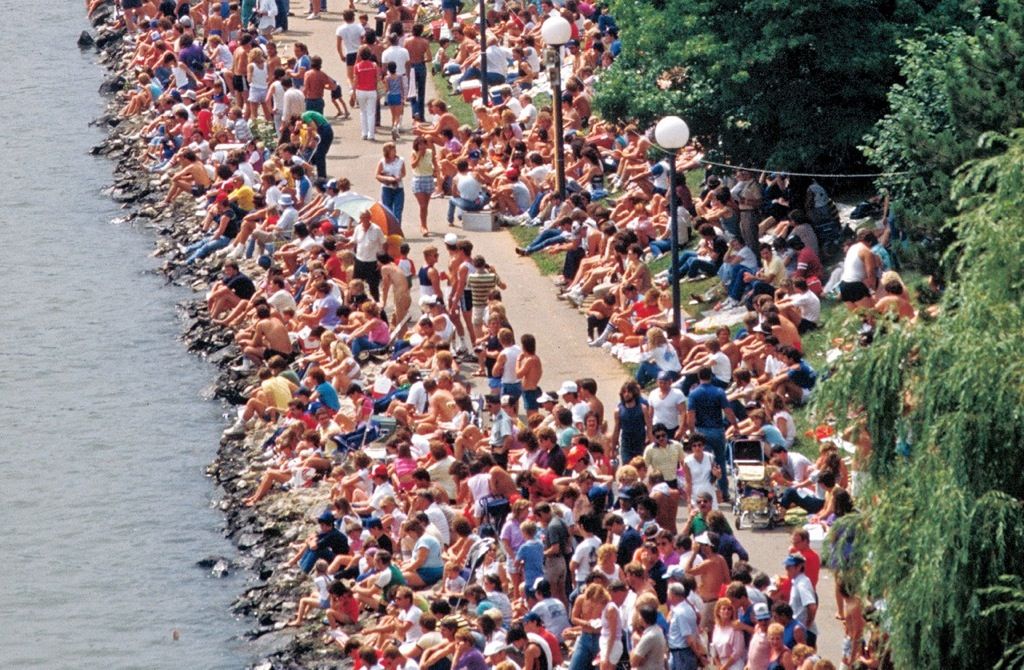

Within communal aggregations, friendships have been made mainly on the basis of propinquity. Dwellings were built in the most favorable and affordable locations, and then families moved in to make friends or sometimes to feud with the folks next door. Social groupings and working alliances were for the most part accidental. Homes were permanent, and neighborhoods were relatively stable. Towns and cities proliferated—too often in patterns of squared-off streets. Residential districts became impacted, often without schools, conveniences, or open-space relief. As densities and traffic increased, time-distances became greater, pollution often became intolerable, and surrounding fields and woodlands melted inexorably away.

Any consideration of the future of open space, such as exists between our urban centers, requires a thoughtful appraisal of one of our most voracious consumers of land: housing. Man’s preference in housing, especially in urban fringe areas, results in the sprawl of single detached units in an awesome continuum across the countryside.

What is the origin of the desire for this type of shelter expression—this compulsion to flee the city and to build cube on cube across the open land? Is it a desire for tax relief? Vested equity? Breathing space? Contact with the land? Or the poetics of “Home Sweet Home”? Regardless, is the solution largely that of better design within the acceptance of this preference? Or change from separated horizontal forms to unified collective density patterns? Perhaps as space between units decreases, space between our urban centers may be preserved, or may increase.

Walter D. Harris

With the coming of the twentieth century and the advent of the automobile, the farm-to-city movement was suddenly reversed. Initially a few of the wealthy fled the industrial city to build romanticized farmsteads and rusticated villas such as those along the Hudson River. They were soon joined by many members of the middle class, to whom social reform was bringing an improving standard of living and newfound mobility. These families shared the beckoning dream of a better, more fulfilling life out beyond the city outskirts, where they could live amid forest, fields, and gardens in communion with nature. As they surged outward in ever-increasing numbers, the new suburbia was born. It was to become an American phenomenon. New types of dwellings would be designed, and innovative community patterns would be created. The subdivision tracts, planned communities, and new towns gradually evolved and are still evolving. If they fall somewhat short of the vision, it is because they have destroyed too much of the nature that they sought to embrace. It is because they have carried along with them from the city too many of the urban foibles—the bad habit of facing homes upon traffic-laden streets instead of pleasant courts or open-space preserves, of inexplicably lining schools, churches, and factories haunch to haunch along the roaring highways. It is because we have allowed the interconnecting roadways to become teeming thoroughfares along which has coalesced mile after mile of crass, traffic-clogging commercial-strip development. It is because we still have much to learn about the basics and intricacies of group living, of land use, and of transportation planning.

Without controls, unsuitable uses infiltrate residential areas. Widened streets and highways draw to their sides commercial-strip coagulations that reduce their carrying capacity and restrict the traffic flow. Deterioration and blight are rampant. Vacant structures are vandalized. Property values plummet, and the solid citizens of the original homes move out if they can. Sadly, wherever they go to start anew, without better planning and regulation, the cycle will be repeated. It need not be so.

Monotony

Too often in suburban development a well-wooded site is leveled, the trees and cover destroyed, the streams and drainageways encased in massive storm sewers or open culverts. Look-alike houses are then spaced out in rows along a geometric checkerboard of streets. A new flora of exotic plants is installed in the hard-packed ground. The native fauna—the furred and feathered creatures of the wood and meadow—take off to seek a more livable habitat.

The subdivision as we know it is a typical United States invention, with few counterparts in Europe or Asia.

Variety, the antitheses of monotony, can be preserved and attained by sensitive land and community planning, with far more resident appeal and at far less initial and continuing cost.

Inefficiency

The well-planned neighborhood or community—urban, suburban, or rural—should function as an efficient mechanism. This is to say that energy and materials are to be conserved and frictions eliminated. Energy conservation suggests that things and services needed—schools, shopping, and recreation—should be convenient, easy to reach, and close at hand. Yet in some neighborhoods many blocks must be traveled and many streets crossed in order to buy a quart of milk or a loaf of bread. Playgrounds and even elementary schools can be reached only by braving a grid of rushing trafficways. As we know from reading the papers, some children and adults never make it.

Most contemporary shopping centers are inaccessible by foot. Barry W. Starke, EDA

In a planned community, by comparison, dwellings of all types are clustered around the activity centers. Access by foot, bicycle, or electric cart is via traffic-free greenways. Safer. More pleasant. Far more efficient.

The alignment of homes and apartment buildings along roadways and streets was for years the accepted procedure. It is no longer considered desirable. Few families would opt for a home that faced upon a busy trafficway if offered the alternative of off-street courtyard living. Offset residential groupings not only provide more salable and rentable housing, they do so more economically. Further, the efficiency of the passing street is increased by the elimination of curbcuts at every driveway, with the intrusions that these imply.

With clustered off-street housing, the high cost of street and highway construction with its trunkline sewers and utility mains can be shared by many more dwellings. Single- and double-loaded streets are not only uneconomical, they are fraught with all sorts of problems.

The common practice of constructing sewers, utility mains, and energy distribution systems within the street right-of-way is another source of recurrent difficulties. Power poles and overhead wires interfere with street tree plantings which must then be periodically mutilated to keep the lines clear. Beyond that, it is patently impractical to tear up a section of pavement and close a lane, if not the whole street, for the installation of each new service lateral—or for the seemingly endless repair or enlargement of in-street water, gas, or sewer mains. Far better that a utility easement be reserved along rear property lines to leave the streetscape unscathed.

In many unplanned communities the greatest waste is in uncalled-for and destructive earthwork and unneeded storm-sewer construction. These costs are incurred because the site layout runs counter to the topography. Natural covers protect and stabilize the soils and slopes. Natural drainageways and streams carry off the excess precipitation. But with the vegetation destroyed and the drainageways blocked, the heavy expense of resultant drainage structures and soil stabilization must be factored into the cost of each dwelling. Not to mention replacement plantings.

