Christo and Jeanne-Claude. The Gates, Central Park, New York City, 1979–2005. Photo: Wolfgang Volz. Copyright Christo and Jeanne-Claude 2005.

Looking back, I feel fortunate to have been in the Harvard Graduate School of Design during the period 1936–1939, in the tumultuous years of “the rebellion.” At the time, I was somewhat puzzled and disappointed at first, for I had come to the school following the bright Beaux Arts star. Its particular brilliance in those times was perhaps like the last blazing of a meteor ending its orbit, for the Beaux Arts system*8 was soon to wane. But blazing or waning, it was gone by the time I arrived there.

Dean Joseph Hudnut, one of the first of the architectural educators to read the signs, soon brought to the school three prophetic and vital spirits, Gropius and Breuer, late of Germany’s Bauhaus, and Martin Wagner, a city planner from Berlin. They came as evangelists, preaching a strong new gospel. To the jaded Beaux Arts student architects, wearied of the hymns in praise of Vignola, beginning to question the very morality of the pilaster applied, and stuffed to their uppers with pagan acanthus leaves, the words of these new professors were both cathartic and tonic. Their vibrant message with its recurring and hypnotic text from Louis Sullivan, “Form follows function,” was strangely compelling. We began to see the glimmer of a beckoning light.

A fervor almost religious in quality seemed to sweep the school. As if cleansing the temple of idols, Dean Hudnut ordered the Hall of Casts cleared of every vestige of the once sacred columns and pediment. The egg-and-dart frieze was carted away. The holy Corinthian capital was relegated to the cobwebs and mold of the basement. We half expected some sign of God’s wrath. But the wrath did not come, and the enlightenment continued. The stodgy Hall of Casts became an exciting exhibit hall.

As the architects sought a new approach to the design of their structures, the landscape architects sought to escape the rigid plan form of the major and minor axis, which diagram, inherited from the Renaissance, had become the hallmark of all polite landscape planning. Inspired by the example of our architectural colleagues, we assiduously sought a new and parallel approach in the field of landscape design.

Through the resources of Harvard’s great library of planning we peered into history. We pored over ancient charts and maps and descriptions. We scanned the classic works of Europe and Asia for guidance. We searched for inspiration in the related fields of painting, sculpture, and even music.

Our motives were good; our direction excellent. But, unknowingly, we had made a fatal error. In searching for a better design approach, we sought only to discover new forms. The immediate result was a weird new variety of plan geometry, a startling collection of novel clichés. We based plan diagrams on the sawtooth and the spiral, on stylized organisms such as the leafstalk, the wheat sheaf, the fern frond, and the overlapping scales of a fish. We sought geometric plan forms in quartz crystals. We adapted “free” plan forms from bacteria cultures magnified to the thousandth power. We sought to borrow and adapt the plan diagrams of ancient Persian courtyards and early Roman forts.

