MY thoughts run faster than my pen as I write this, for today I learned that our lives are about to change — we are to sail to Egypt on a galley that leaves the day after tomorrow!

We must make this sudden journey because my father has learned that a warehouse he owns in Egypt has burned to the ground. He must travel there immediately to see it rebuilt. Mother, my brother, Apollo, and I will all travel with him to make our home in Alexandria for two years at least.

It is a thrilling and wonderful idea, for I have never left our Greek island before. We have a fine, big house here on Mytilini, but in Egypt we will have an even bigger one. Everything else will be different, too. This is why I have begun a diary, so that I might write down all that we do each day and record everything new while it is still fresh.

To help in this project, my mother has given me a writing set: a bundle of fine goose quills tied with a purple ribbon, a knife to sharpen them with, a traveling ink pot, and a roll of the finest papyrus I have ever seen. Its surface is as smooth as the skin on Apollo’s back.

In just two days, we shall board our ship in the harbor here and set sail from Mytilini across the warm Aegean Sea. I think I shall like to stand at the front, let down my hair, and feel the salt wind comb and curl it! In little more than a week, we shall be in Alexandria. I cannot wait for this adventure to begin. . . .

FIRST DAY OF OUR VOYAGE

This morning before dawn, we came aboard our ship. As the sun rose, the crew put out their oars and began to beat a splashing tune on the water. From land, I have often watched boats leaving the harbor: they seem to glide gracefully over the blue sea. From the deck, the view is different: a hundred men or more must strain every muscle to push the boat forward.

This morning, though, the crew did not labor for long. The wind blew from the land, and once a sail was raised, they could rest. I stood at the front of the ship with Apollo to let the wind comb my hair, as I had dreamed. Instead it teased it into a knotted mass, which took an hour to untangle!

FIFTH DAY

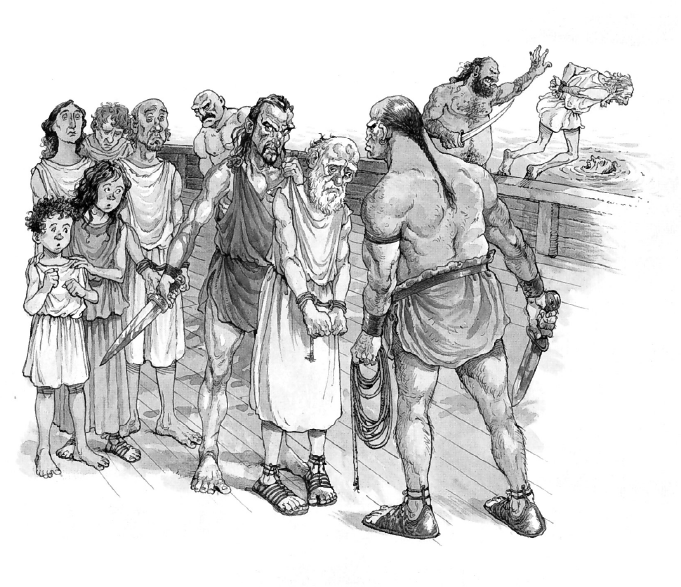

Pity us! Apollo and I have lost everything we loved and cherished. Now we are orphans and slaves, to be bought and sold like goats.

We were but half a day from Rhodes when a sail appeared behind us. From the shape of the ship and the way it cut through the water, the crew could tell that it was a pirate craft. Our mariners rushed to their oars, but though they strained and pulled, the dark outline grew ever bigger behind us.

In the battle that followed, my mother drowned and my father was run through with a pirate sword. My tears flowed, but I could do nothing.

The pirates were not interested in the ship’s cargo of wine but only in taking slaves, which they called “self-loading cargo.” They took from Apollo and me all we possessed except my ink, pens, and papyrus. These they let me keep because they think I will fetch a better price if it is obvious that I know my letters.

Our journey to Egypt is at an end. Now we have begun another journey, to the very center of the world: Rome.

MY THIRD DAY IN ROME

We reached this strange and enormous city two days ago — not directly, but by hopping like frogs, for we were bought and sold three times on the way.

At each auction, Apollo and I clung to each other, in case we should be sold apart, but — praise be to Zeus — it has not happened. Instead, children have joined our miserable band. At each auction, our price rises (though mine more than Apollo’s, for I can speak fluent Latin and read a few words, but he struggles to write even in Greek). Finally we came into the port of Ostia on a stinking barge, which I think must have carried rotten fish before us.

We were herded quickly through the streets to some dark, cramped lodgings. We had food to eat — bread, oil, and olives — but we were all filthy from our long journey. Creatures moved in my hair; my clothes were like rags, and my eyes were red from crying.

Today two women came to the room in which we were locked with the other children. They took us out and gave us water and oil to wash with. Then they cleaned our hair with fine-toothed combs to remove the lice and gave us new garments to wear. I could not help but enjoy this, until one of my companions snapped, “Idiot! Can’t you see that they are preparing us for sale again?”

MY FOURTH DAY

The women returned this morning. They hung wooden signs around each of our necks. I was quite pleased that I could read the Latin words on mine: “Greek maiden.” They also dusted our feet with chalk. This, I learned, was to show that we were newly taken as slaves, and so likely to be a troublesome buy.

“Greeks for sale!” the traders shouted as they pushed Apollo and I onto a little platform so that everyone in the crowd could see us clearly.

The bidding was brisk, and we were sold to a tall man who bought no other slaves in the sale. As he pressed through the crowd toward us, I was relieved that Apollo and I had been bought as a single lot — but, anxious about what would become of us, I asked the man where we were going. He cocked his head and raised his eyebrows, as if he couldn’t have been more surprised to hear a dog speak Latin.

“You’re the property of Gaius Martius,” he replied. “He’s a senator, and I’m his overseer. You’ll work in his domus here in Rome.” He turned Apollo’s right hand over to look at the palm. “Judging by the smoothness of his hands,” he said, “your brother has never done a stroke of work, but he’ll be useful on my master’s farm in the hills.” Then he pushed us forward into the square. “Come on. Shake that chalk off your feet!”

MY SIXTH DAY

My parting from Apollo came sooner than I had dreamed possible, for, seeing me sob all the way from the auction, the overseer clearly decided he’d have no peace until we were separated.

When we reached the house, he pushed me into a little room and bolted the door. I hammered with my fists but simply got bruised and splintered. I lay on the bed and tried to forget I was a prisoner by writing everything that had happened that morning in this journal.

