In theory, architectural and engineering structures are conceived by their designers as the ideal resolution of purpose, time, and place. When this is achieved, the resulting structure—be it a cabin or cathedral, an aqueduct or amphitheater, a windmill, barn, or suspension bridge—is memorable for its artistry. The cities and landscapes of history are studded with such masterworks, many surviving as cherished cultural landmarks. It is fortunate that in contemporary times we may travel to study and learn from them—to understand their admirable traits and qualities.

What qualities, then, are common to the great examples?

It can be observed that, with few exceptions, at the time of their building, notable structures:

- Fulfilled and expressed their purpose—directly and with clarity.

- Reflected the cultural mores of their time, location, and users.

- Responded to the climate, the weather, and the dictates of seasons.

- Applied or extended the state-of-the-art current technology.

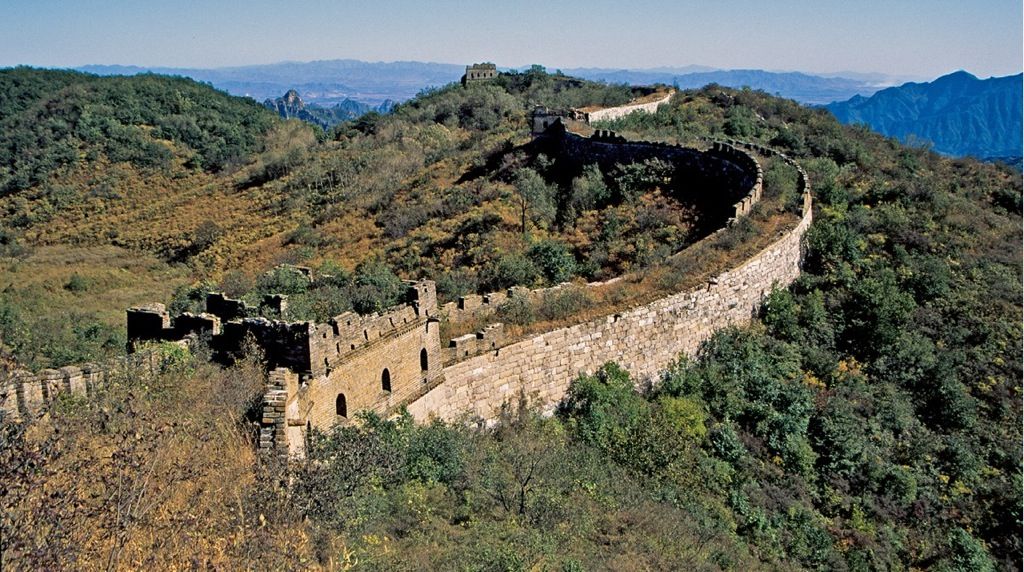

- Fitted compatibly into the built environs and the living landscape.

We have proposed that the adage, “Form follows function,” is valid only when it is understood that the term function transcends the delimiting connotation of “utilitarian.” The term function in the context of expressive design is comprehensive and includes such considerations as traditional values, ethics, aesthetic quality, feasibility, acceptability, and fitness. Only if all such requisites are satisfied can it be said of a structure or form that it truly fulfills its intended function or purpose.

We contemporaries proceed in blithe disregard of the truths and lessons of history. If we, proud spirits that we are must learn our truth firsthand, there need be no problem, for we are surrounded by examples of the good and the bad and need only develop a discerning eye to distinguish art from error.

A building is a thing in itself. It has a right to be there, as it is, and together with nature, a compensation of contrasts.

Marcel Breuer

Architecture subtly and eloquently inserts itself into the site, absorbing its power to move us and in return offering to it the symphonic elements of human geometry.

Le Corbusier

Culture

The culture of a community or nation is an evolving state of being or communal mind-set. It implies, sometimes overkindly, a certain level of civilization. As such, it is at any given time the manifestation of a people’s beliefs and aspirations—those ideas or things that are acceptable and those that are not. This cultural litmus test is by custom applied not only to dress, foods, and works of music, literature, and art—but perhaps most particularly to buildings and other structures.

Cultural approbation allows for obvious improvement and some innovation—but rejects vociferously, and sometimes violently, that which seems out of place or offensive. This being so, it would follow that the architect, engineer, or landscape architect in the planning stage might well take pains to ensure, insofar as possible, public approval and acceptance.

Successful structures and planned landscapes not only conform to discerning public taste; they serve to upgrade and refine it.

Locality

Masterful structures are an expression of place. They respond to and grow out of their site. They accentuate its positive qualities. At best, the design of structures is a highly developed exercise in creative synergy. Sensitive design reflects, distills, and often makes more dramatic the indigenous landscape character. It utilizes every favorable aspect of the topography. It is aware of and braces for the directional winds and storm. It opens out to the breeze and favorable views. It traces the orbit of the sun. It designs into and composes with the adjacent built environment. The mark of a well-conceived structure is that it enhances, rather than degrades, its site and surroundings.

Technology

Architecture, engineering, and landscape architecture are at the same time an art and a science. The art has to do mainly with visual qualities—craftsmanship, composition, and the appearance of things. Science entails the organization of structural and mechanical systems and the satisfaction of human needs, all in accordance with the timeless laws and principles of nature.

Technology in recent years has advanced with astounding rapidity. In the design of structures, for example, it was not long ago that prestressed concrete was unknown, as was steel reinforcing, electronics—or even electricity, for that matter. Now, with a broad range of new materials and construction techniques, the possibilities have expanded manyfold. With the emergence of computer technology the design of physical structures has taken on new dimensions.

Environs

What have these advances contributed to the betterment of our environment? Not much that is evident. Not yet at least. We can get around faster, build higher, and communicate with the speed of light. But many would hold that the net results of our building in this age of mechanical marvels has been to trash and grievously pollute not only our immediate living environment, but the greater continental land masses, the depths of the seas that surround them, and the atmosphere as well. Clearly, our technical and structural capabilities have outstripped our ability to envision and realize a world in which structures are conceived and built in full awareness of nature’s forms and forces—and in harmony with the living Earth. A critical change of course is the challenge of our times.

This rage for isolating everything is truly a modern sickness.

Camillo Sitte

We physical planners like to think of ourselves as masters of space organization, yet in truth we are often baffled by the simplest problems of spatial arrangement and structural composition. What, for instance, are the design considerations in relating a building to its surrounding sea of space or to its fronting approaches, or two buildings facing each other across an intervening mall, or a group of structures to each other and the spaces they enclose? Let us start from the beginning.

Composition of structures. When a structure is to be related to a given area or space, both the shape and the character of the area or space will be affected by the positioning of the structure.

