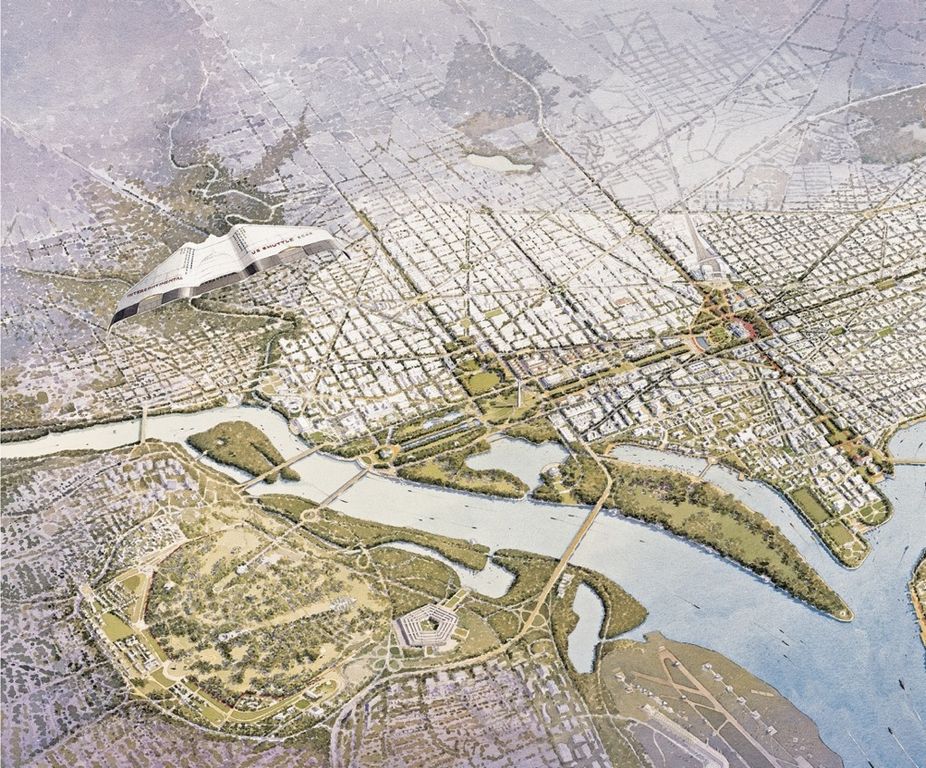

Illustration courtesy of the National Capital Planning Commission’s Extending the Legacy Plan. Rendering by Michael McCann.

It sometimes seems that our contemporary planning is an unholy game of piling as much structure or as much city as possible in one spot. The urban areas to which we point with pride are often merely the highest, widest, and densest piles of brick, stone, and mortar. Where, in these heaps and stacks of masonry, are the forgotten, stifled people? Are they refreshed, inspired, and stimulated by their urban environment? Hardly, for in our times, too often a city is a desert.

To be bluntly truthful, our burgeoning American cities, squared off and cut into uncompromising geometric blocks by unrelieved, unterminated trafficways, have had more of this arid desert quality than those of other cultures past or present.

If we compare a map of Rome as it was in 1748 with a recent aerial photograph of New York, we marvel at the infinite variety of pleasant spaces that occurred throughout the Eternal City. Of course, as Rasmussen has pointed out in Towns and Buildings, “Great artists formed the city, and the inhabitants, themselves, were artists enough to know how to live in it.” We wonder why such spaces are for the most part missing in our contemporary city plans.

Traditionally, the urban spaces of America have been mainly corridors. Our streets, boulevards, and sidewalks have led past or through to something or somewhere beyond. Our cities, our suburbs, and our homesites are laced and interlaced with these corridors, and we often seek in vain to find those places or spaces that attract and hold us and satisfy. We do not like to live in corridors; we like to live in rooms. The cities of history are full of such rooms, planned and furnished with as much concern as were the surrounding structures. If we would have such appealing outdoor places, we must plan our corridors not as channels trying to be places as well but as free-flowing channelized trafficways. And we must plan our places for the use and enjoyment of people.

Our contemporary landscapes are characterized by immense metropolitan airports, zig-zag patterns of high-voltage power lines and disturbed historical sites. Our familiar landscapes are not small farmsteads and dirt roads, rather they are the yawning expanses of urban development.

