CHAPTER 14

ON APRIL 27, 1945, TEEN PALM HAD BEEN COMMANDER OF his unit for less than twenty-four hours when he was summoned to an unusual meeting of platoon commanders and other officers. More than a dozen men, haggard and unshaven, gathered in the late afternoon.

Two days earlier, an American airman had arrived from Munich, accompanied by a German soldier. The American brought a strange and almost unbelievable request. Please, he asked, do not bomb Munich for the next forty-eight hours.

Who was this man? And why would an American want to halt the bombing of Munich? His name was Bernard McNamara, and nearly two years earlier, at 11:00 a.m. on October 20, 1943, he was riding in one of nineteen American B-17 bombers that roared to life and rumbled down the runway of the Molesworth, England, air base and soared into the sky. The Flying Fortresses each carried ten five-hundred-pound bombs and were headed for Duren, Germany, to drop their payload on the center of the city.

The base was the home of the 303rd Bombardment Group, an Eighth Air Force B-17 bomber group that had been launching bombing missions since 1942. This was the 303rd‘s seventy-ninth mission.

Strapped in the navigator’s seat of the bomber, twenty-four-year-old Second Lieutenant McNamara was calm as the plane rose above the English Channel. This was the twenty-fourth mission he had flown with the pilot, John W. Hendry Jr., and each time they had returned safely to their base. It was his twenty-fifth mission overall — and completing it meant he would qualify to return home. This mission, though, would be his last.

As the nineteen-plane formation crossed the French coast, as many as a dozen Luftwaffe Messerschmitt fighter planes ambushed them, bursting out of a bank of clouds about five hundred yards from the lead B-17. The Messerschmitts zoomed in with cannons blazing and hit McNamara’s plane in the left wing.

Flames erupted and Hendry quickly assessed the problem — the plane was loaded with fuel and a catastrophic explosion was likely just moments away. Indeed, he could see another of the group’s planes spinning in flames as it hurtled toward the ground.

Hendry was able to put the plane in a controlled descent and gave the order to bail out. One by one, eight members of the ten-man crew leaped from the burning craft and popped open their parachutes. They were not safe yet — they were over German-controlled territory.

As McNamara drifted down, suspended from his chute, a German plane swooped toward him, machine guns firing. McNamara was hit in the head — the bullet pierced his face below his right eye and exited under his chin. He also was struck in his left arm and left thigh. He crashed into the roof of an auto repair shop in Sauve, a suburb of Valenciennes, France. Local residents hauled him down and took him to a nearby home.

They put him on the floor near a fire to keep him warm. A doctor was summoned and began patching his wounds.

Two hours later, though, German troops on patrol — drawn to the home by a crowd of French residents that had gathered to see an American — found him and took him prisoner.

Two of the crew did not get out of the plane and were still on board when it crashed. Second Lieutenant William B. Harper and Technical Sergeant James J. Brown were found dead in the wreckage. The other members of the crew — Hendry, Second Lieutenant Richard E. Webster, Technical Sergeant Alfred J. Hargrave, Sergeant Delbert E. Guhr, Staff Sergeant Wilmer G. Raesley, Technical Sergeant Loran C. Biddle, and Staff Sergeant John Doherty — managed to reach the ground alive. All were captured by German troops.

McNamara was taken to a Luftwaffe hospital for further treatment. Three months later, when he was able to walk, he was transferred to Stalag Luft III South, a prison compound in Poland where other Allied airmen were held prisoner.

In March 1944, seventy-six British flyers fled the camp through a tunnel in a break that was famously depicted in the book and film The Great Escape. All but three were captured within two days, some of them as they waited for a train headed toward Alsace, France, and, they hoped, freedom. Returned to the camp, fifty of the seventy-three were executed.

