When the settlers beached their rough landing boats on our eastern shores, they brought with them the carefully tended seeds, roots, and cuttings of our first gardens. Our gardens now stretch from sea to sea. For most Americans, the love of plants and gardening is inherent.

Those of us whose work it is to help plan our living environment can learn from this. It is our hope that this feeling for plants and their care may extend to the care of all vegetation and the waters and soil which support it; that the best of our wilderness and wild rivers may yet be preserved; that our vulnerable watersheds may be reforested and protected; that essential marshes may be restored and reflooded; that our remaining dunes may be replanted to bearberry and juniper, to fox grape and pine, or reseeded to their cover of sea oats; that our clustered communities can be planned within and around an all-embracing open-space framework of farmland and forest; and that our homes and schools may be planned as gardens and our cities as garden parks.

Many involved in land planning think of plants as no more than horticultural adjuncts to be arranged around construction projects which are otherwise complete. Nothing could be further from the truth. Vegetation and existing ground cover are in fact one of the primary considerations in the selection and planning of most properties. To a large extent they establish the site character. They hold the soils, modify the climate, provide windbreak and screen, and often define the conformation of use areas.

Plants in the landscape are either those existing in their natural habitat or those which have been introduced. Since established plants by the very fact of their existence have proved themselves to be suited to the site, it would seem logical to preserve them, at least until the need for their removal has been thoughtfully determined. Persons who have had occasion to replace vegetation, often carelessly destroyed, know the problems and costs involved.

When, however, new plantings are prescribed, they are to be given careful consideration, for a single inappropriate plant can alter or destroy the visual quality of a landscape or disrupt its ecological balance.

Conversely, well-conceived plantings can do much to transform an otherwise dull and barren site into a more useful, comfortable, and pleasant place to be.

Slope and watershed protection.

Windscreen.

Overhead space definition and canopy.

Enframement.

Backdrop.

Shade.

Ground space definition.

Plan reinforcement.

Scale induction.

Ornamentation.

Each and every plant installed should serve a predetermined purpose. It is to be selected as the best of the available alternatives to suit the specific growing conditions and the precise design requirements, for planting design of excellence is a blending of science and art.

Base Map

For overall landscape planting, as for a residential site, school ground, or hospital, a base plan at the scale of 1 inch to 10 feet, 20 feet, or 30 feet is recommended, with 1 inch to 40 feet as a maximum. For detailed or limited areas, as for a flower bed or kitchen garden, a scale of 1 inch to 1 or 2 feet may be more workable. The plan should bear the owner’s name and address, graphic scale, date, and a fairly accurate north point. It should also show building outlines, fenestrations, and any such topographical features as walls, fences, lampposts, driveways, walks, or other paved areas, and existing plants to remain.

Plant Selection

With a print of the base map in hand, one is ready for plant listing and allocation. As a start, it is suggested that the first plan be a rough study, with notes, diagrams, and a tentative listing of plant types desired. Even in this first trial listing one should have in mind the characteristics of each plant considered—its shape, height, spread, foliage, color and texture, season of bloom and fruiting, and so forth. Essential, too, is a general knowledge of its cultural requirements, including its hardiness, preferred soil type, acidity range, and moisture content; its tolerance for sun, shade, and exposure; or its need for protection.

Some gardeners have an intuitive feel for such things, but for most the green thumb comes only with years of hands-on experience.

In plant selection, guidebooks and catalogs are useful, but there is no substitute for visits to a nursery or sales lot. A drive round the neighborhood is helpful, too, for it shows what does well and looks best in various locations. Fortunate are those who have gardening friends to whom they may turn for counsel.

Installation

With or without a planting concept in mind, if the initial installation is to be sizable it is usually wise to call upon the services of an experienced professional gardener or landscape architect for a detailed layout. There are then several courses of action. The owner may do the planting at his or her leisure, or it may be installed in one or more phases by a gardener or selected landscape contractor. If the installation is to be let out to bid, as in sizable operations, a complete set of plans, details, specifications, and bidding documents will be needed.

In preparing the planting layout for garden, campus, industrial park, or new community, the approach is much the same. The aim is to enhance in all ways possible the routes of movement and the usable areas of the site. The following time-tested principles are offered as a guide.

Preserve the existing vegetation. Streets, buildings, and areas of use are to be fitted amid the natural growth insofar as practicable. The landscape continuity and scenic quality will thus be assured; the cost of site installation and maintenance will be reduced; and the structures, paved surfaces, and lawns will be richer by contrast.