Patricia C. Phillips

The City Experienced

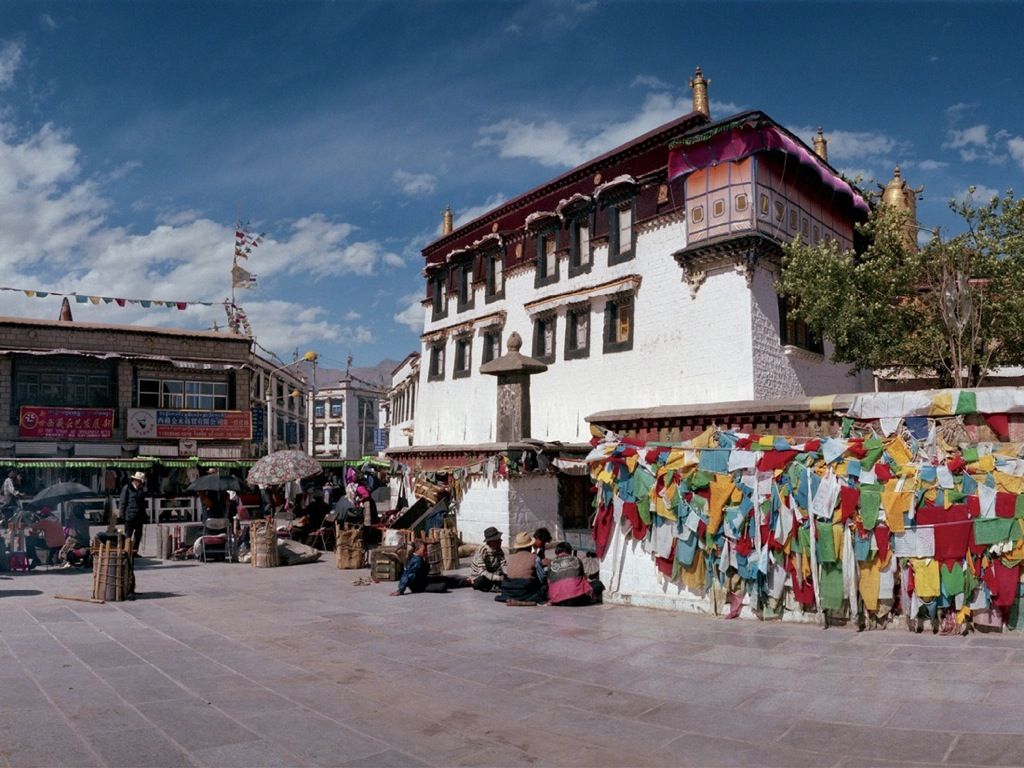

The old cities of Europe, Latin America, and Asia had, and still have, to their credit and memorable charm, their plazas, piazzas, courts, squares, and fountains and their distinctive, indefinable, uplifting spirit of joie de vivre. These cities were conceived as three-dimensional civic art and in terms of meaningful patterns of form and open spaces. Our cities, with few exceptions, are oriented to our traffic-glutted streets.

According to a recent poll, most Americans (56 percent), if given the choice, would now prefer a rural life; 25 percent would opt for the suburbs, and only 19 percent for an urban living environment.

Whom are we to blame for this? Aristotle, in his Rhetoric, states, “Truth and justice are by their nature better than their opposites, and therefore if decisions are made wrongly, it must be the speakers who (through lack of effective powers of persuasion) are to blame for the defeat.” For our purpose, this passage might well be paraphrased: “Facility, interest, and beauty are by nature better than chaos, the dull, and the ugly, and therefore if decisions are made wrongly, it must be we planners who, through lack of effective powers of persuasion (or more compelling concepts of urban living), are to blame.”

Large cities seen from an altitude of several hundred feet do not present, as a whole, an orderly facade. Their vastness is their most striking feature; whatever quality they possess is lost in sheer quantity. Areas that give evidence of planning occupy but a small surface. Disorder predominates. Buildings are piled up near the center and scattered haphazardly towards the outskirts. The few green spots and other places of beauty known to the tourist, seem hidden in a maze of grey and shapeless masses that stretch toward the surrounding country in tentacular form. The very borders of the city are undefined, junk and refuse belts merging with the countryside. If on beholding this sight we pause to contemplate modern cities and consider what they could have been if planned, we must admit in the end that, in spite of their magnificent vitality, they represent one of man’s greatest failures.

José Luis Sert

In searching for a more enlightened approach to urban planning we must look back and reappraise the old values. While recognizing the fallacies of the “city beautiful” in its narrowest sense, we must rediscover the age-old art of building cities that inspire, satisfy, and work. And surely we will, for we are disturbed by the vapid nature of the cities we have planned or, worse, have allowed to grow unplanned in sporadic, senseless confusion.

Evident Needs

We, in contemporary times, have lost the art of, and feeling for, overall plan organization. Our cities lack coherent relationships and plan continuity. With our automobiles as the symbol and most demanding planning factor of our times, we have found the meandering streets, places, and plan forms of the ancient cities to be unsuitable. We have rejected (with good reason) the synthesizing device of the inexorable “grand plan” but have found, for the most part, few substitutes save the mechanical grid and other patterns of uninspired geometry. The transit, the protractor, and the compass have delineated for us a wholly artificial pattern of living areas and spaces. We must and will develop new types of plan organization better suited to our way of life. In future urban planning considerations, the significant space is bound to return, and we will again have ways and places as important as the structures.

The essential thing of both room and square is the quality of enclosed space.

Camillo Sitte

The basic tenet of urban design is disarmingly simple: the best city is that which provides the best experience of living.

From Giovanni Battista Nolli’s map of Rome. Map of Rome by Nolli, 1784, from Towns and Buildings by Steen Rasmussen

For the most part, it is proposed that those cities have proven most agreeable that are the most expressive of and responsive to their time, place, and culture; that are functional; that afford convenience; and that are rational and complete.

The corridor canyons that are New York City’s streets stretch on interminably without relief, without focal point, and without the welcome interruption of useful or meaningful space. Fairchild National, Inc.

The unit of measurement for space in urban society is the individual.…

Arthur B. Gallion

A city plan is the expression of the collective purpose of the people who live in it, or it is nothing.