Building composition forms outdoor space. Tom Lamb, Lamb Studio

Buildings and Spaces

If we were to place a building on a ground plane, for instance, how much space should we allow around it? First, we will want to see it well from its approaches. The spaces about it should not only be large enough or small enough but also of the right shape and spatial quality to compose with the structure and best display it. We want to be sure that enough room is allowed to accommodate all the building’s exterior functions, including approaches, parking and service areas, courts, patios, terraces, recreation areas, or gardens. Such spaces are volumetric expressions of the site-structure diagram. We want to be certain that the structure and its surrounding spaces are in toto a complete and balanced composition. Just as all buildings have purpose, so should the open spaces that they define or enclose. Such spaces must be clearly related to the character, mass, and purpose of the structures.

We need desperately to relearn the art of disposing of buildings to create different kinds of space: the quiet, enclosed, isolated, shaded space; the hustling, bustling space pungent with vitality; the paved, dignified, vast, sumptuous, even awe-inspiring space; the mysterious space, the transition space which defines, separates and yet joins juxtaposed spaces of contrasting character.

We need sequences of space which arouse one’s curiosity, give a sense of anticipation, which beckon and impel us to rush forward to find that releasing space which dominates, which climaxes and acts as a magnet, and gives direction.

Paul Rudolph

Often the form of a building itself is not as important as the nature of the exterior space or spaces that it creates. The portrait painter knows that the outline of a figure or the profile of a head is sometimes secondary to the shape of the spaces created between figure or head and the surrounding pictorial enframement; it is the relationship of the figure to the surrounding shapes that gives the figure its essential meaning. So it is with buildings. Our buildings are to be spaced out in the landscape in such a way as to permit full and meaningful integration with other structures and spaces and with the landscape itself.

Groups of Structures

When two or more buildings are related, the buildings, together with the interrelated spaces, become an architectural entity. In such a situation, each structure, aside from its primary function has many secondary functions in relation to the assemblage.

Composition of structures. Often the form of the structures themselves is not as important as that of the spaces they enclose. A single structure is perceived as an object in space. Two or more structures are perceived not alone as objects but also as related objects, and they gain or lose much of their significance in the relationship.

Spatial penetration of structure.

The buildings are arranged to shape and define exterior volumes in the best way possible. They may be placed:

As enclosing elements

As screening elements

As backdrop elements

To dominate the landscape

To organize the landscape

To command the landscape

To embrace the landscape

To enframe the landscape

To create a new and controlled landscape

To orient the new landscape outward or inward

To dramatize the enclosing structures

To dramatize the enclosed space or spaces

To dramatize some feature or features within the space

They are placed, in short, to develop closed or semienclosed spaces that best express and accommodate their function, that best reveal the structural form, facade, or other features of the surrounding structures, and that best relate the group as a whole to the total extensional landscape.

An isolated city dwelling, suspended as it were in space, is but a Utopian dream. City dwellings should always be considered as the component parts of groups of structures, or districts.

José Luis Sert

We have seen too often in our day a building rising on its site in proud and utter disdain of its neighbors or its position. We search in vain for any of those relationships of form, material, or treatment that would compose it with the existing elements of the local scene. Such insensitive planning would have been incomprehensible to the ancient Greeks or Romans, who conceived each new structure as a compositional element of the street, forum, or square. They did not simply erect a new temple, a new fountain, or even a new lantern; they consciously redesigned the street or square. Each new structure and each new space were contrived as integral and balanced parts of the immediate and extensional environment. These planners knew no other way. And in truth, there can be no other way if our buildings and our cities are again to please and satisfy us.

For as there cannot be a socially healthy population consisting only of egotistic individualists having no common spirit, so there cannot be an architecturally healthy community consisting of self-sufficient buildings.

Eliel Saarinen

Building dominates the urban landscape. Barry W. Starke, EDA

Each building or structure as a solid requires for its fullest expression a satisfying counterbalance of negative open space. This truth, of all planning truths, is perhaps the most difficult to comprehend. It has been comprehended and mastered in many periods and places—by the builders of the Karnak Temple, Kyoto’s Katsura Palace, or the gardens of Soochow (Suzhou), for example. We still find their groupings of buildings and interrelated spaces to be of supremely satisfying harmony and balance; each solid has its void, each building has its satisfying measure of space, and each interior function has its exterior extension, generation, or resolution of the function.

What do we contemporary planners know of this art or its principles, which have been evolved through centuries of trial and error, modification, reappraisal, and patient refinement? The orientals have a highly developed planning discipline that deals with such matters in terms of tension and repose. Though its tenets are veiled in religious mysticism, its plan applications are clear. It is a conscious effort in all systems of composition to attain a sense of repose through the occult balance of all plan elements, whether viewed as in a pictorial composition or experienced in three dimensions:

The near balanced against the far

The solid against the void

The light against the dark

The bright against the dull

The familiar against the strange

The dominant against the recessive

The active against the passive

The fluid against the fixed

In each instance, the most telling dynamic tensions are sought out or arranged to give maximum meaning to all opposing elements and the total scheme. Though repose through equilibrium must be the end result, it is the relationship of the plan elements through which repose is achieved that is of utmost interest. It is the contrived opposition of elements, the studied interplay of tensions, and the sensed resolution of these tensions that, when fully comprehended, are most keenly enjoyed.

Opposing structures generate a field of dynamic tension.

A group of structures may be planned in opposition both to each other and to the landscape in which they rise, so that as one moves through or about them, one experiences an evolving composition of opposing elements, a resolution of tensions, and a sense of dynamic repose. A single tree may be so placed and trained as to hold a distant forest or group of smaller trees in balanced opposition and give them richer meaning. A lake shining deep and still in the natural bowl of a valley may, by its area, conformation, and other qualities, real or associative, hold in balanced repose the opposing hills that surround it. A plume of falling water at the lake’s far end may balance the undulations of its points and bays.

Walter Beck, long a student of oriental art and composition, has said of the superb gardens that he planned at Innisfree: “On a wall, at the lake edge, is a rock which I call the dragon rock; it is the key in a grouping of stones whose function is to hold in balance the lake and nearby hills; whose function is to cope with the energies of the sky and the distant landscape.”*6 It can be seen that tremendous compositional interest and power can be concentrated in such key objects—rocks, sculpture, structures, or whatever you will—that by design may hold a great system of elements in balanced tension and thus in dynamic repose.

It would seem, from a comparison of the European and oriental systems of planning, that the Western mind is traditionally concerned primarily with the object or structure as it appears in space, while the Eastern mind tends to think of structure primarily as a means of defining and articulating a space or a complex of spaces.

In this light, Steen Rasmussen, in his book Towns and Buildings, has made a revealing graphic comparison of two imperial parks, that of King Louis XIV at Versailles and the Sea Palace Gardens in Beijing. Both were completed in the early 1700s, both made use of huge artificial bodies of water, and both were immense; but there the similarity ends. A close study of these two diametrically opposed planning approaches, illustrated here, will lead one to a fuller understanding of the philosophy of both occidental and oriental planning in this period of history.