I must have slept afterward, for when I awoke, the door was open and a little lamp burned in an alcove in the wall, casting shadows across the room. When one of them moved, I sat up quickly.

“Don’t be afraid,” the shadow said, and I saw its owner, a girl a couple of years older than me. She told me she was a slave too and that I would be happy here, for the master was a kind and generous man. “And his wife doesn’t whip us unless we deserve it!” she added. I asked her name, but before answering, she leaned out of the door and bellowed, “She is awake!”

She had just told me she was called Cytheris when a tall and finely dressed woman swept into the room and shooed her out.

“Iliona — that is your name, isn’t it?” the woman asked, turning to me. “I want you to know how welcome you are,” she said, but didn’t smile.

I asked if I could see Apollo. She looked puzzled, then left the room. A moment later, my little brother shuffled in.

I jumped up and threw my arms around his neck. We sat for a moment on the bed together, but before we had time to say much, the woman came back. In her arms was a sleeping child, about a year old.

The overseer followed her in, so I guessed what was to come. I screamed and begged him not to take Apollo, but it made no difference. He pushed us roughly apart.

Seeing my tears, the woman sat down and put her arm around my shoulder. This started me sobbing again, and the child awoke. I thought she would cry too, but instead she grabbed my hand and began sucking on my little finger.

More gently this time, her mother — my new mistress — began talking to me again. I was to be a companion and teacher for little Lydia, she said. I would also teach Greek to Lydia’s half brothers, Marcus and Lucullus. “We wanted to buy you because you already knew some Latin,” she explained.

Her arm around my shoulder, the warmth of the room, the child in her arms — all these things reminded me of home and my own mother — not in a sad way but (to my surprise) in a way that comforted me. And for a moment I forgot my sorrow and began to wonder if I might be happy here.

DAY III OF THE MONTH OF MAIUS, YEAR 890

I had imagined that a slave’s life here in Rome would be one of locks and chains, but there is nothing like that to keep me from running away.

Yet where would I run to, and why would I try? I am beginning to see that in Rome, slavery and freedom are not opposites, like night and day, or winter and summer. The poorest Roman citizens are worse off than many slaves. Here I have clothes (though it’s true they are simple linen), my stomach never aches with hunger (though the food is plain), and I can rest when I am tired.

I sleep in a room with Cytheris, and in this I feel I am lucky. She keeps me company and is teaching me much about Rome. Last night I learned about the calendar. Romans count the years from the date Rome was founded. The months are about thirty days long and are each differently named. The days are more difficult, and for now I will just make my diary by counting up from the first day of each month.

DAY IV

This day I began my studies. It was also the first time I had set foot outside since the auction. I had expected to study at home, as girls always do in Greece. But instead I went to school with Marcus and Lucullus. The three of us walked there through the streets with Cestius, the boys’ pedagogus.

I was surprised at how humble the school is. On Mytilini, Apollo studied in a grand building with a hundred other boys. This one was just a tiny room with a few stools and an armchair for the teacher. Cestius made fun of my surprise: “This is one of the better ones!” he told me. “Most boys sit in the street to study.”

Our class was not so different from my brother’s school in Mytilini. Mostly we write on the same wax-coated tablets, though my stylus is shaped like the letter T. With its flat end I can smooth out the wax when I make mistakes, which I think is a fine idea, for I make many.

We studied reading and writing from early morning until noon, when Cestius came back. We walked home along Etruscan Street, which is lined with the most exotic kinds of shops. In fact, my nose found the street before my eyes did, because all the incense and perfume sellers have their stalls here.

The street is very busy, and Cestius took my hand. “Keep your eyes peeled,” he told us, “for there are thieves around every corner here. They will skin you alive and sell you back your own hide before you even realize you’ve been robbed.”

We saw no thieves, but we did have to flatten ourselves against the wall as a huge cart rumbled past, carrying building stone and timber. Our limbs seemed to be more at risk than our purses!

DAY XVI OF MAIUS

Tomorrow we shall visit the baths. Though we have a bathroom here, with a small tub, Cytheris tells me we are going somewhere altogether more grand — to the baths of Nero, who ruled Rome fifty years ago. Cytheris says he was a cruel man hated by all Romans. His reputation earned him a saying: “What could be worse than Nero, or better than his baths?”

DAY XVII

How can I begin to describe Nero’s baths? They are more like a palace. The huge building towers above the neighborhood; a gurgling “aqueduct” (a river on legs) brings water from the distant hills, and steam pours from the windows. The baths are so cheap they are almost free. Anyone who has a quadrans — Rome’s smallest coin — can soak all afternoon.

It seemed that a visit to the baths was a chance for my mistress to show off how many slaves she can afford, for she insisted that every one of us come with her. We set off in the afternoon: two carried her in a litter, one walked ahead, and the rest of us followed.

Once we were inside and had changed into our subligari and mamillares, my mistress set one of us to guard our clothes and took two more to wash, oil, and massage her. The rest of us could do as we pleased for the afternoon.

Cytheris took me from room to room until we came to the hot bath, the steamy caldarium. Here we lounged, pampering each other until we met some friends of Cytheris’s. When she introduced me as newly enslaved, they were all very sorry for me.

As we talked, each revealed how she had become a slave. Most had been born of slave parents, but one blond girl, from Germany, had been taken by Roman soldiers when they crushed a revolt there.

DAY XX OF MAIUS

A fortnight ago, I wrote a letter to Apollo and gave it to my mistress. She promised that the overseer, who regularly travels between Rome and the farm, would take it to him, but I have had no reply.

DAY XXV

This morning I awoke with a thundercloud around my head. I had dreamed that Apollo and I were back on Mytilini, doing the things we used to do together before we were captured — running on the open hills and swimming in the sea. When I awoke, the walls around me felt like a prison.

My master saw my long face, and I told him about my dream. He tried to make me feel better about living here in Rome, finishing by saying, “There is always a chance of manumission.” I didn’t understand this Latin word, so he explained that good and obedient slaves may be freed through the kindness of their masters or may buy their freedom with the money they earn.

His words lifted my stifling gloom, and I began to hope that I might not live my whole life as a slave.

DAY XXVII

I learned today that the older brother of Marcus and Lucullus is a legionnaire who will be returning to Rome soon for the triumph of the emperor Trajan. This grand parade is to celebrate the victory of Roman forces in Dacia, and it will be a fantastic spectacle that all of Rome will watch.