In April 1945, McNamara was among a number of other prisoners who managed to escape from the prison with the assistance of a German soldier in the camp who accepted a bribe of cigarettes to allow McNamara to walk out of the camp and ride off on a bicycle that had been stashed nearby. Following a hand-drawn map, McNamara rode to a nearby farm, where he connected with a group of Serbians who were actively attempting to get an American to Munich to help Gerngross communicate with the Allies about his planned uprising.

From there, McNamara was driven variously by car and truck toward Munich, traveling twenty to thirty kilometers at a stretch. On the night of April 21, McNamara slept in a trailer full of straw, and on the following morning he hid in a water main until a car arrived from Munich. Then he was driven to the home of mechanic George Roedter. By day, Roedter worked on German Army vehicles. Secretly, though, he was a member of Gerngross’s FAB. For many months, Roedter had allowed his home to be used as a hiding place for escaped prisoners of war as they made their way back to the protection of the Allies. Many of these escapees had been helped by Gerngross’s interpreter unit.

As the Allies approached Munich, Gerngross decided that the only credible emissary he could send to reveal his planned uprising, and to ask that the bombing of Munich be halted was an American.

So he went to see George Roedter.

There, Gerngross found McNamara and Sidney Leigh, a twenty-four-year-old lieutenant from New Jersey, whose bomber had been shot down in July 1943 over Kassel, Germany. Like McNamara, he had been taken prisoner by the Nazis. Shuffled from one prison camp to another, Leigh wound up in Stalag VII A, north of Moosburg in Bavaria, Germany. Like McNamara, he escaped, made his way to Munich, and was taken by German resistance members to Roedter’s home.

Gerngross outlined his plan for the revolt and asked Leigh to help the FAB kidnap Franz von Epp, a seventy-six-year-old man of considerable power and influence in the Nazi Party. Gerngross believed that the chance of a successful revolt would increase if he could persuade von Epp to make a public plea urging German soldiers to put down their arms.

When Gerngross proposed that FAB supporters smuggle an American dressed in a German Army uniform to the Allies so they could be alerted, Leigh suggested McNamara, who was asleep in a rear bedroom.

Roedter awakened McNamara and together they walked into the room where Gerngross waited.

“This is First Lieutenant McNamara,” Roedter said.

Speaking in English, Gerngross addressed McNamara, who was still not fully awake.

“I want to send you on a secret mission across the front to your people,” he said. “Do you understand?”

McNamara became alert. He did not hesitate.

“Let’s go,” he replied.

Gerngross explained that McNamara would travel with a French agent and a German from Gerngross’s interpreter unit. If stopped by Germans, the German would say he was transporting two Allied prisoners. If they were able to reach the Allies, they were to explain that they were transporting a German prisoner of war.

Gerngross told McNamara that he was to tell the Allies about the planned uprising and that all bombing of Munich should halt so the revolt could begin. After Munich was in the hands of the FAB, Gerngross said, the city would be handed over to the Allies.

Two hours later, McNamara, who was armed with a pistol, departed with the German soldier and the Frenchman, traveling in a small truck carrying three bicycles. Taking back roads, wagon paths, and other obscure byways, they traveled about thirty-five miles north of Munich where they abandoned the truck and struck out on the bicycles.

They traveled through fields and woods to avoid areas still controlled by the German Army. Occasionally they were close enough to roads to see a steady stream of troops falling back in disarray.

They arrived in Neuberg in the early morning hours of April 25 and were taken to a home controlled by the German resistance, where they ate and went to bed. Massive explosions from dropping bombs roused them several hours later. A plane in flames crashed into the building, and a bomb exploded on the street out in front.

With an escort from the resistance, McNamara and his two companions fled the building, running through burning debris on the street to reach a wall that provided protection as they made their way to a bridge. In the chaos of the bombing, they were able to make their way over the bridge without being noticed. They were taken to a German prisoner-of-war camp where a soldier who was sympathetic to the Allies smuggled them inside.

There they remained to wait for the Allies to approach.