Henry S. Churchill

The desert character of our cities is concentrated in the downtown core. Here the average cityscape is a conglomeration of metal, glass, and masonry cubes set on a dreary base plane of oil-splattered concrete and asphalt. It is bleak, chill, and gusty in wintertime, and in summer it shimmers and weaves with its stored-up, radiating heat. Within view of its naked towers, the open countryside beyond is often many degrees warmer in winter and cooler in the summertime.

The first step in adequate planning is to make a fresh canvass of human ideals and human purposes.

Lewis Mumford

From cradle to grave, this problem of running order through chaos, direction through space, discipline through freedom, unity through multiplicity, has always been, and must always be, the task of education, as it is the moral of religious philosophy, science, art, politics and economy.

Henry Adams

Such an oppressive and barren cityscape falls far short of the mark. Our cities must be opened up, refreshed, revitalized. Our straining traffic arteries must be realigned to bypass the city cores, to pass under or around the perimeter of unified pedestrian areas or levels in which offices, shops, and restaurants are planned together in close proximity and in which people may move about without on-grade crossings of trafficways. In contrast with the stark masonry canyons and roaring avenues, the new pedestrian domains will provide a garden-like setting for freely composed groupings of towers and terraced structures, variformed courts, and walkways—providing the welcome relief of foliage, shade, splashing water, flowers, and bright color. Like oases, such intensified multiuse plazas will transform the city into a refreshing environment for vibrant urban life. Many exemplary prototypes are appearing in America and abroad.

In thriving cities, each component district is well defined and fulfills its contributing functions.

Will the city reassert itself as a good place to live? It will not, unless there is a decided shift in the thinking of those who would remake it. The popular image of the city as it is now is bad enough—a place of decay, crime, of fouled streets, and of people who are poor or foreign or odd. But what is the image of the city of the future? In the plans for the huge redevelopment projects to come, we are being shown a new image of the city—and it is sterile and lifeless. Gone are the dirt and noise—and the variety and the excitement and the spirit. That it is an ideal makes it all the worse; these bleak new Utopias are not bleak because they have to be; they are the concrete manifestation—and how literally—of a deep and at times arrogant, misunderstanding of the function of the city.

William H. Whyte Jr.

To understand how a city works (or why it doesn’t work) and plan toward its improvement, it is helpful to dissect it into its various parts and to examine each part separately. Such an approach reveals the surprising fact that in few cities have such components been planned, or even considered, as functioning entities. As to components, for the purpose of this examination it is proposed that we consider, first separately and then together, the center city, the inner city, the outer city, and the suburbs.

The Center City, or Central Business District (CBD)

The center city serves a double purpose. It is not only the core of the urban metropolis, it is as well the polarizing and dynamic core of the whole surrounding region. Here one expects to find the centers of government, commerce, and trade; the principal financial institutions; and the corporate headquarters of industry, manufacturing, and communications. Here, too, are most often found the cultural superlatives—the cathedral, performing arts center, central library, museums, and galleries, and as well the theaters, stadium, and sports arenas.

There are, certainly, ample reasons for redoing downtown—falling retail sales, tax bases in jeopardy, stagnant real-estate values, impossible traffic and parking conditions, failing mass transit, encirclement by slums. But with no intent to minimize these serious matters, it is more to the point to consider what makes a city center magnetic, what can inject gaiety, the wonder, the cheerful hurly-burly that make people want to come into the city and to linger there. For magnetism is the crux of the problem. All downtown’s values are its by-products. To create in it an atmosphere of urbanity and exuberance is not a frivolous aim.

Jane Jacobs

Central Park, New York City, was the first public park built in America. A competition for its design was held in 1858; the winners, Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, were the first American landscape architects. This magnificent urban open space of 843 acres has attracted to its sides much of the prime residential, commercial, and cultural construction of the city. Its effect on real estate values, its inestimable contribution to the city, its ineffable meaning to all who see and sense and use it—these lessons should never be forgotten by the urban planner. Gerry Campbell, SWA Group

With each complex a small empire in itself, there is reason to allocate for each its own distinctive segment of the center. Since all segments share the need for shopping, dining, and hotels, a centralized superplaza is suggested, around which the various building groupings can take form. With few exceptions, parking, storage, distribution, and mechanical systems are to be relegated to subsurface plaza levels.

The central business district, in compression, will grow upward instead of out; obsolescence will disappear; densities will increase, and the core will regain its dynamic intensity.

Our present troubled, largely obsolescent, and woefully inefficient urban centers are spilling out over their boundaries and messing up their countryside. Such uncontrolled sprawl can and must be stopped. Not only for the good of the cities, which are losing their focal dominance and vitality, but as well for the farmlands, forests, and rural American landscape, which are rapidly going to pot.

An arcade or mall of shops and restaurants that never close helps keep the streets safe and the downtown vital. Occupants of upper-story apartments in office and commercial buildings add to the evening street life, and round-the-clock surveillance.

Within the CBD, through streets should be eliminated—phased out in time and replaced by circulation loop drives around and between the traffic-free plaza islands. These surface drives, bridged at the plaza-to-plaza crossings, will provide for the free circulation of cabs, buses, emergency vehicles, and a limited number of private cars by special permit.

