Remembrance of Things Past

Marcel Proust

(1913–27)

A sprawling novel spanning several volumes, or a memoir about lost memories? Proust’s experimental masterpiece is now recognised as one of the most important works of fiction of the early twentieth century.

Born in a rural suburb of Paris, Marcel Proust (1871–1922) suffered from ill health throughout his life. It interrupted his education, his employment and his writing – as his early novel Jean Santeuil, left unfinished, can testify. Biographers have described him as a dilettante: someone who, thanks to wealthy parents, was able to dabble in many things without dedicating himself to anything in particular. But no one can doubt his commitment to Remembrance of Things Past, all one and a quarter million words of it.

The death of his parents in 1903 and 1905 seems to have spurred him to take writing more seriously. In 1904, he published a well-received translation of a work by the English art critic John Ruskin. Armed with Ruskin’s view of art in society, Proust revisited the themes of Jean Santeuil, and from 1909 onwards a new novel began to emerge from his pen, titled À la Recherche du Temps Perdu. It consumed him for the rest of his life, and he died before the publication of the last three volumes.

The title translates more accurately as In Search of Lost Time. ‘Remembrance of things past’, a phrase from a sonnet by Shakespeare about memory and loss, was the title chosen by C.K. Scott Moncrieff, who first translated the book into English in the 1920s.

Memory and loss are indeed the main themes of Proust’s book. In it, an unnamed narrator, a would-be writer, describes his uneventful life in minute detail, regretting time wasted and enjoying times won back by the power of memories – memories that can be triggered accidentally by the most unexpected and mundane events. The most famous of these occurs in Swann’s Way, the first volume: the narrator dips a madeleine – a small cake – into his tea, and the taste transports him back to childhood madeleines fed to him by his aunt.

Very little of consequence happens to the narrator. He falls in and out of love, gossips about other affairs and contemplates art; there is no drama, no conventional plot. For this reason academics still debate whether it is a traditional novel at all. But nor is it a true memoir. Although there are many similarities between the narrator and Proust, and between the narrator’s acquaintances and Proust’s, it is certainly a work of fiction.

More than anything it is, in its discussion of its themes and its descriptive passages, a work of the finest writing, a work of art that earns it the accolade of being the first modern novel. This is the Ruskinian approach: by his evocative writing, Proust and his narrator become not only authors but artists.

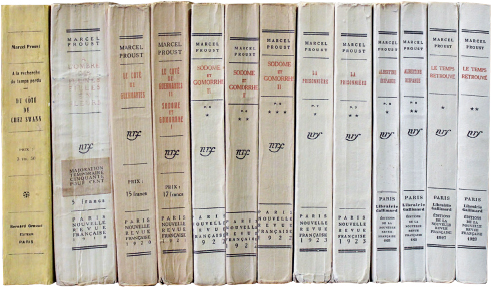

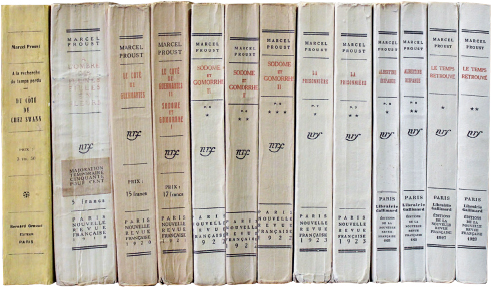

Proust’s masterpiece was published in thirteen volumes between 1913 and 1927. After being turned down by several publishers, including Gallimard, Proust paid for the publication of the first volume. Realising their error, Gallimard wooed Proust with dinner at the Ritz and went on to publish all subsequent volumes of his epic novel.