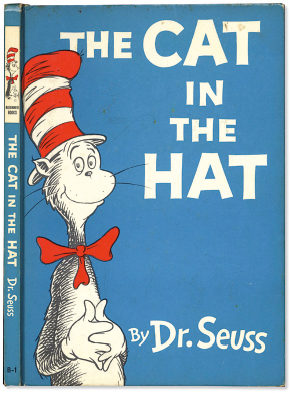

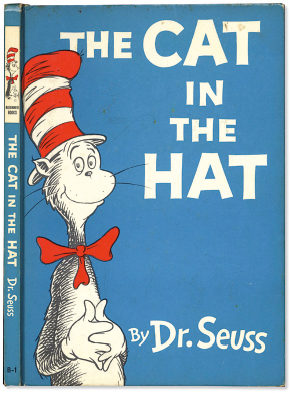

The Cat in the Hat

Dr. Seuss

(1957)

The book that broke the mould in young children’s literature. Setting out to write an alternative to ‘pallid primers with abnormally courteous, unnaturally clean boys and girls’, Dr. Seuss gave us a world of fun seen through children’s eyes.

Dr. Seuss (1904–91) was born Theodor Seuss Giesel, an American son of German immigrant stock. He adopted the title Dr. to please his parents, who had wanted him to study medicine, but his early career was as an illustrator of books, advertisements, and wartime propaganda. His first children’s book, And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street, was rejected by twenty publishers before getting into print in 1937.

Mulberry Street’s title and text contain the trademark rhythm and rhyme that would reach their zenith in The Cat in the Hat. The rhythm is anapaestic tetrameter – four units of two unstressed syllables and one stressed one – much used by epic poets such as Byron and Browning to convey a dramatic, galloping mood. Its breathless pace also lends itself well to comedy.

Seuss wrote The Cat in the Hat in response to 1950s criticisms of the inadequate reading primers available to children at the time. The Dick and Jane series had been in use since the 1930s, and their simplistic, moralistic stories were neither remotely entertaining for children nor effective in teaching them to read. Seuss would later declare that The Cat in the Hat ‘is the book I’m proudest of because it had something to do with the death of the Dick and Jane primers.’

Publisher William Spaulding gave Seuss a list of 348 words suitable for six- to seven-year-olds from which he should choose 225 with which to write a better primer. Frustrated by these limited options, Seuss decided that he would write a story about the first two words on the list that rhymed. They were, of course, ‘cat’ and ‘hat’. In the end he used 236 different words in the book.

The result was the irresistible tale of an anarchic cat in a red-and-white-striped top hat that arrives to brighten the lives of two children stuck at home on a rainy day. He brings giggle-inducing chaos and disorder to their afternoon; he juggles domestic items, including a rake and goldfish, and introduces Thing One and Thing Two, the children’s reckless alter egos, who fly kites in the corridors. But when the children’s laughter turns to anxiety about the mess they’ve made and the imminent return of their mother, he restores order and leaves.

The book has been analysed in absurd depth over the years. The disapproving goldfish, for example, has been seen as the joyless, puritanical streak in American culture, and the red-hatted cat and his red-romper-suited Things are the invasive anarchy of red communism in the McCarthyist United States of the 1950s. Today, we might see the cat as a nonconformist punk, twenty years ahead of his time.

Dr. Seuss certainly approved of him – his face is not unlike Seuss’s, and the sorrowful expression he wears when he has to tidy up seems to express Seuss’s own regret. The book has endured, and its simple rhythms and rhymes have proved effective in encouraging children to read for themselves. Above all, it is a testament to Seuss’s ability to see the world through children’s eyes, to understand more than Dick and Jane ever could what children find funny.

Theodor Giesel (Dr. Seuss), with an early edition of The Cat in the Hat – ‘It is the book I’m proudest of because it had something to do with the death of the Dick and Jane primers.’ It was published under the newly formed Beginner’s Books imprint of Random House, which aimed to provide books for children between the ages of three and nine.