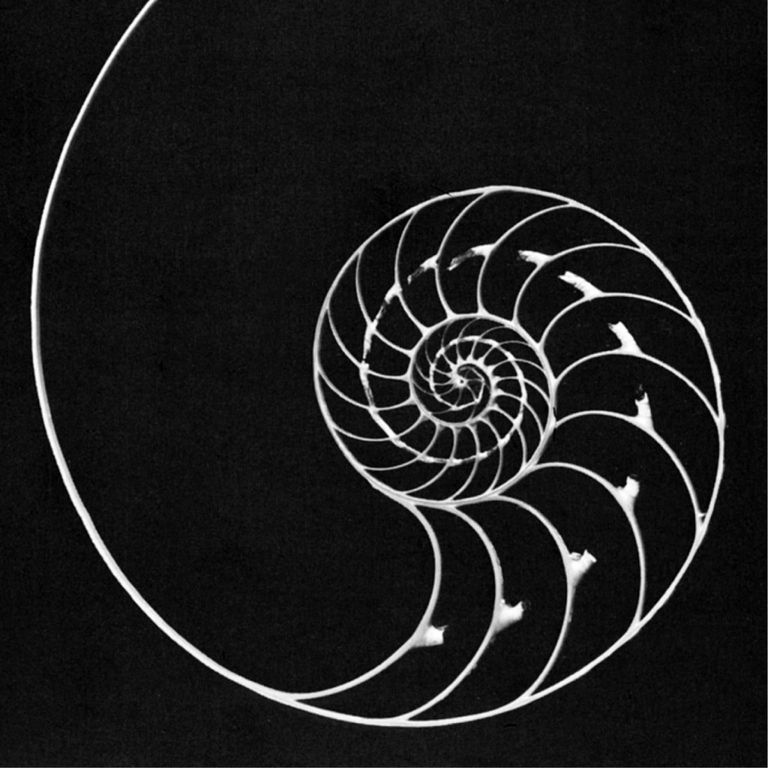

We soon came to realize that new forms in themselves weren’t the answer. A form, we decided wisely, is not the essence of the plan; it is rather the shell or body that takes its shape and substance from the plan function. The nautilus shell, for instance, is, in the abstract, a form of great beauty, but its true intrinsic meaning can be comprehended only in terms of the living nautilus. To adapt the lyric lines of this chambered mollusk to a schematic plan parti came to seem to us as false as the recently highly respectable and generally touted practice of adapting the plan diagram of say, the Villa Medici of Florence to a Long Island country club.

We determined that it was not borrowed forms we must seek, but a creative planning philosophy. From such a philosophy, we reasoned, our plan forms would evolve spontaneously. The quest for a new philosophy is no mean quest. It proved as arduous as had been that for new and more meaningful forms. My particular path of endeavor led in a search through history for timeless planning principles. I would sift out the common denominators of all great landscape planning. At last, I felt sure, I was on the right track.

In retrospect, I believe this particular pilgrimage in search of the landscape architectural holy grail was not without its rewards, for along the way I met such stalwarts as Lenôtre, Humphry Repton, Lao-tzu, Kublai Khan, Pericles, and fiery Queen Hatshepsut. Many of their planning concepts so eagerly rediscovered (some to be set forth in this book) have served, if not as a planning philosophy, at least as a sound and useful guide.

Like good Christians who, in their day-by-day living are confronted with a moral problem and wonder, “What would Christ do if he were here?” I often find myself wondering at some obscure crossroads of planning theory, “What would Repton say to that?” or “Kublai Khan, old master, what would you do with this one?”

But back to our landscape classes and our student revolution. Sure that we had found a better way, we broke with the axis. According to Japanese mythology, when the sacred golden phoenix dies, a young phoenix rises full-blown from its ashes. We had killed the golden phoenix, with some attending ceremony, and confidently expected its young to rise, strong-winged, from the carnage. We had never checked the mythological timing. But we found that, in our own instance, the happening was not immediate.

In lieu of the disavowed symmetry, we turned to asymmetrical diagrams. Our landscape planning in those months became a series of graphic debates. Our professors moved among our drafting tables with wagging heads and stares of incredulity. We had scholarly reasons for each line and form. We battled theory to theory and principle to axiom. But, truth to tell, our projects lacked the sound ring of reality, and we found little satisfaction in the end result of our efforts.

Upon graduation, after seven years’ study in landscape architecture and a year of roaming abroad, and with a hard-earned master’s degree, I seemed to share the tacit feeling of my fellows that while we had learned the working techniques and terms of our trade, the indefinable essence had somehow escaped us. The scope of our profession seemed sometimes as infinite as the best relating of all mankind to nature, sometimes as finite as the shaping of a brass tube to achieve varying spouting effects of water. We still sought the poles to which our profession was oriented. For somehow it seemed basic that we could best do the specific job only if we understood its relationship to the total work we were attempting. We sought a revealing comprehension of our purpose. In short, what were we, as landscape architects, really trying to do?