DAY XXIX

I made the mistake of talking to Cytheris about manumission. “Are you mad?” she exploded. “We earn a few asses’ pocket money a week for our sweat and toil around this house. There are 16 asses in a denarius. They paid 500 denarii for you. It would take three lifetimes of work for you to buy your freedom.” Then she threw a cushion at me and ran from the room in tears.

Now I am as full of sorrow as before — and guilt, too, for having reminded her of how hopelessly trapped we both are.

DAY I OF THE MONTH OF IUNIUS

My mistress sent me on an errand this morning. It was the first time I have ventured out into Rome’s streets on my own. My task was to collect some embroidery from a seamstress who lived on the top floor of an apartment block.

Even by the standards of Rome, which are low, the building was a crumbling wreck. The seamstress was hurrying to pack and practically threw the work at me. “The walls will come down, Greek girl,” she warned me, “sure as Trajan’s the emperor.”

As I hurried down the stairs, I saw everyone else who dwelled or worked there leaving. One just jerked his thumb over his shoulder and said, “Hasten!” A huge crack had appeared in the side of the building! I did just that and breathed a sigh of relief when I was out in the street once more.

But my ordeal was not yet over. It was no great distance back to my home, but the streets lack signs and names, and finding your way is more like guesswork than navigation. In my haste, I took a wrong turn and in vain gazed about me for a shop, a house, a tree that I recognized. As I struggled, I heard a voice behind me.

“Are you lost?”

I spun around to face an elderly, white-haired man dressed in a clean and neatly pressed toga. Such was my panic that I could not remember a word of Latin and answered in Greek. “Yes! Where am I?”

To my amazement, he replied in Greek. “I am Greek too, though I have lived here most of my life. Where do you live?”

I told him that my master’s house was on the Quirinal Hill, not far from Hill Gate, and close to where a huge fig tree grows. “I know the place,” the old man said. He beckoned to me to follow, and within a fourth part of an hour, he had led me home.

I turned around to thank my newfound friend, but he was already ten paces away. “You are lucky. Gaius Martius is a good man,” he called over his shoulder.

I was too far away to reply, so I just waved. I wonder if I will see him again to thank him properly for his help?

DAY III OF IUNIUS

I learned that the apartments I visited collapsed just an hour after I was there. Cytheris didn’t even seem surprised. “Two or three come down each week,” she said.

DAY V

The task of emptying the chamber pots is shared among all the slaves. Today it was my turn. I was about to empty them into the drain next to the kitchen, when Cytheris hissed, “Stop!”

She explained that urine is used here in Rome for cleaning clothes and is bought and sold and even taxed!

I found this hard to believe, but that night a stinking wagon drew up and the driver tipped the foul liquid into a jar.

For this (Cytheris told me), we receive a few quadrantes each week. I have decided that I shall save mine to buy Apollo’s freedom.

DAY VII OF IUNIUS

We were woken last night by a tremendous tumult. My master’s eldest son, Cratinus, had returned. He had tried to slip in through the back door without attracting attention, but instead awoke the doorman, who took him for an intruder and challenged him. By the time the misunderstanding had been untangled, the whole house was awake and gathered in the peristylum.

Cratinus seemed to me very haughty and pleased with himself, and I was soon bored with the spectacle and slipped back to bed.

DAY VIII

Cratinus is just like the soldiers who guard the fort on Mytilini: they think armor and scars make it impossible for girls to resist their charms. I had to endure an hour of his stories about how brave he had been in Dacia. It was dull in the extreme, though he did make me laugh once or twice.

DAY X

I foolishly smiled at Cratinus this morning when I was in the kitchen preparing food for baby Lydia. Taking this as encouragement, he pinched my bottom. I spun around and spat out my fury at him, ending with, “And if you pinch me again, I shall tell your parents!”

At this, he threw back his head and laughed. “Tell them. Tell anyone you like. Tell all of Rome. For you are just a slave girl, and I can do whatever I like.”

I think he would have gone further if I had not been holding a kitchen knife. But he just picked up a fig, pushed it whole into his fat mouth, and walked out into the atrium.

DAY XI OF IUNIUS

Cratinus has injured his foot. He was showing off to his brothers in the peristylum, pretending to assault a statue, when his sword glanced off its marble arm, and nearly took off one of his toes. Now he worries that he will not be able to march in Emperor Trajan’s triumph in six days’ time. I shall be glad if he cannot.

DAY XIII

At dinner today, I brought in a dish just as the family were teasing Cratinus about his endless war stories. Suddenly he lost his temper. “Do you want to know what Dacia was really like?” he yelled. Without waiting for a reply, he continued: “Shall I tell you how Decebalus set fire to everything as he retreated so that we would have nothing to eat as we followed him?

“Or perhaps you’d like to know about the Battle of Tapae? Oh, yes, our emperor’s great victory — but it wasn’t quite as glorious as you may have heard. The grass was red with Roman blood, and there were so many injured that the emperor tore his cloak into strips to make bandages.”

For a moment, it was so quiet that I could hear the fountain outside in the atrium, then our master said quietly, “Cratinus, we know how much you have suffered, but there are children here. Why don’t you go and rest?”

Cratinus got up and slowly left the room.

After that, I felt a little sorry for Cratinus. All the same, I was relieved to learn from Cytheris that he will not be with us for much longer. His legion will leave Rome directly after the triumph.

DAY XV OF IUNIUS

Our complete household was in a state of great excitement at the thought of watching today’s triumph — all except for Cytheris, who had to stay behind to look after little Lydia. We had been fighting for a week over which of us would go. In the end Cestius tossed dice and I won, which threw Cytheris into a great sulk.

It was still dark when we left the house, but the streets were turned almost as bright as day by the torches of the people who had flocked to see the spectacle. They so crowded the street that my master and mistress were forced to abandon their sedan chairs and walk like common people. They shuffled slowly to Octavian’s Walks, where the senators and other dignitaries were to greet the emperor. I went with Marcus, Lucullus, Cestius and the other seven slaves to find a place to stand.

We seemed to wait forever before there was anything to look at. While we hopped impatiently from foot to foot, I spotted some distance away the white-haired Greek who had helped me home. I yelled and waved, but he did not hear me. Then a terrific roar from the crowd told us the parade had begun, and a moment later soldiers in brilliant, shiny armor filled the road to the bursting point.