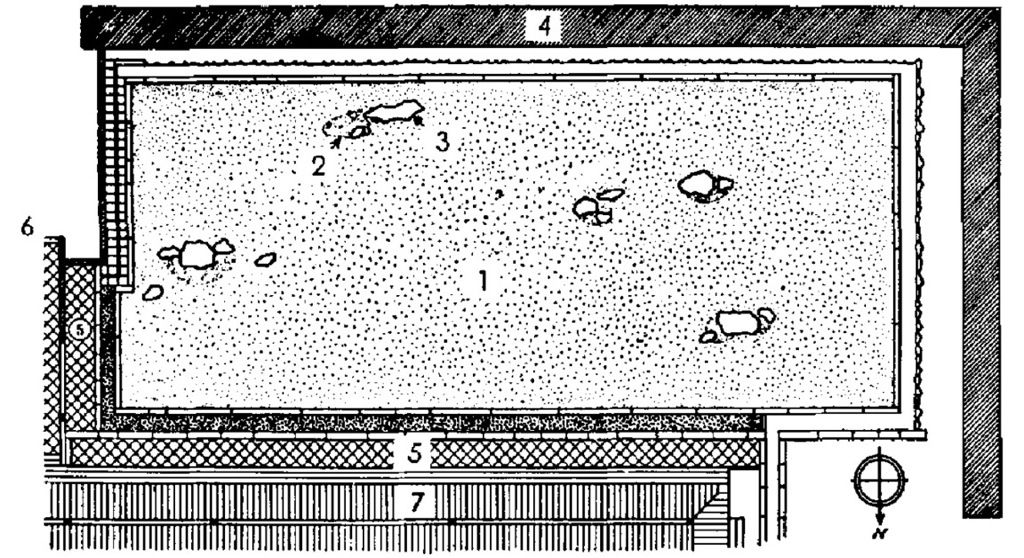

Peking, Sea Palace gardens.

Versailles Park.

Too often, when placing or composing structures in space we revert to cold geometry. Our architectural libraries are bulging with building plans and diagrams laid out in crisp, abstract patterns of black and white that have little meaning except in the flat. It is small wonder that buildings that take their substance from such plans are destined to failure, for they were never conceived in terms of form in space or of spaces within form. The world is cluttered with such unfortunate travesties. The intelligent planning of buildings, parks, and cities is a far cry from such geometric doodling. A logical plan in two dimensions is a record of logical thinking in three dimensions. The enlightened planner is thinking always of space-structure composition. His or her concern is not with the plan forms and spaces as they appear on the drawings but rather with these forms and spaces as they will be experienced in actuality.

Many Renaissance squares, parks, and palaces are little more than dull geometry seen in the round. One clear, strong voice crying out against such puerile design was that of Camillo Sitte, a Viennese architect whose writings on city building first appeared in 1889 and whose ideas are still valid and compelling today. It was Sitte who pointed out that pre-Renaissance people used their public spaces and that these spaces and the buildings around them were planned together to satisfy the use. There were market squares, religious squares, ducal squares, civic squares, and others of many varieties; and each, from inception through the numerous changes of time, maintained its own distinctive quality. These public places were never symmetrical, nor were they entered by wide, axial streets that would have destroyed their essential attribute of enclosure. Rather, they were asymmetrical; they were entered by narrow, winding ways. Each building or object within the space was planned to and for the space and the streams of pedestrian traffic that would converge and merge there. The centers of such spaces were left open; the monuments, fountains, and sculpture that were so much a part of them were placed on islands in the traffic pattern, off building corners, against blank walls, and beside the entryways, each positioned with infinite care in relation to surfaces, masses, and space. Seldom were such objects set on axis with the approach to a building or its entrance, for it was felt that they would detract from the full appreciation of the architecture. Conversely, it was felt that the axis of a building was seldom a proper background for a work of art.

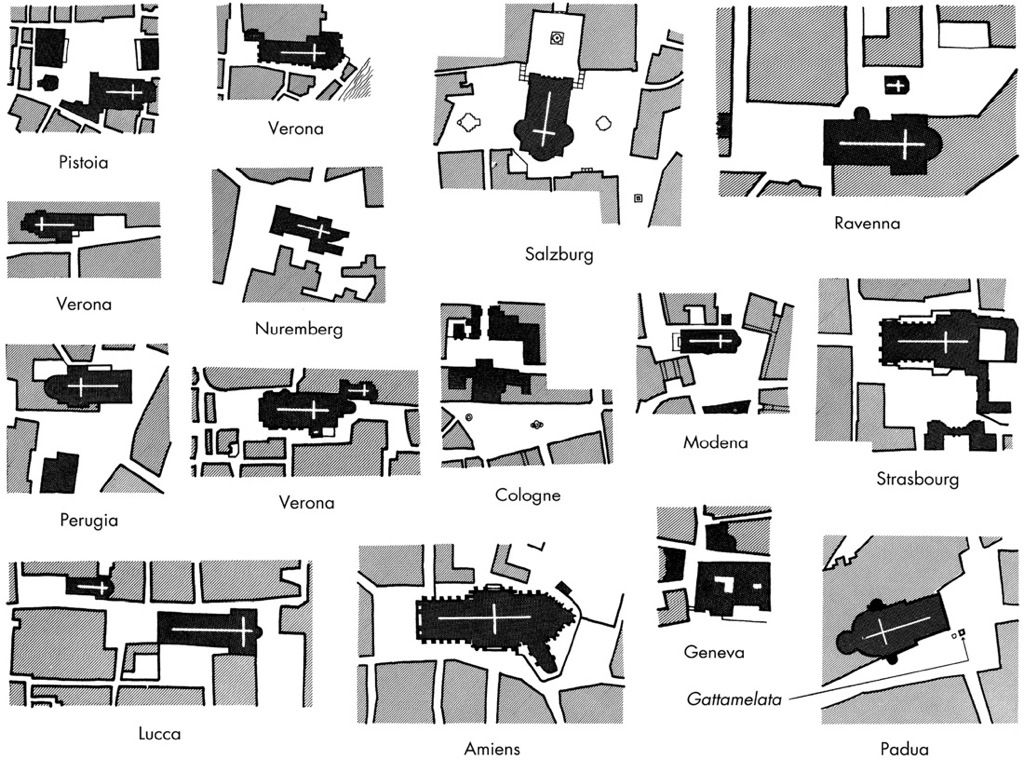

Sitte discovered that such important buildings as cathedrals were rarely placed at the center of an open space, as we almost invariably place them today. Instead, they were set back against other buildings or off to the side to give a better view of facade, spires, or portals and to give the best impression from within the square or from its meandering approaches.