Radburn, New Jersey, 1928. This revolutionary concept of community living was devised by its planners, Henry Wright and Clarence Stein, as an answer to living with the automobile. Homes were grouped in superblocks with automobile access from cul-de-sac streets precluding high speed through traffic. Pedestrian walkways, free of automobile crossings, provided access to large central park areas in which and around which were grouped the community social, recreational, and shopping centers.

In this plan concept were sown the seeds of ideas that have sprouted in most of the superior neighborhood and community plans of succeeding years.

In the home-building and community development industries—profit motivated and highly competitive as they are—it is indeed fortuitous that the most successful entrepreneurs have learned that well-conceived and well-built projects are not only more efficient, they are more environmentally sound, more people-friendly, more salable or rentable, and more profitable.

Unhealthful Conditions

Mens sana in corpore sano. A sound mind in a sound body. What has community planning to do with the state of one’s health?

If we are, as it is said, largely the product of our heredity and our environment, then let us hope that we come of hardy stock, for living in neighborhoods that are obsolescent, polluted, and/or traffic-fraught is hardly conducive to health.

Mental well-being derives from rational order and behavior. When living conditions are clearly unreasonable; when the daily experience is one of frustration, anxiety, or disgust, it is hard to maintain a positive state of mind.

As to behavior, we live in a revved-up society that our parents could not have imagined. In our crowded lives everything is done at double speed and driven intensity. Between spates of whizzing about to keep up the pace, we spend long hours in sedentary occupations. Much of the working day is spent hunched over the desk, counter, or machine—or staring into computers. We are detached from the wholesome reality of the field and furrow, the woodlot, the vineyard, the creatures of the barn and dooryard that kept our forebears sane and healthy. Can our planned communities of the future provide the antidote, the counterpoint, to such mechanistic living? Can we find in our new neighborhoods the opportunities for healthful outdoor exercise and recreation, for group activities and fulfilling communal life? It is believed so.

Danger

Who could deny that our present communities, as most of us experience them, pose danger to life and limb?

The street crossings and trafficway intersections

The mix of people and vehicles

Overhead power lines

Toxic levels of soil and water contamination

The polluted air that we breathe …

In addition, there’s the increasing threat posed by crime in our streets and alleys—the weekly muggings, break-ins, or drive-by shootings. These are endemic to obsolescence and vacancies, to unlighted lurking places—and as well to the lack of better places to be and better things to do.

All these potential and very real dangers are subject to planned improvement.

As we set out to plan the more salubrious neighborhoods of the future, wherein lie the possibilities? It is proposed that they will have:

A better fit of construction to the land

A better fit of homes to related trafficways

A better fit of homes to homes and homes to activity centers

A rich variety of things to see and do

Freedom of individual expression and innovative improvement

A shared sense of true community, of compatible living together.

Building Arrangements

Why do houses face upon streets? “Because,” some might say, “they always have.” Probably such respondents are right, for we humans are slow to accept any change, even when the advantage is obvious. Until recently, in the United States it was uniformly a legal requirement that all platted homesites be dedicated with frontage upon a public right-of-way. As a consequence, homes sprouted row upon row along streets and highways across the countryside. This posed few serious problems as long as the roads were used by horses and horse-drawn carriages, wagons, and carts.

Then came the automobiles. They came, and came, and they keep on coming. The roadways are overwhelmed. They have been widened and lengthened until today the trafficway network covers most of the landscape like a coarsely woven mesh. Meanwhile, buildings continue to crowd alongside the pulsing motorways. Communities are thus cut apart—divided and subdivided again by lines of fast-moving traffic. This makes little sense for either the residents or the motorists.

In seeking solutions to the dilemma, land planners have sought to have the frontage requirement rescinded. Where this has been accomplished it has produced building-road relationships that hold much promise.

One fairly recent advance is that of planned unit development, or PUD as it is now commonly called. A PUD ordinance, where enacted, provides that in the planning of sizable residential tracts, incentives are given for creative site planning. While the types of permitted land uses and the total land coverage and density limits are fixed, the more restrictive provisions of long-obsolete codes no longer govern. New mixes of housing types and traffic-free neighborhoods are encouraged. Clustering and shared open space are consistent features, together with built-in convenience and recreation centers. The resulting communities and new towns have demonstrated the many benefits of off-street residential groupings and pointed the way to new concepts of true community living.

Separation of pedestrian and automobiles in planned community. Robinson Fisher Koons

Access and Circulation

If the new residential areas are to be traffic-free, what of the automobile? It is to be assumed that driver-operated vehicles in one form or another will long be a favored form of transportation. This will be even more so when the paths of vehicular movement are freed of the myriad pedestrian crossings and hazardous intersections, when arterial roads and circulation drives are designed as free-flowing parkways with no on-grade intersections and widely spaced points of access or egress.

Communities will no longer be cross-hatched with roads and streets but will instead be planned as a series of sizable pedestrian domains of various types, fitted to the topography. Each will be bounded and interconnected by nonfrontage circulation drives. Each neighborhood, and the larger community, will be accessed by vehicles from the outside with inward penetration to residential parking courts and service compounds. Pedestrians and vehicles will thus be separated—each with their own specially designed areas of operation. Neighborhood living will then be safer and more pleasant, and vehicles can move at sustained speeds without interference.

Schools, shopping, and recreation centers are the main community destinations. In many of the early planned communities they were intentionally isolated from single-use residential groupings. In one area were placed the look-alike single-family homes, at another the look-alike town houses, and elsewhere the look-alike apartments. In such sanitized residential conclaves there was little of interest to see or do—except at the distant school, playground, or shopping mall. As a result, the housing neighborhoods were overly quiet to the point of being boring.

In the more recent mixed-use planned communities, housing units of varying types are grouped closely around the activity centers. Not only is access more easy, but this lively, more democratic mix affords welcome variety and increased opportunity for neighbor-to-neighbor meetings and friendships.

In such freely composed, more compact, and focalized residential groupings the activity hubs and nodes get more use, as do the interconnecting paths of pedestrian movement. Especially if the places are made more attractive with plantings, lighting, and such furnishings as fountains, sculpture, and banners. And if the ways are pleasantly aligned and enhanced with mounding, trees for shade, benches, and perhaps here and there a bike rack or a piece of child’s play equipment.

In most of the more PUD developments, homes and apartments are arranged in compact groupings or clusters to squeeze out wasted separation space around and between the buildings. This is not only more land- and cost-efficient, but also, with the same overall densities, yields an increased measure of shared open space.

This compaction is evident also in the better activity centers. Both at the neighborhood and community levels, compatible uses are combined. Examples include the elementary school and park; the high school, game courts, and athletic field; the shopping, business, and professional office complex; the community building, church, library, and performing arts assemblage; or the museum and center for arts and crafts. In all such cases the intensification is beneficial. Moreover, the gathering together of once dispersed uses into more vibrant nucleii also provides in the overall community plan additional open area.

Open Space

Why community open space? Because without it there can be little sense of community. It is mainly in the outdoor ways and places that communal living takes place.

Community park and open space. Tom Fox, SWA Group

Open space equates with many forms of recreation. Some, like lacrosse or field hockey, require expansive areas. Others need only limited space. A child’s slide or a basketball backstop, for instance, will fit almost anywhere. Baseball fields and basketball courts need precise orientation and construction, while more passive kinds of recreation—picnicking, kite flying, or playing catch—take little more than an open field. Lineal spaces, as for jogging paths, health trails, or bikeways, must be carefully woven into community plans to ensure continuity.

Open space has other values, too. If it follows and envelops the drainageways and streams, it serves to preserve the natural growth and define buildable areas with lobes of refreshing green. It also provides cover for birds and small animals that contribute much delight to the local scene, not only in the suburbs but in the inner city as well.

Where does such open space come from? As noted, it is a natural product of the PUD planning approach which, with fixed densities, features clustered building arrangements. Available open spaces include the unpaved areas of the street rights-of-way—or the whole of utility easements. They are acquired in part as segments of park and recreation systems. Unbuildable areas such as floodplains, marshes, steep slopes, and narrow ridges make their contributions, as do the open areas of business office parks, the university campus, and institutional grounds. Some highly desirable open space may be derived from the reclamation of extraction pits, landfills, strip-mining operations, cutover timberlands, or depleted farms. Public agencies such as the Department of Transportation, water management districts, or the military may transfer excess or vacated holdings. Again, prime lands may be donated by foundations or by private citizens, with or without the incentives of tax abatement. And there are, too, the possibilities of scenic and conservation easements.