I looked for Cratinus, thinking I would spot him from his limp, but all the troops marched in perfect time. Then I saw the emperor himself, in a magnificent golden chariot, drawn by four white horses. A slave held a laurel wreath above his head. He wore no helmet, and I realized for the first time that he was just a man like any other.

When I told Cestius I thought I had expected to see a god, he snorted. “All emperors think they’re gods.”

When Trajan and more of his troops had passed, I picked up my cloak. But Marcus hissed, “Not YET! WATCH!” Turning back, I thought I was seeing something magical. For around the corner came an entire building, several stories in height. A hundred bearers carried it on their shoulders, moving at a brisk walk. Another of these great floats followed, then many more, so that the procession continued for another hour.

Following behind was a sad sight: thousands of chained prisoners taken captive in the war with the Dacians walked behind their leaders. These men all knew they were living their last minutes.

The crowd now began to press toward the Forum to see the fate that awaits those who oppose the mighty Roman Empire. But I had no taste for this, and even the boys looked pale.

We hurried home as quickly as we could.

DAY XX OF IUNIUS

I am soon to see my brother again! As I sat with Lydia this afternoon, Cytheris came and told me that in one month we shall be traveling to my master’s estate in the Sabine Hills. We shall stay there through the hottest weeks of the summer — and I shall have the chance to spend some time with Apollo, if his work allows. I am glad, for he has not replied to any of the letters I have sent him.

DAY XXII

This day our master went to sit in the Senate, which always causes much upheaval. He dreads going, but loves it when he gets there. Making Rome’s laws makes him feel important, and he sees all his friends. Most are very old, and I suspect that they take secret bets on which of them will die first.

It was halfway through the morning when my mistress let out a shriek. “Hell’s teeth, he’s left his medicine behind!” I looked around, and sure enough, in a niche by the door was my master’s flask of sea-grape wine. “Iliona, take it to him, or truly he will cough his lungs up.”

I dashed to the Forum and rushed through the door of the Senate House without stopping. Too late, I realized that the passageway led straight into the Senate chamber. I found myself surrounded by Rome’s greatest, richest men.

The room fell silent.

“Young lady,” a senator finally addressed me, “I assume that your dramatic appearance is of the utmost importance, since the very future of Rome hangs upon the debate it interrupted.”

Scanning the rows of seats, I spotted my master and held up the flask. “Senator Martius, you forgot your sea-grape wine.”

There was another unbearable silence. Then I heard a stifled snigger from a younger senator at the back. One of his neighbors guffawed, and at length laughter echoed around the chamber. When it died down, someone shouted, “Take your potion, Gaius. Your coughing has been driving us all mad!”

As the laughter started again, a hand pulled the vial from my grip, and it was passed back to my master.

I didn’t wait to see him drink, but fled the chamber as quickly as I had entered it.

DAY I OF THE MONTH OF IULIUS

This morning there was silence from the kitchen, which normally rings with the sound of water flowing endlessly from a pipe on the wall into a stone basin below.

“The aqueduct has burst once more!” my mistress exclaimed when she came down.

In Mytilini, water always came from a well, never from a spout in the wall. She explained that our water here comes from springs four days’ journey away. “It’s beautiful, clear water, but to flow here, it crosses deep valleys on high, arched bridges. In other places it flows underground, through tunnels. Because of its length — more than 60,000 paces — the channel is always leaking.”

In my first week in Rome, I had marveled at the luxury of having water running in the house but soon took it for granted. Now I appreciate it once more, for I have to pick up an amphora and join a long line of slaves at the fountain in the street outside.

DAY II OF IULIUS

Little Lydia said her first Greek word today! It was Mamme — Mom in Greek. I cannot tell my mistress. She would be furious if she knew I spoke Greek to the baby and madder still if she knew Lydia thought I was her mother!

DAY V

We still have no water in the house, and today an errand took me past the aqueduct. From a gap in its side spills a torrent of water that rushes down onto the roofs of the houses below. On the bridge I saw stonemasons at work trying to block the hole with bags full of sand. Quite a crowd had gathered to watch, and I listened as a man shouted angrily at the supervisor of the water repairs. Judging from his fine new toga, he was very wealthy.

“Why do the street fountains still flow when the water in my house has dried up?” the rich man demanded. “Beggars may drink, while my fountain is silent!”

The supervisor of the water repairs let out a deep sigh before replying with exaggerated respect: “Because, sir, inside the castellum there is a barrier. Normally there is enough water to flow over it and into the pipes that lead into your fine abode”— here he made a little bow — “but if the aqueduct bursts or leaks, the level falls. Then your pipes are cut off, but water continues to flow to the public fountains. In this way”— he paused before delivering his crushing last line —“the poorest citizens in Rome do not have the free water taken from them by those who can afford a supply to their own homes.”

This bold response brought a round of applause, for we had all expected the official to grovel to such a wealthy, important man.

Sniffing defeat, the man edged away, muttering, “Ah, yes, I see. Thank you for that clear explanation,” as he tried to hide his embarrassment.

DAY XX OF IULIUS

We were supposed to leave for the country today, but during a thunderstorm last night, lightning bolts flashed in the direction of the Sabine Hills and everyone (but me) feared it was a sign that we should not travel.

To check whether it was truly a bad omen, my mistress went to the temple of Jupiter Tonans, a thunder god, taking with her an offering of a chicken. (Cytheris says she cannot think the omen too serious, or she would have taken a pig at least.) She came back saying that it is safe to travel, so we depart tomorrow.

DAY XXI

On this day I was woken by the snorts and braying of the donkeys and the iron-ringed wheels of the two raedae they were pulling. We were to make an early start, since builders’ carts are the only wagons allowed into the crowded streets during the day.

“Get a move on!” the driver was grumbling when I went outside. “I’ll be fined if we’re not through Hill Gate by dawn.”

I helped the others load the carriages with everything we would need on our journey. (Fortunately we had little luggage: most of it had left yesterday on a train of mules.) Then we flung ourselves inside.

And so we set off, driving along High Lane in complete darkness, guided by torches on the front-most carriage.

By the time the sun rose, we had left the walls of Rome behind us and were traveling through fields of waving flowers. These made me long for Mytilini, for in spring the hills there are a mass of different colors. These flowers, though, were in rows and all alike, and Cestius tells me they are grown for the vases of the city. In other fields lettuce and vegetables grew, and huge flocks of chickens scratched in the dust.