The best way to promote security in a downtown area is to ensure that the streets are alive with responsible urban residents who come out to enjoy the evening sites and activities. In such an atmosphere, restaurants and theaters thrive, shops stay open, and people can linger or stroll about in relative safety.

On the linked plaza islands of the revitalized center will rise a new urban architecture. The freestanding megaliths of the present need to be replaced by interconnected complexes of high and low structures with flying terraces, roof gardens, inset patios, open courts, domed conservatories, and galleries. Aloft, boxed window ledges, balconies, and terraced setbacks will become the private gardens of the center city. Rooftop restaurants and illuminated recreation courts and pools will add sparkle and animation to the skyline. At pedestrian levels, buildings will open out upon a labyrinth of landscaped courts and meandering walkways. Passageways from place to place and level to level will be weather-protected. They will be flanked with seasonal exhibits, displays, and plantings—with flower stalls and book marts; candy, nut, and pizza shops; pretzel, fruit, and popcorn stands … and provision for sidewalk bazaars with paintings, carvings, crafts, antique jewelry, mechanical toys, entertainers, and all those divertissements that add excitement and pleasure to shopping.

The memorable cities of the world—London, Amsterdam, Paris, Copenhagen, Madrid, Athens, Rome, Montreal, New York, New Orleans, San Francisco—are those in which people live where they work. Civic and business centers are interspersed with town houses, apartments, and cafés, with bakeries and boutiques, with wine, cheese, fruit, and florist shops, and with artists’ studios.

Utilize rooftops. City of Vancouver

Revitalize existing open space. OLIN

Redevelop the waterfront. J. Brough Schamp

With surface traffic and parking restricted within the city center, rapid transit will flourish. (Such cities as Stockholm, Toronto, and Paris are telling examples.) Multilevel transit hubs, centrally located, are major regional destinations and points of transfer. Linked, computerized cars arrive and depart at swishing speeds through illuminated subsurface transitways or by aerial monorail.

Within a theoretical central business district (CBD), the circles represent major destinations such as banks, department stores, civic centers, regional sports facilities, or entertainment districts. The lines represent paths of pedestrian circulation. A closely knit set of CBD elements is mutually sustaining. A compact center makes for easy connections in terms of time, distance, and friction. Dispersion of the CBD negates the advantages of “downtown.”

It is proposed that the CBD of the future will be confined, and constricted, by a tight and inflexible ring to preclude its “leaking out” and ensure its intensity. Access by automobile via radial boulevards will be intercepted at the center-city perimeter by a decked distributor ring road within a spacious right-of-way. Vehicles arriving at the ring can either circumvent the CBD entirely if this is desired or enter by well-spaced ramps into the parking and transport levels of the plazas. The ring is more than a free-flowing trafficway. Its wide swath of space can accommodate ample open-air parking compounds as well as water management holding ponds and recreation areas. Here too, available to center-city visitors, can be located such attractions as elements of the zoo, botanic garden, and aviary. Or perhaps the annual art fair or ethnic festivals.

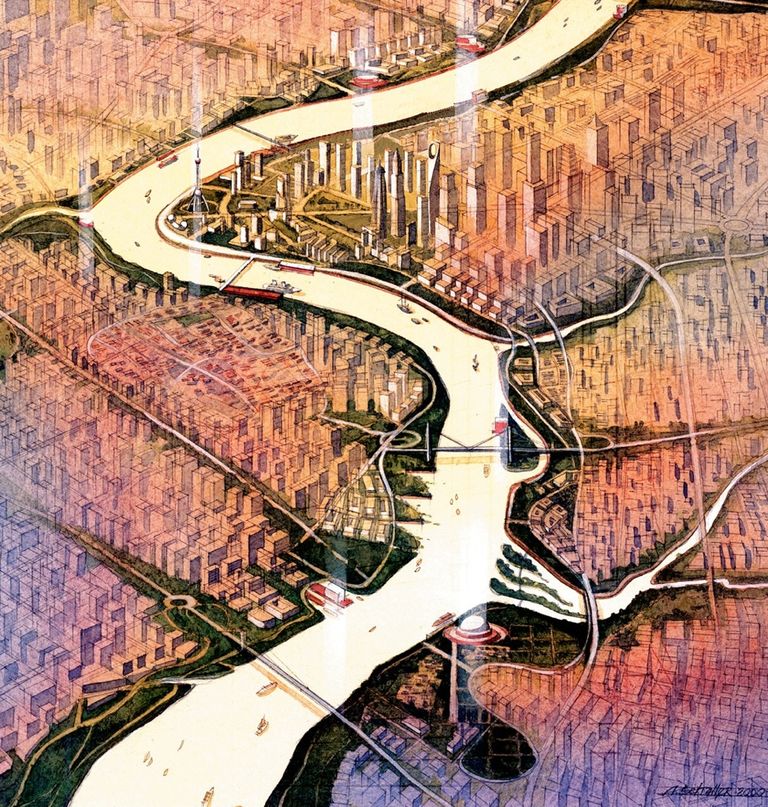

Planned CBD: Shanghai, Huangpu River. Sasaki Associates, Inc.

Patterns of mix are important. The vibrant centers are those in which the old is intermixed with the new, the low with the high, the simple with the elaborate.