Piece by piece, parcel by parcel, an open-space system can in time be fitted together for the good of all concerned—provided that for each community there is a program and a plan.

New Ethic in Community Planning: P-C-D

Preserve the best of the natural and historic features.

Conserve, with limited use, an interconnecting open-space framework.

Develop selected upland areas with site-responsive building clusters.

By this approach the project site is thoroughly analyzed by a team of qualified planning experts and scientific advisers. Then on the topographic surveys a line is drawn around those areas of high scenic, historic, or ecological value (P). These areas and features are to be preserved intact, without significant disturbance. Around them, as protective buffers, are then described conservation swaths of lesser landscape value. The conservation (C) areas may be devoted to limited open space or recreational uses that will not harm their natural quality. Development (D) or construction areas are only then allocated on the receptive higher ground. Here the structures are usually clustered in more compact and efficient arrangements within the blue and green open-space framework. Here, without inflicting negative impacts, people can live and work at peace with their natural surroundings.

Many conservationists who would protect and assure the best use of our lands and waters have yet to learn that cooperative, large-scale, long-range planning is more effective than the common no-growth tactic of “block and delay.”

A planned community using the P-C-D approach (Pelican Bay, Collier County, Florida). Beach, dunes, and tidal estuary preserved. Wetlands, waterways, and native vegetation protected (conserved). Clustered development on the upland, within an interconnected open-space frame. All work well together. Ed Chappell, Inc. EPD

Planned communities are prime examples of sound economic development coupled with conservation. Yet even the most glowing examples have come into being only after long years of battle with outmoded codes and with self-styled environmentalists, who by all reason should be the greatest advocates. For mile after mile of beachfront and thousands upon thousands of acres of prime forest and wetland have already been set aside and preserved intact, voluntarily, by comprehensive community planning.

A planned community with golf course as open space. Tom Lamb, Lamb Studio

Much can be accomplished when this process comes to be carried forward in full cooperation with local citizens, dynamic conservation groups, and contributing public agencies. It can be seen that such P-C-D planning applies not only to residential development, but to every type of use and parcel—to whole regions and to the larger state.