Like the old lama of Kipling’s Kim, I set out once again to wander in search of fundamentals, this time with a fellow student.*9 Our journey took us through Japan, Korea, China, Burma, Bali, and India and up into Tibet. From harbor to palace to pagoda we explored, always attempting to reduce to planning basics the marvelous things we saw.

In the contemplative attitude of Buddhist monks, we would sit for hours absorbed in the qualities of a simple courtyard space and its relationship to a structure. We studied an infinite variety of treatments of water, wood, metal, plant material, sunlight, shadow, and stone. We analyzed the function and plan of gardens, national forests, and parks. We observed people in their movement through spaces, singly, in small groups, and in crowds. We watched them linger, intermingle, scatter, and congregate. We noted and listed the factors that seemed to impel them to movement or affected the line of their course.

We talked with taper-fingered artists, with blunt-thumbed carpenters, with ring-bedecked princes, and with weathered gardeners whose calloused hands bore the stains and wear of working in the soil. We noted with fascination the relationship of sensitive landscape planning to the arc of the sun, the direction and force of the wind, and topographical modeling. We observed the development of river systems and the relation of riverside planning to the river character, its currents, its forests and clearings, and the varying slopes of its banks. We sketched simple village squares and attempted to reduce to diagram the plan of vast and magnificent cities. We tested each city, street, temple group, and marketplace with a series of searching questions. Why is it good? Where does it fail? What was the planner attempting? Did he achieve it? By what means? What can we learn here? Discovering some masterpiece of planning, we sought the root of its greatness. Discovering its overall order, we sought the basis of order. Noting unity in order, we sought the meaning of unity.

This consuming search for the central theme of all great planning was like that of the old lama in his search for truth. Always we felt its presence to some degree, but it was never clearly revealed. What were these planners really seeking to accomplish? How did they define their task? How did they go about it? Finally, wiser, humbled, but still unsatisfied, we returned to America to establish our small offices and be about our work.

Years later, one warm and bright October afternoon I was leaning comfortably in the smooth crotch of a fallen chestnut tree, hunting gray and fox squirrels, the timeless sport of the dreamer. My outpost commanded a lazy sunlit hollow of white oak and hemlock. The motionless air was soft and lightly fragrant with hay fern. Close by, beyond a clump of dogwood still purple with foliage and laced with scarlet seed pips, I could hear the squirrels searching for acorns in the dry, fallen leaves. An old familiar tingling went through me, a sense of supreme well-being and an indefinable something more.

Ryoanji. Barry W. Starke, EDA

Silver Pavilion. Barry W. Starke, EDA

I half recalled that the same sensation had swept through me years ago, when I first looked across the city of Peking, one dusky evening from the Drum Tower at the North Gate. In Japan it had come again in the gardens of the Katsura Detached Palace, overlooking the quiet water of its pine-clouded pond. And again I recalled this same sensation when I had moved along the wooden-slatted promenade above the courtyard garden of Ryoanji, with its beautifully spaced stone composition in a panel of raked gravel simulating the sea.

Now what could it be, I wondered, that was common to these far-off places and the woodlot where I sat? And all at once it came to me!

The soul-stirring secret of Ryoanji lay not in its plan composition but in what one experienced there. The idyllic charm of the Silver Pavilion was sensed without consciousness of contrived plan forms or shapes. The pleasurable impact of the place lay solely in the responses it evoked. The most exhilarating impacts of magnificent Peking came often in those places where no plan layout was evident.

What must count, then, is not primarily the designed shape, spaces, and forms. What counts is the experience! The fact of this discovery was for me, in a flash, the key to understanding Le Corbusier’s power as a planning theorist. For his ideas, often expressed in a few scrawled lines, dealt not so much with masses or form as with experience creation. Such planning is not adapted from the crystal. It is crystalline. It is not adapted from the organism. It is truly organic. To me, this simple revelation was like staring up a shaft of sunlight into the blinding incandescence of pure truth.

