The Doors of Perception

Aldous Huxley

(1954)

The Doors of Perception, which described a single hallucinogenic experience, went on to influence the rising drug culture of the 1950s and ‘60s. Huxley’s measured report of his first mescaline trip is lucid, detailed, and philosophical about the drug’s good and bad effects.

Aldous Huxley (1894–1963) settled in California in 1937 when he was already the successful author of the dystopian novel Brave New World. Even before he left his native England, he had shown an interest in the effects of mind-altering drugs, and in spirituality. In Brave New World the state keeps the people docile with a constant supply of a fictional drug called soma. The protagonist of his 1936 war novel Eyeless in Gaza turns to Eastern philosophy to ease his disillusionment with the world. Huxley, himself disillusioned by the path that he saw society following in the twentieth century, had turned to meditation at this time.

In 1952, Huxley’s attention was caught by the research of an English psychiatrist, Humphry Osmond. Osmond was experimenting with mescaline (the hallucinogenic component of the peyote cactus) as a treatment for schizophrenic patients at his Saskatchewan mental hospital. The two men corresponded, and Huxley volunteered to take mescaline experimentally in the presence of Osmond, in the hope of removing conscious barriers to his spiritual enlightenment.

Huxley may have had another motive for experimenting with hallucinogens. Following a childhood illness, his eyesight was so bad that he was at times almost completely blind. Was he hoping to receive a different kind of vision?

The experiment took place on May 3, 1953, in Huxley’s West Hollywood home. The Doors of Perception is the record of that day. The title is taken from William Blake’s 1793 book The Marriage of Heaven and Hell: ‘If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, Infinite.’

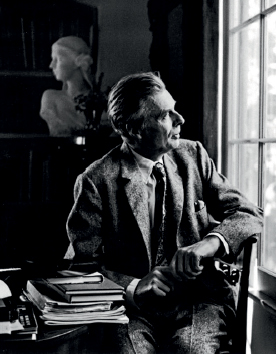

The first edition, with a dust jacket design by John Woodcock. Huxley (shown opposite) took his title from William Blake’s poem ‘The Marriage of Heaven and Hell’: ‘If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, Infinite. For man has closed himself up till he sees all things thro’ narrow chinks of his cavern.’

Huxley had a very visual response to the drug. A vase of flowers, for example, became ‘a miracle of naked existence’, while a book of famous paintings opened his eyes to abstract colour and pattern, even in figurative works. Towards the end of his trip, the garden chairs took on an intense reality that threatened, he felt, to drive him mad.

He concluded that although heightened perception should be possible without mescaline, nevertheless, it helps, and certainly works better than tobacco and alcohol. Mescaline, he wrote, did not make men violent – quite the opposite: they were brought to inaction because the experience was so vivid and gripping. He conceded that some users might have bad trips, and felt that at around eight hours its effects lasted inconveniently long. But on balance it offered a change in perception that was worth having.

Huxley, who had been critical of such drugs in Brave New World, was converted. He took mescaline several times a year for the rest of his life, and he took LSD for the first time a year after the publication of The Doors of Perception. Furthermore, he is said to have introduced Timothy Leary and Allen Ginsberg to the idea of experimenting with psychedelic drugs – indeed, he and Humphry Osmond invented the word ‘psychedelic’. Without such experimentation we might have missed out on the Beat poets, the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper, the Doors (named after the book), Woodstock and all the cultural legacies of the 1960s that are still felt today.