Rules of Composition

Down through the centuries, much thought has been given to the establishment of fixed formulas or rules that might govern building proportions, or the relationship of one building to another, or the relationship of a building to its surrounding volumetric enclosure.

The location of the equestrian statue of Gattamelata by Donatello in front of Saint Anthony of Padua is most instructive. First we may be astonished at its great variance from our rigid modern system, but it is quickly and strikingly seen that the monument in this place produces a majestic effect. Finally we become convinced that removed to the center of the square its effect would be greatly diminished. We cease to wonder at its orientation and other locational advantages once this principle becomes familiar.

The ancient Egyptians understood this principle, for as Gattamelata and the little stand beside the entrance to the Cathedral of Padua, the obelisks and the statues of the Pharaohs are aligned beside the temple doors. There is the entire secret that we refuse to decipher today.

Camillo Sitte

There have long been those who believe that mathematics is the all-pervading basis of our world of matter, growth, and order. To them, it has followed naturally that order, beauty, and even truth are functions of mathematical law and proportion. The golden rectangle, for example, has long been a favorite of mathematicians, perhaps because of the fact that if a unit square is subtracted from each ever-diminishing rectangle, a golden rectangle each time remains. This “ideal” rectilinear shape (whose sides have a ratio of 1:1.618, or roughly 3:5) has appeared again and again, in plan and in elevation, in the structures and formed spaces of the western world.

Miloutine Borissavlievitch, in his absorbing work, The Golden Number, has explored its application to architectural composition. He proposes that although the golden rectangle considered by itself is, both philosophically and aesthetically, the most beautiful among all horizontal rectangles, “when considered as a part of a whole, it is neither more beautiful nor unattractive than any other rectangle. Because a whole is ruled by the laws of harmony, by the ratios between the parts and not by a single part considered by itself.” He notes that “Order is indeed the greatest and most general of esthetic laws,” and then suggests that there are only two laws of architectural harmony: the law of the same and the law of the similar.*7

The law of the same. Architectural harmony may be perceived or created in a structure or composition of structures that attains order through the repetition of the same elements, forms, or spaces.

The law of the similar. Architectural harmony may be perceived or created in a composition that attains order through the repetition of similar elements, forms, or spaces.

Borissavlievitch notes that “whilst the Law of the Same represents unity (or harmony) in uniformity, the Law of the Similar represents unity in variety.” He wisely notes also that “an artist will create beautiful works only in obeying unconsciously one of these two laws. Whilst we create, we do not think about them, and we follow only our imagination and our artistic feeling. But when our sketch is made, we look at it and examine it as if we were its first spectator and not its creator, and if it is successful we shall know, because of our knowledge of these laws why it is successful; if it is not, we shall know the reason of the failure.”

“The beautiful,” said Borissavlievitch, “is felt and not calculated.”

Leonardo Fibonacci, an Italian mathematician of the thirteenth century, discovered a progression that was soon widely adapted to all phases of planning. He noted that starting with units 1 and 2, if each new digit is made the sum of the previous two, there results a progression of 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, and so forth, which, translated into plan forms and rhythms, is visually pleasing. It was later discovered that the progression approximates the growth sequence of plants and other organisms; this, of course, added to its interest and confirmed in the minds of designers the notion that this progression is “natural” and “organic.”

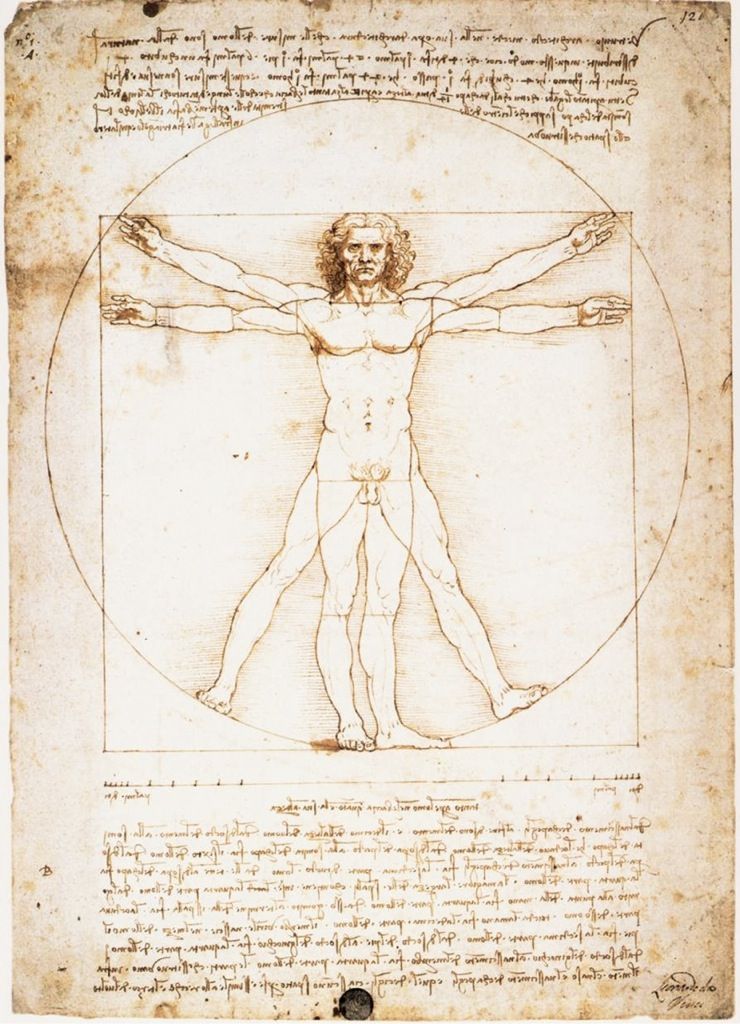

Marcus Vitruvius, a Roman architect and scholar who lived in the first century before Christ, set out to formulate a system of proportion that he could apply to his plans and structures. In his search he undertook an exhaustive study of the architecture and planning of ancient Greece. In the course of his work he produced a book setting forth his findings and expounding his theories on the anthropomorphic module, a unit of measurement based on the proportions of the human body. This was to have a profound effect on the thinking and planning of the Renaissance.

Leonardo da Vinci, the creative giant of his time, analyzed and tabulated his own system of mean proportions of the component parts of the human figure in relation to its total height and then derived a table of classic proportions and ratios from which he developed for each project a suitable modular system. As architect-engineer-sculptor-painter, he translated his findings into all his works and through them demonstrated to posterity his conviction that, to achieve order and beautiful proportion in any work, the major masses or lines and the smallest detail must have a consistent mathematical relationship.