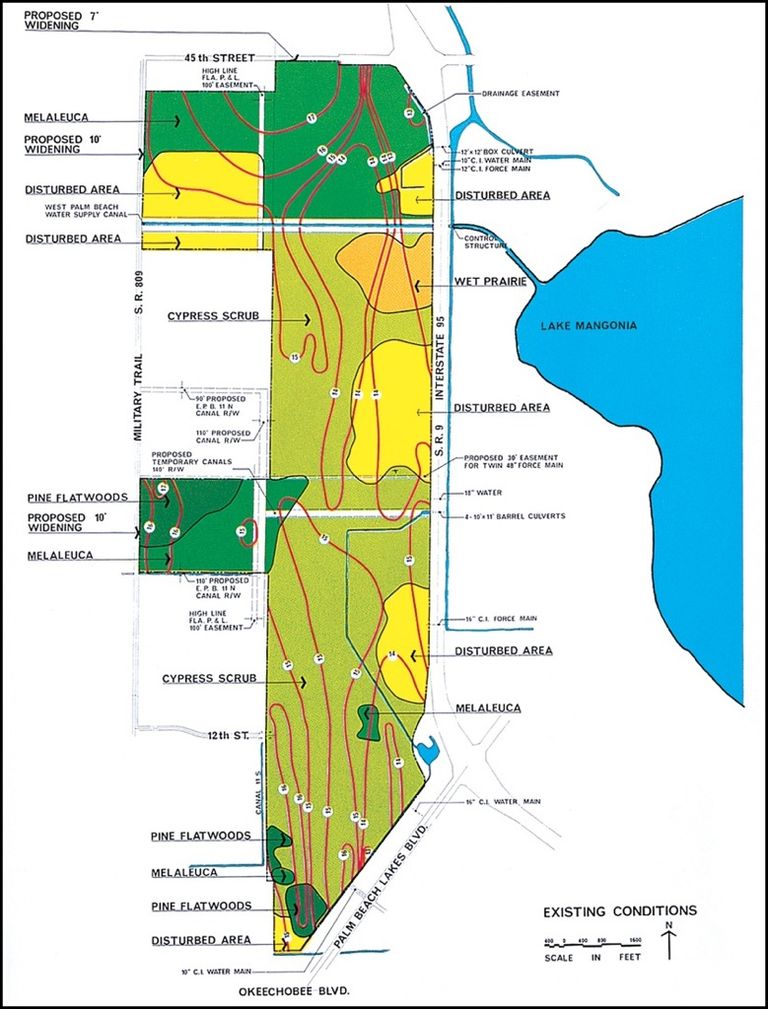

Existing site conditions. EPD

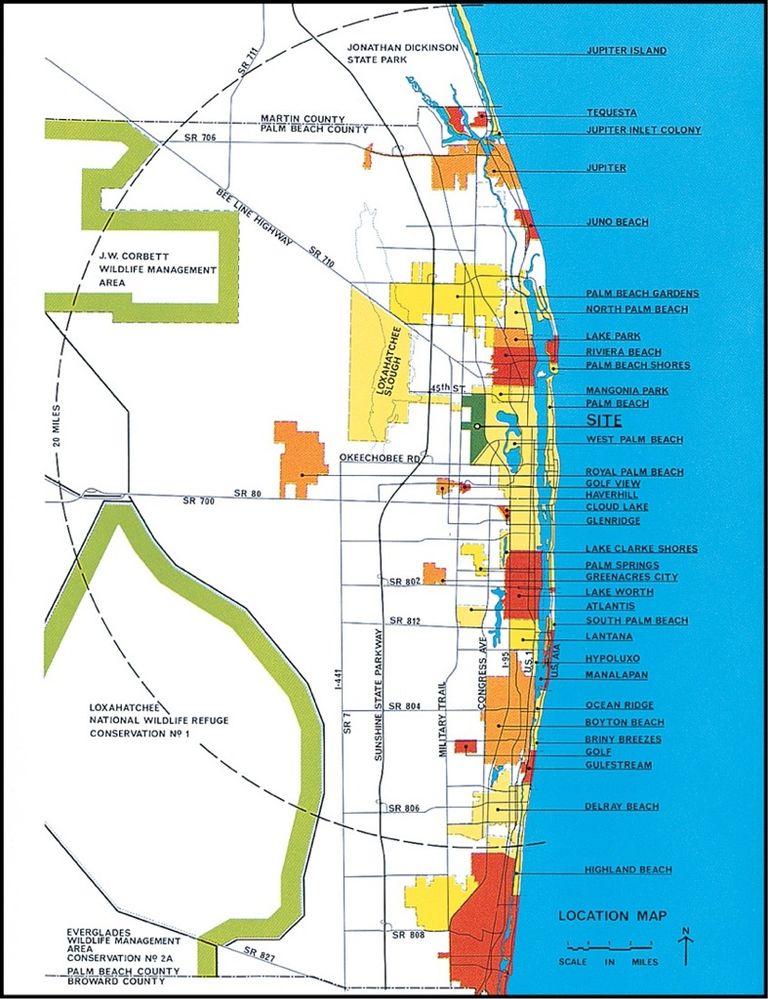

Regional framework. EDP

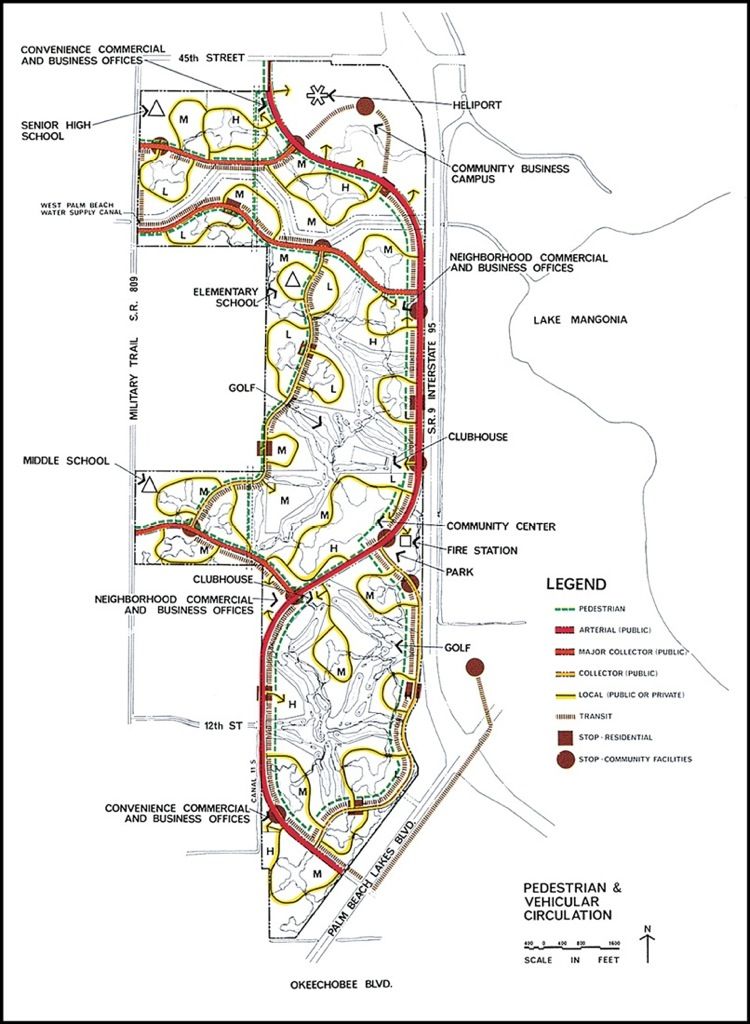

Circulation patterns. EDP

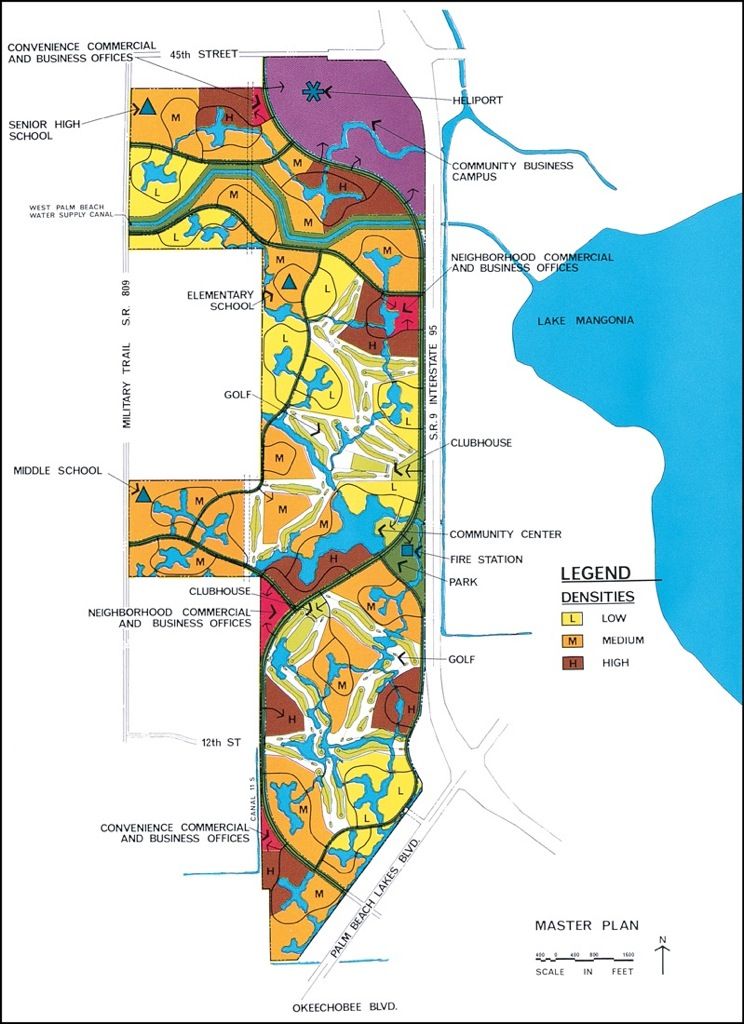

Conceptual community plan. EDP

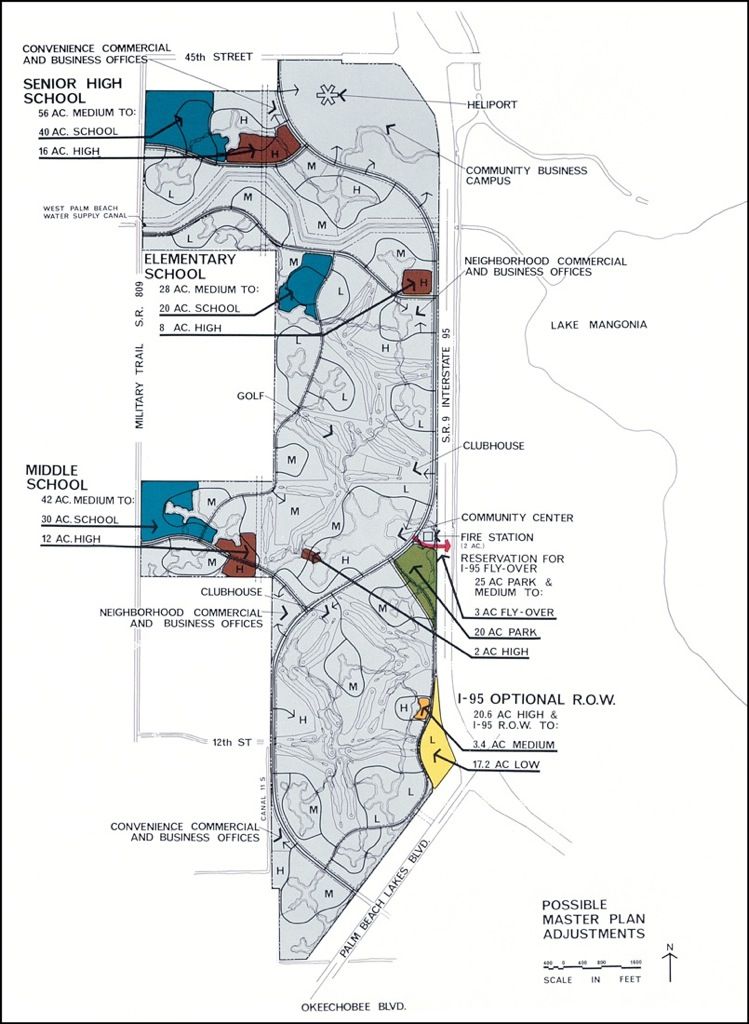

Flexibility: Possible plan adjustments. EDP

In appraising the better examples of recently planned communities we find many promising features. Some planning concepts, like the transfer of development rights and flexibility zoning, were unheard of even a few years ago. Some have met with immediate acceptance, others have not, and still others have yet to be adequately tested. While some approaches have failed in their initial application, they may contain the seeds of ideas that will flower in the communities of the future.

All good planning must begin with a survey of actual resources: the landscape, the people, the work-a-day activities in a community. Good planning does not begin with an abstract and arbitrary scheme that it seeks to impose on a community; it begins with a knowledge of existing conditions and opportunities …

The final test of an economic system is not the tons of iron, the tanks of oil, or the miles of textiles it produces: The final test lies within its ultimate products—the sort of men and women it nurtures and the order and beauty and sanity of their communities.

Lewis Mumford

With the transfer of development rights, owners of ecologically sensitive or productive agricultural land may negotiate with planning officials a trade-off by which the right to develop the prime landholding is forfeited in exchange for the right to develop a similar, or different, type of project at an alternative location. Often by such an arrangement a valuable community asset can be preserved and extensive tracts of marginal or depleted property transformed into highly desirable real estate. Everyone thus benefits.

