The 1819 edition with a frontispiece of ‘Brother and Sister’, showing an angel watching over the eponymous brother (transformed into a deer) and sister as they sleep.

Two hundred years ago two young German brothers published a collection of folklorist fairy tales that would become – despite their dark, blunt, and often cruel and brutal themes – the standard children’s book and one of the most influential and controversial literary works in Western culture.

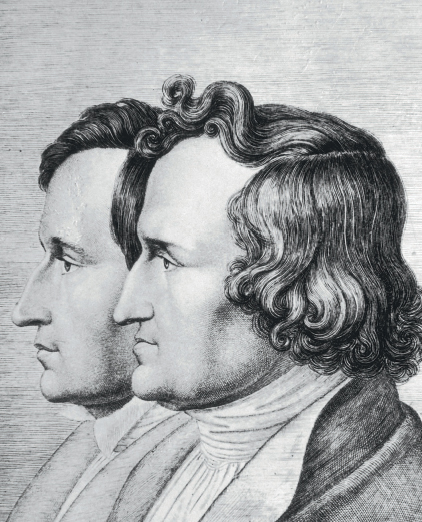

Jacob Grimm (1785–1863) and Wilhelm Grimm (1786–1859) were born into a relatively prosperous middle-class household in Hanau near Frankfurt, but their father’s death in 1796 plunged the family into poverty amid the turbulent period of the Napoleonic Wars. After their mother died in 1808, the brothers became fully responsible for the welfare of their three younger brothers and sister. Nevertheless, they persevered and found a way to support themselves and the others by drawing upon an interest they had acquired in childhood.

As boys, the pair had begun collecting traditional German folk tales and songs from their friends, and their fascination for the meanings and origins of such stories had led them to explore the new field of philology (the study of linguistics as the vehicle of literature and a representation of cultural history), which had sprouted in the fertile atmosphere of German Romanticism.

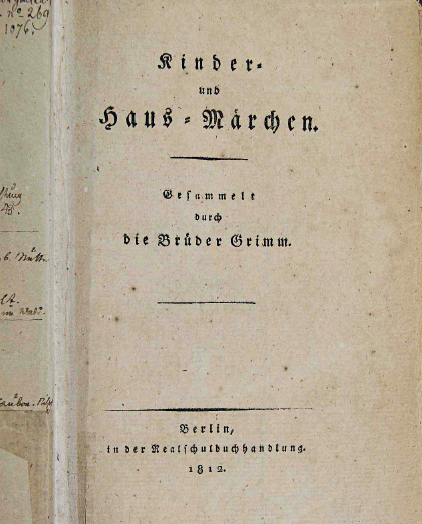

In 1812 they published a collection of eighty-six old German tales. The book was titled, Kinder und Haus-Märchen (Children’s and Household Tales), which came to be known as Grimm’s Fairy Tales.

Over the next forty years, the brothers brought out six subsequent editions, all of them extensively illustrated, first by Philipp Grot Johann, and later by Robert Leinweber. The stories introduced a host of immortal characters, including Rapunzel, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Cinderella, Little Red Riding Hood, the Frog Prince, Hansel and Gretel, the Golden Goose, Rumpelstiltskin and many others. Most contained elements of cruelty, violence, fear, loss and death that reflected the grim and unvarnished reality conveyed in the tales.

Versions of the tales were widely published in many languages and editions. They also became the basis of many Walt Disney motion pictures, starting with Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937). But the stories were controversial. The British poet W.H. Auden hailed them as ‘among the few indispensable, common-property books upon which Western culture can be founded… It is hardly too much to say that these tales rank next to the Bible in importance.’ But Adolf Hitler’s embrace of the works as exemplifying his Nazi race theories led to their being banned in some quarters.

The tales’ messages and meanings were the subject of The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales (1976) by the Austrian-born psychoanalyst and Holocaust survivor, Bruno Bettelheim, who argued that the tales helped children deal with such existential problems as separation anxiety, Oedipal conflict, and sibling rivalries, and served other constructive purposes in their psychological development. But those interpretations as well have often generated debate.

Philip Pullman, who retold some of their tales in 2012, explains: ‘Scholars of literature and folklore, of cultural and political history, theorists of a Freudian, Jungian, Christian, Marxist, structuralist, post-structuralist, feminist, postmodernist and every other kind of tendency have found immense riches for study in these tales.’ However they are interpreted, Kinder und Haus-Märchen defined the fairy tale and forever changed children’s literature.

The 1819 edition with a frontispiece of ‘Brother and Sister’, showing an angel watching over the eponymous brother (transformed into a deer) and sister as they sleep.

The title page of the original 1812 edition of Kinder und Haus-Märchen (Children’s and Household Tales).

Portrait of Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, by their younger brother Ludwig Emil Grimm.