Architecture is again in transition. This time in a knee-jerk reaction to the bombastic excesses of later postmodernism to a time of searching introspection. A turning from buildings conceived principally as design objects to simpler, less pretentious, and more humane structures. From those designed to dominate their sites to those fitted compatibly to ground forms, drainage patterns, vegetation, and the arc of the sun. From showpiece mechanisms to environment-friendly, indoor-outdoor habitations conducive to living the good, full life.

With time, this lesson of insight (perception and deduction) becomes increasingly clear. One plans not places, or spaces, or things; one plans experiences—first, the defined use or experience, then the empathetic design of those forms and qualities conceived to achieve the desired results. The places, spaces, or objects are shaped with the utmost directness to best serve and express the function, to best yield the experience planned.

That was long ago. Now, with more than 50 years of practice and teaching behind me, I look back with widened perspective to the days of the student rebellion, and the subsequent years of search and application. In that time there have been other revolts in the fields of architecture and landscape planning. The first was a counterrevolutionary movement against the stark geometric forms and overutilitarianism of the Bauhaus, Gropius and “Corbu” and their fervent disciples, myself among them.

Landscape art is not to be confused with landscape architecture. In the former context, natural elements such as water, stone, or plant materials are used to create a pictorial design or aesthetic experience.

Landscape architecture differs in that it is the art and science of preserving or creating compatible relationships between people and their activities and the natural worlds about them.

This mellowing phase of the raw post-Bauhaus evolution added a welcome warmth and richness. It produced what many believe to be the finest designs of the century. Not only in architecture, but in the related arts and sciences as well. While the direct fulfilling of need remained a given, and while “styles” and ornamentation were taboo—the hard lines were softened; textures and colors were given full play; and sculptors, weavers, and artists were welcomed back into the fold. Buildings were opened up to the sun, the breeze, and the view. Nature was rediscovered.

In landscape planning the trend veered abruptly away from the formalism of the European Renaissance—to one of respect for topographical form and features. Hillocks, ravines, and wooded slopes were left intact to be admired—as were rock outcroppings, springs, streams, dunes, and tidal estuaries. It seemed a near return to Olmstedian times, with echoes of Thoreau. One could hear Aldo Leopold calling.

Then came postmodernism, the “full flowering” of the revolution. In the name of free expression, it elaborated. It distorted. It fantasized. In its heyday it created some of the most bizarre, flamboyant structures and artifacts yet foisted on the public. True—banks, office buildings, and private homes no longer resembled the Beaux Arts Greek temples, Tudor palaces, or Georgian countinghouses. Nor the sometimes brutal concrete and glass constructions of Bauhaus times. Instead, the postmodern “blossoming” brought on a fantasyland of utter nonfunction. Office towers built in regions of blazing summer heat and winter chill, for example, were conceived as glittering Valhallas—with cooling and heating loads that sank their sponsors financially. No matter, the creations “made a powerful statement.” Too often, however, the only statement was, “Look at me. Look at me. Look at me.”

At every turn in the progressive development of our profession there is need for experimentation and innovation. There is need, too, for a constant infusion of new ideas from the world of art and from artists on the leading edge. It is essential, however, that we differentiate between the timely and welcome contributions of landscape artists and the timeless and far broader mission of the landscape architect.

In the extreme, some landscape architects as well came to violate the natural sites to which, by rights, their projects should have responded. Self-conscious “landscape art” was “designed” for its shock value. Human needs, natural systems, and ecologic factors were blithely ignored and, by some, even ridiculed.

The cycles of design expression, as in the arts, architecture, and landscape architecture.

Some years ago Henry Elder, a brilliant architectural historian, shared with his students his concept of the cyclical nature of design. By a simple looping diagram, with examples, he traced through recent history the periods of creative innovation, the maturing toward the classic ideal, and then the decline into the fanciful and effete. Elder noted that well before the bottoming out there always appear the dissenters who, in revulsion, buck the system in protest and start the next upward loop. In their own rebellious ways they seek a new direction—a fresh start in which design, lean and clean, once again leads the way to expressive and meaningful form.