Vitruvian Man: A study by Leonardo da Vinci from one of his notebooks illustrating his principle, “The span of the man’s outstanding arms is equal to his height.” Leonardo da Vinci

The conviction that architecture is a science and that each part of a building has to be integrated into one and the same system of mathematical ratios may be called the basic axiom of Renaissance architects. Today, we physical planners are still searching for the modular system most applicable to our contemporary work. One of the distinguishing marks of Japanese planning and architecture is a fundamental order, or mathematical relationship, of the elements. This stems, at least in part; from the use of the tatami, or woven grass mat (approximately 3 by 6 feet), as a standardized unit of measurement. Traditionally, a modular grid system based upon this unit has been the foundation of most building plans and surrounding spaces. By this system, a room is a given number of mats in length and width, and a building plan is so many mats in area. In their planning, the Japanese make use also of the 12-foot dimension, which is divisible by 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6.

The Vitruvian figure inscribed in a circle and square became a symbol of the mathematical sympathy between macrocosm and microcosm.

Rudolph Wittkower

If a unit such as a closet or a case requires less than the full module, it is not distorted to fill the module; rather, it is set free within the module and composed within the modular framework. The fact that an object is smaller or larger than the module is not concealed but is artistically revealed and elucidated. This approach would seem to be clearly superior to our American modular systems by which components are designed (or forced) to fit precisely within a given structural grid. The Japanese form order also differs significantly from the rigid geometric planning of Europe’s Renaissance, which worshiped insistent symmetry rather than such a free and flexible system of modular organization.

We have seen how the ancients struggled with the visual aspects of architectural composition, of trying to create a fairer world in their own rational image. They found within the mathematical context no universal rules except those of order, proportion, and scale. Could it be that in their compulsion to measure, compare, and debate they overlooked the ultimate truth so evident in all of nature’s structures? This is the law of fitness. The law of fitness would reveal to us that the optimum structure, of any type, is that which for its time and place and with the most economical use of materials best fulfills its purpose.

Without exception nature has fashioned, in the mast-and-spar construction of each tree, the skeleton of each animal or bird, each eggshell, and each weed stalk, a structure of utmost simplicity, strength, and resilience. Each as a form is eminently suited to its function. Each is designed and engineered without concern for aesthetics, yet each, in its absolute fitness, is intrinsically beautiful. Could it be that a dogma of rules and formulas could preclude rather than foster meaningful design? Could it be that a preconceived notion of plan form and structural shapes could produce archaic buildings? Could it be that, as in nature, our most ingenious and handsome structures will be derived in a forthright search for ever more expressive form? It could be. The unselfconscious architecture of the New England farm, the Greek hill town, and the African council house all share nature’s direct approach, and all, in their ways, are eloquently expressive.

Composition of structures. The number of polar relationships increases arithmetically with the addition of each unit to a complex of structures. Since each new unit modifies the composition, its relationship to all other units is a matter of design and planning concern.

As with structural forms and objects, nature has much to teach us, as well, in the plan layout of our homes and cities. We have yet to see an axial anthill or a symmetrical plan arrangement of a beaver colony. The creatures of the wild have learned to fit their habitations to the natural land conformation, to established patterns of water flow, to the force and direction of the winds, and to the orbit of the sun. Should not we be as responsive?

Yet we have all seen towers with expanses of metal and heat-absorbing glass focused into the rays of the sun. We are all too familiar with broad avenues aligned to receive, unchecked, the full blast of prevailing winter winds. We recall groupings of campus buildings which have completely destroyed the natural character of the hills and ravines upon which they have been imposed. We know of checkerboard communities laid out in utter disdain of contours, watercourses, or wooded slopes, or geology, storm, or view.

If there be a lesson, it is this: Architecture by formula and site planning by sterile geometry are equally doomed to failure.

Individual buildings are sometimes spaced out as deployed units of a greater architectural composition. It can be seen that such structures and the spaces they define combine to give a more telling impact than would be possible for any single structure of the group. Sometimes this is desirable; sometimes it is not. Such an arrangement of structures seems most reasonable when each building not only appears but also functions as a part of the total complex. In every case in which a building serves as a unit of an architectural group, the entire group is treated as a cohesive and unified composition, and each structure owes allegiance to the whole.

Integration of structures.

Classification by the addition of structural elements plus definitive circulation ways.

Diverse plan elements related by circulation patterns.

Buildings may be arranged freely in the landscape as individual units. In such cases, when they need not be planned as part of a complex, they and the spaces around them may be designed with much more freedom. Their relationship is not one of building to building but rather one of building to landscape, with all that this implies.

Buildings of similar character may be dispersed, even at considerable distances, in such a manner as to dominate a landscape and unify it—as in a university campus or military installation. Though a great variety of uses may be given to the intervening landscape areas, each element within the visual field must be compatible by association.

Planned building composition. Tom Fox, SWA Group

Structures are often composed in relation to natural or constructed elements of the landscape, such as a water body, a railroad siding, or a highway. In such cases, the buildings, singly or in composite, may be given their form and spacing to achieve the best possible relationships. A resort complex and its fronting lake are in effect composed as an interrelated unit, in which the lake adds much to the resort and resort, in turn, adds to the ambience of the lake.

A factory and its receiving and shipping yards are designed to and with the railroad. A roadside restaurant is planned as one with the highway in terms of landscape character, sight distances, approaches, resolution of momentums, and composition of spaces and forms.

It is to be remembered that a building complex, as much as a natural forest grove, has its own landscape character. This must be recognized if it is to be accentuated by the planned relationships and supporting site treatment.

Various compositional arrangements of apartment structures.

Some buildings are static. They stand aloof and are complete in themselves. Such structures are no doubt valid when the intended architectural expression is that of detachment, grandeur, the austere, or the monumental. They require that their setting and site development be in keeping.

Other building groupings, by their very plan layout, seem to express human freedom and interaction. They form a responsive relationship with nature and the constructed landscape. It can be seen that not only the structures themselves but also their abstract arrangement determine to a large degree their character and the character of the larger landscape area that they influence or embrace.

Often, scattered buildings may be brought into a more workable and visually satisfying relationship by connecting them with paved areas or by well-defined lines of circulation. Again, this integration may be accomplished by the addition of structural elements such as walls or fences. Sometimes tree rows or even hedges may suffice to bind them together. The elements that unite such structures may at the same time define for each the most fitting volumes of related space.

Open spaces assume an architectural character when they are enclosed in full or in part by structural elements. Such a space may be an extension of a building. Sometimes it is confined within the limits of a single building or enclosed by a building group. Sometimes such a space surrounds a structure or serves as its foreground, as a foil, or as a focal point. Each such defined open space is an entity, complete within itself. But more, it is an inseparable part of each adjacent space or structure. It can be seen that such related spaces, structures, and the landscape that surrounds them must all be considered together in the process of design.