Fine communities seldom if ever just happen. They must be thoughtfully and painstakingly brought into being. Improved approaches are continually emerging and give new meaning to such words as housing, health, education, recreation, and community. In the shaping of our more advanced residential areas the following principles are being successfully applied.

Apply the PUD approach. Planned unit development (PUD) is a rational framework for the phased development of community plans. Essentially, it establishes at the start the types of uses to be included, the total number of dwellings, and a conceptual plan diagram. The traditional restrictive regulations are waived, and each successive phase as it is brought on in detail is checked against the conceptual plan and judged solely on the basis of foreseeable performance.

Request flexibility zoning. For larger tracts, this permits within the zone boundaries the free arrangement and progressive restudy of the land use and traffic-flow diagrams as long as the established caps are rebalanced and not exceeded and as long as the plan remains consistent with community goals.

Consider the transfer of development rights (TDR). In recognition of the fact that for reasons of their ecologic, scenic, or other values certain areas of land and water should be preserved in their natural state, TDR provisions allow and encourage a developer to transfer from the sensitive area those uses originally permitted by zoning. Although the relocation of the uses or dwelling units to another property is sometimes provided, TDR is most effective when the densities of contiguous building sites in the same ownership are increased to absorb the relocated units.

Relate all studies to water resource management. The fourfold purpose is to prevent flooding, protect water quality, replenish freshwater reserves, and provide for wastewater disposal.

Provide perimeter buffering. As supplementary or alternative open space, a band of land in its natural state may well be left around the borders of larger development sites. This provides a screen against adjacent trafficways or other abutting uses and offers a welcome backdrop for building construction.

Create a community portal. One of the best ways in which to engender a sense of neighborhood or community is by the provision of a cohesive circulation system and an attractive gateway.

Ensure regional access. Thriving communities need connection to the shopping, cultural, and recreation centers and the open spaces of the regions which surround them. Aside from paths and controlled-access roadways, linkage may be attained by bikeways, by boat if on water, and by rapid transit in one or more of its many forms.

Preclude through-community trucking. Although local streets must be used on occasion by heavy trucks (by permit) and for daily deliveries by smaller vehicles, a direct truckway link to the community storage and distribution center has many advantages. Here heavy loads may be broken down for home or commercial delivery and bulk and private storage space provided for seasonal equipment, boats, and recreation vehicles.

Plan an open-space framework. As an alternative to facing homes and other development directly upon trafficways, many communities now wisely provide for the reservation of variformed swaths of land, in public or private ownership, as preferred building frontage. Vehicular approach to buildings, parking, and service areas is from the rear. The open-space system, which usually follows streams and drainageways, may also include walks, bicycle and jogging paths, and wider recreation areas.

Home-to-home relationships across a busy street or highway …

should give way to roadside clusters around a shared court.

Plan a hierarchy of trafficways. Even in smaller communities a clear differentiation between arterial, circulation, and local-frontage streets ensures more efficient traffic movement and safer, more agreeable living areas.

Limit roadside frontage. Insofar as possible, the facing of buildings upon arterials and circulation streets is to be precluded, with intersections to local frontage streets spaced no closer than 660 feet.

Make use of three-way (T) street intersections. They reduce through traffic, increase visibility, and make pedestrian crossing much safer.

Provide for rapid transit. Sheltered bus and minitransit stops and attractive community rapid transit stations, where appropriate, do much to stimulate transit use and reduce vehicular traffic.

Integrate paths of movement. Only when streets, walkways, bicycle trails, and other routes of movement are planned together can their full possibilities and optimum interrelationships be realized.

Vary the housing types. A well-balanced community provides not only a variety of dwellings, from single-family to multifamily, but also accommodates residents of differing lifestyles and a broad income range.

Vary housing type. © D. A. Horchner/Design Workshop

Include convenience shopping. © D. A. Horchner/Design Workshop

Encourage community programs. Nelson Byrd Woltz Landscape Architects

Systematize the site installations. All physical elements of a community—buildings, roadways, walks, utilities, signage, and lighting—are best planned as interrelated systems.

Cluster the buildings. The more compact grouping of individual dwellings and the inclusion of patio and zero-lot-line homes yield welcome additional open space for neighborhood buffering and recreation use.

Feature the school-park campus. The combining of schools with neighborhood and community parks permits much fuller use of each at substantial savings.

In Great Britain a charitable organization called the Learning Through Landscapes Trust has transformed nearly 10,000 school yards into imaginative learning gardens.

Landscape Architecture magazine, October 1994

Include convenience shopping. While regional shopping centers fill the largest share of family marketing needs, they usually require travel by automobile. Neighborhood and community centers, with access by walks and bikeways, are needed to provide for a lesser scale of convenience shopping and service.

Provide employment opportunities. Bedroom communities—those planned for residential living only—require the expenditure of time, income, and energy just to get to and from work. Integral or closely related employment centers add vitality and convenience.

Relate to the regional centers. The larger business office campus, industrial park, or regional commercial mall is best kept outside, but convenient to, the residential groupings. Such centers are logically located near the regional freeway interchanges and accessible to the interconnecting circulation roads.

Plan for transient accommodations. When highway-related motel, hotel, or boatel accommodations do not otherwise fulfill the traveler’s needs, a community inn is a welcome addition.

Consider a conference center. In addition to the auditorium and meeting rooms of the school-park community centers, a conference facility related to the commercial mall, business office park, cultural core, marina, golf course, tennis club, or inn is a popular amenity and asset.

Make recreation a way of life. Aside from private recreation opportunities and those provided at the neighborhood and community school parks, there is usually need for swimming, golf, and racquet clubs, a marina and beach club if the community is on water, a youth center, and access to hiking, jogging, and bicycle trails. The broader the range of available recreation, the more fulfilling is community life.

Encourage community programs, activities, and events. Although many do not require special space or site areas, no development program could be complete without consideration of all those social activities that contribute so much to community living. These include worship, continuing education and health care programs, children’s day care, a craft center and workshop, a little theater, game and meeting rooms, a newspaper, service clubs, Little League, dances, contests, and parades. Some start spontaneously; others may require encouragement and guidance.

Build out as you go. Scattered or partially finished building areas are uneconomical and disruptive. In the better communities, construction proceeds by the phased extension of trafficways, utilities, and development areas. They are completed as examples. Construction materials and equipment are brought in from the rear, and the prearranged staging areas and access roads retreat as the work advances.

Honor historic landmarks. Barry W. Starke, EDA

Establish nature preserves. Christopher Brown, FASLA, JJR|Floor

Ensure a high level of maintenance. A maintenance center and enclosed yard, perhaps combined with a water storage or treatment plant, is best located inconspicuously at the periphery, with ready access to trucking and the areas to be served. It is to be well equipped and phased in advance of development to provide complete maintenance from the very start.

Honor the historic landmarks. When features of archaeological or historical significance exist, they are to be cherished. Their presence extends knowledge of the locality, its beginnings, and traditions and gives depth of meaning to life within the community.

