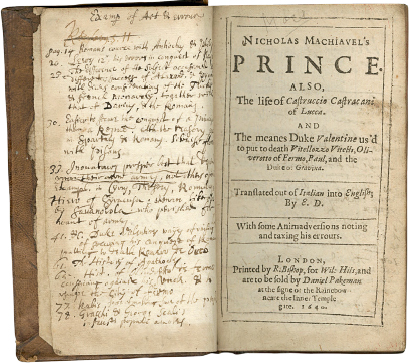

Published in 1532, and the first English translation from 1640.

Machiavelli’s political treatise on the art of getting and keeping power was based on his own observations of the machinations of kings, princes and popes. It caused controversy with its unethical recommendations, but five hundred years later it is still widely read by aspiring politicians.

Italy in the time of Machiavelli (1469–1527) was not the unified country we know today but a diverse collection of kingdoms centred on Naples, Rome, Venice, Milan and Florence. This fragmented political landscape was the target of regular invasions by neighbouring countries. Feuds between the Italian states and even within them were commonplace: for example, Florence, Machiavelli’s home, was the setting during his life of a long-running power struggle between the Medici and Borgia families.

On a diplomatic mission to France in 1500, he was impressed by the relative peace and stability of the country, ruled as a single nation by Louis XII. France frequently interfered in Italian affairs, and in a deal with the pope, Louis installed Cesare Borgia as ruler of Romagna, the province neighbouring Florence to the east. Borgia had a reputation for ruthless cruelty and cunning in pursuit of power, qualities that Machiavelli believed would be necessary to achieve his ideal of an Italy as united and stable as France.

He began to develop his ideas on paper, and an early handwritten draft of Il Principe (The Prince) was in circulation in 1513. Where previous authors argued that high office should be guided by high ethical morality, Machiavelli argued that too moral a sense of purpose could actually hinder a man’s ability to seize and exercise power.

Using real examples from Italian history, he made the case for strong, merciless rule in which it was only necessary for a leader to appear morally virtuous to retain the goodwill of the people. In a world of constant war between nations and states, he believed that efficient warfare, combined with tactical diplomacy, was the basis for successful statehood. War, rather than being an evil inevitability, was a necessary tool of government.

In short, the end – power – justified the means. This was political theory rooted in the real world, a practical manual for princes that only in the centuries following its publication has become a philosophy of political theory. When it was finally printed, five years after Machiavelli’s death, it was condemned for being immoral and unethical. An English-language edition was not printed until 1640, although several manuscript translations were thought to be in circulation by the end of the sixteenth century. Machiavelli’s understanding of human nature won admirers among the leaders of the English Civil War, the American Revolution, and the Chicago and New York mobs: John Gotti described it as the Mafia bible. The Prince has had a profound influence on world leaders from Henry VIII to Josef Stalin.

We use the word ‘Machiavellian’ to mean politically cunning or ruthlessly devious. In fact, his ideas are more complex than that, invoking concepts of civic pride and patriotism, which Machiavelli hoped would guide princes towards a strong and stable united Italy. Italy was finally unified in 1871.

Published in 1532, and the first English translation from 1640.