A defined outdoor volume is a well of space. Its very hollowness is its essential quality. Without the corresponding void, a solid has no meaning. Is it not then quite evident that the size, shape, and quality of the negative space will have a powerful retroactive effect upon the adjacent positive masses? Each structure requires for its fullest expression a satisfying balance of mass and void. The same void may not only satisfy two or more solids and relate them to each other, it may also relate them as a group to some further structures or spaces beyond.

Architecture defines open space. Kongjian Yu/Turenscape; Belt Collins; City of Vancouver

Whatever its function, when the hollowness of a volume is a quality to be desired, this concavity is to be meticulously preserved and emphasized by letting the shell read clearly, by revealing enclosing members and planes, by incurving, by belling out the sides, by the use of recessive colors and forms, by letting the bottom fall away visually, by terracing or sloping down into and up out of the base, by digging the pit, or by depressing a water basin or reflective pool and thus extending the apparent depth of the space to infinity. A cleanly shaped space is not to be choked or clogged with plants or other standing objects. This is not to imply that the volume should be kept empty, but rather that its hollowness should be in all ways maintained. A well-placed arrangement of elements or even a clump or grove of high-crowned trees might well increase this sense of shell-like hollowness.

The defined space, open to the sky, has the obvious advantages of flooding sunlight, shadow patterns, airiness, sky color, and the beauty of moving clouds. It has disadvantages, too, but we need only plan to minimize these and to capitalize on every beneficial aspect of the openness. Let us not waste one precious yard of azure blue, one glorious burst of sunshine, or one puff of welcome summer breeze that can be caught and made to animate, illuminate, or aerate this outdoor volume that we plan.

If the volume defined by a structure is open to the side, it becomes the focal transition between the structure and the landscape. If open to the view, it is usually developed as the best possible viewing station and the best possible enframement for the view seen from the various points of observation.

Abstract composition. The garden of Ryōanji, Kyoto, surely one of the 10 outstanding gardens of all time, is an abstract composition of raked gravel simulating the sea. The walled space expands the limits of the related monastery refectory and terrace. Designed as a garden for contemplation, it owes its distinction to its simplicity, its perfection of detail, its suggestion of vast spaces, and its power to set free the human mind and spirit. Barry W. Starke, EDA

The defined open space is normally developed for some use. It may extend the function of a structure, as the motor court extends the entrance hall or as the dining court extends the dining room or kitchen. It may serve a separate function in itself, as does a recreation court in a dormitory grouping or a military parade ground flanked by barracks. But whether or not it is directly related to its structure in use, it must be in character. Such spaces, be they patios, courts, or public squares, become so dominant and focal in most architectural groupings that the very essence of the adjacent structures is distilled and captured there.

(1) Sanded ground, (2) moss, (3) stone, (4) earth wall, (5) tile pavement, (6) ornamental gate, and (7) veranda.

What does a dwelling want to be? Shelter? Family activity center? Base of operations? All three, no doubt, and each of these functions is to be expressed and facilitated. But in its fullest sense a habitation is much more. It is our human fix on the planet Earth, our earthly abode. Once accepted, this simple philosophic concept has far-reaching implications.

In the planning of their homes and gardens, Asians not only adapt them with great artistry to the natural landscape but also consciously root them in nature. Constructed of materials derived from the earth (with varying degrees of tooling and refinement), these homes and gardens are humanized extensions of earth form and structure and are fully attuned to the natural processes. Like the nest of the bird or the beaver’s lodge, they are nature particularized.

It is proposed that each human habitation is best conceived as an integral component of the natural site and landscape environs. The extent to which this can be accomplished is a measure of the dwelling’s success and the occupant’s sense of fitness and well-being.

This integration of habitation with nature is an exacting enterprise. How is it to be achieved? As a beginning:

Explore and analyze the site. Just as the bird or the animal scouts the territory for the optimum situation, just as the farmer surveys the holding and lays out fields and buildings to conform to the lay of the land, just so must the planner of each home and garden come to know and respond to the unique and compelling conditions of the selected site.

Adapt to the geological structure. The conformation of every land area is determined largely by its geologic formation—the convolutions, layering, upheavals, erosion, and weathering of the underlying strata. These establish the stability and load-bearing capacity of the various site areas and the ease or difficulty of excavation and grading. They determine as well the structure, porosity, and fertility of the subsoil and topsoil, the presence of groundwater, and the availability of freshwater reserves. Only with the knowledge of subsurface conditions, gained by test holes or drilling or the keen eye of experience, can one plan to the site with assurance.

Take advantage of natural site characteristics. Tom Lamb, Lamb Studio

Preserve the natural systems. Topography, drainageways, waterways, vegetative covers, bird and wildlife trails and habitat all have continuity. One test of good land planning is that it minimizes disruption of established patterns and flows.

Adjust the plan to fit the land. In the recomposition of solids and voids the structural elements are usually designed to extend the hill or ridge and overlook the valley. Well-conceived plan forms honor and articulate the basic land contours and water edges. The prominence is made more dominant, the hollow and cove more recessive.

Reflect the climatic condition. Cold, temperate, hot-dry, or warm-humid, each broad climatic range brings to mind at once planning problems and possibilities. Within each range, however, there are many subarea variations of climate or site-specific microclimate that have direct planning implications.

Design in response to the elements. Protect from the wind. Invite the breeze. Accommodate the rain or snow. Avoid the flood. Brace for the storm. Trace and respond to the arcing sun.

Consider the human factors. On- and off-site structures, trafficways, utility installations, easements, and even such givens as social characteristics, political jurisdictions, zoning, covenants, restrictions, and regulations may have a telling influence.

Eliminate the negatives. Insofar as possible, all undesirable features are to be removed or their impacts abated. The undesirables include pollution in its many aspects, hazards, and visual detractions. When they cannot be eliminated, they are mitigated by ground forms, vegetation, distance, or visual screening.

Accentuate the best features. Fit the paths of movement, use areas, and structures around and between the landscape superlatives. Protect them, face toward them, focus upon them, enframe them, and enjoy them in all conditions of light and in all seasons.

Let the native character set the theme. Every landscape area has its own mood and character. Presumably, these were among the chief reasons for the site selection. Only if the indigenous quality is not desirable or suited to the project use should it be significantly altered. Otherwise, design in harmony with the theme, devising pleasant modulations, light counterpoint, and resonant overtones.

Integrate. Bring all the elements together in the best possible dynamic relationships. This is the lesson of nature. This is the primary objective of all planning and design.

Whatever the type of dwelling, be it a single-family home, a townhome unit with garden court, or a tower apartment … whatever the location, be the site urban or rural, mountain or plain, desert or lakeside … the planning approach is the same.