The heat, the early start, the rocking of the carriage, and the unchanging view (for the road was dead straight) all competed to see which could make me drowsy first.

My head flopped, and I jerked it upright a dozen times before finlly falling fast asleep. A loud shout woke me, and Cytheris grabbed my arm. I had slumped sideways and was about to fall out of the carriage tailgate.

I was shaking like a reed in a gale when she pulled me back inside. The road is surfaced with square stones so that it may resist the heaviest wagons without breaking up. Worse, the shout had come from a postman riding his horse at a gallop. Between the hard road and his horse’s hooves, my head would have been well and truly broken had I fallen.

When at last we arrived at the farm, it was dark once more. Marcus and Lucullus leaped down at the end of the drive and raced ahead of us to the door, which was lit by torches. More of these cast puddles of light on a few patches of white wall and overhanging olive trees. Everything else disappeared into inky darkness.

Before we left Rome, I had imagined that I would rush around the farm until I found Apollo, but I was so exhausted that I simply collapsed onto my bed and fell instantly asleep.

DAY XXII OF IULIUS

From the moment I awoke this morning, I could think only of finding Apollo. Yet this was the very thing I could not do, for the villa is a very different place from our house in Rome. There, my master and mistress lead busy lives and hardly notice if one of us is missing. Here, they are idle, with nothing better to do than to count us and ask, “Where’s Cytheris?” or “I haven’t seen Iliona for some time. Where’s she gone?”

So instead of searching for my brother, I had to be content with glancing from the windows to see if I could spot him. When I finally plucked up the courage to ask whether I could see Apollo, my mistress said curtly, “Perhaps tomorrow,” and sent me to put the baby to bed.

Here Cytheris and I have separate rooms. We all retired early to bed this evening, which has given me plenty of time to write in this diary.

DAY XXV

I have finally met Apollo! Having seen me sulking and kicking my heels about my tasks, my master asked me what the matter was, and I said I longed to see my brother.

“Then you shall!” he said, and sent a message that the bailiff, who runs the farm, should fetch him.

When the bailiff finally arrived with a boy, I stared and blinked. Was this Apollo? Only when he spoke my name was I sure, and I ran and threw my arms around him. Then I stood back and gazed at him. He was quite changed. He wasn’t just thinner; he had bruises on his arms and a red scar around one ankle. Worse, perhaps, were his eyes. They darted left and right, and he had the expression that I once saw on the face of a stag as it fled from the hunt.

I asked him if he was all right, and before answering, Apollo turned to the bailiff. Only when the man nodded did he reply — and then in stuttering Latin. “I’m fine,” he said. “They treat us well here. The work is not too hard, and we get enough to eat. . . . ”

All this came without expression, like the worst actors I had seen in the theater on Mytilini. Then he said in Greek, “I’ve missed you, but I cannot stay long. We are weeding the vines, and if I don’t return, my friends will have to do my row as well as their own. Good-bye.”

He kissed me and was gone.

DAY XXVI OF IULIUS

I have made friends with the house dogs. They are huge and black — whereas the herders’ dogs are all white. I was curious about this and asked the bailiff, who told me, “Why, think about it, girl. A guard dog must be black so that thieves who come in the night cannot see him. A herder’s dog is better off white so that he is not mistaken for a wolf.”

DAY XXVII

Last night I was woken by the small noise of something dry and hard falling on the floor of my room. Outside, I heard the slap of bare feet running from my window. I crawled around to try to find whatever had been thrown in, but it was too dark. In the morning, I found a short piece of bone. One side was scratched in a pattern. I took it to the window, and in the sunlight, I realized I was holding it upside down. There, in tiny Greek letters, was a message: come our huts in 2 nights.

I didn’t know how Apollo found out which room was mine. Nor did I think I could wait that long to see him again, but I had no choice. So I continued with my tasks as if I were still in Rome.

Here, though, time seems to crawl past, for in fact, there is little for us to do. This morning, my mistress decided that she would like to take a walk with the baby while Cestius was teaching the boys. What this really meant was that she walked while I carried Lydia.

From the road we could look down at row upon row of vines stretching down into the valley — and up, to the steeper slopes lined with olive trees. My mistress’s conversation was mostly about how difficult it was to make money from a vineyard. I paid little attention until I heard her saying, “And that’s where the laborers live.”

DAY XXIX OF IULIUS

Zeus must have been smiling on me last night, for there was a full moon. Once everyone was in bed, I had no difficulty slipping out the window and running down the drive through the moon shadows of the olive trees. Now I have learned the truth about Apollo’s life on the farm.

“Iliona, I can’t begin to describe how awful it is here,” he told me. “We are prisoners. We live mostly on coarse bread and olives and work eight days in every nine from dawn until dusk.”

I asked him what happened to his ankle.

“One of us tried to escape. They picked him up, whipped him, shaved his head, and branded his leg with an F for fugitivus — a runaway.”

“But your ankle?”

“I’m coming to that. The overseer said we must all have known about the escape, so for a month we worked in chains. Then Gaius Martius arrived without warning one day and saw what we were enduring. He fired the overseer and put an old slave in his place. Now things are not as bad as they were — we have new clothes and time to rest in the hottest hours.”

A dog began to bark, and I was glad I had made friends with them. Apollo poked his head out of the hut. “You had better go. Don’t try to come here again. It will be trouble for both of us.” He pushed me out, and I sprinted back to the villa.

Only this morning did I realize how close I had come to discovery, for the daylight revealed my dusty footprints, leading from the drive to my window!

DAY XV OF THE MONTH OF AUGUSTUS

Our stay in the hills finished yesterday, and we are back in Rome. I did not see Apollo again, apart from when we came only close enough to wave. My mistress frowned a silent warning when I asked if we could talk.

We had one exciting moment when rumors spread of slaves deserting a nearby farm. The shutters went up, and the dogs were released in case we should all have our throats cut in the night by the fugitivi. In the end, though, it turned out to be false gossip.

DAY XX

Yesterday I nearly lost my life — and became a heroine (though I am not sure I deserve the glory heaped on my shoulders)!