When rows of shops and homes are interrupted by blocks of stark office towers or by blank building walls, evening street life is diminished. To sustain street appeal and nighttime activity, office and apartment towers are best grouped around off-street plazas or courts. Business, residential, and commercial relationships are all thereby intensified.

The layering of shops, apartments, and offices is proving to be a successful means of keeping the evening streets alive, with people at hand to enjoy them.

Housing? The more successful cities have proven the value of devoting the upper stories of buildings and towers to in-city apartments for executives and higher-salaried workers, who then in the evenings throng into the pedestrian ways and places to keep them alive and thriving.

The Inner City

Outward of the ring lies the area best described as the “inner city.” It is the band containing the bulk of housing and service facilities that provide the necessary support of the CBD and adjacent urban satellite communities. Commonly, in its present form, it is mostly obsolescent—left behind in the exodus of the previous residents who followed the expanding trafficways into the lands beyond. In its dilapidated state it is pocked with abandoned structures and vacant properties. Here and there are the remnants of once-thriving neighborhoods. Here too, one finds start-up businesses in reclaimed buildings and blocks of homes restored and renovated by enterprising newcomers.

Eminent domain is the authority by which a government or public agency can appropriate, with due recompense, private property for public use or benefit. To make the exercise of eminent domain more acceptable, its application may be conditioned by such provisions as:

- Use only after open negotiation has been tried and failed.

- Use only for the final 10 percent of the land required when a holdout has blocked acquisition.

- When long-range acquisition is in the public interest, grant the owner tenancy for a stated period of time.

- Purchase, with leaseback for conditional uses.

Available Opportunities

Here in the inner city, with its frequent stretches of boarded-up buildings and rubble-strewn land, there is opportunity to acquire at affordable cost the sites for clustered housing enclaves or whole new communities. Until recently this was not possible because of absentee or holdout parcel owners. Now, however, with innovative redevelopment techniques providing the powers of eminent domain, the sizable sites required can be assembled and cleared by a redevelopment authority.

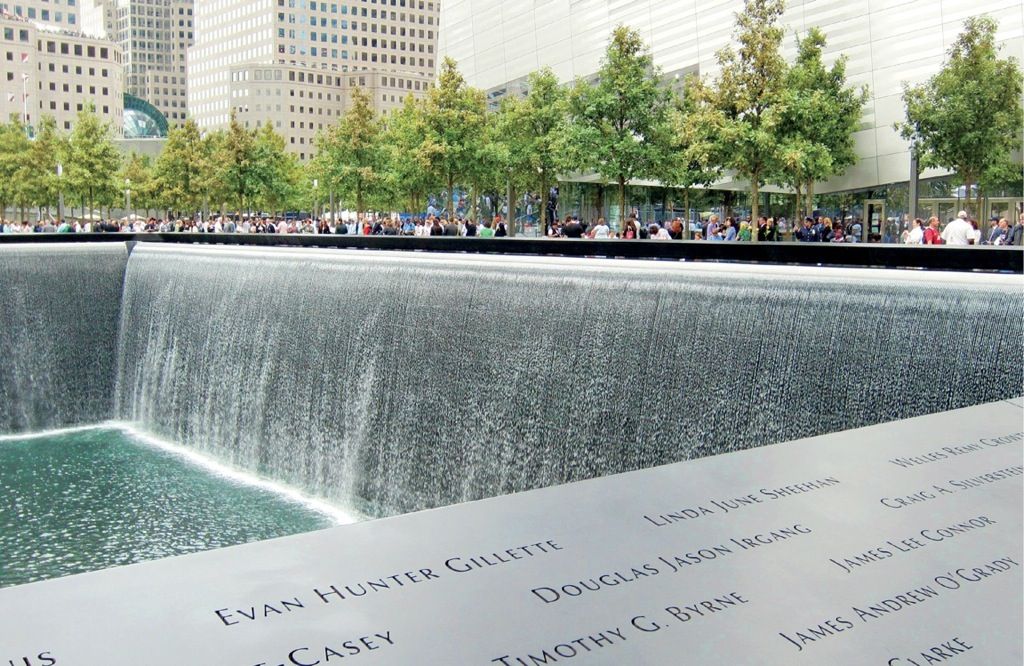

World Trade Center Memorial, New York City. PWP Landscape Architecture

In city after city, such reclaimed tracts of inner-city wasteland are now sprouting with well-planned, mixed-use, residential developments. Dwellings range in type from single-family homes to multistory apartments. Residents, many of whom are employed nearby, may be workers of low to moderate income or high-salaried executives.

The inner city offers the greatest opportunity for urban renewal and redevelopment, for with overall planning and self-help incentives it can provide not only the housing but also a wide spectrum of the service and supply facilities needed to support the adjacent CBD and the outer city. With unemployment and the lack of housing two of the major urban problems, the inner city teems with latent solutions.

Examples of inner-city housing. Jerry Howard/ Carol R. Johnson Associates; David Vadlowski/City of Vancouver; David Vadlowski/City of Vancouver; David Vadlowski/City of Vancouver; David Vadlowski/City of Vancouver

It is in the inner city that low- to moderate-income housing will make its most telling advances. While the tower apartments of the CBD (on costly land and with elevators required) will be designed mainly for residents with the higher incomes, the mixed-use neighborhoods outside the ring will include the full range of housing types for those of all income levels, including the displaced and presently homeless.