They did not have to wait long. Soon, McNamara began hearing the sound of artillery fire. The Allied attack on Neuberg had begun and in a matter of a few hours the city was overrun. Shortly before midnight, McNamara was escorted to the Allies and delivered Gerngross’s message.

He reported that Gerngross wanted the Allies to halt all Munich bombing raids for forty-eight hours so the FAB could launch its uprising. McNamara explained that Gerngross believed air attacks would bring German soldiers out in force to clean up the rubble, remove the dead, and treat the wounded, and that for the revolt to succeed, the German Army needed to be caught off guard.

McNamara said Gerngross wanted a signal that the Allies had gotten the message.

In Munich, on the evening of April 26, Leigh began seeing flashes in the night sky that could only be artillery fire — the Allies were approaching.

The following night, at midnight, Gerngross went to Roedter’s home, accompanied by Fritz Seiling, von Epp’s chief aide who had secretly defected to the FAB. They came to get Leigh to kidnap von Epp.

A few hours earlier, a bomb called a “Christmas Tree” — used to help bombers locate their targets — had been detonated in the skies over the nearby town of Freising. Gerngross witnessed the fiery explosion. He rightly believed this was the sign that the Allies had been informed and had agreed to suspend bombing the city so the FAB revolt could begin.

When he stepped into Roedter’s home, Gerngross cut a striking figure. Two submachine guns were strapped across his back. Two pistols were jammed into ammunition belts around his waist. In one hand, he carried a sack of grenades.

Speaking rapidly, he explained to Leigh that he was heading to von Epp’s home and wanted Leigh to come along. Gerngross reasoned that von Epp, confronted by an American, would capitulate because he would be convinced that the Nazi cause was doomed.

Leigh agreed, and all three climbed into a waiting car and sped to von Epp’s residence. When they arrived, Leigh remained in the car, clutching the bag of hand grenades.

After a short time, Gerngross returned to the car accompanied by von Epp, who climbed into the front seat. They sped off to the private home of an FAB sympathizer outside of Munich where von Epp was put in a separate room.

Gerngross departed and headed for the radio station in Freimann where he joined twenty FAB commandos armed with submachine guns and other firearms. They overpowered the guards at the radio station and commandeered the microphone. At 2:00 a.m., Gerngross began broadcasting the code word “Fasanenjagd.” The hunt for the golden pheasants was on.

Teams of FAB members donned their armbands and fanned out in search of specific targets. Five teams set out to find Geisler and kill him. The mission to kill Nazis kicked into gear.

One team invaded the Munich police station and disarmed the police there. Other teams attacked and seized the offices of two newspapers.

FAB member Max Stangl later told Stars and Stripes that even before the broadcast began, the Nazi chief of security was walking out of the Ministry of Interior building when three FAB members approached. They asked for his pistol and demanded he sign a resignation letter that Gerngross prepared earlier. After he complied, the men hanged him from a lamppost.

Stangl’s assignment was to kill the editor of the Nazi Party newspaper. He went to the man’s home wearing a militaryhospital sling as if he had been wounded. When he saw the editor come out of his home, Stangl began to feign a limp and started groaning as if in pain.

The man approached and flashed a light on him, demanding to know what was going on. Stangl, who had a pistol in his hand covered up by the sling, shot him three times. When the man fell to the ground, Stangl stood over him and shot him between the eyes for good measure.

At the radio station, Gerngross was broadcasting a lengthy list of entreaties to the city’s civilians, politicians, and factory workers as well as municipal employees in charge of transportation and utilities.

Gerngross revealed the existence of the FAB and said the group was putting an end to Nazism in Munich and that the war was over.

“All opponents of National Socialism [Nazis] are summoned to act together and do your part for the common battle and finish off the rest of the Nazis with a death blow. We are fighting against the madness of battle and for the restoration of peace and a democratic system of government.”