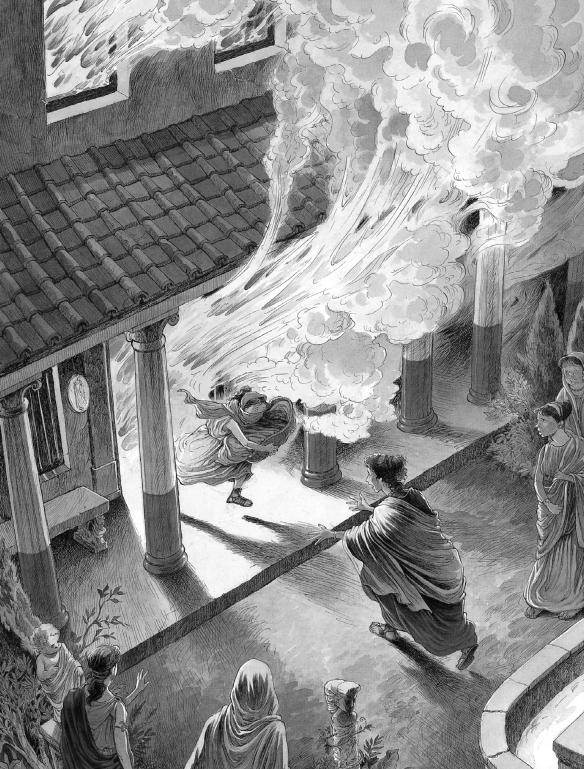

The day began normally enough: we set out for Agrippa’s baths (not as nice as Nero’s, for the water is less clear). We did not linger as long as usual, but instead went to the house of my mistress’s friend nearby. Lydia was sleeping, and I took her crib to the other end of the house.

Not long after, there was a smell of smoke. Nobody was concerned, for there is always smoke in Rome from people lighting cooking or heating fires with small wood, to set the charcoal alight. But the conversation turned to fires, such as the great fire fifty years ago that destroyed most of Rome.

Even when we heard cries in the street, there was no alarm. Our hostess looked out but returned, saying, “The fire is distant, and the wind blows it away from here.”

But then came a loud hammering at the door. A boy hardly older than me, his face black with soot, asked for buckets, adding, “Look out! The flames are attacking your walls!” At this exact moment, a billow of smoke blew into the room, as if Adranos, the fire god himself, had heard him.

Everyone rushed toward the peristylum. As soon as we got outside, we heard loud crackling and felt heat on our faces. Hungry flames licked toward the room where Lydia slept, but nobody did anything. While my mistress sobbed, all the other women wrung their hands. One muttered, “At least it isn’t a male child.”

Their stupidity made me furious and foolhardy. I plunged into the pool in the middle of the peristylum to soak my clothes and covered my face with my wet scarf. Then I dashed toward the open door.

For the rest of my story, I rely on others, for all I remember is waking up in bed at home and immediately retching a foul black paste onto the bedclothes. When the room ceased to spin around me, I saw Cytheris, who whispered, “I fetched our master from the Senate,” and pointed to where he stood with my mistress at the end of the bed. They beamed, and my mistress said quietly, “You did a brave and fine thing, Iliona. We shall not forget this.”

DAY XXV OF AUGUSTUS

Today my mistress received a letter from her brother, a legionary commander stationed on the outer edges of the empire. He is on a big cold island called Britannia, somewhere far to the north. It is farther even than Dacia, where Cratinus fought. And he does not like it.

The letter started an argument between my master and mistress. When she took her brother’s part — that Britannia is cold and the people ignorant and not worth ruling — my master shrugged. “You forget, my dear, that Rome grows strong by conquest. From these new provinces we get slaves and treasure. It’s true that Britannia is, so far, a disappointment, but from Dacia, Trajan brought back half a million pounds of gold and double that weight of silver. And if the emperor had not defeated the Dacians, they would grow bolder. Soon they would be attacking Rome itself.”

DAY XXVII

On the way to school I asked Cestius about Rome’s provinces, and before our class started, he pointed to a map pinned on the wall. “Look, here is the known world — Rome rules the part colored red. How much is left?” I had to admit that most of the map was red.

When Cestius returned, he led us a different way home, through the Forum. When we reached a food stall, he pointed to everything on sale, saying, “Look: the grain comes from Egypt, the oil from Spain, the salt pork from Gaul — all Roman provinces.” Next door, at a hide and fabric shop, the same: “Here is Egyptian linen, African cotton, leather from Britannia and furs from Asia Minor.”

Then he stepped into the street and ran his hand over the shiny stone pillar. “The marble that made this pillar came from your country, Iliona. So you see, almost everything we have in Rome comes from distant regions that our great city rules.”

DAY XXX OF AUGUSTUS

Though my mistress always looks well put together, I had no idea until today how much effort is needed to achieve this effect.

After waiting an hour for Psecas, her ornatrix, who comes to the house each day to do her hair, she called me into her room. She was staring into a bronze mirror and applying the finishing touches to her face. She was wearing only an undershirt and called out, “Pass me that clean tunic, Iliona,” without taking her eyes away from the mirror. Lying across the bed was a plain white tunic made of the finest silk I have ever seen. I couldn’t resist running my hands through the fabric as I handed it to her.

However, it wasn’t her clothing that took the time, but her hair. At first she was patient, but when my work collapsed in a clumsy heap around her shoulders, she flew into a rage, shouting words I have only heard women in the marketplace use.

But at last she calmed down, and between us, we made of her hair something that approached its normal appearance. As I left, she gave me four shiny denarii, saying, “We shall make an ornatrix of you yet, and I can fire that lazy slug Psecas.”

I have put the coin under the loose tile on the floor with the others I have been saving to free Apollo.