There is a truism to the effect that in every problem and seeming disaster are to be found the seeds of opportunity. In many ways our present cities are little short of disasters. Where then do the opportunities lie?

The inner city, where the problems seem most hopeless, may become the promised land. In this deteriorated band are to be found many sound homes and start-up business structures inviting rehabilitation. Here too are endless opportunities for employment in the demolition of obsolete structures, clearing of land, reconstruction of streets and utility lines, and for privately refinanced redevelopment and planned communities.

At the upper end of the housing scale will be zero lotline homes, town houses, garden apartments, and low-rise multifamily apartments resembling horizontal condominiums. The separated single-family homes facing on local streets or culs-de-sac (with front yards devoted to display and side yards unused) will no doubt persist, but there will be a preponderance of dwellings with common walls and fenced or walled outdoor living areas.

Town houses are a long-standing tradition—from Boston and Philadelphia to San Francisco. Georgetown in Washington, D.C., surely one of the most delightful residential areas of our country, has narrow brick homes set wall to wall along its narrow, shaded streets. Its brick walk pavements, often extending from curb to facade, are opened here around the smooth trunk of a sycamore or punched out there to receive a holly, a boxwood, a flowering tree, or a bed of myrtle. In this compact community, where space is at such a premium, the open areas are artfully enclosed by fences, walls, or building wings to give privacy and to create a cool and pleasant well of garden space into which the dwelling opens.

Mid-to-lower-scale dwellings will also be designed in compact arrangements within open-space surroundings—with schools, child care centers, and convenience shopping close at hand. Again, some residential buildings will resemble horizontal habitats, with common laundries, storage spaces, gardens, and even kitchens. New concepts will be evident also in modular and prefab construction.

While the construction framing members and panels will be of uniform dimensions, the room shapes and arrangements can be of infinite variety—as can panel materials and finishes. Fixtures, equipment, and furnishings will be standardized but freely arranged within the living spaces. (This will be a modernized version of the age-old, economical, and delightfully varied Japanese modular approach to residential construction.) With wide front and side yard setbacks consolidated into shared usable space, the building groupings can be diverse and compact, with things to see and do close at hand. For most homeowners and tenants, this will be a desirable feature.

Relaxation of side-yard, setback, and enclosure restrictions will permit full use of lot, privacy, and indoor-outdoor transitions.

In working with urban renewal and model cities programs, we have discovered that the openness of newer communities was at first the thing with greatest appeal to families relocated from older neighborhoods or from cramped and aching slums. But the residents soon became dissatisfied with the severe buildings, the wide grass areas, and the play equipment set out on flat sheets of pavement. One would hear the officials ask, “What’s wrong with these people? Why aren’t they happy? What did they expect? What more do they want?”

What they wanted, what they missed, what they unconsciously longed for, were such congregating places as the carved and whittled storefront bench, the rear-porch stoops, the packed-clay, sun-drenched boccie courts, the crates and boxes set in the cool shade of a propped-up grape arbor or in the spattered shadow of a spreading ailanthus tree. They missed the meandering alleys, dim and pungent, the leaking hydrants, the hot, bright places against the moist, dark places, the cellar doors, the leaning board fences, the sagging gates, the maze of rickety outside stairs. They missed the torn circus posters, the rusting enameled tobacco signs, the blatant billboards, the splotchy patches of weathered paint. They missed the bakery smells of hot raisin bread and warm, sugared lunch rolls, the fish market smells, the clean, raw smell of gasoline, the smell of vulcanizing rubber. They missed the strident neighborhood sounds, the intermittent calls and chatter, the baby squalls, the supper shouts, the whistles, the “allee, allee oxen,” the pound of the stone hammer, the ring of the tire iron, the rumbling delivery truck, the huckster’s cart, the dripping, creaking ice wagon. They missed the shape, the pattern, the smells, the sounds, and the pulsing feel of life.

What they missed, what they need, is the compression, the interest, the variety, the surprises, and the casual, indefinable charm of the neighborhood that they left behind. This same charm of both tight and expansive spaces, of delightful variety, of delicious contrast, of the happy accident, is an essential quality of planning that we must constantly strive for. And one of the chief ingredients of charm, when we find it, is a sense of the diminutive, a feeling of pleasant compression. Private or community living spaces become a reality only if they and the life within them are kept within the scale of pleasurable human experience.

Minimum homes for maximum living.

Mixed use is nothing new. Tom Lamb, Lamb Studio

A further error of our planning has stemmed from the lingering compulsion to force our cities into lots and blocks of uniform size and use. Such “ideal” cities of monotonous conformity are gray in tone. If we examine most recent plans, we find that one zone is designated for single-family homes, another zone for town houses, and another for high-rise apartments; an isolated district is set aside for commercial use; a green area will someday be a park. May we place in this residential area an artist’s studio? It is not allowed! An office for an architect? A florist shop? A bookstall? A pastry shop? No! In a residential area such uses are usually not permitted, for that would be “spot zoning,” the bureaucratic sin of all planning sins. These have too often been the rules, and thus the rich complexities that are the very essence of the most pleasant urban areas of the world are even now still being regulated out of our gray cities. London, after the Blitz, was replanned and rebuilt substantially according to this antiseptic planning order. The first new London areas were spacious, clean, and orderly, and all would have seemed to be ideal except for one salient feature: they were incredibly dull. Nobody liked them. Our zoning ordinances, which to a large degree control our city patterns, are still rather new to us. They have great promise as an effective tool and a key to achieving cities of vitality, efficiency, and charm when we have learned to use them to ensure these qualities rather than preclude them.

