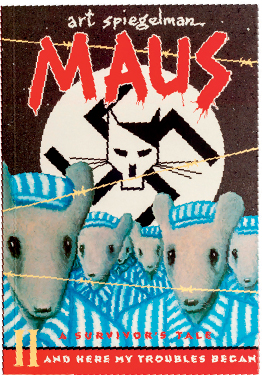

Using interviews with his father as a starting point, Spiegelman found a new way to write about the Holocaust, and with it the graphic novel came of age. This genre-defying book is now a modern masterpiece.

The term ‘graphic novel’ was coined in 1964, but cartoons and comic strips have been compiled into book form since the early nineteenth century. In the twentieth century, superhero stories and fantasy tales took the genre in new directions, thanks to the likes of Stan Lee, and from the 1970s Raymond Briggs drew more philosophical novels about the humdrum lives of his characters.

Maus, however, took the graphic novel to a new level. It has been subjected to serious academic debate about its form, its content, and its style. It captures real, horrific events in history by focusing largely on the painful memories of one man, portraying difficult intimacy and wholesale inhumanity with equal power. Its overriding theme is guilt.

Maus describes one Jewish Pole’s experience of the Nazi Holocaust. It is a true story. The man, who survived Auschwitz, is Art Spiegelman’s father, Vladek, and his memories are framed by modern scenes in which Spiegelman (born 1948) interviews his father in order to capture his wartime memories for inclusion in Maus. These interview scenes are further framed by a meta-narrative in which Spiegelman wrestles with how to use the material that he has gathered in the interviews.

Spiegelman explores guilt in several ways. There is the obvious but unfelt guilt of the Nazis who ran the concentration camps. Art’s relationship with his father is not an easy one, and Art feels guilty for not being a better son. He also feels guilt at not being able to do his father’s story justice. Vladek too bears some guilt, for having burned the invaluable wartime diaries of Art’s mother after she committed suicide in 1968 – something Art also feels responsible for.

Art and Vladek both experience survivor guilt – Vladek because so many of his fellow Jews died, and Art because his older brother was killed in the war, before Art was born. Art suffers further guilt about having had such an easy life compared to his parents and about how he should feel about the Holocaust, which happened before he was even alive.

Spiegelman presents the Jews in Maus as mice (‘maus’ is the German for ‘mouse’) and the Germans as cats – a reference to the Nazis’ intention to eradicate the Jews like vermin. The different species are a powerful metaphor for separations of class and race in Nazi Germany. Racism is perpetuated in one modern scene: Vladek, the victim of Nazi racism, is furious because Art picks up a black hitchhiker one day.

Spiegelman originally published Maus in magazine instalments between 1980 and 1991. In book form it first appeared in two parts, in 1987 and 1991. It has the literary depth of a classic novel, and the graphic skills of a master draughtsman, and there was much confusion about how to classify the book and where to shelve it in bookstores. It was art, biography, autobiography, history, memoir and comic book. The book industry only adopted the category ‘graphic novel’ in 2001, and when Spiegelman won a Pulitzer Prize for Maus in 1991, they avoided classification by giving it a ‘special award’. This special book, which has now been translated into more than thirty languages, continues to move and provoke.