It may well be time for another revolt, this time with an environmental thrust and an ecological spin. A time when once again “form follows function,” but in which the context of “function” is expanded to include the accommodation of all human needs and aspirations.

Viva la revolution!

One plans not places, spaces, or things; one plans experiences.

Essentially, the best living space, indoors and out, is that best suited to the needs and desires of the users.

By this criterion, a highway is not best designed as a strip of pavement of given section, alignment, and grade. A highway is properly conceived as an experience of movement. The successful highway is planned, in this light, to provide for the user a pleasant and convenient passage from point to point through well-modulated spaces with a maximum of satisfaction and a minimum of friction. Many of the serious failures of American roadways stem from the astounding fact that, in their planning, the actual experience of their use was never even considered.

One plans not places, or spaces, or things.… one plans experiences. Tom Fox, SWA Group; PWP Landscape Architecture

To understand life, and to conceive form to express this life, is the great art.… And I have learned to know that in order to understand both art and life one must go down to the source of all things: to nature.…

Nature’s laws—the laws of “beauty,” if you will—are fundamental, and cannot be shaken by mere esthetic conceitedness. These laws might not always be consciously apprehended, but subconsciously one is always under their influence.…

The more we study nature’s form-world, the more clearly it becomes evident how rich in inventiveness, nuances, and shiftings nature’s form-language is. And the more deeply we learn to realize, in nature’s realm, expressiveness is “basic.”

Eliel Saarinen

The best community, by this test, is that which provides for its habitants the best experience of living. A garden, by this standard, is not designed as an exercise in geometry; it is not a self-conscious construction of globes, cubes, prisms, and planes within which are contained the garden elements. In such a geometric framework the essential qualities of stone, water, and plant materials are usually lost. Their primary relationship is not to the observer but to the geometry of the plan. Final plan forms may be, in some rare cases, severely geometric, but to have validity, a form must be derived from a planned experience rather than the experience from the preconceived form.

A garden, perhaps the highest, most difficult art form, is best conceived as a series of planned relationships of human to human, human to structure, and human to some facet or facets of nature, such as the lichen-encrusted tree bole of an ancient ginkgo tree, a sprightly sun-flecked magnolia clump, a trickle of water, a foaming cascade, a pool, a collection of rare tree peonies, or a New Hampshire upland meadow view.

A city, also, is best conceived as an environment in which human life patterns may be ideally related to natural or constructed elements. The most pleasurable aspects of cities throughout history have not derived from their plan geometry. Rather, they have resulted from the essential fact that, in their planning and growth, the life functions and aspirations of the citizens were considered, accommodated, and expressed.

To the Athenian, Athens was infinitely more than a pattern of streets and structures. To the Athenian, Athens was first of all a glorious way of life. What was true of Athens should be no less true of our “enlightened” urban planning of today.

The design approach then is not essentially a search for form, not primarily an application of principles. The true design approach stems from the realization that a plan has meaning only to people for whom it is planned, and only to the degree to which it brings facility, accommodation, and delight to their senses. It is a creation of optimum relationships resulting in a total experience.

We make much of this matter of relationships. What then is an optimum relationship between a person and a given thing? It is one that reveals the highest inherent qualities of that which is perceived.