The Outer City

In the replanned, far more efficient city diagram, the limits of the revitalized inner city will be defined by a circumferential parkway that provides external vehicular access, as well, to the satellite centers of the outer city.

In the expanding rings of previous outward growth, those districts farthest removed from the city center are usually newer, with many sound neighborhoods yet remaining. Without land regulation, however, most outer residential areas have been infiltrated by such incompatible uses as repair shops, used car lots, and truck stops, to name a few. These disparate uses are to be phased out—gathered into their own unified compounds, where they can operate more efficiently without disrupting their neighbors or the landscape.

It is in the outer city also where new satellite centers—as for health, education, business offices, manufacturing, and recreation—can take form at receptive sites surrounded by the communities of their employees. Such satellites connected center to center with intercity rapid transit and at the peripheries by the regional freeway and parkway circumferentials will attract those enterprises seeking togetherness in more conducive surroundings. Thus will be achieved far more efficient activity centers, with the advantage of nearby housing and optimum regional access. Such “centering” is believed to be the only means of ending the all-American scourge of urban sprawl.

Suburban sprawl. Barry W. Starke, EDA

It would seem that suburban living has become the American dream. The early abandonment of the industrialized city in search of greener pastures gained momentum until it became a rout. The migration was given impetus by the coming of the automobile and the expansion of highway networks. Moreover, as families and businesses pulled up stakes, city taxes were raised to compensate for the loss, while property values declined. The outward flight has continued until now many who work in the city and live in exurbia must spend hours a day in bucking traffic as they drive to and fro. It is only recently that the balance is beginning to tip. As suburban communities become commercialized and lose their appeal, and as revitalized cities become more attractive, there is an increasing back-to-the-city movement. As a result, the agricultural lands and forest beyond are less threatened. With the stemming of scatteration and the emerging acceptance of regional planning and redevelopment, we can in time have the best of all worlds—thriving cities, attractive suburbs, and a protected regional matrix of productive farmsteads, forest, and wilderness preserves.

Disastrous urban sprawl can be effectively preempted by investing in the fundamental systems that protect and nourish a healthy urban environment.

Dylan Todd Simonds

Freeway sculpture. Barry W. Starke, EDA; Barry W. Starke, EDA

Even more than the Industrial Revolution, even more than our threatening population explosion, even more than electronic technology, the automobile has been the chief determinant in American land planning for the past many years. In the foreseeable future this will probably yet be the case. Without a drastic change in our thinking, the automobile will continue to dominate our cities, our communities, and our lives. The challenge is to segregate and improve our trafficways while at the same time devising the means by which cohesive living and working areas may be freed of through-traffic intrusions.

The drivers and passengers of motorized vehicles are safest and happiest when the travel experience is one of flow through pleasant and variformed corridors. Street crossings and on-grade intersections are anathema to fast-moving traffic. They are to be avoided. By realigning expressways and arterial highways around, not through, residential and activity centers, the major causes of interruptions and accidents can be eliminated.

Where do city people like to be? Not where they feel intimidated by rushing traffic or the blank walls of massive office towers. Not where getting from here to there entails a long walk, wait, or tiresome climb. Not in a blazing or frigid windswept expanse of paving. Not where there is little of interest to see or do. People prefer instead to be in or move through ways and places of comfort, interest, and delight. They enjoy the meandering walk through contracting and expanding spaces. They enjoy the charm of diminutive nooks and passageways—of places where they can rest, to talk or people-watch. Such experiences are seldom happenstance; they must be thoughtfully planned.

With passage by Congress of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), there is now a national mandate to shape and reshape our living environment with the disadvantaged in mind. All people will benefit from such sensitive planning.

Well-designed ways and places, especially those intended for public use, accommodate everyone—not only the spry, but, as well, all who by reason of age or disability have special needs or problems. All of us in our lifetimes—from stroller days to the times of crutches, the cane, the walker or wheelchair—are “disadvantaged” to some degree in terms of mobility or cognizance.

Only in recent years have our public agencies and physical planners come to recognize the needs and possibilities, and take positive action. Now most building codes and regulations incorporate requirements designed to make life safer, more comfortable and convenient.

In general it can be said that in reviewing the merits of any architectural or landscape architectural proposal it should be tested vicariously by the experience of all potential users.

Among the more helpful innovations are well-marked, well-lighted pedestrian street crossings. Curbs at street corners are depressed and tapered. Ramped platforms are provided at bus stops to allow for the loading and unloading of passengers at the conveyance floor level. In parking courts, stalls are reserved near the entranceways for the use of the handicapped. Steps to public buildings and areas are being eliminated or alternative ramps installed with easy slopes and with handrails. Often entrance gates and doors are fully automated. Since many persons cannot read, or have language difficulties, the use of internationally standardized symbols has become a welcome feature of informational and directional signs.