Government officials, he said, must join in to end the war. “The pompous Nazis have forfeited your rights as a state employee. They are only willing to save their own lives and are willing to sacrifice the whole nation — your wives, your children, as well as the soldiers at the front. Strike the death machine of the Nazis with a death blow,” he boomed. “Stay away from your government offices and bring down the machine. Be ready to quickly restore the peace.”

Gerngross pleaded with the utility workers to protect their facilities from destruction by the Nazis. “Take over the security of the water and electrical supply. Watch the activity of Nazis known to you and arrest them when they seem to be suspiciously hanging around the facilities. By acting fast, you can save the lives of thousands of people.”

He urged the transportation and factory workers to stay home. “Don’t go to work. Disrupt transportation when and wherever you can, but be ready to return to normal operation for Freedom Action Bavaria. Do not allow sabotage.”

His voice ringing out over the airwaves, Gerngross told the city police to work for the return of order. “You have seen with your eyes the methods of the Party; the consequences of force without boundaries. You also witnessed the ultimate consequences of this brutal power — how the entire German people stand despised all over the world because they forgot themselves and handed themselves over to bloodthirsty tyrants. Give up your work for the Nazis!”

He urged those listening to hang out white flags of surrender, and, sure enough, flags began to appear from windows across the city. Citizens began streaming into the streets, believing the war had come to an end.

A messenger brought news that Allied troops had broken through at Odelzhausen, a small town about thirty miles northwest of Munich noted for a seven-hundred-year-old castle. Gerngross promptly put it on the air.

“The tower of the castle has been hit by Allied grenades and is ablaze!” he thundered. “The Allies are approaching!”

Advancing Allied troops and Radio Luxembourg heard Gerngross’s appeal. Stars and Stripes printed the headline: “Anti-Nazi Revolt Reported Raging in Munich.”

One of the FAB commando teams targeted Giesler and attempted to storm the building where he was hiding. But they fled when confronted by a barrage of hand grenades. Giesler was quickly spirited out of Munich. Three of his brothers were not so fortunate. They all were killed.

In just a few hours, more than a dozen high-ranking Nazis — golden pheasants — were rousted and assassinated. White flags dangled from the building windows. Citizens flocked to the streets, crying, “The war is over!” Rumors circulated that Hitler was dead.

Emboldened by the broadcast, residents of small towns took up arms against the Nazis as well. In Penzberg, about thirty miles south of Munich, Hans Rummer, who had been the town’s mayor until he was deposed by the Nazis, gathered men and armed them with handguns. They visited nearby mines and persuaded the pit managers to stop working. They visited a local POW camp and promised imminent liberation, then went to the town’s City Hall.

They stormed the building and took over the offices. When the man installed as the mayor by the Nazis came to work, Rummer had him escorted from the building with orders that he leave the city.

Meanwhile, FAB members were working on von Epp, trying to persuade him to go to the radio station and announce the surrender of Munich to the Allies. About 8:00 a.m., Seiling, von Epp’s aide, emerged alone from the room and hustled Leigh out of the house to a waiting car. He explained to Leigh that after hours of cajoling, von Epp had seemed to be on the verge of supporting the revolt, but in the end, he stiffened and refused to cooperate.

“Get on the floor,” Seiling demanded and tromped on the gas pedal. As they sped off, the aide reached over, turned on the radio, and tuned it to a station in a Munich suburb. Leigh heard a voice shouting and ranting. He knew enough German to understand what was being said.

A man was excoriating Gerngross as a traitor and announcing that the rebels had been defeated — the revolt was over. Gerngross, the voice declared, was to be shot on sight. The voice called on the citizens of Munich to remain loyal to the Fatherland and promised that Gerngross and his supporters would be rounded up and executed.

The voice was that of Paul Giesler.

When word reached Gerngross that Giesler had escaped and that the Allies were not going to reach Munich in time to help his efforts, he and some of his top aides fled the city in a car bearing SS license plates. The radio station was soon back in Nazi control.