DAY II OF THE MONTH OF SEPTEMBER

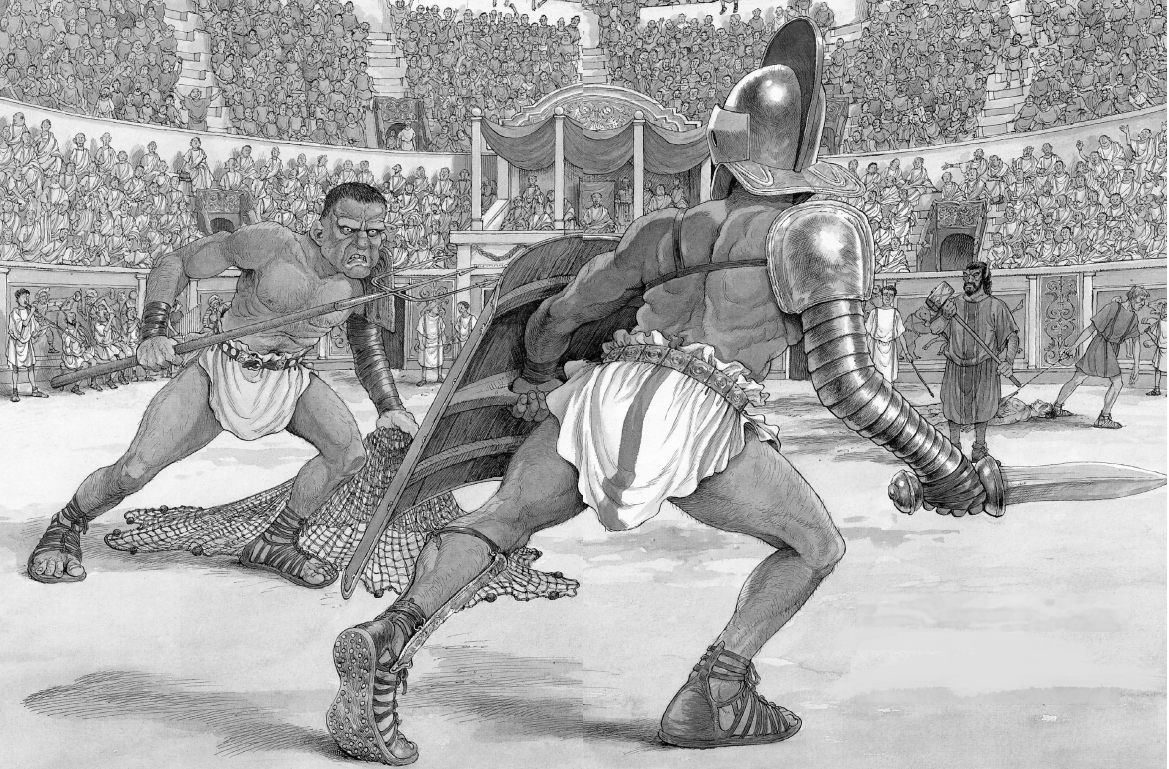

I do not know how I should write about what I have seen today. We went to the munera — the “games”— at the amphitheater. But these are not like games I have ever played: they are real battles betwen two slaves, called gladiators, who fight with razor-sharp weapons. Today’s games were the gift of the emperor to the people, as part of the celebration of the Dacian tiumph.

The gladiators fight in a big open oval of sand in the middle of the arena. All around rise thousands of seats. To sit in one, you must have a wooden token. My mistress gave one each to Cytheris and me as a treat. “Come and sit with me. We’ll be right at the top!”

She wasn’t joking. Women and slaves sit on the highest tier, and low seats are reserved for the most important Romans, with senators — such as my master — at the very front. At first I was disappointed to be so far away, but when the spectacle began, I was glad. We could not smell the blood, nor see the fear on the faces of the defeated gladiators.

The first match was between a net man and a pursuer. Though the pursuer fought bravely, he soon grew exhausted. When at last he stumbled, the net man stood with his trident touching the pursuer’s chest and turned to the emperor’s box for a signal.

I looked away, but my mistress pulled at my arm, saying, “Iliona, don’t worry. The pursuer fought well. The emperor will listen to the crowd.” Looking up, I saw the emperor spare the defeated man and reward the winner with a wooden sword, which meant he had won his freedom.

During the next fight, I watched everything. And by the third, I was actually enjoying it. The roar of the crowd ringing in my ears swept me along, as a strong wind blows down the road. But when the show ended, I felt ashamed.

As we lined up to get out, we met my master, who had a surprise for us. He led us away from the crowd and down into a basement below the arena. Here we saw ferocious lions, tigers, and leopards pacing in their cages. They will fight in the ring tomorrow afternoon.

The trainer of beasts told us that the animals are usually terrified of the gladiators who challenge them. Despite the excitement of the spectacle, I went home with a sad heart.

DAY X OF SEPTEMBER

Today we accompanied my master on a visit to the site of some new baths. People say they will be finer than Nero’s — and the biggest that Rome has ever seen. My master is one of the senators who encouraged the emperor to build these baths, in spite of the great cost of their construction.

We left at an early hour, before the sun got too hot. Several of the house slaves carried my master and mistress in chairs. Cytheris and I followed behind, talking. The baths stand just up the hill from the amphitheater, and it is easy to see them from wherever you are in the city.

As we arrived, an important-looking man asked me in Greek, “Would you like to climb to the top?” He must have heard my accent. Of course I replied “Yes!” in Greek, and he called over a mason, who led me to a huge basket.

As soon as I stepped into it, the mason jumped in after me and waved his arm. At this signal, two men began to walk inside a great wheel high above, setting it turning. To my great alarm, this made the basket rise into the air.

Higher and higher it climbed, until I could see every part of the baths. And I was astonished to learn that the walls are but a TRICK! From the outside, they look like solid marble, but in fact, they are not at all.

The mason showed me how the builders mix lime with water and a kind of dust called pozzolana so that it turns into a dark gray mess, which they pour between molds made of wooden planks. Within days, the mess turns hard, so that it stands up on its own, without the wooden molds. Then the mason covers it in thin slabs of stone, though they look like solid blocks.

When I got back down to the steady ground, I could not find the Greek man to thank. On the way home, my mistress told me he is not Greek at all, but Syrian. “That was Apollodorus, the Emperor’s architect himself!”

DAY XV OF SEPTEMBER

Cytheris is very proud. She has made friends with a stagehand at the theater of Pompey, who will let us into a performance there tomorrow afternoon. Our mistress will not learn of it, for she plans a visit to the temple at the same time and does not want anyone to come with her.

DAY XVI

Pompey’s theater is near Nero’s baths, on the low ground by the big bend in the river. Inside, there is enough room for an audience of 20,000 to sit down. Not that they ever do! In all the time we were there, hardly anyone stayed in their seats. They stood up to applaud and cheer — or to shout and heckle the actors. They walked back and forth, too. Just as we arrived, half the audience left to watch a tightrope-walker in another part of the city.

The performance was unlike anything I have ever seen before. Cytheris called it a “pantomime.” The star of this show stood at the center of the stage, chanting and speaking at the top of his lungs. Meanwhile, slaves made music with rattles, cymbals, drums, and gongs.

The rest of the cast acted out the story in silence. The sweeping movements they made with their arms meant that those in the farthest seats could understand the action — even if they spoke only a little Latin.