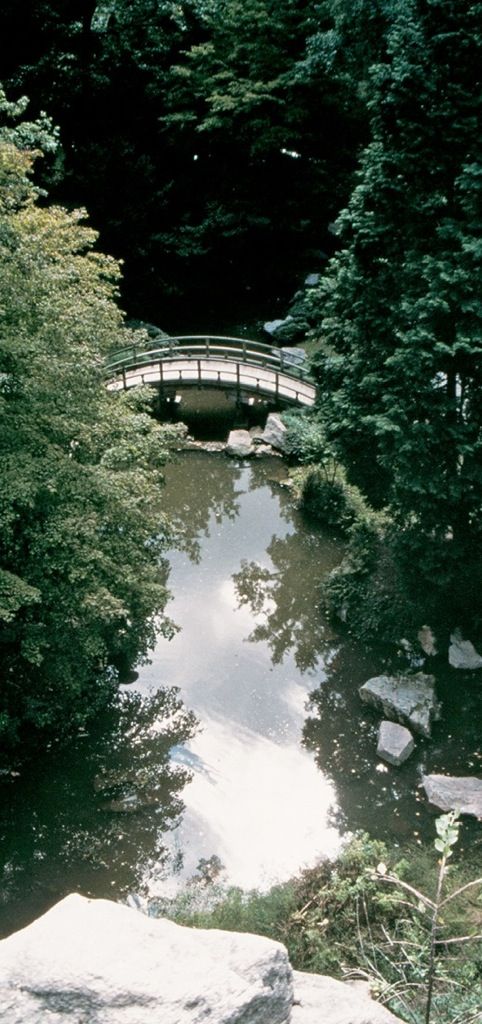

Preserving natural vegetation. Lauren Todd, Stephen Stimson Associates

Trees can define a space or frame a view. Barry W. Starke, EDA; Barry W. Starke, EDA

Select each plant to serve its intended function. Experienced designers first prepare a rough conceptual planting diagram to aid in making detailed plant selections. The diagram is usually in the form of an overlay to the site construction drawings. On it are sketched out, area by area, the outlines, arrows, and notes to describe what the planting is to achieve, as for example:

Light shade here.

Screen unsightly billboard.

Cast tree silhouette on wall.

Reinforce curve of approach drive.

Use ground cover and spring bulbs in foreground.

Plant specimen magnolia against evergreens.

Enframe valley view.

Shield terrace from glare of athletic field lights.

Provide enclosure and windscreen for game court.

The more complete the conceptual diagram and notes, the easier the plant selection, and the better the final results.

Trees are the basics. If tree selection and placement are sound, the site framework is well established. Often, little additional planting will be needed.

Group trees to simulate natural stands. As a rule, regular spacing or geometric patterns are to be avoided. Trees in rows or grids are best reserved for limited urban situations where a civic or monumental character is desired.

Use canopy trees to unify the site. They are the most visible. They provide the dominant neighborhood character and identity. They provide sun filter and shade and soften architectural lines. They provide the spatial roof or ceiling.

Install intermediate trees for understory screening, windbreak, and visual interest. They are the enframers, particularly suited to the subdivision of a larger site into smaller use areas and spaces. As a category they include many of the better accent plants and ornamentals and may be used as individual specimens.

Utilize shrubs for supplementary low-level baffles and screens. They serve as well to provide enclosure, to reinforce pathway alignments and nodes, to accentuate points and features of plan importance, and to furnish floral and foliage display. They can also be used (sparingly) for hedges.

Treat vines as nets and draperies. Various types can be planted to stabilize slopes and dunes, to cool exposed walls, or to provide a cascade of foliage and blossoms over walls and fences.

Install ground covers on the base plane to retain soils and soil moisture, define paths and use areas, and provide turf where required. They are the carpets of the ground plane.

In all extensive tree plantings, select a theme tree, from three to five supporting secondary trees, and a limited palette of supplementary species for special conditions and effects. This procedure helps to assure a planting of simplicity and strength.

Choose as the dominant theme tree a type that is indigenous, moderately fast-growing, and able to thrive with little care. These are planted in groups, swaths, and groves to provide the grand arboreal framework and overall site organization.

Use secondary species to complement the primary planting installation and to define the site spaces of lesser magnitude. Each secondary tree type will be chosen to harmonize with the theme tree and natural landscape character, while imbuing each space with its own special qualities.

Supplementary tree species are used as appropriate to demarcate or differentiate areas of unique landscape quality. The uniqueness may be that of topography, as ridge, hollow, upland, or marsh. It may be that of use, as a local street or court, a quiet garden space, or a bustling urban shopping mall. It may be that of special need, as dense windscreen, light shade, or seasonal color.

Exotic species are to be limited to areas of high refinement. They are best used only in those situations in which they may receive intensive care and will not detract from the natural scene.