German soldiers and members of the Werewolves commandos were soon on the streets, where gun battles raged. As many as one hundred fifty FAB insurgents from Munich and surrounding towns were killed in firefights or captured and then executed. Some were hanged on the street. Others were shot in the woods.

In Penzberg, the Werewolves moved in, disarmed Rummer and his men, and put them under guard. Later that day, on orders from Giesler, Rummer and six others were lined up before a wall and executed by a firing squad. That evening, eight more of Rummer’s supporters were arrested and hanged.

In Götting, a Roman Catholic priest named Joseph Grimm was executed. Grimm’s crime? After hearing Gerngross on the radio, he removed a Swastika flag from his church and replaced it with a white and blue Bavarian flag.

In the town of Dachau, street fighting broke out between those who heeded Gerngross’s appeal and members of the SS. A number of the resistance fighters were slain.

Fritz Seiling, von Epp’s aide who had helped in the kidnapping of von Epp, was also executed.

The revolt was over.

Although quashed in a matter of hours, the uprising had inflicted serious damage. The FAB had executed several powerful Nazi leaders and driven Giesler into hiding. The morale of German troops teetered in the face of evidence that defeating Allied forces was an illusion.

Though routed and suffering severe casualties, the FAB did not disappear. Those members who did not flee the city merely hid their armbands and went back to their homes. Some of them were about to meet Teen Palm.

Teen Palm in 1943

Pastor Charles J. Woodbridge’s family in Salisbury, North Carolina, 1945,

from top left:Charles, Ruth, Rosemary, Norma. Bottom left: Pat, John.

Independent Presbyterian Church,

Savannah, Georgia, late 1940s

Ruth Woodbridge, Teen Palm, and Charles Woodbridge

at Columbia Bible College, 1943

Charles and Ruth Woodbridge, 1960

The Grand Parade of Adolf Hitler’s Wehrmacht

fiftieth birthday on April 20, 1939

Capt. William J. Robertson — Commander, Company B, 179th Infantry,

Spring, 1945, in Germany

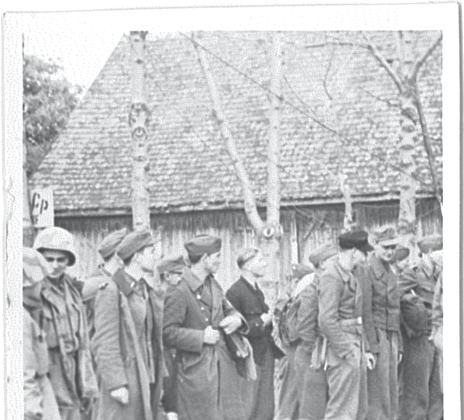

Prisoners, May 1945

Polish boy liberated from prison camp in Nuremburg. He had been imprisioned

at age twelve and freed at age seventeen. He was a bag of bones when found, but after a few months (seen here) seemed well fed.

Letter: Nov. 10, 1944, from Teen to his sister Gladys

Teen on April 24, 1945, just before his regiment

marched on a small series of towns along the Danube River

Teen on left, taken at Bad Ort, Germany, just after the town was captured

Rupprecht Gerngross speaking into the microphone

that he and his troops seized from Nazi leadership

April 29, 1945, Allied Sherman tanks move into Munich, Germany, World War II

Ruins of the Reichstag in Berlin, with Soviet airplanes flying in formation above, May 1945