What would the ideal garden home be like? As a clue, observation will teach us that at least the following requirements of most home dwellers should be satisfied.

Shelter

The contemporary home, like all before it, is first of all a refuge from the storm. With the advent of sophisticated heating devices, climate controls, diversified construction materials, and ingenious structural systems, the concept of shelter had been brought to a new high level of refinement. But architecturally this basic function of shelter is to be served and given clear expression.

This implies safety from all forms of danger, not only from the elements but from fire, flood, and intruders as well. Although the nature of potential threats has changed through the centuries, our instincts have not. Safety must be implicit.

Today, an ever-present hazard is that of the moving vehicle with its backings and turnings. It does not belong within our living areas and should not be admitted. The automobile should be stabled within its own service area or compound.

Utility

Each dwelling should be a lucid statement of the various purposes to be served. Not only is each use to be accommodated, it is to be conveniently related to all others. And what are these uses? They are those of food preparation, dining, entertaining, sleeping, and (perhaps) child rearing. These uses are supplemented by the library, correspondence corner, workshop, laundry … and supported by storage spaces, mechanical equipment, and waste disposal systems. Often, much of the home entertainment and relaxation takes place on the balcony, lawn, or terrace. The outdoor spaces also provide healthful exercise and satisfy our agricultural yearnings. Even the pot of chives or the parsley bed has its important symbolic meaning.

Utility connotes “a place for everything, and everything in its place,” all working well together. While a home is far more than a machine for living, it must function efficiently.

Evolution of a way of life.

Amenity

It is not enough that a dwelling works well. It must also be attractive and pleasant. It must satisfy the human bent for display and our love of beautiful objects. Beauty is not, however, to be confused with decoration, ornamentation, or the elaborate. True beauty is most often discerned in that which is utterly simple and unpretentious—a well-formed clay pot, a simple carpet of blended wools, handsomely fitted and finished wood, cut slate, handcrafted silver—always just the right form, material, and finish to serve the specific purpose, always the understatement, for less is truly more.

In considering dwellings and display, mention should be made of the tokonoma of the traditional Japanese home. Constructed of natural materials of elegant simplicity, the tokonoma is a place reserved for the sharing of beautiful objects. These objets d’art are selected from storage cabinets or gathered from the garden or site and brought out, a few at most at one time, to mark the season or a special occasion. They may include hangings, paintings, a bowl, sculpture, or a vase or tray to receive a floral arrangement. Our Western homes and gardens and their displays could well be distinguished by such artistry and restraint.

Buildings as part of the landscape. © D.A. Horchner/Design Workshop

Privacy

In a world of hustle and hassle, we all need, sometimes desperately, a place of quiet retreat. It need not be large—a space in the home or garden set apart from normal activities where one can share the enjoyment of reading, music, or conversation or turn for quiet introspection. It is very human to feel the need for one’s own private space.

A Sense of Spaciousness

Just as we feel the need to retreat, we feel also upon occasion the need for expansive freedom. With dwelling and neighborhoods becoming more and more constricted, such spaciousness inside property limits is almost a rarity. But we can learn from those cultures in which people have lived for centuries in forced compression that space can be “borrowed.”

Spring rides no horses

Down the hill

But comes on foot

A goosegirl still

And all the loveliest

Things there be

Come simply,

So, it seems to me.

Edna St. Vincent Millay

Living spaces may be so arranged and interrelated that common areas may be shared to make each component space seem larger. Apparent spatial size may be increased also by the subtle use of forced perspective and by miniaturization. Again, by the studied arrangement of walls and openings, views can be designed to include attractive features of the site or neighboring properties or extended to the distant hill or horizon. Even within the walled garden or court the ultimate spaciousness can be experienced by the featured viewing of the sky and clouds and the evening constellations. It is no happenstance that in crowded Japan a favorite spot on the garden terrace is that reserved for the viewing of the moon.

The spirit of a garden is its power to charm the heart.

Kanto Shigemori

The earth is our home and the ways of nature our paths to understanding.

Nature Appreciation

Deeply ingrained in all of us is an instinctive feeling for the outdoors—for soil, stone, water, and the living things of the earth. We need to be near them, to observe and to touch them. We need to maintain a close relationship with nature, to dwell amid natural features and surroundings, and to bring nature into our homes and into our lives.

A distinguishing mark of the recent American dwelling is the trend toward indoor-outdoor living. Most interior use areas now have their outdoor extensions—entryway to entrance court, kitchen to service area, dining space to patio, living space to terrace, bedroom to spa, game room to recreation court, and sunroom to garden. In the well-planned habitation, especially in milder climes, it is often difficult to differentiate between indoors and out.

It has been theorized that, ideally, each home and garden should be conceived as the universe in microcosm. If this idea seems abstruse, let it pass. Perhaps in time, upon further reflection, you may find it to have deep meaning.

Present American showcase (vestigial renaissance). Nature ignored. Outward orientation. Privacy is lost. Little use of property. A product of side-yard, setback, and no-fence restrictions.

Future American-trend home. Total use of site as living space. Privacy regained. Indoor-outdoor integration. Natural elements introduced. Compact home-garden units grouped amid open park and recreation areas which preserve natural-landscape features.

Existing Site Features

Often a residential site is selected because of some outstanding attribute. It may be a venerable oak or an aspen grove. It may be a spring, a pond, or a ledge of rock. It may be an outstanding view. All too often those things most admired when the site was acquired are ignored or lost in construction. It only makes sense that such distinctive features be preserved and dramatized in the homestead planning.

Area Allocation

By custom in the United States, and almost uniquely among worldwide homesteads, the area fronting on the passing street has usurped a large part of each residential property for the sole purpose of home display. Traditionally, the foreground of open lawn has been bordered by shrubs, the house garnished with foundation planting for public approbation. Side yards, too, have been treated mostly as unused separation space—leaving only the backyard for family use and enjoyment. It is only recently that the unified house-garden concept has gained popularity and that indoor-outdoor living has come into its own.

The most obvious place to put the house is not always the right one. If there is only a small area of land, you’ll be tempted to use it for the house. It probably should be saved for arrival, parking or garden.…

Is there one particular spot on the property that seems just right in every way? Have you picnicked there and found it idyllic? Have you spent long winter evenings planning a house there? Has it occurred to you that if you build your house there the spot will be gone? Maybe that’s where the garden should be.

Thomas D. Church

Some costly sweeps of irrigated and manicured lawn will long be with us, as will many dollhouse and castle homes designed primarily for display. Increasingly, however, the greenswards are being reduced in size, homes opened up to patios, courtyards, and open recreation space. Most of the natural ground forms and vegetation are being preserved, and family life more outwardly oriented.