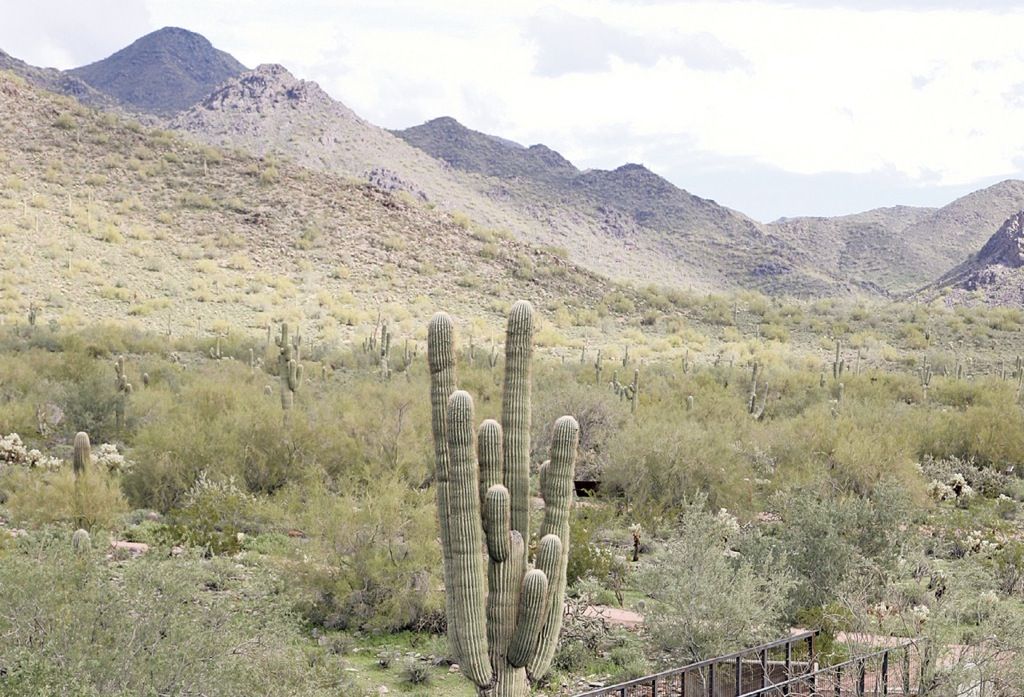

Establish nature preserves. Every locality or site has in some degree its prized natural features. Be they subtle or dramatic, they add richness and interest and are to be protected, interpreted, and admired.

Name a scientist advisory council. In both initial and ongoing planning much can be gained by the naming of a team of scientist advisers. Convened periodically to bring their expertise to bear on the evolving plans and proposals, they are especially helpful in the study of large, complex, or ecologically sensitive holdings.

Appoint an environmental control officer. In the phased construction of each new parcel the responsibility for environmental protection is best centralized in one trained person who is present during all phases of planning, design review, and field installation.

Form a design review board. The plans for all buildings and major site improvements are best subjected from the start to a panel of qualified designers for review and recommendation as to acceptance, rejection, or modification. An architect, a landscape architect, and the environmental control officer would be appropriate members.

Prepare a development guideline manual. As the basic reference document for all planning, design, and continuing operation of the community, an expanding loose-leaf manual is essential. As it evolves, it will contain:

- The community goals and objectives

- The conceptual community plan

- Each phased neighborhood or parcel plan as it is brought into detailed study

- A section and flowchart describing plan review procedures

- Plan submission requirements and forms

- Architectural design guidelines

- Site design guidelines

- The master planting plan and policy and recommended plant lists

- A section on environmental quality control

- A section on energy conservation

- A section on solid waste disposal and recycling

- Homeowners’ association covenants

As the need arises or is foreseen, supplementary sections will be added and the manual kept updated and complete. To be fully effective, its provisions must be equitably and uniformly enforced.

Establish a means of governance. It is important from the start of planning to have in mind the type of political entity that the community is to be or to become a part of. This will be a key factor in the determination of the type and level of public services to be provided and of responsibilities for planning reviews and permitting, for the installation of utilities, streets, and other improvements, and for taxation and decision making.

Create a homeowners’ association. The developer, builders, and final homeowners all benefit by the early formation of a permanent organization in which the owner of each lot or home has a pro rata responsibility and vote and to which assessments are paid. The purpose of the association is to provide the mechanism for the formulation and implementation of continuing community maintenance and improvement policies.

Ensure flexibility with control. The most successful American communities have been guided in their development by policies that accomplish the following:

- Establish the broad outlines of compatible land use and routes of movement

- Provide the guidelines required to ensure flexibility, design quality, and environmental protection

- Encourage individuality and creativity

Unmanaged growth is a cancer on the land. Barry W. Starke, EDA

In the coming decades one of the most important aspects of land planning will be that of growth management. On the face of it, the regulation of population expansion and distribution might seem an impossibility. How, for instance, can the awesome burgeoning of our population be brought under control? Yet this is imperative, for by present projection it will double and then double again within the next 100 years. One can imagine the stress on buildable land, farmsteads, food production, freshwater reserves, and roadway capacities.

Or how can the constant shifting or tidal flows of population migration within our borders be managed? These vexing and critical problems are at last being addressed by our institutions and government. Pending effective solutions nationally, there are many means by which our planning professions can improve the local situations and prospects.

The Guideline Plan

To manage growth and ensure sound development within a given locality it is essential that each community, city, and/or region have a clear understanding of existing conditions and what they might better be in the future.

Growth management is a search for the best relationships of people to land, water, other resources, and to routes of travel.

This implies the need for a planning committee, council, or commission, depending upon the size of the area concerned. Ideally such groups represent the best of the local leadership aided by a professional planner and staff. Their task is the preparation of a guideline plan and action program. This will define the types, locations, and limits of development foreseen to produce the most desirable conditions for living and working. It will preserve and protect the best of the natural features including forest and farmland. It will provide a protective framework of open-space lands, around which development is to occur. It will allocate areas for all types of uses deemed necessary to produce in time a balanced and stable community. It will provide for interconnection of the various activity centers with a system of free-flowing paths, streets, parkways, and freeways. It will be general in outline with flexibility to meet changing conditions.

This guideline plan and improvement program is to be constantly updated and revised for use in reviewing all future development proposals.

Project Review

Wherever uncontrolled development is permitted, it will in time occur—most often causing an unwelcome incursion. Road and utility capacities are exceeded, natural features destroyed, farmland eliminated, and school systems overloaded. Pleasant communities are disrupted and changed beyond redemption. Often their very nature is so changed that existing homeowners move to more agreeable surroundings.

How is such disruption to be prevented? It is easier than might be supposed. Where a planning committee or council exists and where a development plan and guideline program have been prepared, each new development project must meet the test of phased review to meet approval or be rejected.

The first phase is a determination that the proposed project meets the spirit and conditions of the guideline or can be amended to do so. If tentative approval is granted, the development is carried through a series of further stages, which include a detailed impact statement, cost/yield analysis, and posting of performance bonds if called for. Only with such a strict review process and presentations in public meetings can the citizens and their leadership be assured of orderly growth and transition.

Required Services

Having satisfied the suitability and project review phases, the final key to growth management is the assurance that all public services are in place and operation before the first occupancy is permitted. Such services include required approach-road improvements, all off-site utility leads, adequate fire and police protection, school facilities (in the case of residential development), open space, and recreation. Who pays for their provision? It only makes sense that the speculator/developers—not the existing citizens—pay for the costs involved.

Even well-planned development is not always good—especially when it throws established systems out of kilter. Uncontrolled development is seldom desirable because of its disruptions and costs to the members of the existing community. Unmanaged growth results in that cancerous American form of land use and development known as urban sprawl.

Much of what needs to be done in the way of environmental planning falls within the category of growth management. This goes beyond the obvious need to stabilize the doubling, redoubling, overwhelming, and shifting populations. It deals essentially with bringing people, land, and other resources into balance. In this endeavor it can directly affect the future of every region.

There are some—yea, many—localities where a desirable equilibrium has already been attained; where land is preserved or built out to capacity in its “highest and best use”; where trafficways, utilities, schools, and other amenities are working well together and where further growth would be disruptive. Again, there are areas of scenic splendor, ecologic sensitivity, or high agricultural productivity where the existing condition is best left largely undisturbed. In every region, however, there can be found potential sites for well-planned communities or other enterprises if and when it can be established that they belong.

Unless or until our exploding population growth is checked, more and ever more construction is inevitable. We can no longer, however, allow the uncontrolled development of our prime remaining natural or agricultural lands. We must first explore and maximize the possibilities of renewal and redevelopment. We must reclaim, redefine, reuse, and often reshape our obsolescent or depleted urban, suburban, and rural properties. We can and must create a whole new re-formed landscape within the grand topographical setting of protected mountain slopes, river basins, shores, desert, forest, and farmland.

Implicit in long-range planning is the concept of sustainable development. For unless continuity is planned into the system, the term “long-range” has little meaning. Ideally, the supply of land, water, and other resources would be inexhaustible. Since this is not a fact of life, our planning must be the formulation of strategies for restraint, wise use, replenishment, and restoration.