Use trees to sheathe the trafficways. An effective design approach is to plant the arterial roads or circulation drives with random groupings of trees selected from the secondary list. Local streets, loop drives, and cul-de-sacs are transitioned in, but each is given its own particular character with supplementary trees (and other plants) best suited to the use, the topography, and the architecture.

Install screen plantings adjacent to trafficways to reduce noise and glare.

The random spacing of trees is suited to the naturalized landscape—as for park and recreation areas and reforestation. Often a blend of indigenous, nursery, and permanent species produces the best stand.

The geometric spacing of canopy trees creates spacious architectural rooms. This is more appropriate in level, geometric courtyards of civic-monumental character.

Trees in a single or double row have strong visual impact. This arrangement is therefore best reserved for the urban or built environment.

In the more natural landscape an offset, irregular tree line is usually preferred.

Give emphasis to trafficway nodes. The intersections of circulation routes are often given added prominence by the use of modulated ground forms, walls, fences, signing, increased levels of lighting, and supplementary planting.

Background. Barry W. Starke, EDA

Shadow. Barry W. Starke, EDA

Silhouette. Barry W. Starke, EDA

Foreground. Barry W. Starke, EDA

Texture. © D. A. Horchner/Design Workshop

Form. Barry W. Starke, EDA

Color. Tom Fox, SWA Group

Line. © D. A. Horchner/Design Workshop

Keep the sight lines clear at roadway intersections. Avoid the use of shrubs and low-branching trees within the sighting zones.

Keep the sight lines clear at trafficway intersections.

Create an attractive roadway portal to each neighborhood and activity center. The entrance planting should be arranged to provide a welcoming harbor quality.

Create a harbor-like entrance portal to each neighborhood.

Arrange the tree groupings to provide views and expansive open spaces. Plants are well used as enframers rather than fillers.

Avoid regular spacing—or the placement of more than two trees in a line. Distances depend upon tree types and whether free-standing specimen or an inter-laced canopy is desired.

Close or compress the plantings where the ground forms or structures impinge. This sequential opening and closing and increasing or decreasing the height, density, and width of the planting along any route of movement give added richness and power to the landscape.

Expand the roadside plantings. Where space is limited, the initial landscape plantings and often site construction may occur outside the right-of-way. A landscape or planting easement may be required.

Use plantings to reinforce the alignment of paths and roadways. They can help to explain the plan layout and give clear direction.

Intermediate trees (and shrubs) are the place, plane, and alignment definers. Use them to reinforce the lines and forms of the plan.

Provide shade and interest along the paths and bikeways. If made attractive, they will be used.

Trees provide shade and interest along walks and bikeways.

Conceal parking, storage, and other service areas. Trees, hedges, or looser shrubs may be used alone or in combination with mounding, walls, or fencing to provide visual control.

Plants combined with mounding can hide parking and service areas.

Consider climate control in all landscape planting. Plants can be used to block winter winds, channel the breeze, temper the heat of the sun, and otherwise improve the microclimate.

Complement the topographical forms. By skillful planting, the visual impact of the landscape can be greatly enhanced.

Use plants as space definers. They are admirably suited to enclose, subdivide, and otherwise articulate the various functional spaces of the site and the passageways that connect them. They convert use areas into use spaces. By their associative nature and their color, texture, and form, they can endow each space with qualities appropriate to the use or uses intended.

Combine planting with earth shaping to create landscape interest.

Landscape construction and planting can occur outside of the street right-of-way (R/W) where space is limited and a “Landscape Easement” provided.

Plants are well used to accentuate land forms and intensify landscape power.

Avoid monotonous edges in roadside and other plantings.

Undulation in both the horizontal alignment and vertical profile add landscape appeal.

In mass plantings emphasize the points with dominant plants and make the bay recede.

Strengthen the building closures and trafficway modes with trees of more structural character.

A similar listing is made for shrubs, vines, and ground covers. Together they should constitute a compatible family of plants expressive of the site character desired.

Plants soften the ground plane. © D. A. Horchner/Design Workshop

Trees create outdoor rooms. PWP Landscape Architecture

Plants used for backdrop, screening, shade, or space definition are generally selected for strength, cleanliness of form, richness of texture, and subtlety of color. Plants to be featured are selected for their sculptural qualities and for ornamental twigging, budding, foliage, flowers, and fruit.

Stress quality, not quantity. One well-selected, well-placed plant can be more effective than 100 plants scattered about at random.