I did not like the story! The chanting star told how a woman cheated her husband. When some of the women in the cast took off their clothes, I covered my eyes — though most of the audience roared with laughter. One of the actors spotted us and practically lifted us from our seats, telling us, “This is no place for girls as young as you!” I was embarrassed but relieved that I didn’t have to watch any more.

The most extraordinary sight completed our wicked trip. As we were marched to the exit, Cytheris hissed, “Look! LOOK!”

I followed her eyes and saw our mistress sitting with some women friends in the seats above us, and she was laughing as loud as any of them. I put my finger to my lips, and we hurried home.

DAY XX OF SEPTEMBER

Today my mistress announced that she is to hold a banquet in honor of two newly appointed senators. “Nothing too grand,” she added, “just nine of us.” However, I have heard much of Roman banquets, and our cook was terrified at the thought of all the work. He ran around moaning, “How will we manage in our tiny kitchen?” He was calmed only when my mistress assured him that a caterer will prepare most of the food and we will only reheat it here.

DAY XXIII OF SEPTEMBER

I cannot quite believe the quantity of stuff that fills the kitchen and another room besides. Some of it I do not even recognize. The butcher brought some beasts like rats, skinned and sewn up along the belly. I asked him what they were, and he cheerfully replied, “Them’s stuffed dormice, young lady. You cook them on a spit.” I felt quite sick.

DAY XXIV

My task tonight is to stand at the side of the room with a jug of perfumed water and a towel, and before guests lie down to eat, I shall wash and dry their hands and feet. I shall wash their hands between courses, too, if they command me to do so. This seems deadly dull, but I shall at least have the chance to listen to the conversation.

DAY XXVIII

I am so exhausted I can hardly write, though the feast finished more than a day ago. The guests began to arrive as the sun was setting and were still here when it rose.

I have never seen such food! First there was shellfish: mountains of oysters, mussels, and spiny sea-hedgehogs. Then tiny songbirds huddled together on a golden platter. The stuffed dormice I had seen earlier arrived dipped in honey and rolled in tiny black seeds. The main courses were kid, suckling pig, and sow’s udder — all stuffed and roasted.

There were entertainers, too — dancing girls who tumbled and leaped in the air, musicians from Africa, a dwarf who ate fire, and a hunchback who told jokes about everyone there.

Of course there was wine: warmed wine, wine chilled with snow from the mountaintops, wine sweetened with honey, wine flavored with costly spices. And then yet more wine, mixed with water just as people normally drink it.

Indeed, it was too much wine that ended the evening. One of the guests started talking about the new baths. He did not know how attached my master is to the project and began to rave about how “its great cost will destroy the empire.”

When he finished, my master turned purple with rage. Nobody else dared to speak. Moments later he left for his room, trembling like a leaf.

The argument shook everyone, and I felt exhausted by it (and by standing on my feet all night). When I got to bed, I fell instantly asleep and awoke only when it was night once more.

DAY XXIX OF SEPTEMBER

Our small quiet world was turned upside down yesterday. My master seemed weak and ill when he rose in the morning. When he complained of pains in his chest and numbness in his left arm, my mistress tried gently to persuade him not to attend the Senate. But he was determined to go and set off in a litter, gripping his vial of sea-grape wine.

We learned later that at the Senate House he had to be almost carried to his favorite seat. The blow came when he stood to speak: his legs would not hold him, and he fell to the ground, clutching his chest.

The senators carried him home on a tabletop, and here he lies, in a darkened room. His pulse is weak, and he speaks few words. He drinks little and eats less.

Outside the silence of his room, my mistress wrings her hands and prays at the shrine by the front door. My master’s brother is here. He has used his influence to send a letter to Cratinus by the emperor’s messenger. It travels at the speed of a galloping horse and will reach him in a day, for he is now stationed not far from Rome. However, even if he hastens back with all possible speed, I fear he will be too late.

DAY XXX OF SEPTEMBER

During the night, a physician came to examine my master. The man was a Greek, like me. He arrived with four attendants but took only my mistress into the bedchamber where my master was lying.

When they came out, he was holding my mistress’s hand and reassuring her. However, as they passed a torchbearer, I glimpsed his eyes clearly and could see from their empty, hopeless look that he did not believe his own words.

An hour later, my master suffered another blow like the one that struck him yesterday. This time he did not recover. Now my master is dead.

DAY I OF THE MONTH OF OCTOBER

In the middle of the misery and mourning for my master, I have a reason to be joyful! The reading of his will has brought a fantastic and wonderful surprise.

Yesterday my master’s brother fetched the will from a temple nearby where it had been stored for safekeeping. He took it into the dining room to break the seals and read the wax panels to the family.

After about half an hour, I heard Cratinus (who arrived yesterday) shouting, then he stormed out of the room in a black mood, followed by everyone else. My master’s brother was the last to come out, and he called me over to sit with him in the peristylum. There he read to me the words that follow (for I borrowed the wax tablets and copied them):

For her bravery in saving my baby daughter from certain death in the flames of a house fire, I set free my slave Iliona immediately. I also set free her brother, Apollo, who shall be brought from my country estate to be reunited with his sister. In addition, I give to Iliona each year the sum of one hundred denarii.

I am free at last!

DAY III OF THE MONTH OF NOVEMBER

A month has passed since I last unrolled my diary and sharpened my quills. My life has changed so much — and yet it seems hardly to have changed at all. Apollo is with me, which makes us both very happy. My mistress sent for him several days after the will was read. He walked all the way to Rome rather than wait for a carriage to fetch him. Now he works here in the house, doing any tasks that require strength and skill — for his months on the farm have given him powerful arms, and hands that learn quickly.

Now that I am free, my mistress treats me better than she did before and even says “please” and “thank you” if she remembers.

Cytheris did not speak to me for a fortnight. Thankfully, though, we are friends once more.

I am spared some of the tasks I hated most, such as emptying the piss pots in the morning, but I am still studying and looking after little Lydia.

Apollo and I have talked about returning to Greece. We could perhaps save enough from our earnings to pay the fare. However, our parents are at the bottom of the sea, and we have few relatives in Mytilini. Furthermore, if pirates were to attack our ship on the journey, we might swiftly find ourselves back in Rome. Then our story would start again, just as it began a year ago, with chalk on our feet and wooden signs around our necks.

No, for the present we shall stay here, for my mistress’s home is now our home, and her family has become our family, too.