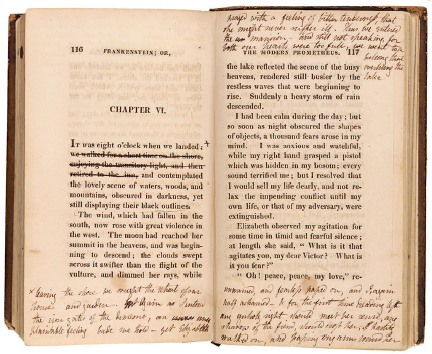

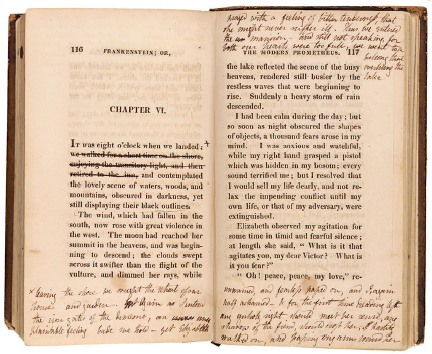

A copy of the first edition from 1818, with handwritten amendments by Mary Shelley, some of which were incorporated into subsequent editions of the book.

Frankenstein is the classic Gothic horror novel, and Shelley’s monstrous creation has provided the premise for hundreds of books, plays and films. Her original story discusses nature, responsibility, isolation and the dangers of using powerful knowledge.

Frankenstein was originally written as a challenge. Three friends were stuck indoors reading ghost stories to one another one cold evening in 1816 and decided to see who could write the best tale of horror. The friends were the poet Lord Byron, his doctor John Polidori, and Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, the daughter of the author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. The competition threw up two Gothic classics: Polidori’s The Vampyre, the first-ever vampire novel; and Mary’s Frankenstein.

Mary was there with her lover, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. The pair were married later that year, and Percy helped the new Mrs. Shelley (1797–1851) to expand her original short story into a novel over the following few months. Mary was inspired by the experiments of the Italian physicist Luigi Galvani, which proved that muscles could be animated with the application of an electric current – a phenomenon, christened Galvanism, that had been demonstrated publicly in 1803, on the body of a dead criminal in London.

Frankenstein was published in 1818, at a time when female novelists were still relatively rare. That fact, and the grisly subject matter, resulted in some mixed views from the critics of the day. But the book was an immediate success with the reading public, and within three years the first of many melodramatic versions of it appeared on the London stage.

The novel itself begins and ends with an epistolary framing device – the letters of an Arctic sea captain describing his meeting with Frankenstein, who has travelled to the frozen north to destroy the monster that he created. Shelley uses the icy wilderness to evoke the book’s recurring motif of isolation. As Shelley relates the story that Frankenstein told the captain, we find that Frankenstein too is isolated, by his obsession with creating life and his ability to do so. And no one is more isolated than Frankenstein’s monstrous creation, who is shunned, even by his creator.

The creature, although physically crude and brutish, is intellectually and emotionally mature – he reads Milton’s Paradise Lost, for example. He hopes that Frankenstein will create a companion for him; and only when Frankenstein, horrified by what he has made, dashes that hope does the monster seek violent revenge. But when in the end he finds that Frankenstein has died in the Arctic of hypothermia, he grieves, aware that he is now more alone, more isolated, than ever.

In the twenty-first century the book still raises moral and psychological questions about man playing God. These ideas fascinate almost as much as the lurid possibility, closer than ever, of creating life from spare parts.

A copy of the first edition from 1818, with handwritten amendments by Mary Shelley, some of which were incorporated into subsequent editions of the book.