Within the past few years landscape planting at all levels has undergone a remarkable change. This is a direct reflection of several cultural transitions such as:

- A general change in the American lifestyle from the ostentatious to the casual, from the formal to the informal

- Two working-parent families with little spare time for gardening

- Smaller homesites and lack of garden space, especially in urban areas

- A drastic reduction in the number of available caretakers, gardeners, and maintenance personnel

- Depletion of freshwater reserves and limitations to irrigation

All of these trends have led to a reduction in the size of lawn and garden areas. One appealing result has been the expanding practice of container gardening. Instead of cultivated garden beds, the trend is now toward planted containers—ceramic pots, either free standing or in window boxes, raised stone bins, planters, or hanging baskets.

The advantages of container plantings are many:

- They require less time, effort, and expense for installation and upkeep.

- Far less irrigation is needed.

- The floral display can be placed at strategic accent points (e.g., patios, entrances, or pathway intersections).

- Many floral or foliage containers can be taken indoors for table or window display and appreciation.

Container plantings. Mayer/Reed; Miller Company

Once-barren city streets, now tree-lined, have come alive with plants and floral color. There may be fewer plants than in the traditional public gardens, but they are placed where they count.

With less area and time for gardening, the once-familiar vegetable plot in urban areas is now nearly a thing of the past. For one thing, it is hard to surpass or equal the quality of commercially grown vegetables so temptingly displayed in our markets. Also, it is usually hard for the homeowner to find space to plant even a row of lettuce. Containers planted with parsley, thyme, and other herbs are welcome attributes beside the kitchen door.

Xeriscape. Civitas, Inc.; Orange Street Studio

Our lawn areas are also shrinking. Not only has their maintenance become an extravagance and a chore—the use of our diminishing supply of freshwater for irrigation has come into question. Even when the use of treated wastewater for irrigation has been made mandatory, it is predicted that in time the broad sweeps of lawn (an American phenomenon) will become a rarity.

There are three favored alternatives to the mowed lawn. The first is paving or more construction—which is reasonable only if it serves a good purpose. The second is the so-called Xeriscape treatment—using plants that require little if any irrigation. Such plants, ranging from cacti to a wide selection of tough perennials or ornamental grasses, may be supplemented with mulches of gravel, shells, chips, or bark to create remarkably attractive compositions. A third alternative to the mowed lawn is the preserved natural setting, with or without minor modification. In suburban or rural settings with thriving natural growth this is often much to be preferred. It is relatively maintenance-free, and it is less expensive to establish. It “belongs” to the site and is obviously compatible. It provides refreshing coolness in summer and a welcome windbreak in winter.

Native, or indigenous, plants are those growing naturally on the site and historically characteristic of the region.

Naturalized plants are those introduced accidentally or by intent that have accommodated themselves to the growing conditions and become part of the local scene.

Exotic plants are those foreign to the natural site and locality.

In all these ways and more will the landscape plantings of the future differ.

Landscape Plantings in Low-Impact Design

Green Roofs

Although roofs covered partly or completely with living plants, called green roofs, have been around for centuries, the concept has been embraced and expanded as part of the conservation and sustainability movement in design and building today. Even though the design and installation of green roofs offer many structural and watertight integrity challenges, the benefits are many. In addition to benefitting the environment by reducing stormwater runoff, mitigating climate change, converting and absorbing carbon dioxide, and many other effects, rooftop vegetation provides insulation, extends the life of the roof, and reduces energy consumption.

Theoretically, almost any landscape planting that can be installed on a conventional site can be part of a green roof installation; however, most green roofs are limited to relatively shallow soil to reduce the overall weight of the roof, and, therefore, the size of the planting materials used is limited.

Green roofs. Bruce Forster Photography/Mayer/Reed

Because the world’s population is expected to continue to become more and more urbanized, the use of green roofs will no doubt increase as a means of mitigating the environmental effects of higher population density while at the same time allowing for more open space to be preserved.

Bioswales, Bioretention Areas, and Rain Gardens

Since the 1990s, landscape plantings have assumed a much larger role in the practice of stormwater management (SWM). The primary new features in SWM that employ landscape plantings are bioswales, bioretention areas, and rain gardens. All three features are similar in that they use plants to slow the rate of runoff and to filter sediments and pollutants.

Bioswales are used in areas where water is moving across the surface of a site after being collected from, say, a parking lot to a bioretention area or stormwater management pond. The plants in the swale physically slow the flow of the water, which causes sediments to settle out as plant roots absorb pollutants.

Bioretention areas are generally basins that receive and hold runoff. They are designed to hold and slowly release runoff into the groundwater while filtering it in the process. Here, the landscape plantings serve as filters, absorb pollutants, and enhance wildlife habitat.

Rain gardens perform the same function as bioretention areas, but they generally operate on a smaller scale.

Rain garden. Charles Anderson, FASLA