The starkness of once-hostile downtowns has been relieved with shade tree plantings, miniparks, seating, fountains, and floral displays. Gradually our evolving metropolitan areas are taking form around interconnected, traffic-free business, shopping, and residential centers. On these well-furnished islands the experience of getting about, or being, in safe, attractive, and refreshing surroundings gives new meaning to town and city.

Few would deny that cities would be more pleasant if less bleak and more gardenlike. Is that asking too much of the system? Not when we can witness many examples of downtown transformation. Everywhere across the nation once-barren streets are now a-greening and a-blooming. Flower-bedecked planters, window boxes, and hanging baskets enframe store windows. Recessed bays and setbacks are converted to miniparks with raised planting beds and seating. Concrete boulevard medians are converted to seasonal showpieces. Vacant lots in the inner city are cleared of trash by citizen groups and with the help of civic groups or clubs made neighborhood gardens and gathering places.

The local embellishments are heartening signs of new attitudes. At the larger, citywide scale, publicized and aided tree-planting programs have clothed mile upon mile of streets and drives with burgeoning foliage. Polluted streambeds and riverbanks have been cleared of debris and restored to verdant waterways. Lakeshores and waterfronts have become a focus of public improvement and the focal points and pride of many cities.

Urban green/blue. Gustafson Guthrie Nichol Ltd.; Barry W. Starke, EDA; Belt Collins; Hirokazu Yokose/ Hargreaves Associates

Building upon such successes, sentiment is growing for open-space programs that will in time incorporate or consolidate large swaths and small bits and pieces of public land into integrated systems. Under the centralized guidance of expanded departments of parks, recreation, and open space, our contemporary cities might well in time come to approach the ideal of “an all-embracing garden-park within which buildings, travelled ways and gathering places are beautifully interspersed.”*5

But, one might ask, with urban real estate being sold by the square foot instead of the acre, how can such open space be afforded and assembled?

Hyatt City Center. Scott Shigley/Peter Lindsay Schaudt Landscape Architecture

In the center city the vacating of through and selected local streets would yield more than enough area for the ring-road bypass with its buffering parkland. The elimination of the divisive existing parking lots and structures can free up another 10 percent of the average CBD, as can the razing of half-used obsolete buildings. Reclaimed vacant or tax-delinquent lands can be added to park and recreation holdings. If within the city there are cliffs, steep slopes, or arroyos, so much the better. Where there are in-city streams or a waterfront, the possibilities are expanded.

Throughout the greater metropolitan confines, the evolving processes of reclamation, rehabilitation, and redevelopment will create extensive open-space reserves. To these can be added the gifts of property by public-spirited donors and the essential links and fill-in parcels acquired with bonds or budgeted capital improvement funds. The lands are there in various conditions ready to be put together into an open-space system and framework for ongoing development.

The needs of the human beings who would work and live in our cities must come to have precedence over the insistent requirements of traffic, over the despoiling demands of industry, and over the callous public acceptance of rigid economy as the most consistent criterion for our street and utility layouts and for the development of our boulevards, plazas, parks, and other public works.

What are the human needs of which we speak? Some have been so long ignored or forgotten in terms of city planning and growth that they may now seem quaint or archaic. Yet they are basic. We human beings need and must have once again in our cities a rich variety of spaces, each planned with sensitivity to best express and accommodate its function; spaces through which we may move with safety and with pleasure and in which we may congregate. We must have health, convenience, and mobility on scales as yet undreamed of. We also must have order. Not an antiseptic, stilted, or grandiose order of contrived geometric dullness or sweeping emptiness but a functional order that will hold the city together and make it work—an order as organic as that of the living cell, the leaf, and the tree. A sensed cohesive and satisfying order that permits the happy accident, is flexible, and combines the best of the old with the best of the new. An order that is sympathetic to those structures, things, and activities that afford interest, variety, surprise, and contrast and that have the power to “charm the heart.” We humans need in our cities sources of inspiration, stimulation, refreshment, beauty, and delight. We need and must have, in short, a salubrious, pollution-free urban environment conducive to the living of the whole, full life.

New urban area. © D.A. Horchner/Design Workshop

Such a city will not ignore nature. Rather, it will be integrated with nature. And it will invite nature back into its confines in the form of clean air, sunshine, water, foliage, breeze, wooded hills, rediscovered water edges, and interconnected garden parks.

Gradually, but with quickening tempo, the face of urban America is taking on a new look. It is a look of wholesome cleanliness, of mopping up, renovation, or tearing down and rebuilding. There is a sense of urgency, directness, nonpretense, and informality. There is a new group spirit of concerted actions and of people enjoying the experience of making things happen, of coming and being together in pleasant city surroundings. There is a freshness, sparkle, and spontaneity as American as apple pie. The movement was born partly of desperation—of the need by property owners to “save the city” and protect their threatened investments. It responds to the need for energy conservation and the contraction of overextended development patterns. It stems from revulsion at pollution, filth, decay, and delapidated structures. It is a strengthening compulsion to clean house, repair, and rebuild, mainly by private enterprise. There is a new vitality. There is a sense of competition, too, marked by inventiveness. Fresh winds are astir in our cities.

*5Kublai Khan, in outlining the plan for his new capital city, Tatu, the present-day Beijing.