The Dwelling

The residence is the centerpiece of the homestead—within which and around which everything happens. What happens depends upon the type of residence selected and the kinds of home life planned for. If there is truth to the saying that in time dog owners come to resemble their canine pets, then it can likewise be observed that much of what homeowners are and do can be judged by their choice of dwellings.

The dwelling itself is a structural framework for living the good, full life. In some cases, the good life may be confined to the walled enclosure of a residence standing proud, aloof, and self-contained. Other homes may open outward, serving as a multifaceted viewing box and staging base for a host of outdoor activities.

Be it an urban apartment, suburban residence, a farm homestead, or wilderness retreat—each has its limitations and possibilities in terms of indoor-outdoor relationships.

In the city high-rise, the outdoor experience may be provided by no more than a sunny window ledge with potted plants or a balcony with seating, a view, and perhaps a hanging basket or two. With good fortune there might even be a private or shared roof garden. An on-grade town house may have its doorstep planting and a rear courtyard with expanded opportunities—as for dining space under a tree or arbor, a pool, a fountain, or patch of herbs or flowers. The suburban home or farmstead, with more area, can open out to a wider array of outdoor living and working spaces. So, too, with the remote cabin or cottage whose owners may choose to leave the natural woodland surrounds unchanged.

Outdoor Activity Spaces

Every outdoor activity needs its measure of usable space. This space may be as small as that required for a child’s sandbox or kitchen herb garden—or as large as for a tennis court, swimming pool, vegetable garden, orchard, or even a putting green. No matter what the anticipated uses, if they are to be realized and enjoyed they must be designed into the plans.

RESIDENTIAL OUTDOOR OPEN SPACE (some possibilities).

Outdoor living areas are designed to:

• Provide useful and pleasant spaces for all activities

• Integrate with and complement the architecture

• Fit into the site in such a way as to preserve and reveal its best features

The patio or terrace, embraced by the dwelling, extends its interior spaces and relates them to all outdoors. The area between home and garage, open or enclosed, may serve as an entrance court or outdoor living room—with paving and planting and perhaps a wall fountain or other water feature.

Outdoor activity space. © D. A. Horchner/Design Workshop

Bordering the patio or terrace may be the game court or lawn, cultivated garden, or natural vegetation. The cultivated garden may be no more than a scattering of selected shrubs, clumps of iris, a swath of crocus and narcissus, a bed of lilies, or patch of native grasses. It may consist of a specimen evergreen or a flowering crab apple in a planter with an edging of myrtle or ivy. It could be no more than a square of tulips within an area of paving or a raised bed of peonies surrounded by gravel mulch. A tubbed fig tree. A cactus garden. Or an extensive outlay of well-tended borders and beds.

A single pot of geraniums on the table is a garden in itself, as is a poolside grouping of containers spilling over with blossoms. Some of the most beautiful garden spaces remembered could be encompassed by the outreach of one’s arms.

The service area—open, walled, or partially screened—is most often associated with the garage and parking court. Here space is to be provided for deliveries, car storage, and turnabout. Here too will be provision for the temporary storage of refuse and recyclable materials waiting for collection and for the compost station.

As an adjunct there may be an offset storage shed for equipment and supplies. It may serve as well to house the meters and valves of utility systems and to hang the hose reels.

The service court border is a convenient location for the kitchen garden and for the entryway to a possible greenhouse, potting shed, or vegetable garden. Here, if there are screen walls, arbor, or fencing, is an opportune place for the growing of flowering vines or grapes or such espaliered fruits as oranges, lemons, pears, figs, peaches, or apples.

Service courts often double as a paved recreation area, with net-post sockets, line markings, and perhaps a basketball backstop. At one side there may be a gated entry to the children’s play space, with swings and play equipment—overseen, if possible, from the adjacent kitchen windows.

The deletion of one or more modular units provides space for post and bench settings, pools, plant bins, plants, etc.

Modular paving units vary widely in size and type.

A modular paving system

• Is flexible

• Helps achieve design unity

• Reduces installation and replacement costs

MODULAR PAVING

Supplementary Structures

As noted, many site-related spaces can be planned into the dwelling or attached thereto by extension. Again, a garage, guesthouse, or studio may be detached and designed as an architectural counterpoint. So, too, with the smaller workshop or toolshed. Supplementary structures may be intentionally varied in character—more related to the site than to the domicile, and suited particularly to the intended use. Such might be poolside dressing rooms or an overlook shelter. Sometimes, living quarters are incorporated in a recreation structure such as a weekend ski lodge or a boathouse with its related slips and dock.

Supplementary structures. Tom Fox, SWA Group; Belt Collins; Barry W. Starke, EDA; Barry W. Starke, EDA

Furnishings

No homestead is complete without its outdoor equipment and furnishings. A well-organized storage wall or shed complete with maintenance machinery and tools is a must.

Recreation supplies and equipment—the nets, paddles, and racquets; the quoits, stakes, and hammock; the archery target and chest of toys—are all to have their ordered place. Then too there will usually be benches, chairs, tables, and other such outdoor equipage. Paving, ground covers, and planting—which may or may not be considered furnishings—are treated in other chapters of this book.

Besides the basics, there may be as well such decorative accouterment as planters, window boxes, and a variety of wooden or ceramic containers. Mosaic murals or panels add interest and color, as do canopies and awnings. Sculpture is always an attribute, as are flags and seasonal decorations for the holidays. Then there are such animating features as wind-bells, birdbaths, and feeders.

Not to be overlooked are the enhancements of water and lighting. Water in some form—brimming basin, rivulet, trickle, spray, or splash—has a place in every garden. Lighting, too. A post light to mark the walk entrance, trace lighting along the drive and paths, floodlighting of the game court, uplighting of trees, and the highlighting of sculpture, mural, floral display, or moving water—all add much of pleasure and sparkle to the evening.

Site furnishings can be built in like this seat wall or freestanding. © D. A. Horchner/Design Workshop

Effective lighting of water feature. Belt Collins

Water, actual or implied, has a place in every garden. Nelson Byrd Woltz Landscape Architects

The cost of exterior furnishings is but a fraction of the overall domicile outlay. Often these outdoor fittings are the things most seen and used and thus most experienced. This is reason enough to acquire and enjoy the best. In large measure, the quality of the homestead is gauged by the quality of the furnishings.

Variations on a Theme

When in our planning we ignore the natural processes or violate the land, we must live with the distressing consequences. When, however, we truly design our structures and living spaces in response to the forces, forms, and features of the host landscape, the lives of the occupants will be infused with a sense of well-being and pleasure.

The accompanying photographic examples have been selected to illustrate the means by which homes and gardens may be planned together, in harmony with their site and landscape environs—and responsive to the needs and desires of the users.