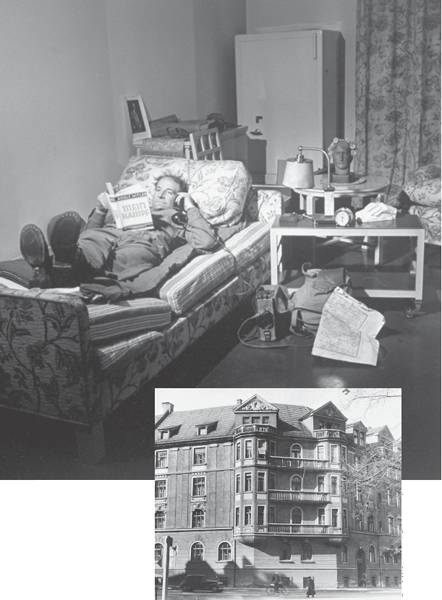

American Sgt. Arthur E. Peters reading Mein Kampf while lounging on a bed that belonged to Adolf Hitler

Hitler’s private residence in Munich, where Teen found the pistol

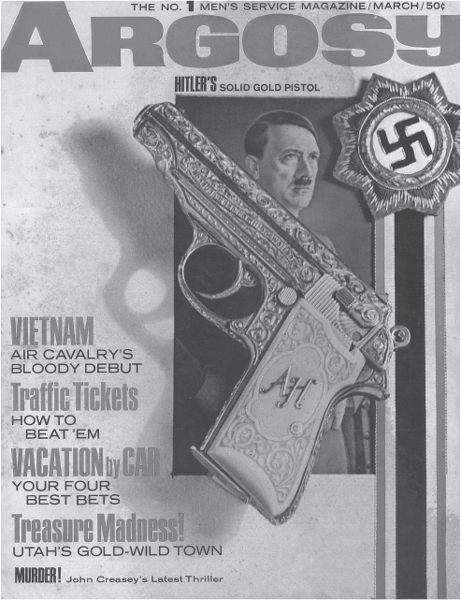

Magazine cover, March 1966

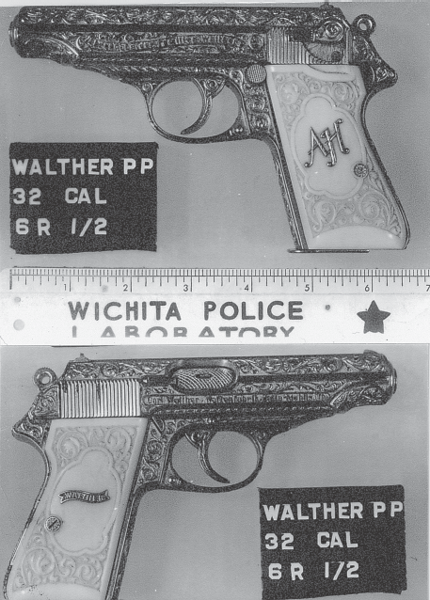

Wichita police photo of gun

Western Union telegram,

May 11, 1945

Helen and Teen Palm, 1943

Lt. Col. Ira A. Palm (Teen) in the late 1950s while stationed at the Pentagon

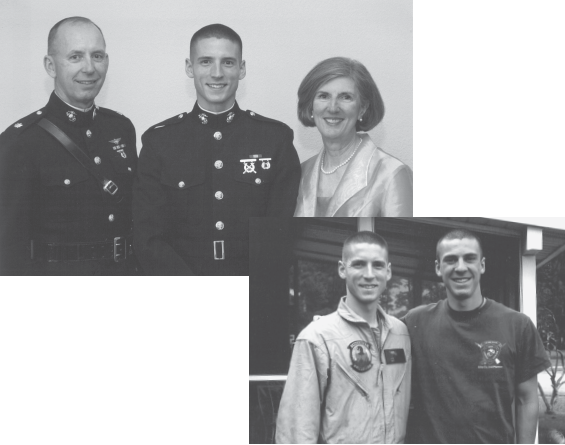

June 17, 2006, Joshua’s wedding. Left to right Jonathan, Joshua, Susie.

April 2008, Joshua and Daniel at Marine Corps Air Station, New River, NC

At Daniel’s OCS graduation, Quantico, VA, July 3, 2010, Joshua, Daniel, and Jonathan