It involves such broad and diverse concerns as the efficient use of energy. It deals with such finite matters as limitation on consumption, land use controls, and recycling. As to land and landscape planning, it soon leads to the realization that urban sprawl and scatteration must be curbed and reversed—replaced with concentrated and interconnected centers of human activity within protected and productive open-space surrounds. It demands, in short, comprehensive regional planning.

Golden Gate National Recreation Area. Tom Fox, SWA Group

In our planning and replanning, we must preserve intact such significant natural areas as are necessary to protect our watersheds and maintain our water table, to conserve our forests and mineral reserves, to check erosion, to stabilize and ameliorate our climate, to provide sufficient areas for recreation and for wildlife sanctuary, and to protect sites of notable scenic, ecologic, or historic value. Such holdings might best be purchased and administered by the appropriate federal, state, or local agencies or conservancy groups.

We must ensure the logical development of the existing landscape. Such thinking points to a national resource planning authority. Such an authority would be empowered to explore and determine, on a broad scale, the best conceivable use of all major land and water areas and natural resources. It would recommend the purchase of those that should be so conserved. It would encourage, through zoning, enabling legislation, and federal aid, the best and proper development of these and all remaining areas for the long-range good of the nation. It would constantly reassess and keep flexible its program and master plans and engage for this work the best of the trained physical planners, geographers, geologists, biologists, sociologists, and experts in other related disciplines. Regional, state, and federal environmental advisory boards composed of distinguished scientists and thinkers might well be constituted, with participants nominated to this post of high honor by their respective professional groups.

Further, we must consciously and astutely continue the evolution toward a new system of physical order. This may be one of improved relationships, as of people to people, people to their communities, and all to the living landscape. Since we have now become, in fact, world citizens, the new order may stem from a philosophic orientation that borrows from and incorporates the most positive driving forces of the preceding and contemporary cultures.

While the Athenians, as has been noted, faced their homes inward to family domains of privacy, while the Egyptians expressed a compulsion for lineal progressions, while the Chinese designed their homes and streets and temples as incidents in nature, and while the Western predilection was for a continuum of flowing space, perhaps the new universal philosophic guidelines may be a felicitous blending.

The value of the secure, private contemplative space may come to be generally recognized. The appreciation of lineal attainment may be translated into the design for pleasurable and rewarding movement along transitways, parkways, and paths. Whole cities and regions may be harmoniously integrated with natural landscape, in which interconnecting open space may provide a salubrious setting for our new architectural and engineering structures.

For the first time in the long sweep of history, environmental protection is becoming at last a world concern. The wise management of our land and water resources and the earthscape is becoming a common cause. Fortunately, when the problems are nearing crisis proportions, the essential technology is at hand. Perhaps we can pull it all together in time, and sooner than many suppose, with enlightened, creative planning.

Small urban improvements. W Architecture and Landscape Architecture. www.w-architecture.com; Barry W. Starke, EDA; David Vadlowski/City of Vancouver

Significant environmental improvement does not necessarily require a monumental effort. It is sometimes achieved at a massive scale, as by effective and far-reaching flood control programs, clean air legislation, or the scientific management of regional farmlands, wetlands, or forest. For the most part, however, it is accomplished on a far lesser basis. It is the sum of an infinite number of smaller acts of landscape care and improvement. It is:

- The advent of a well-designed park or parklet

- The placing underground of power distribution and telephone cables in a new community

- The cleanup and water-edge installation of paths and planting along a forgotten stream

- Neighbors caring for their street

- A linden tree installed beside the entrance of an urban shop

- A vine on a factory wall

- A scrap of blowing paper picked up by a child in the school yard

Each act generates others. Together, they make the difference.

It is believed that there is no greater threat to our cities and outlying countryside than the blight of urban sprawl. The subject is given place in this text because most readers with such an interest are those best suited by training and experience to deal with and solve this problem.

Rampant sprawl followed World War II. Tom Lamb, Lamb Studio

The early towns and cities of America were compact and self-contained. Compact for convenience. Streets were muddy. Horses, the only means of locomotion, had to be harnessed and hitched to buggy or wagon. The hostile forest closed in around. Self-contained because the only goods and foodstuffs available were to be gathered from the forest or garden or bought at the general store.

When towns and cities grew by accretion, their centers were strengthened by the growth that crowded around them. As new roads and highways were built, comparable settlements formed as nodes along the way, soon to be surrounded by farmsteads. When the railroads came, new settlements coagulated at railroad or river crossings or natural harbors. In time, transportation routes also found their way to remote centers of agriculture, mining, lumbering, or to notable scenic attractions.

Growth management is not a door slamming shut, as some might think—as some might wish. It is more of a regulating valve by which flow and capacities are brought into optimum balance.

This congenial land use pattern prevailed until after the Second World War. Then, with rampant industrialization and the rapid extension of our road and highway networks, the urban centers, with their frictions and fumes, had less appeal and the open countryside beckoned. Existing homeowners or builders moved out from the towns and cities to outlying homesites or the evolving suburbs, which were an American invention. Stores and factories followed—to leave the hemorrhaging cities with ever-increasing vacancies, dilapidation, and taxes. An influx of lower-income families and welfare recipients exacerbated the problems.

Not only the cities were faced with the resulting dilemmas—for wherever new development occurred in the rural landscape, the adjacent farm- and forestlands were taxed, not according to their use, but as potential development acreage. A swelling tide of farmers were tempted, or forced, to sell their farmsteads and add to the scatteration.

Pittsburgh Point, circa 1990. Historical Society of Pennsylvania Archives

And so we find ourselves today. Almost without exception our towns and cities are burdened with debt, pocked with obsolete or vacant structures, woefully polluted and crime-ridden. In the surrounding outlands, thriving family-owned farms are becoming a rarity. The once unspoiled “America the Beautiful” is cluttered with a maze of poorly maintained roadways and unplanned scatteration. In time, the owners of outlying dwellings demand paved access, utilities, and such public services as schooling and busing. It is hard to imagine a less efficient or more destructive pattern of development. It has come to be known, and vilified, as urban sprawl.

Fortunately, there are today those with a compelling vision of a better way—and the knowledge by which troubled neighborhoods and cities can be restored to health and more rational cities and metropolitan regions planned into being. Each of the antidotes which follow describes a tried and proven approach to land use planning that has produced an environment for living that is more comfortable, convenient, efficient, and fulfilling.

Individually or in sum they point the way to the end of urban sprawl and the comprehensive planning of far more desirable living and working centers.

Urban revitalization is a major weapon against sprawl. Kongjian Yu/Turenscape

The City

Urban sprawl is for the most part flight from the city. When a city is grossly polluted, poorly maintained, crime-ridden, and heavily in debt; when the beckoning countryside is largely unzoned; and when a network of unrestricted roads leads outward—this exodus is understandable.

What would it take to stop the outflow and reverse the trend—to bring the entrepreneurs and home builders back? One answer, of course, is to renovate the city and make it safer and more attractive. In city after city this has proven to be not only feasible but an accomplished fact.

Activity Centers

Activity nodes—such as those of communities or commercial, business, research, medical, university, or recreational centers—are working entities. They can be unplanned and awkward, or they can be designed or redesigned to function like a well-tuned machine.

To better things for any type of center, it is well to list those components necessary to make it complete—including housing for the workers—and then designate areas for them to be constructed phase by phase for optimum performance.

Each activity node is to be connected to others and the center city by parkway or rapid transit. Such complete and functional centers planned within the cities, or (if needed) beside controlled access highways, provide a highly desirable alternative to urban sprawl. In addition, they greatly reduce place-to-place travel time and traffic. They are more pleasant and convenient. They are more profitable and successful for all concerned.

Fixed Boundaries

Scatteration or urban sprawl is the creeping dispersion of the more successful enterprises and more desirable housing into the surrounding countryside. All sorts of support services follow along. Not only does this weaken vital centers, it infiltrates the outlying agricultural, forest, and wetlands with a network of incompatible roadways and ill-matched types of development.

How can this hemorrhaging of the city and the disruption of the surrounding region be precluded? Only by the imposition of fixed boundaries and development controls to check the outward pressures.

