Following more than a decade of calculations and writing, a German physicist published his complete theory of relativity, which subsequent experiments would prove correct and which many scholars have since called ‘the biggest leap of the scientific imagination in history’ – ideas that continue to fuel inventions and dreams.

The German theoretical physicist Albert Einstein (1879–1955) first published his theory of special relativity in 1905, holding that the speed of light in a vacuum is independent of the motion of all observers, and the laws of physics are the same for all observers who are not moving or accelerating.

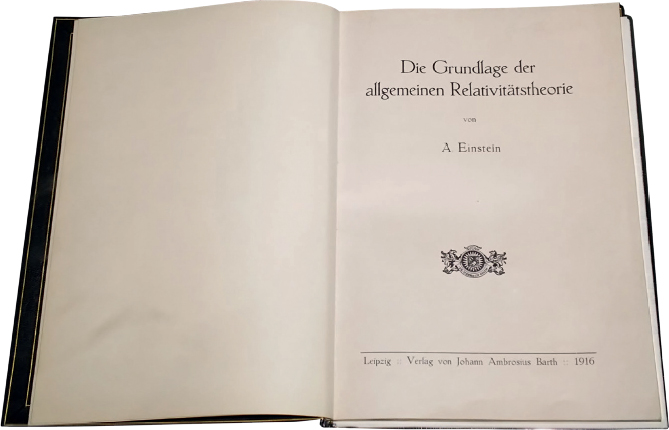

For the next ten years he worked on a related general theory of relativity that was published in a paper in 1915.

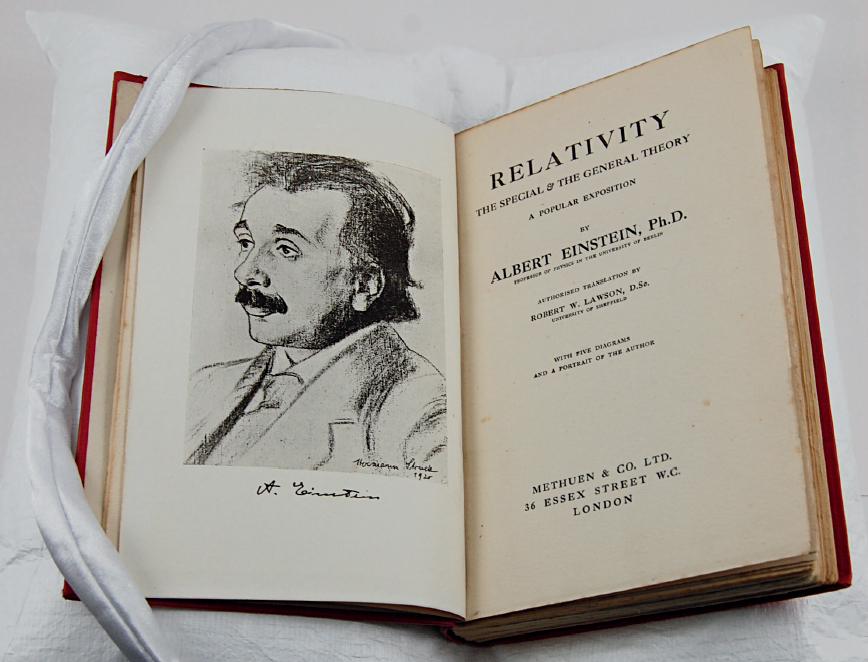

He later presented the two theories together in a book, Relativity: The Special and General Theory, which was first published in 1917. Within three years, it had run through fourteen German editions, totalling 65,000 copies. But it took more time for the gravity of Einstein’s revolutionary ideas to become widely accepted as law.

Relativity is a method for two people to agree on what they are seeing if one of them is moving. Einstein’s equivalence principle holds that gravity pulling in one direction is completely equivalent to an acceleration in the opposite direction. Thus, a rider on an elevator accelerating upwards feels like gravity is pushing them into the floor.

Einstein’s relativity theory introduced a new framework for all of physics, proposing new concepts of space and time, relativity of simultaneity, and kinetic and gravitational time dilation. Einstein posited that every time you measure an object’s speed, its momentum – or how it experiences time – will always be measured in relation to something else: it is relative. The speed of light remains the same no matter who measures it or how fast the person measuring it is going, and nothing can travel faster than the speed of light. Einstein not only pronounced his theory – he also said it was provable.

In November of 1919, he became an overnight celebrity throughout the world when a solar eclipse provided the first accepted confirmation of his theory of general relativity. Headlines everywhere hailed him as the greatest scientific genius since Isaac Newton.

The theory of special relativity was also confirmed in numerous other tests, and the physics community generally understood and accepted it by the 1920s. Special relativity rapidly became a significant and necessary tool for theorists and experimentalists in the new fields of atomic physics, nuclear physics and quantum mechanics.

The full significance of general relativity wasn’t as widely recognised until the 1960s, when it became central to such discoveries as quasars, microwave background radiation, pulsars, black hole candidates and Big Bang theories. Its practical applications have included the development of global positioning systems and high-precision time measurement.

Unlike most other scientific breakthroughs, general relativity was largely a product of Einstein’s unique thinking and not a further contribution to other work that was going on at that time. No one else was thinking of gravity as equivalent to acceleration, as a geometrical phenomenon, as a bending of time and space. Consequently, his surprising theory vastly expanded scientific knowledge and altered the course of history.

The first edition of 1916 (below) and the first English translation of 1920 (above). Along with quantum mechanics, Einstein’s theory of relativity is one of the key pillars of modern physics. His publication rewrote Newton’s physical laws and introduced a new way of understanding the universe.