All Quiet on the Western Front is a brutal account of the effects of war on young soldiers at the front. It has sold more than fifty million copies since its publication, but was one of the first books declared ‘decadent’ by the Nazis and burned in public bonfires in 1933.

When he turned eighteen in 1916, German-born Erich Maria Remarque (1898–1970) enlisted in the army and was posted to the Western Front in northern France. Much of All Quiet on the Western Front is autobiographical, and certainly based on firsthand experiences. It is narrated by its central character, Paul Bäumer, who enlists with several of his classmates at the age of nineteen.

The book describes life on the front line, and the often violent deaths, one by one, of Paul’s comrades. It is unflinching in its depiction of horrific injuries, and although Remarque insists in his preface that he is not making political points, his characters repeatedly question the nationalism that drives the conflict. The soldiers’ real enemies are not ‘the enemy’, but the men in power, far behind the lines of battle. Soldiers kill each other not out of any ideological purpose but purely to avoid being killed. One of the book’s key passages is the moment when Paul stabs a French infantryman for the first time in hand-to-hand combat. He bitterly regrets his instinctive action and nurses the man as he slowly dies. In another passage he is similarly sympathetic to ‘enemy’ Russian prisoners.

Traditional war novels glorified heroism and patriotism. Remarque presents the grim reality of modern warfare, where killing is made easier by machines – guns, tanks and airplanes. More than earlier wars, World War I dehumanised those who fought it, both by the means of killing and by the sheer scale of it.

All Quiet on the Western Front chronicles the soldiers’ emotional disconnection in the face of such slaughter. You might die at any moment, so you live only in the moment. ‘Goodbye’ becomes the hardest word. The men cut themselves off from family and friends, from memories of the past and from hope for the future. The only shreds of humanity that survive are the intense bonds between brothers in arms.

Remarque found that publishers were hesitant about printing his book, fearing that ten years after his country’s defeat in World War I, there would be little appetite for stirring up memories of it again. Instead, it was serialised in the Berlin daily newspaper the Vossische Zeitung in the last two months of 1928, where the response was encouraging enough to publish it in book form the following year. All Quiet on the Western Front was at once an international success, translated into more than twenty languages and selling two and a half million copies in the first eighteen months. An American film production of it was released as early as 1930 and was nominated for five Oscars and won three, including Best Picture and Best Director.

One of the most remarkable things about All Quiet on the Western Front is its success in countries such as America and Great Britain, which might not have been expected to sympathise with the traumas of enemy soldiers. Remarque’s masterpiece succeeded, and endures, because of its universal message: war is hell for all combatants, and at heart all men are brothers.

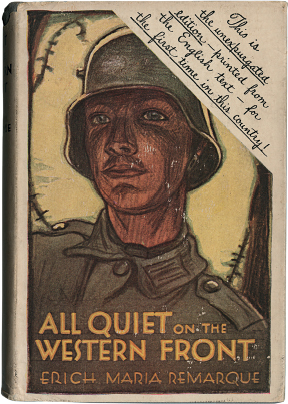

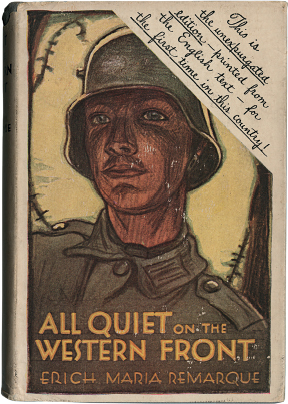

The first UK edition (above), published in 1929 by Putnam. The Grosset & Dunlap edition (opposite) was published in 1930 in New York. It is described as ‘unexpurgated’ because it included a scene of a battalion’s visit to a latrine that Little, Brown (the original US publisher) removed for fear of offending its readers.