Where strong metropolitan or regional planning commissions are in place, such confining limits can be accomplished by strictly enforced zoning. There will be opposition by speculators, but the benefits of the confined cities and centers are overwhelming. With land area at a premium, vacant lots and obsolescence are rare; maintenance, land values, and tax yields are high and the economy thrives. Moreover, the center is complete, convenient, and in balance.

Open Space

What constitutes open space? It is unpaved, un-built-upon land or water bodies. Within a metropolitan area, the best possible open-space system is comprised of recreational parks or parklets aligned along the natural streams and drainageways. The latter, preserved to the 50-year flood level, form an interconnected swath of green where the soils are richest and the foliage and tree cover most luxuriant. Here, within or beside the swath, is the preferred route for parkways, bikeways, and walking/jogging paths. They belong in the public domain. Even where presently enclosed in concrete culverts or built upon, waterways can in time be reopened and restored to their natural flows. Urban open space can also be provided by planted parkway medians and berms, by institutional grounds and in-city forests. Street trees supplement open space by serving as windbreaks in the trafficway channels and by providing welcome shade and cooling.

Open space comes in countless forms. © D. A. Horchner/Design Workshop; Tom Fox, SWA Group; OLIN; © D. A. Horchner/Design Workshop; Cole, USDA; EPD

The urban pattern of the future will be one of compact and confined centers surrounded by park and recreation lands, gardens, agricultural fields, nature preserves, or forest. Internally and externally, nature will always be close at hand, with urban sprawl precluded.

Roadways

Presumably, highways are designed to move motorists safely, efficiently, and pleasantly from place to place. Yet, except for national parkways, turnpikes, and interstate highways, there are few trafficways without buildings fronting upon them, together with driveway openings—sometimes 100 or more per mile. Every car slowing down to turn off or to allow another to enter reduces the capacity of the highway and flow of traffic—often to a standstill. By what right are abutting property owners permitted to convert highways built with public funds into highly valuable private building frontage? Highway engineers know the hazard and friction of roadside intrusion and would opt for development-free borders along all major roadways. By all reason, new through highways and arterials should be designed with limited access—with off- and on-ramps no closer than one-quarter mile on each side. Privileged landowners would no longer gain at others’ expense; the traveling public would have the free-flowing highways they paid for and deserve. Thus, too, could be eliminated mile after mile of sordid strip commercial and unplanned sprawl.

Land Value Appreciation

Developers are often blamed for our woes. Sometimes rightly so. But in fact, the better developers are a key to salvation. Given an enlightened governmental and planning framework that encourages sound and creative development, the large-scale, long-range landowner developer is the hope of the American landscape.

Two key provisos of growth management policy are that entrepreneurs contribute their fair share of the funds needed for off-site improvements and that all required services be in place before occupancy is permitted.

Alone, or in a consortium, only the heavyweight developer has the financial depth and staying power to:

- Assemble sizable tracts of buildable property

- Produce a community or other activity center in accordance with a comprehensive plan that addresses all pertinent considerations and includes all needed components

- Build in phases, toward long-term completion

- Reserve and dedicate large stretches of the most scenic, sensitive, or productive open-space land

- Engage experienced planners and top scientific advisers

- Coordinate fully with such public agencies as the transportation authority, school district, water resource management district, park/ recreation/open-space board, and regional planning authority

The large-scale, long-range developers have a reputation to gain and protect. Proven, high-quality performance makes everything easier. With a very significant investment at stake, they well know that any blighting uses or construction would be harmful to their reputation and relationships—and also to their investment. The goal of all experienced landowners or developers is land value appreciation. In simplest terms this means that everything built or changed adds value to the remaining land.

Recentering

Almost without exception, the dispersed elements of uncontrolled sprawl cause stress and disruption. The problem is not only that of disturbing the intruded land but mainly that of connecting those elements to shopping, schools, and other destinations—all at public expense.

Where in time their location is found to be unfavorable—as by reason of climate, topography, lack of conveniences, friends, or employment—they are usually sold for lesser uses or abandoned as a total loss. Many of the isolated homesteaders or owners of other enterprises soon miss the advantages of planned communities or the renovated city and opt to return or move on.

What can be done to heal scatteration and restore the integrity of rural lands? There are many possibilities. Among them:

- The scattered parcels can be assessed and taxed to cover the cost of the required services and off-site improvements. This, in most cases, would soon make remote living prohibitive.

- Acquisition by purchase of an unsuitable property is the direct approach. Often it costs less for a jurisdiction to buy the home or development than to provide the road improvements, maintenance, and schooling. A condition of purchase can be the granting of lifetime tenancy for the owners.

When the perceived advantages of dispersed living are outweighed by those of new or replanned centers, the owners will gravitate to the more attractive locations. The gradual regrouping of the scattered elements into well-defined and balanced activity centers—each with its supporting services and adjacent worker housing—creates a much more desirable environment for living the good, full life.

Zoning

Conventional zoning as it is commonly practiced is as harmful as it is archaic. In traditional zoning practice, large areas of land are set aside and restricted to a single type of use, as for detached single-family homes, row houses, or apartments, or, again, as for commercial development, business office, light or heavy industry, institutional, recreational, or open space. The zoned areas are often delineated without thought of topography, the transportation network, or even abutting land uses. Usually they are oversized “to be sure of sufficiency,” and in response to political pressure by landowners who buck for the highest potential sales value of their property. Such overzoning results in large un-built-upon tracts within the metropolitan area—increasing the costs of interconnection by road and utilities and encouraging, rather than discouraging, scatteration even within the city.

Zoning cannot be a substitute for planning, and planning cannot be a substitute for design—the three must work together.

An advanced, and highly successful, form of zoning is that of planned unit development (PUD), which is especially designed for complete and balanced community or activity center planning. In each case, for a given parcel or tract, existing zoning restrictions are relaxed and creativity is encouraged. Homes and other buildings may be arranged freely. They need not face upon a public street. They may instead front upon off-street courts, plazas, or dedicated walkways—with parking bays or compounds located beside or underneath. They may be designed with a mix of low to high-rise buildings and with such supporting uses and services as may be needed to make the community or center complete.

Such PUD-designed activity centers are in all ways superior to the traditional pattern of structures lined out along streets and highways, with their danger, fumes, and noise, and without ready access to recreation, schools, or convenience shopping. With such attractive in-city communities and educational, commercial, or other centers as can be produced under PUD zoning procedures, there is far less incentive to flee the city and follow the highways to somewhere out beyond.

Construction Regulations. One of the common inducements to urban sprawl is the lack of siting and building regulations in the outlying districts. While some may have zoning and building codes, they are usually loosely enforced, if at all. This invites an invasion of those who seek a place in the woods or beside a stream or along some country farm road, where they may clear and grade out a level spot and build a cabin, shack, or house, or haul in and hook up a trailer. It is to be noted that throughout the countryside there are many attractive mobile home parks that show the multiple advantages of grouping isolated units into thriving communities. Even the most modest rural intrusion causes disruption, but when extensive clearing and grading is involved the result may be a neighborhood disaster. In less than one day, the gung-ho operator of a bulldozer or chain saw can trash a whole hillside and subject it to ever-deepening erosion—or cause miles of stream pollution and siltation in the drainageway below.

The frontiers of waste management are yet to be explored. Beyond the exclusion of trash landfill mountains and offshore refuse reefs are the possibilities of massive topsoil replenishment. A blend of salvaged wood fiber, pulverized plastic, and glass mixed with processed sewage could in time restore to vast areas of eroded land a productive soil mantle.

A positive planning approach. Beach and wetlands are preserved; residential clusters, from single-family neighborhoods to towers, are confined to the uplands; there is raised beach access for all. WCI Communities

Needed is a mandatory statewide land use and construction code that is strictly enforced. The provisions will vary with the geographic location—as for coast, prairie or plain, mountains, river basins, or wetlands. In each case, however, the following subjects should be among those addressed:

- Land use

- Impact statement

- Slope protection

- Clearing of natural vegetation

- Earthwork (excavation, filling, and grading)

- Topsoil conservation

- Drainage of wetlands

- Blocking of natural drainageways

- Water supply

- Road frontage

Without such regulation, the blight of sprawl is bound to spread. With enforced legal controls, urban sprawl can be stopped and its ravages healed.