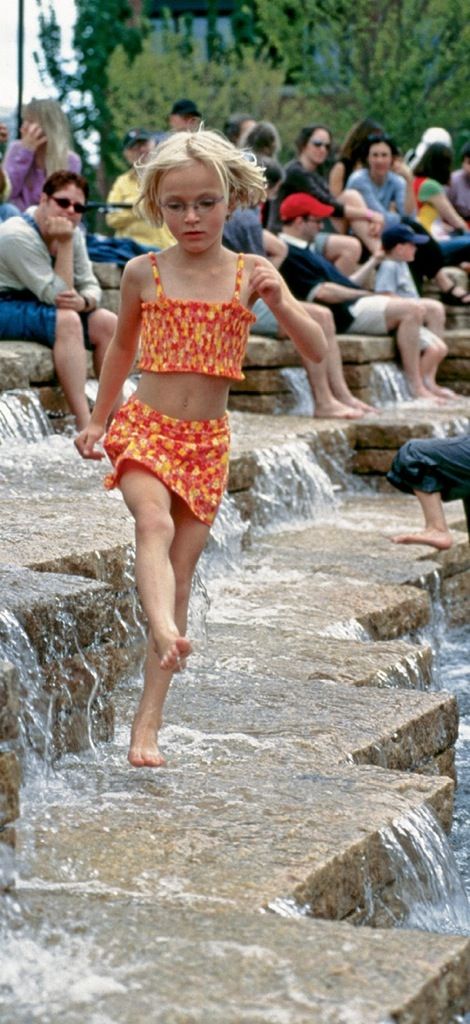

Unplanned experience. Bill Wenk, FASLA, Wenk Associates

In the final analysis, in even the most highly developed areas or details one can never plan or control the transient nuances, the happy accidents, the minute variables of anything experienced; for most things sensed are unpredictable and often hold their very interest and value in this quality of unpredictability. In watching, for instance, an open fire, one senses the licking flame, the glowing coal, the evanescent ash, the spewing gas, the writhing smoke, the soft splutterings, the sharp crackle, and the dancing lights and shadows. One cannot control these innumerable perceptions that, in their composite, produce the total experience. One can only, for a given circumstance or for a given function, plan a pattern of harmonious relationships, the optimum framework, the maximum opportunity.

For to live, wholly to live, is the manifest consummation of existence.

Louis H. Sullivan

The perception of relationships produces an experience. If the relationships are unpleasant, the experience is unpleasant. If the relationships sensed are those of fitness, convenience, and order, the experience is one of pleasure, and the degree of pleasure is dependent on the degree of fitness, convenience, and order.

Fitness implies the use of the right material, the right shape, the right size, and the right volumetric enframement. Convenience implies facility of movement, lack of friction, comfort, safety, and reward. Order implies a logical sequence and a rational arrangement of the parts.

The perception of harmonious relationships, we learn, produces an experience of pleasure. It also produces an experience of beauty. What is this elusive and magical quality called beauty? By reasoning, it becomes evident that beauty is not in itself a thing primarily planned for. Beauty is a result. It is a phenomenon that occurs at a given moment or place when, and only when, all relationships are perceived to be harmonious. If this is so, then beauty as well as usefulness should be the end result of design.

All planning of and within the landscape should seek the optimum relationship between people and their living environment and thus, per se, the creation of a paradise on earth. Doubtless this will never be fully accomplished. Humans are, sadly, too human. Moreover, because the very nature of nature is change, such planning would be continuing, without possible completion, without end. And so it must be. But we may learn from history that the completion is not the ultimate goal. The goal for all physical planners is an enlightened planning approach. Again, for instruction on this point, we may turn to the wisdom of the East. Because of the dynamic nature of their philosophies, the Zen and Taoist conceptions of perfection lay more stress upon the process through which perfection is sought than upon perfection itself. The Zen and Taoist art of life lies in a constant and studied readjustment to nature and one’s surroundings, the art of self-realization, the art of “being in the world.”

Plan not in terms of meaningless pattern or cold form. Plan, rather, a human experience. The living, pulsing, vital experience, if conceived as a diagram of harmonious relationships, will develop its own expressive forms. And the forms evolved will be as organic as the shell of the nautilus; and perhaps, if the plan is successful, it may be as beautiful.

What, again, is the work of the landscape architect?

It is believed that the lifetime goal and work of the landscape architect is to help bring people, the things they build, their communities, their cities—and thus their lives—into harmony with the living Earth.

Nautilus. H. Landshoff